Читать книгу The Sage in the Cathedral of Books - Yang Sun Yang - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 3

National Taiwan Normal University

Hope is the thing with feathers

That perches in the soul

And sings the tune without words

And never stops at all.

—Emily Dickinson

1

THE ISLAND of Taiwan became the only remaining territory of Chiang Kai-Shek after 1949. The post-war division of Korea and ensuing Korean War resulted in a flow of military and economic aid from the United States. With that aid and the natural water barrier of the Taiwan Strait, Chiang was able to resettle the Nationalist government on the island and thus establish China as a dual governance structure.

The largest city on this island, Taipei, features four major east- and westbound arterial roads: Chung-Hsiao Road, meaning loyalty and filial piety; Jen-Ai Road, meaning benevolence; Hsin-Yi Road, meaning faithfulness; and Ho-Ping Road, meaning peace. Meanwhile, many streets and alleys in Taipei are named after mainland cities and provinces. Even the layout of these streets and alleys resembles their geographic locations in mainland China, making Taipei seem a miniature facsimile of China. In addition, there are also thoroughfares with names—such as Siwei, meaning four social guidelines; and Bade, meaning eight virtues—chosen from literary allusions to primary Confucian classics.

When Hwa-Wei first came to Taipei, bicycles and rickshaws were the primary means of transportation in this simple and tranquil city; automobiles were not popular at all. Traffic signals meant nothing to pedestrians crossing the street.

With the resettlement in Taiwan, Hwa-Wei started as a twelfth-grade transfer student at Provincial Taichung First High School. After graduation, he passed the entrance examination and was admitted to the Provincial Taiwan Teachers College (renamed later as the National Taiwan Normal University), which was, back then, one of only a few institutions of higher education in Taiwan.

During the fifty years of Japanese occupation from 1895 to 1945, local students were kept from receiving education in political science and economics. They were only allowed to study in subject areas such as education, history, literature, and medicine. The restriction remained until after the Nationalist government moved to Taiwan and instituted an educational reform. Before long, the National Taiwan University (NTU) and the National Taiwan Normal University (NTNU) rose as the two flagship universities on the island. The latter assumed a unique position in educating generations of future educators in Taiwan.

With its main campus located on the northwest side of Taipei, NTNU was founded in 1946 at the site of the former Taiwan Provincial College, which had originally been established by Taiwan’s Japanese government in 1922. Many buildings on campus, featuring neo-Gothic and Gothic architectural styles, were built during the era of Japanese occupation. NTNU is just a few miles away from NTU, the other famous university established in Taiwan since the 1950s, one well known then for its academic freedom. As an institution for teachers’ education, NTNU was more restrictive, known for its practice of the school motto: “Sincerity, Integrity, Diligence, and Thrift.”

When the Nationalist government retreated to Taiwan in 1949, they took many influential Chinese intellectuals with them, including Ssu-Nien Fu and Shih-Chiu Liang. Fu was the president of NTU until December 1950 when he died of heart disease. The president of NTNU was Chen Liu, a renowned educator. Liu was able to recruit some distinguished faculty members from Beijing Normal University (BNU) to move with him to Taiwan in 1949, owing largely to his good relationship with BNU. These faculty members were resettled either at NTU or NTNU. Among those were Shih-Chiu Liang (English), Ming Kao (Chinese), and Liang-Kong Yang (Education).

A number of famous scholars from NTU, including Shih Hu and Mu Ch’ien, also gave lectures at NTNU. Mei-Chi Hu, Ch’ien’s wife, was a classmate of Hwa-Wei at NTNU in the Department of Education. Professor Mu Ch’ien and his wife, despite the large difference between their ages, had a happy marriage. In his later years, Professor Ch’ien lost his eyesight, and his wife, Mei-Chi Hu, worked as his assistant, becoming essential to her husband’s scholarly work in history and philosophy. Many of the later publications of Professor Ch’ien were the result of his dictation, recorded and edited by his wife.

