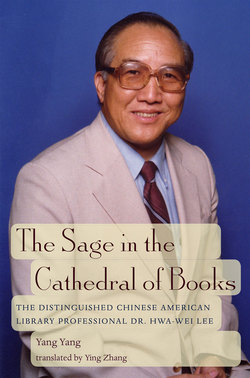

Читать книгу The Sage in the Cathedral of Books - Yang Sun Yang - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

The War Years in His Youth

One ship drives east, and another drives west,

With the self-same winds that blow;

’Tis the set of the sails, and not the gales,

Which tells us the way to go.

Like the winds of the sea are the ways of fate,

As we voyage along through life;

’Tis the set of the soul that decides its goal,

And not the calm or the strife.

—Ella Wheeler-Wilcox, “The Wind of Fate”

1

HWA-WEI’S ANCESTRAL home is Fuzhou, Fujian Province; however, he was born in Guangzhou on January 25, 1931. His father, Kan-Chun Lee, was then the governor of Shihui County in Guangdong Province. The third child in the family, Hwa-Wei had one brother, Hwa-Hsin, who was five years older; one sister, Hwa-Yu, who was three years older; three younger brothers; and one younger sister.

The year 1931, the Chinese Year of the Sheep, witnessed a turbulent rainy season in Southern China. The drenching rain seemed to have no intention of stopping or slowing down; instead, it kept expanding its coverage beginning in Guangzhou and moving further north. By May of that year, the rainstorms had already covered more than half the country. The water levels of several rivers, including the Pearl, Min, Yangtze, and Huaihe, rose rapidly. The fierce tides seemed to declare that this would be a disastrous year.

By June and July sixteen provinces were declared disaster areas, including Fujian, Guangdong, Guizhou, Hunan, Hubei, Jiangxi, Anhui, Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Henan, Liaoning, and Heilongjiang. Countless houses and fields across half of the nation were submerged in floodwaters. An article from Guo Wen Zhou Bao, a weekly newspaper from Tianjin, reported: “The current number of officially declared disaster provinces is sixteen. However, the actual number should be much more than sixteen, if we include the reports from various news sources. . . . The remaining provinces, such as Hebei and Shanxi, were also affected by considerable degrees of rainstorms and flood. It is likely that almost no province has been unaffected. This is truly a historical catastrophe.”

Three townships in Wuhan, with floodwaters ranging from three to thirty-two feet deep, were among the most seriously affected areas. Scattered buildings were like isolated islands in an ocean of muddy water. Having stayed in Wuhan for a few days to inspect the situation, the head of the Nationalist government, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek (Kai-Shek Chiang), acknowledged the severity of the flood in his Address to the People in the Disaster Areas: “The flood has covered a large part of the nation, south and north to the Yangtze River. The tragedy and severity of its damage is very rare throughout history . . . not only has it affected residents’ daily lives, but it also has threatened the welfare of the entire nation.”1

Facing such a peril, the Nationalist government in Nanjing lamented in its call for National Disaster Relief: “Look at the towering muddy water that is never draining away and at our vast cultural heritage in danger of being submerged. The deceased have been swallowed by fish, whereas the survivors have been suffering from the famine. What a misfortune to our nation! And what a catastrophe to our people!”

This flood, the biggest to date of the twentieth century in China, had affected so many provinces that the headcount of victims reached as high as 70 to 80 million, almost one-sixth of the national population. This serious inundation put the Nanjing government under tremendous pressure as millions of victims, overwhelmed with grief, lost their homes and sought refuge. Nevertheless, this was just the prelude to an even greater disaster.

September 18, 1931, witnessed a military conflict, the historic “9.18 Incident,” in northeast China between the Chinese Northeast Army and the Japanese Kwantung Army. Bold action by pro-war Japanese military forces, combined with the pacifist policy of the Nationalist government, led to a bloodless occupation by the Japanese army of the city of Shenyang and then of all three northeast provinces, Liaoning, Jilin, and Heilongjiang. In March 1932, the Japanese invaders established the puppet state of Manchukuo with its capitol in Changchun, Jilin Province. This was followed by an aggressive expansion into other regions of China. September 18 thus became known as the “Day of National Humiliation” to the Chinese people.

