Читать книгу Dutch Treats - William Woys Weaver - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

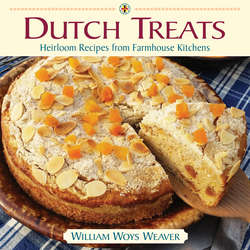

ONE FESTIVE BREADS Fescht Brode

ОглавлениеIf we reduced Pennsylvania Dutch farmhouse culture to one iconic dish, it would be sauerkraut without a question; yet eye-catching, delicious-tasting breads also define the traditional Pennsylvania Dutch table, with their remarkable range of festive shapes and flavors. During the colonial period, Pennsylvania became the breadbasket of the English colonies. The main growers of that wheat were the Pennsylvania Dutch. They measured their wealth in bushels of wheat, they paid bills with it, and their bread baking was legendary. Any farmhouse worthy of the name possessed a beehive bake oven in the yard not far from the kitchen door. It was the weekly task of the mistress of the household to bake bread, pies and cakes – often on a massive scale. Baking was generally undertaken on Fridays so that there would be plenty to eat for Sunday dinner. However, when the holidays drew near or a wedding loomed on the calendar, the baking frenzy went into high gear, usually with the help of relatives or friends from the neighborhood. The most traditional of these specialty items demanded their own shape, flavor and story. That is the subject of the chapter at hand.

The original Pennsylvania Dutch term for cake was Siesser Brod (sweetened bread), which in local parlance among the non-Dutch became “cake bread.” Siesser Brod implied that the Fordeeg (foundation dough) was bread dough, the very same used for making common loaf bread, except that the foundation dough was then elaborated with any number of additional ingredients, such as eggs, honey, sugar, spices, saffron or dried fruit. These dressed-up breads took many forms, perhaps the oldest and most classic being Schtrietzel, which was a loaf of bread shaped like a braid, or as some culinary historians would suggest, a head of grain. Regardless of the symbolic meaning, these were special occasion foods and some were only made once a year. Many did not contain much honey or sugar since they were meant to be toasted and eaten with jam – the classic spread being Quince Honey (Qwiddehunnich) as presented on page 11. One of the basic recipes in this category, which became a fixture of many Sunday dinners, is so-called Dutch Bread, in some respects a study in simplicity because it is not very rich in terms of ingredients. Our heirloom recipe was preserved by Anna Bertolet Hunter (1869-1946) of Reading, Pennsylvania. The Bertolets are one of the oldest and most distinguished Pennsylvania Dutch families in Berks County and have always been at the forefront when it comes to preserving local culture.

Aside from farmhouse baking, there are period records from before the Civil War of bakeries in large towns that specialized in festive breads like the New Year’s Pretzel, large gingerbread figures and Hutzelbrodt – since these breads require an oversized oven. In rural areas, this task sometimes fell to local taverns, which possessed the bake-oven capacity and turnover of customers to generate extra money from seasonal sales. It was also common for people in the neighborhood to pitch in to help the taverns during the busy holidays – and get paid with Christmas baked goods in return for the work.

One of the earliest historical recipes for Siesser Brod surfaced in the 1813 account book of Lebanon County furniture maker Peter Ranck (1770-1851), who must have acquired auxiliary training in baking. Ranck called his recipe Zuckerweck (sugar buns) because he shaped the bread into small rolls for Christmas or New Year’s. In short, the same foundation dough was used to make Dutch Cake (Pennsylvania Dutch Gugelhupf), New Year’s Boys, Lebanon Rusks and Christmas dinner rolls called “Kissing Buns” (Kimmichweck).

Gingerbread mold depicting New Year’s Pretzel, Schtrietzel and Kissing Buns

The kissing buns acquired their name because they consisted of two round buns baked side-by-side so that they would “kiss” and stick together – they were sent to the table in pairs as shown in the old gingerbread mold above.

Plain bread rolls made in the same shape with the best sort of wheat flour were called wedding rolls because they were expensive and were only served on high occasions of that nature – of course the kissing bread was also symbolic of the wedding couple and the work cut out for them on their honeymoon. The earliest known Pennsylvania Dutch image of these kissing buns appeared in a carving on the 1745 case clock of Lancaster bread baker Andreas Beyerle. Thus, while the written record in cookbooks may be skimpy, other types of evidence attest to the important place such festive breads once held in traditional Pennsylvania Dutch culture. For this chapter, I have selected several iconic breads representing the major calendar events in the year.