Interested in civil engineering, Hwa-Wei originally applied for NTU’s College of Engineering. At that time there was a unified college entrance examination on the same day for all colleges in Taiwan, except NTNU. To improve his chance of college admission, Hwa-Wei also participated in NTNU’s entrance exam, using it as a backup. It turned out that Hwa-Wei’s math score for the unified examination was not good enough to get him into his dream school to study engineering. His NTNU test, however, was successful. Thus, Hwa-Wei ended up in the Department of Education at NTNU. Due to his father’s influence, Hwa-Wei was interested in education and even dreamed about becoming a secondary-school principal.

There were no more than three thousand faculty and students in Hwa-Wei’s first year at NTNU. In addition to free boarding and tuition, each student also received an annual set of uniforms and a regular monthly allowance. Hwa-Wei was happy to see the reduced financial burden for his parents and felt more comfortable about not being able to go to NTU for civil engineering.

NTNU was known for its strong faculty and vigorous academic requirements. It was NTNU where Hwa-Wei started his continuous and systematic education. To Hwa-Wei, the four years at NTNU have had a tremendous impact on him and his career.

At NTNU, Hwa-Wei, thin and tan, was quiet, but he was polite and got along well with others. Not being a bookworm, he was not a very good student, however. Hwa-Wei devoted many of his free hours to extracurricular activities and joined a variety of organizations, but none based on any specialty or particular strength.

One such organization was the school’s drama troupe. The ineloquent and ordinary-looking Hwa-Wei was very active as the group’s stage manager. He became an indispensable troupe member, busy with making room reservations, preparing costumes, and managing props and stage sets. As time grew closer to a play’s opening, he became even more engaged. For example, when the sound of a storm was needed during a performance, Hwa-Wei would lead the effort of providing the live sound backstage using pots and pans.

At the time, the NTNU drama troupe was very famous among the universities in Taipei. As one of the backbones in the troupe, Hwa-Wei was highly capable, always putting the backstage area in perfect order with minimal effort. People enjoyed working with him and admired his hard work and dependability.

At the NTNU drama troupe, Hwa-Wei had two good friends, Ching-Jui Pai and Hsing Lee, who both later became influential film directors, with a huge impact on Taiwan’s movie industry. Ching-Jui was an art major and started school the same year as Hwa-Wei; Hsing, two years ahead of Hwa-Wei, was also a student in the Education Department. Knowing Hwa-Wei was working backstage always made the two friends feel relieved while performing onstage. They knew that Hwa-Wei was reliable and dedicated; he never made mistakes in backstage management when in charge of lighting, sound effects, and scene changes.

Large in voice and body, but with an old head on a pair of young shoulders, Hsing Lee was the head of the drama troupe and took care of the others just like an older brother. In contrast, Ching-Jui Pai, originally from northeast China and nicknamed Little Pai, was small and ordinary looking. His personality was humorous, straightforward, and unrestrained. Despite the differences in temperament, the three friends made a good team and often planned activities together. Having no money for drinking, or even for tea, did not prevent them from one or two sumptuous meals, usually a bowl of beef noodles, a well-known night snack in Taiwan.

Hsing Lee became famous in the 1960s for his film Beautiful Duckling and has been regarded since then as the representative of “healthy realism” and as the godfather of the Taiwan film industry. Ching-Jui Pai also gained fame in the Taiwan film industry for Lonely Seventeen, after returning from Italy, where he studied film and media. Combining the two famous directors’ family names, their peers jointly nicknamed them Lee Pai, one of the acclaimed ancient Chinese poets.

The two film directors stayed very close friends after their college years. Hsing Lee always gave a hand to Ching-Jui Pai, who had bad luck with his personal life and career, and passed away at the age of sixty-six. Hsing Lee is still very active in Taiwan’s film industry as the president of the Taiwan Film Association. Over the years, Hsing Lee has been a member of the selection committee for the Golden Horse Awards—Taiwan’s equivalent to the Academy Awards—and he himself was honored with the Golden Horse Life Achievement Award in 1995.

Despite their different life paths, Hwa-Wei and the two film directors maintained a good relationship. Every time Hwa-Wei visited Taiwan, the three friends always gathered together for drinking and talking, as if they were back in their college days.