Conquering China had been on Japan’s national strategic agenda ever since the Meiji Restoration of the late nineteenth century. In June 1927, Prime Minister Tanaka Giyichi submitted a proposal to the emperor of Japan that said: “Conquering of China must begin with conquering Manchuria and Mongolia, and conquering the world must start with conquering China.” This greedy desire and ambition for continuous expansion inevitably ended in the vicious invasion of China, forcing the country into the flames of war and the suffering Chinese people into deeper misery.

Hwa-Wei was doomed to spend his childhood years in the chaos of wars and natural disasters.

2

Hwa-Wei’s great-grandfather, Shun-Ching Lee, was a successful businessman in Fuzhou, capable of providing his children and grandchildren with opportunities for a good education. Hwa-Wei’s grandfather, Tzu-Ho Lee, was a Xiucai, a scholar who had passed the imperial examination of the Qing dynasty, and made his living by teaching in his hometown. His career path, education, was later followed by Hwa-Wei’s father, Kan-Chun Lee (whose former name was Sheng-Shu Lee), and by Hwa-Wei himself, making three generations of the Lee family professional educators.

Fuzhou, named after Mt. Fu to its north, is located south of the Min River, with warm and rainy weather typical of the south. Driving from the city center to the East Sea takes only about an hour.

For two thousand years, the city had always enjoyed a certain degree of monopoly and autonomy, given the geographic advantage of being far away from the central governments. Further, as a “blessed place,” as the name “Fuzhou” implies, this ancient city, with hills behind and a sea in front, had rarely suffered from calamities caused by natural disasters and human intervention.

Fuzhou also has a poetic nickname—Rongcheng, which literally means Banyan City. Banyan trees could be seen everywhere in the city since the Northern Song dynasty (960–1120). With its continuously growing prop roots, one banyan tree can spread out, over hundreds of years, to form a far-reaching and very dense thicket, resembling from afar a lovely hill covered with green foliage. Ancient memories of this city are likely hidden in those thick tangles of banyan roots and trunks.

Unlike the natives of many other inland cities, Fuzhou people are primarily the mixed descendants of migrants from central China and local natives, with minimal regional ethnicities among them. During the Song dynasty, one thousand years ago, Fuzhou was already a well-known open-trading port on the east coast. It was, indeed, from the two harbors in Fuzhou, Mawei and Changle, the famous Admiral Zheng He (He Zheng) embarked on his seven naval expeditions between 1405 and 1433.

Fuzhou later became one of the five designated trade ports in the Sino-British Treaty of Nanjing, following China’s defeat in the Opium War. As a result, countless foreign diplomats, businessmen, missionaries, and adventurers flocked to the southern city. Its residents, therefore, were among the earliest Chinese people to have direct encounters with westerners and western civilization. Meanwhile, along with the introduction of Wuyi tea to the western world, the Fuzhouese started to sail across the ocean and to extend their sojourns abroad.

In 1931, Hwa Wei and his family visited his parents’ home in Fuzhou. Returning on that visit were (front, left to right): two cousins; six-month-old Hwa-Wei; his sister, Hwa-Yu; and his brother, Hwa-Hsin (Min).

In 1932, Hwa-Wei’s family moved to Nanjing. Shown are (left to right): Hwa-Wei’s brother, Hwa-Hsin (Min); his sister, Hwa-Yu; his father, Kan-Chun Lee; and Hwa-Wei.

Hwa-Wei and his mother, Hsiao-Hui Wang, in Nanjing, 1932.

Whereas the ocean brought a yearning for a wandering life to the Fuzhouese, the surrounding mountain terrain cultivated conservative and traditional virtues among them, along with an open-minded nature. This is why overseas Fuzhouese descendants still preserve their traditions of family and homeland patriotism, their persistent ingrained attitudes, as well as their industry and thrift, regardless of their circumstances.

The natural and cultural environment in Fuzhou nourished the older generations of Hwa-Wei’s family. Hwa-Wei’s father, then Sheng-Shu Lee, received his early education in church schools. Later, he went to Yenching University to study theology and education under the guidance of John Leighton Stuart. Originally a missionary in China, Mr. Stuart later switched his focus to academia and became the founding president of Yenching University. His philosophy of academic freedom and openness was carried on through generations, making Yenching a unique institution of higher learning in China.2 As a young student, one from a historic city far to the south, Sheng-Shu Lee was greatly influenced by Mr. Stuart and his philosophy.

Having earned his master’s degree from Yenching University, Sheng-Shu went back to the south and worked as an associate professor and then as a professor at Fujian Christian University. He later served as the principal of Fujian Christian Normal School until he joined the Nationalist Revolutionary Army in 1928 and changed his name to Kan-Chun Lee in accordance with his new career identity.

From a noble family in Fuzhou, Hwa-Wei’s mother, Hsiao-Hui Wang, had two siblings, a younger brother and a younger sister. All three received a good education from church colleges. Hsiao-Hui and her sister, Hsiao-Chu Wang, graduated from Hua-Nan College of Arts and Sciences in Fuzhou. Both were devout Christians.

Hsiao-Hui’s brother, Tiao-Hsin Wang, was a chemistry professor, department chair, and then dean of the School of Science at Fujian Christian University (FCU). In 1948, he came to the United States to further his studies, returning to China in 1949, soon after the Communist Party took over the country, to continue his teaching and research at FCU. He was once the acting university president and also a board member of the Chinese Chemical Society. Unfortunately, he lost his life in the Cultural Revolution due largely to his religious affiliation and Western connection.

Hsiao-Chu Wang (Her English name is Phyllis Wang.), Hwa-Wei’s maternal aunt, went to Beijing to study education at the Graduate School of Yenching University after her graduation from Hua-Nan College. She later relocated from Beijing to Guangzhou, where she worked as the head of cataloging, chief of general affairs, deputy director, and director at the Lingnan University Library. Hsiao-Chu came to the United States in 1948 on a scholarship provided by the board of Christian Higher Education in China and received her Master of Library Science (MLS) degree from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign (UIUC), two years later. Because of the political situation in China and the closing of her university after 1949, she decided to settle in the United States and worked in several libraries, including the Health Sciences Library at the University of Pittsburgh.

Hwa-Wei could not remember if he ever visited Fuzhou with his parents and siblings in his childhood. However, in a later visit to Fuzhou in search of his family roots, during his first trip back to the mainland since 1949, he spoke with his uncle’s wife, who insisted that the family—Hwa-Wei, his parents, older brother, and sister—had made a trip back home when Hwa-Wei was still a toddler. In spite of a blank spot in his memory involving that visit, he, interestingly enough, still had a lingering memory of the slightly sweet and astringent taste of the locally grown green olives.

On Hwa-Wei’s father’s side, there is only one known relative, his aunt, a medical doctor. Hwa-Wei met her only once in Chongqing and, unfortunately, lost contact with her after the family moved to Taiwan.

3

Living in a turbulent era of domestic turmoil and foreign invasion, Hwa-Wei’s father, young Kan-Chun Lee, aspired to dedicate his life to his country. He was once a devout Christian and worked as the secretary general of the Christian Education Association in Fujian. However, his perception of Christianity gradually changed due to the influence of the popular “May Fourth Movement.” He grew to believe that the spread of Christianity in China was a disguised form of political and cultural invasion by the Western colonial powers. Some aggressive Chinese students and intellectuals at that time even labeled foreign missionaries and their approaches as “mission and missile.”3