2

NTNU produced many distinguished alumni during the 1950s. Chin-Chu Shih, former deputy minister of education of Taiwan, was a student of good character and fine scholarship from Hwa-Wei’s class. Other classmates of Hwa-Wei, such as Chen-Tsou Wu, Hong-Hsiang Liu, Hsien-Kai Shen, and Wen-Chu Yin, became renowned university professors or high school principals. Another classmate, Ming-Hui Kao, after having earned his doctorate in the United States, returned to Taiwan and later served as a vice-general secretary of the Nationalist Party.

Other classmates whose superior leadership skills impressed Hwa-Wei are Chih-Shan Chang and Ping-Yu Yan. Chang and Yan, both university presidents in their later years, were leaders of the China Youth National Salvation Corps (CYNSC), which in 2000 changed to its current name of China Youth Corps. During their college years, they teamed up with Hwa-Wei in organizing summer combat training camps for college and high school students in Taiwan. Hwa-Wei still remembers his active years in CYNSC, serving as the captain of the Summer Youth Naval Battle Camp his first year, and the chief of the Lanyu (Orchid) Island Expedition Team during his second year.

As a college student, Hwa-Wei stayed busy with extracurricular activities. He was one of the leading members of the Education Departmental Student Association. In addition to serving in NTNU’s drama troupe, Hwa-Wei was involved in student publications, including a campus wall newspaper and a student literary magazine.

The wall newspaper was composed of a large sheet of poster paper on which articles and essays were written using Chinese brushes. While the design of the newspaper was created by Hwa-Wei, the news articles and essays were drafted by Hui Chen, a talented Chinese literature major. The two were also responsible for the student literary magazine, which gained quite a reputation on campus.

For the magazine, Hui served as the editor and Hwa-Wei assumed typing, publishing, and distribution responsibilities. Unfortunately, the brilliant editor Hui was not able to employ his full literary talent after he moved to the United States. He was diagnosed with melancholia, a mental disorder characterized by severe depression, guilt, hopelessness, and withdrawal. He eventually died in a tragic suicide, jumping from the forty-fifth floor of the Rockefeller Center in New York City.

Presumably owing to his gentle disposition, Hwa-Wei was constantly sought after by his friends to help with various events and activities. He never turned down invitations or requests and always enjoyed participating. Thus, his college life turned out to be much busier than that of many others. His bony body was like a gigantic energy field with unfailing vitality. As a sports lover, Hwa-Wei succeeded in basketball, as well as in track and field events. He was once the champion of NTNU’s eight-hundred-meter run. This was an unbelievable sports achievement for Hwa-Wei, considering his physical condition.

Throughout his four years of college, Hwa-Wei often went to the Student Guidance and Counseling Services to obtain permission slips allowing his absence from classes. He would then hand-deliver these to his professors. Each permission slip would read something like: “Your student, Hwa-Wei Lee, will have to miss the class [on a given date] due to a scheduling conflict with a [specified] school event he will attend; please give him permission.”

Many professors back then ranked academic work over extracurricular activities and thus would see a student’s involvement in non-course-related programs as a sign he was neglecting his studies. Every time Hwa-Wei gave an absence permission slip to a professor, the professor would say nothing, but give a stern look. Some professors would never fail to remind Hwa-Wei of an approaching finals week, saying something like: “Hwa-Wei Lee, you’d better put extracurricular activities aside and focus on your study. Otherwise, I don’t think you will be able to pass my class, as you’ve missed so many sessions.”

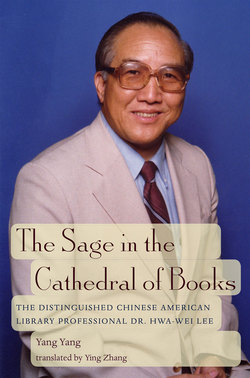

Hwa-Wei at the Provincial Taiwan Teachers College in Taipei, 1950. In 1954 the college was renamed the National Taiwan Normal University.

With regret, Hwa-Wei would sincerely reply, “Thank you, Professor! Please trust me. I will study hard to make up.” Luckily, Hwa-Wei was always able to pass examinations and even received better grades than his professors had expected owing to his strengths in logic, analysis, and writing, as well as his all-night cramming right before an exam.