He eventually chose to leave his religious work and changed his name from Sheng-Shu, “Holy Gospeller,” to Kan-Chun, “Joining the Army,” indicating his transformed view of the world and his determination for a career change from academia to the military. In August 1928, he resigned from his position as the principal of Fujian Christian Normal School and joined the Nationalist Revolutionary Army. Kan-Chun started with the title of publicity department chief (a lieutenant-colonel ranking) in the Eleventh National Revolutionary Army, and was promoted one year later to director of the Political Training Academy (a colonel ranking) in the Sixty-First Division of the army. He was the governor of Shihui County, Guangdong Province, from 1930 to 1932, then transferred in 1932 to Nanjing, where he became the secretary and, later, chief of the Statistics Department of the Ministry of Interior, while also serving as a lecturer at the Political Training Institute of the National Military Commission. The entire family, including Hwa-Wei, also relocated to Nanjing with Kan-Chun.

Hwa-Wei in Nanjing, 1935

Hwa-Wei and his siblings, Hwa-Ming, Hwa-Hsin, Hwa-Yu, and Hwa-Nin, in Nanjing, 1936. Hwa-Wei is seated fourth from the left.

Hwa-Wei’s father, Kan-Chung Lee, and mother, Hsiao-Hui Wang, in Nanjing.

Hwa-Wei’s paternal grandmother.

Hwa-Wei’s paternal grandfather, Tzu-Ho Lee.

Hwa-Wei’s maternal grandfather.

Hwa-Wei’s maternal grandmother.

July 1937 witnessed the Lugouqiao (Lugou Bridge) Incident, which instigated the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War. It took only five months for the menacing Imperial Japanese Army to conquer Nanjing, the capital of the Republic of China, followed by the two-month-long historic Nanjing Massacre. The atrocities committed there by the Japanese occupiers between December 13, 1937, and February 1938 included the barbaric killing of almost three hundred thousand civilians and the destruction of one-third of the city. The Yangtze River was dyed red with the fresh blood of the victims. The notorious “Rape of Nanjing” by the brutal Japanese aggressors turned the Chinese ancient capital of six dynasties into a ghost town and a massive graveyard.

Luckily, the Lee family had already left Nanjing for Guilin of the then Guangxi Province, as Kan-Chun Lee had been hired by two regional military leaders there, General Li Tsung-Jen (Zongren Li) and General Pai Chung-Hsi (Chongxi Bai), to be the education officer in the Provincial Cadre Training Corps. The two generals highly regarded Kan-Chun’s work experience as the governor of Sihui County, Guangdong.

Located in the northeast of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, Guilin has a revered reputation among the Chinese—“Guilin’s scenery is the best among all under the heavens”—due to its amazing landscape with intertwined lofty mountains and flowing rivers. Guilin’s famous scenic spots include the Duxiu Mountain Peak at the center of the city, Elephant Trunk Hill on the south, Seven Star Cave and Crescent Hill on the east, and Wind Cave and Folded Brocade Hill on the north.

As the Japanese invasion expanded rapidly in China, the situation in Guangxi worsened. Heavily loaded with work both day and night, Kan-Chun had little time to take care of his family. To ensure their safety, he decided to send his wife and six children to Haiphong in Vietnam, allowing them to escape the daily bombing from the Japanese airplanes. Kan-Chun and a contingent of subordinates escorted his loved ones on this journey all the way from Guilin, Nanning, and Liuzhou to Longzhou. There they crossed the border from the south of Longzhou into Hanoi and finally arrived at Haiphong.

Hwa-Wei remembers the long journey as a harsh and endless one. Along some sections of the road, they were able to take buses; on the others, only horseback riding or walking was allowed. Five out of the six children, except Hwa-Hsin, were too young to make the trip on their own. The two younger brothers, Hwa-Ming and Hwa-Nin, had to sit in large baskets, one in the front and the other in the back, of a shoulder pole carried by one of their father’s subordinates. The youngest, Hwa-Tsun, had to be held or carried in a cloth sling. Seven-year-old Hwa-Wei was transported on a horse. He was afraid of falling from the horse, as rough and rugged mountain paths made the bumping and jerking horseback ride quite unstable. The rider used a rope to tie Hwa-Wei to the front of him, warning Hwa-Wei not to move. It was arranged for Hwa-Wei’s pregnant mother to travel in a sedan chair carried by the men taking turns.