For every exam, Hwa-Wei would usually stay up the whole night in the classroom reviewing textbooks and notes. The next morning, he would put the textbooks and notes aside, wash his face with cold water, and get ready for the exam. Hwa-Wei was only able to gain short-term memory, though, from the last-minute preparation for the exam, as everything acquired from the overnight study would soon be forgotten. His skill at cramming just before his exams won him quite a reputation in the Education Department. His professors were also surprised and started to be fond of this student who was shy when speaking but passionate about after-school programs.

It was Hwa-Wei’s personality that kept him active behind the scenes of many off-school programs. It took him a while to realize the value of those extracurricular activities in shaping his leadership skills including motivating and encouraging others; cultivating fellowship and partnership; and planning thoroughly, then implementing effectively. The development of those skills proved an unexpected windfall from his college years.

Unconsciously, Hwa-Wei had already started preparing for his future through exploiting his potential. He had no idea why he was always able to get people together and accomplish many difficult tasks. Looking back to his college years, Hwa-Wei finally came to understand that it was indeed that leadership potential he had developed in college that contributed to his career success in the United States, earning him promotions faster than his colleagues—starting with the University of Pittsburgh Library. This was a special achievement considering he was a foreign student and a non-native English speaker.

Hwa-Wei (front row, right) with fellow classmates in the Department of Education.

Hwa-Wei (front row, far right), who was good in sports, won first place in the eight-hundred-meter race.

Hwa-Wei accepts a trophy from the president of the university.

Despite the richness of its extracurricular activities, NTNU, a teachers’ education institution, was rather strict on discipline. It was mandatory that girls return to their dorms before 9:00 p.m., and boys no later than 11:00 p.m. However, that regulation was not followed strictly by boys who, fed watery and flavorless food from the school cafeterias, were starving at night.

In those hours, the overpowering smell of beef noodle soup, blasting from the other side of the campus wall, became truly alluring and irresistible. Hwa-Wei and his friends often could not help but climb over the wall to savor late-night food and then climb back. The boys enjoyed their rebellious act, and even felt more excited, when they were caught right inside the wall by Chong-Le Wang, head of the student life unit of Guidance and Counseling Services, and had to run fast to escape. As the champion of the eight-hundred-meter run, Hwa-Wei had never been captured and was thus ranked by Wang among the naughtiest of the students.

An easy-going person, Hwa-Wei never had conflicts with others—with only one exception. He had a classmate who constantly abused the others. Although these classmates felt indignant, no one dared to say a word back. One day, having reached the end of his endurance, Hwa-Wei stood up and criticized the bully. Infuriated by the bony Hwa-Wei, to whom he never would have paid attention, the bully immediately picked up an ink bottle and cast it over Hwa-Wei, leaving ink splashed all over his body. Giving his shirt a shake, Hwa-Wei threw a quick and unexpected blow to the bully’s face. The poor guy, never having anticipated that hard lick from the good-tempered Hwa-Wei, staggered there with a bloody face. Hwa-Wei’s fist was truly relentless, knocking out one of the guy’s front teeth, which cut his own hand, a wound that later formed a scar.

That was the only fight in Hwa-Wei’s entire life. Hwa-Wei, himself, was no less shocked than the bullying classmate. Stunned by his own burst of energy, Hwa-Wei was also struck dumb. He had never imagined that his single blow would immediately control the opponent.

The consequence was bad. The university administration punished Hwa-Wei—regardless of his reason for the fight—with probation, two major and two minor demerits, and all the medical expenses of the wounded classmate. Luckily, Hwa-Wei was able to counterbalance the demerits using an equivalent amount of merits earned from his extracurricular activities.

What bothered Hwa-Wei most was the medical expense. One reason for his decision to go to Normal University to study education was to help with his family’s tight budget, as the school provided free tuition. How could he then let his parents pay for the medical charge? If not from his parents, where could he acquire funds as an impoverished student? It became a real headache for Hwa-Wei. Knowing his difficulty, the majority of his classmates, who were on Hwa-Wei’s side for his just behavior, pooled their pocket money for him. The medical expense was finally scraped together after Hwa-Wei added two more tutoring jobs.