It is not quite clear to Hwa-Wei why his father chose Haiphong as the sanctuary for the family. It could have been that some of his father’s friends were living there. As the largest harbor in northern Vietnam, Haiphong was then a French colony with arrogant police officers everywhere.

After Kan-Chun returned to Guilin, Hsiao-Hui Wang and her six children temporarily settled in Haiphong. She took good care of everything in their simply furnished rental home. Several months later, Hwa-Chou, the youngest sister, came into the world. Hwa-Wei’s mother was truly an extraordinary woman, one able to manage household affairs very well, while looking after her seven children, including one newborn, in a foreign country. On the few later occasions when the family’s refugee experience in Haiphong was mentioned, Hsiao-Hui always expressed thanks that all of her seven children were able to survive, something which seemed like quite a miracle during that time. She always felt happy and grateful that her family was able to escape from the war and live a simple life in a foreign land.4

Eighteen months later, his father arranged for the family to move back to Guilin. The trip home was somewhat easier, as all the children were better able to manage by themselves. Hwa-Chou, the youngest sister, was held in her mother’s arms all the way back. When the family checked in at the immigration office in China, the mother and children were all registered as returning overseas Chinese. For that reason Hwa-Wei later went to the National Number Two High School for Overseas Chinese for his junior high education.

4

Sharing the same goal of fighting against the invading Japanese troops, General Li Tsung-Jen’s Guixi armed forces reconciled with Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek’s central government and formed a temporary alliance. As the general commander of the Fifth War Area, General Li Tsung-Jen, collaborating with General Pai Chung-Hsi, directed the Battle of Taierzhuang. Due to careful deployment of the joint troops, Taierzhuang became a major victory for the Chinese, the first of the Nationalist Alliance against the Japanese army.

This victory boosted the reputation of the Guixi military. From Guangxi, a region home to impoverished but valiant people, Guixi warriors had already become well known as an “iron army” as early as the time of the Northern Expedition. Guixi forces were involved in numerous famous and extremely tough battles against the Japanese invaders. General Joseph W. Stilwell, the chief of staff to Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek, once marveled at the quality of this army, calling the Guixi soldiers the best warriors in the world.

A very subtle and complicated relationship of mutual exploitation and mutual vigilance existed between Li Tsung-Jen’s Guixi army and Chiang Kai-Shek’s central government. To get Li Tsung-Jen under control, Chiang Kai-Shek “promoted” Li in September 1943 from general commander of the Fifth War Region to chief commander of the Hanzhong Field Headquarters of the National Military Commission, a wartime senior authority between the central government and the Combined First, Fifth, and Tenth War Regions. This was a promotion in name only because, although it increased the number of war regions under Lee’s supervision, it decreased his military power, as the Field Headquarters was, indeed, a paper agency.

After the Sino-Japanese war ended, Li was transferred in August 1945 to the Beijing Field Headquarters with the same rank.5 Hwa-Wei’s father, Kan-Chun Lee, already a lieutenant general, became Li’s confidential advisor. Kan-Chun followed General Commander Li to Beijing where the family moved into the Qinzheng (diligence to government affairs) Hall in Zhongnanhai. The headquarters was located in the Juren (be benevolent) Hall. Originally built in the Ming dynasty and renovated in the Qing dynasty, Qinzheng Hall had once served as the offices of visiting emperors during their stays in Zhongnanhai.

Located on the west side of the Forbidden City, Zhongnanhai consists of two parts, Zhonghai (Central Sea) and Nanhai (South Sea), and was once, along with Beihai (North Sea), referred to as “Three Seas” in Beijing. With its winding streams, Zhongnanhai has a landscape differing from that of the solemn and respectful Forbidden City. All the emperors since the Liao (916–1125) and Jin (1115–1234) dynasties favored Zhongnanhai and invested large amounts in its expansion and renovation. Zhongnanhai became an imperial garden and political center in the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), serving as the emperors’ summer resort and governance place. After the Revolution of 1911, it became one of the essential meeting venues of the Beiyang Warlord Government.