3

The 1950s saw a constant growing tension between the two sides of the Taiwan Strait following the conclusion of the Chinese civil war. The entire island was armed and ready to counterattack the mainland at any time and hoped to receive more support from the United States when the fight commenced. Although it was a pressing desire of Chiang Kai-Shek to retake the mainland, he was not quite confident of his military strength. After all, restarting the war at that time would be a life-or-death choice. If it failed, Chiang could lose Taiwan, his last resort in the world. Having weighed the pros and cons, Chiang decided not to take further action.

Back then in Taiwan, military training was mandatory in colleges. Student dorms, supervised by full-time drillmasters, were treated as military barracks with everything, including the bed, in order. To students like Hwa-Wei, whose family income was on the low end, one big advantage of this military training was free uniforms and shoes. Under the military system, students had to stay on campus during part of their summer school breaks to undergo basic military training in drill and marksmanship.

One educational outcome was the increasingly high patriotic sentiment across the campus concerning the Republic of China. Many times the institution sent the school’s drama troupe and its dance club to the offshore island of Kinmen to perform for soldiers staying on the front line. Other students also helped illiterate soldiers, who comprised a large portion of the troops, in writing letters to their families.

Hwa-Wei remembers the entrenchment in Kinmen as rather complex and concealed, spreading in all directions while also being hardly visible from the outside. He once entered an auditorium that was built just inside an excavated mountain, truly an eye-opening experience to Hwa-Wei, who had been interested in civil engineering. He was amazed at the creativity of its engineers.

Actually, Kinmen is a very small island lacking favorable geography for shelters and concealments. The best way for the Nationalist army to build structures for hidden military facilities was to excavate inside mountains. A cave airbase could be used easily for aircraft taking off and landing when its gate was opened. The Nationalist army was quite confident in the sheltering structure. One slogan stated that the Communist army would be defeated right on the beach, if they dared to come. The Communist army did not attack Kinmen in the end. Hwa-Wei wonders what those military facilities look like today as the relations between the two sides have greatly improved.

In Taiwan, every adult man had an obligation to serve in the army. The duration of service as a soldier had been two years for a new high school graduate and thirteen months for a fresh college graduate at a reserve officer rank. After that, one had to go back to the service one month each year for a consecutive five-year term. This conscription system is still proving effective.

After graduating from NTNU in 1954, Hwa-Wei received his reserve officer training at the Army Officers Academy for six months and at the Political Cadre School for another seven months. The Army Officers Academy was located at Kaohsiung, a port city in southern Taiwan. The first six months there featured strict and intensive Initial-Entry Training (IET) for all new reserve officers regardless of their subject background. The training included all basic military combat skills. The reservists also participated in actual military maneuvers using real guns and bullets, and they were exposed to dangers as if they were authentic soldiers in true battles. It was rumored that there were indeed accidental injuries and deaths.

Immediately following the six-month IET came specialized training, determined by a reserve officer’s college major. For instance, an engineering graduate was most likely to be sent to the Artillery School, whereas an education major, like Hwa-Wei, was sent to the Political Cadre School, established to train future political and ideological instructors.

In the Communist army system, every company or higher unit has a designated political and ideological instructor. The Nationalist army also adopted a similar structure during the Chiang Ching-Kuo (Ching-Kuo Chiang) era, primarily due to Chiang’s Soviet background. Compared to his father, Chiang Kai-Shek, Chiang Ching-Kuo did a better job of connecting with the general public and accomplished many reforms that earned him nationwide acclaim and ultimately stabilized the rule of the Nationalist Party.

Prior to his college graduation, Hwa-Wei had already thought about his near future and made four specific plans. These included becoming a high school principal, getting assigned to a teaching job, studying abroad, and pursuing a graduate-level education. For each of the four plans, he needed to prepare for either a qualification test or an entrance exam.

Hwa-Wei’s original career plan was to become a high school principal, which required a candidate to pass an advanced civil service examination. To succeed at his second plan he needed to pass the government’s employment qualification test for job placement.

In 1953, Hwa-Wei (front) participated in summer military training, and was the head of the Naval Combat Team.

While in training, Hwa-Wei participated in naval combat exercises, 1953.

In 1953, Hwa-Wei successfully completed his naval combat training.

His third plan, to continue his effort to study abroad, was proving difficult: Hwa-Wei failed three times in earlier English-language proficiency tests for foreign studies. He seemed to have no choice but to keep trying, as his aunt in the United States, Phyllis Hsiao-Chu Wang, was trying to help him earn admission to a graduate program in education at the University of Pittsburgh with, possibly, a tuition scholarship. Meanwhile, it was not a bad idea to have an alternative plan for further education just in case his efforts in preparing to study abroad were in vain.

This led to his fourth choice: to take the entrance exam for graduate school in Taiwan. The entrance exam was very competitive. For instance, only five new students each year were admitted to NTNU’s Department of Education. Indeed, Hwa-Wei took the fourth choice most seriously and gave it the largest amount of time in preparation during his spare time and during military training.

The strict and rigid military training provided no opportunities for Hwa-Wei to spend time and effort in extracurricular activities as he had done in college. Thus, Hwa-Wei was able, fortunately, to concentrate on exam/test preparations. He buried himself in studying every evening in the classroom during regular self-study hours (from 7:00 to 9:30 p.m.). That proved to be effective because he passed all four tests and exams soon after the completion of his ROTC training.

Among his four goals, passing the entrance exam for graduate studies at NTNU was the most difficult. Admission was truly meant for top students, as reflected by the limited student enrollment quota. Hwa-Wei had to work very hard for a much-improved performance on his college academic scores. On his written test, his scores were ideal, the fifth in rank, which qualified him for the next round of oral exams.

The oral exam committee was composed of three faculty members: Prof. Kang-Chen Sun, department chair of Education; Prof. Pei-Lin Tien, dean of the Education College; and Prof. Pang-Cheng Sun. Hwa-Wei was extremely nervous in front of the three well-respected scholars.

Dean Tien started the exam saying, “Hwa-Wei Lee, you have done a good job in the written exam. However, you know we only need five new students. And we want top students who will commit their time to serious research, which is quite different from undergraduate education in this regard. Are you sure you want to head toward that direction instead of spending time in extracurricular activities?”

Hwa-Wei quickly responded, “Professor Tien, you are right. I did immerse myself too much in extracurricular activities. I will definitely focus on academic work if I am admitted.” Likely, Dean Tien and the other two committee members were touched by Hwa Wei’s sincere attitude, or impressed by the young man’s much-improved performance in the written test, because Hwa-Wei was admitted.

Hwa-Wei (third row, fourth from left) participated in the university-wide student visit to the military base on Kinmen Island.

Hwa-Wei (second row, second from right) graduated from NTNU, March 1954.

After graduation, Hwa-Wei’s (second row, sixth from left) first job was dean of students at the Affiliated Experimental Elementary School of the Provincial Taipei Teachers College.

Upon completion of his reserve officer training, Hwa-Wei soon started his first job as the dean of students at the Affiliated Experimental Elementary School of the Provincial Taipei Teachers College. Hwa-Wei actually got the job by chance.

Normally a newly graduated NTNU student was required to start with a one-year internship before becoming a high school teacher. The principal of the elementary school was Ta-Shih Tan. Principal Tan came to the chair of the Department of Education at NTNU, seeking his help in recruiting a college graduate from the department to fill the position of dean of students. Despite his disappointment with Hwa-Wei’s academic performance, the chair was impressed by this student’s ability in organizing extracurricular activities, and thus recommended Hwa-Wei to Tan as the best candidate for the position. Tan liked this modest, gentle, and quiet young man at first sight. The job offer thus came at once.

One year later, President Chen Liu recalled Hwa-Wei back to NTNU, initially as a teaching assistant. But he was soon assigned to work at the Extracurricular Activity Unit of the Student Guidance and Counseling Services overseeing student organizations. This was again a windfall to Hwa-Wei due to his strength in extracurricular activities.