Hwa-Wei did not move with his family to Zhongnanhai. He stayed at the First Municipal Middle School in Nanjing to continue junior high school. What he knew of his family’s life in Zhongnanhai, he learned from his brothers. According to them, the layout of Qinzheng Hall was rather complicated, comprising some thirty rooms of different sizes, including an anteroom, a hallway, a reception room, central and west-wing living rooms, and a dining room, as well as a very imposing home office. The home office, used mainly by Hwa-Wei’s father, had a gigantic rosewood desk in which his father’s documents were kept.6

Qinzheng Hall actually continued its political function in the post-1949 era until it was demolished in the 1970s. There Mao Zedong (Zedong Mao) would often hold his diplomatic meetings with heads of foreign countries and other dignitaries.

Under the U.S. mediation, Mao Zedong, accompanied by then U.S. Ambassador Patrick J. Hurley, flew to Chongqing in August 1945 for peace talks between the Nationalists and the Communists. An agreement to end the military conflict was reached and recorded in the meeting memo. However, under that peaceful and harmonious surface simmered the never-ending troop deployment. Before long, the Communist armed forces, having been enhanced and fortified in the northeast, launched large-scale warfare in the areas of Changchun and Siping against the Nationalist troops.

By the spring of 1946, the Chinese Civil War had spread all over northern China. The peace talk agreement eventually became invalid. The unfortunate Chinese civilians, who had been allowed no time to celebrate the end of World War II, were soon drawn into this dreadful civil war, a life or death combat between the Nationalists and the Communists. Early in 1947, the Lee family was compelled to move back to Guilin from Beijing.

There was no way for Hwa-Wei’s father and older brother to stay away from the increasingly brutal war; both were inevitably involved. The winter of 1948 saw a reversal between the two parties as the People’s Liberation Army won three decisive battles, Liaoshen, Pingjin, and Huaihai, over the Nationalist Army. Having sustained several successive defeats on the battlefield, Chiang’s popularity dropped dramatically.

Meanwhile, a nationwide economic breakdown became the deathblow to Chiang’s government, bringing the Communist Party to the center stage of history.7 In order to make the new round of peace talks more effective, Chiang resigned from his presidency on January 21, 1949, appointing Li Tsung-Jen the acting president, with a primary mission of easing the tension and suing for peace. However, Li’s proposal of a joint rule of China with the Nationalists to the south of the Yangtze River and the Communists to the north was immediately rejected by both the Communist government and by Chiang Kai-Shek.

Three months later in April 1949, Mao’s army succeeded in breaking through the defensive line along the Yangtze River. Thus, the Nanjing Nationalist Government instantly lost its power on mainland China. On October 1, 1949, Mao Zedong proclaimed the birth of the People’s Republic of China in Beijing.

As the Communist army approached Guangzhou, Li Tsung-Jen had no choice but to flee the country. He flew to Chongqing on October 13, then left Chongqing for Hong Kong on November 20, after he was diagnosed with a bleeding gastroduodenal ulcer. On December 5, Li left Hong Kong for New York City to seek medical treatment, accompanied by his wife and two sons.8

Li’s interim government was dissolved thereafter. Chiang’s Nationalist Government eventually withdrew to Taipei on December 7 after several short stays in Guangzhou, Chongqing, and Chengdu. Mainland China and Taiwan have been separated by the Taiwan Strait ever since Chiang moved to his final base.

5

Having worked for the Guixi division for many years, Kan-Chun Lee failed to get himself and his family entrance tickets to Taiwan. Facing the reality that General Li Tsung-Jen was hardly able to protect himself, Hwa-Wei’s father had no other choice but to resign himself to his fate.