Working with student organizations was a perfect fit for Hwa-Wei. He was enjoying the happiness of being an organizer and a team player, putting his accumulated experience and ideas to use. Hwa-Wei honored President Liu’s five equally important principles in educating students: moral development, intellectual growth, physical education, social activity, and aesthetic appreciation. He followed those five principles during his four years at NTNU, a practice that turned out to be beneficial throughout his life.

4

Soon after he was admitted to the NTNU graduate school, his U.S. visa application went through. That was truly his lucky year. Two good friends of his, who were used to having better college grades than him, were surpassed by Hwa-Wei, ranking sixth and seventh, respectively, in the entrance written exam for graduate school. The two friends, although aggrieved, felt somehow thankful, as they were outscored by their friend and not by a stranger. They were disappointed, however, when Hwa-Wei took the quota and then gave it up to study abroad. His two poor friends had to wait another year to fulfill their graduate school dream. Constantly berated by his two best friends, Hwa-Wei had no other choice but to treat them with meals by way of apology.

Originally, Hwa-Wei’s desire to study abroad was not that strong, as he had already been admitted to the graduate school of NTNU, making him feel closer to his dream profession of being a high school principal. And he was not very interested in going to the United States, a foreign country on the other side of the world, far away from his home. Rather, it was his parents and aunt who kept pushing him to pursue an advanced degree in an American university. The other reason for his initial reluctance to leave Taiwan for the United States had to do with his family’s financial status. Hwa-Wei needed to raise enough money for his plane ticket and the required affidavit of financial support, things his father was unable to afford. He knew that the road ahead to study abroad would not be an easy one. Hwa-Wei actually hoped that his visa application would not be granted so that he could have a legitimate reason to stay in Taiwan.

During that time, a large percentage of Taiwanese students who came to the States were from science and engineering backgrounds. Those students were more likely to be funded by American universities and thus had a higher success rate for a visa application. In contrast, very few humanities and social sciences students ended up on this path, as they seldom were able to receive fellowships, and their families, in most cases, could not afford the high costs of studying abroad.

Hwa-Wei, with help from his aunt, Phyllis Hsiao-Chu Wang, luckily was offered a tuition waiver from the School of Education at the University of Pittsburgh. This eased his visa application. After asking a few simple questions in English, the immigration officer, blinking his blue eyes, said to Hwa-Wei in an exaggeratedly slow speed, “You are welcome to America.”

It was just Hwa-Wei’s luck that a better and brighter future had come to him. But to achieve that better and brighter future, he would have to work harder and face tougher challenges.

It was time for Hwa-Wei to say goodbye to the dean of the graduate school saying, “Sorry, sir—I did not expect that I could pass the English test for foreign studies. This is quite an opportunity for me. Please allow me to withdraw from the school.”

Hwa-Wei promised the dean that he would study hard in the United States and come back to serve the university with a finished doctorate. The dean was very pleased, thinking that Hwa-Wei would soon be the first international student in the U.S. from his class. He simply wished him the best.

Hwa-Wei’s professors and friends at NTNU were all happy for him. But for Hwa-Wei, going to the U.S. for graduate school created not just financial stress but also psychological pressure. He could feel the sincere expectations and hopes of his professors and friends at NTNU. How would he ever “have face” to return to Taiwan if his studying-abroad endeavor failed? With this concern in mind, Hwa-Wei made up his mind to strive forward!

Subsidized by the government, Hwa-Wei had received four years of free college education at NTNU. But the government subsidy was conditional and required a beneficiary student to serve in the education field for at least five years after college graduation—before receiving his diploma.

Hwa-Wei felt guilty about his lack of service length, knowing that he had worked for only two years. Eventually, NTNU made an exception in his case and mailed his diploma to him. Attached with the diploma was a note stating that the original requirement for educational service in Taiwan had been waived because of his continued service record in the American higher education system and the graduate degree in education that he had received from the University of Pittsburgh.

Hwa-Wei’s service in the field of education has far exceeded his original commitment to NTNU. However, Hwa-Wei feels grateful for his college’s magnanimity and flexibility in ultimately awarding him a bachelor’s degree in education. He is also thankful to NTNU for his four years of rewarding experience, the impact of which on his life has proven more immeasurable than the diploma itself.