While the Lee family was still trapped in Guilin, the oldest son, Min Lee (whose former name was Hwa-Hsin Lee), had already withdrawn to Taiwan as an officer in the Nationalist Air Force. As an elite soldier in Chiang’s army, Min was allowed to bring his family members to Taiwan. At the end of September 1949, only a few days before the founding of the new China, Min arranged a military transport plane from Taiwan to Guilin, rushed the entire family aboard, and flew back to Taiwan. Thus, at a critical moment in history, all nine members of the Lee family dramatically departed China for Taiwan onboard a special plane, thanks to Min’s arrangement.

All the family members hurried onto the military transport plane. The inadequate safety devices and little radar guidance combined with the bad weather put the family at great risk during their escape. Because of Taiwan’s high mountains, the plane, in order to land safely in the dense low clouds, had to gradually descend over the ocean before proceeding to land at the military airport in Central Taiwan. Due to these circumstances, Min and his copilot asked everyone to look out the windows and let them know immediately upon sighting the ocean so that they could control the aircraft below the low and heavy clouds.

It was Hwa-Wei’s first flight in an air force aircraft, and he was very excited. Hwa-Wei and his other siblings did not feel scared at all. Instead, they all saw the endeavor as quite interesting. All started to yell as soon as they saw the dark blue sea through the windows. The plane started low-altitude flying above the ocean. Thanks to Min’s superb piloting skills, they made a safe landing at the Hsinchu Air Base in Taiwan.

Four days after the Lee family escaped from Guilin, the entire Guangxi Province was taken over by the People’s Liberation Army. Back then, Hwa-Wei did not realize that the next opportunity for him to return to mainland China would be thirty-three years later in 1982!

With only a few hours’ notice and given limited cargo space, the Lee family was not able to take many of their belongings with them on the flight. They had nothing to call their own upon arrival in Taiwan.

Owing to years of political infighting between Chiang and Li, and Li’s being away in the United States, Li’s former subordinates who had managed to leave the mainland and relocate in Taiwan were unable to escape being oppressed and squeezed out of government positions. Because of his close Guixi connection, it was obvious that Kan-Chun Lee would have no chance to continue his political career in Taiwan. In addition, he, himself, had lost interest in working as a government official after experiencing so many ups and downs in politics.

Having been enlightened by reality, Kan-Chun, now in his fifties, decided to return to teaching, his previous profession. Teaching was truly an easy job for Kan-Chun due to his fluency in English and his background as a former student of John L. Stuart at Yenching University. It did not take him long to land a job teaching the English language at Taichung College of Agriculture, which later changed its name to National Taiwan Chung-Hsing University. A popular lecturer among students, he soon was promoted to the rank of full professor. This teaching job did not make the family wealthy, but neither were they poor. Compared with many other families retreating from the mainland to Taiwan, the Lees were indeed blessed and, after a short time, settled in Taichung.

Kan-Chun was an exceedingly brilliant professor. He was highly regarded and well supported by his university president. He was visited frequently by junior faculty members looking for his guidance. The recognition and respect he earned from his teaching career brought Kan-Chun true happiness. Therefore, he often told his children not to pursue a political career, citing his own experience and the vain outcome of his previous involvement in politics. In his later years, Kan-Chun felt working in academia was a more worthwhile pursuit because it brought a noble and virtuous life.

The necessity of Hwa-Wei’s father returning to teaching worked out well for him; the latter half of his life became a more cheerful and comfortable time. Kan-Chun’s teaching career lasted until he was almost in his seventies.

After his retirement, Kan-Chun returned to a religious life, using his previously earned missionary credentials, and became a guest minister at a Methodist church in Taichung. Kan-Chun’s church service was volunteer-based, as churches in Taiwan were inadequately funded, unlike their American counterparts. Kan-Chun Lee lived a long life and passed away at the age of eighty-nine. He was buried in a graveyard in Taichung with his wife, Hsiao-Hui Wang, who died one year later, at age ninety.

6

Hwa-Wei’s father had a proficiency in English; after the family relocated to Taiwan, he was able to use that skill to make a living for his family. Later, Hwa-Wei was even more impressed with his father’s English when his father helped him edit and polish his application documents for American graduate schools.

Among the seven children in his family, Hwa-Wei’s personality most closely resembles that of his father; he is also the child most heavily influenced by him. Nevertheless, the hardships his father had suffered were probably greater than anything Hwa-Wei has had to experience. Kan-Chun continually endured wars and political turmoil during the first half of his life. He underwent changes in his life path from his original devotion to Christianity to his dedication to the Nationalist Revolution, as a follower of General Li Tsung-Jen. The perils of those decades of military service were like treading on thin ice. Fortunately, he was able to settle down with a stable teaching job and do missionary work in his later years.

Kan-Chun took the bad with the good and honored the code of brotherhood. His limited income could barely provide the essential expenses of his big family, even under his wife’s thrifty management. On many occasions when the family was unable to make ends meet at the end of the month, Hwa-Wei’s mother had to trade the jewelry from her dowry to feed the family, or his father had to borrow money from one of his eleven blood brothers whose financial situation was slightly better. He had no alternative but to seek help from his friends for the sake of his family. Hwa-Wei could feel the helplessness and agony of his father; this only increased Hwa-Wei’s respect for him.

The blood brothers of his father were primarily Fujianese, known for their strong ties with each other. Hwa-Wei met two or three of them, including I-Wu Ho, who had once served as the secretary general of the Taiwan Legislature, the vice chairman of the Commission of Overseas Chinese Affairs, and the president of the board of Cathay United Commercial Bank. Ho was a great help to the Lee family and provided kind support to Hwa-Wei and his siblings with their plans to study abroad.

Hwa-Wei’s father was a family man with only a few personal hobbies, playing mahjong, smoking, and drinking with friends. His mother was a perfect housewife who took good care of all seven children. Among the many kinds of love, the most selfless love is the devotion of parents to their children. The adults who are closest to a child during childhood usually shape that child’s life. The personality and character traits of Hwa-Wei’s parents had a far-reaching impact on their children. The harmonious and relaxing family atmosphere that they created has benefited Hwa-Wei and his siblings their entire lives.

Because Hwa-Wei left home at the young age of twelve for schooling, his mother was always very kind and loving to him whenever he came home during school recess. During his youth, Hwa-Wei suffered from chronic allergic sinus infections and had to undergo surgeries each year for nasal polyp removal. When providing him with meals more nutritional than those he got in school, his mother always made him his favorite dish: five-spice red-cooked stewed pork shoulder. Hwa-Wei has always treasured those memories of his mother and still remembers the aromas of the food she prepared for him.

Notes

1. Hongyec Guo, “The Nationwide Flooding of 1931,” Yan Huang Cun Qiu, no.6 (2006).

2. Qing Li, The Not Lonely Past. Jing-Po Fu: Accompanying John Leighton Stuart for 4 Years (Hong Kong: Joint Publishing, 2009).

3. Stacey Bieler, A History of American-Educated Chinese Students, trans. Yan Zhang (Hong Kong: Joint Publishing, 2010).

4. Hong Lu, “Extending time and space in searching and offering—the life of Dr. Hwa-Wei Lee, Director of Ohio University Libraries,” Mei Hua Wen Xue (The Literati), no. 25 (January/February 1999): 24–43.

5. De-Gang Tan, Memoirs of Li Tsung-Jen, 1st ed. (Guilin: Guangxi Normal University Press, 2005).

6. The Bloodstained Red Sky: In Memory of the Martyrs of the Aircraft 815 of the Air Force 34th Black Bats Squadron. (Taiwan: published by family members of the 815 Aircraft, 1993).

7. Len-Yu Huang, Reading the Dairy of Chiang Kai-Shek from the Historical Perspective, (Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Jiu Zhou Press, 2008).

8. De-Gang Tan, Memoirs of Li Tsung-Jen.