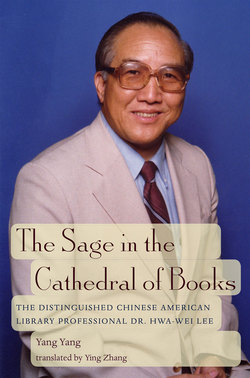

Читать книгу The Sage in the Cathedral of Books - Yang Sun Yang - Страница 20

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 4

Min Unafraid to Die

Please look at me in my eyes and honestly tell me

—is there a true victor in war?

—Ying-Tai Lung, Big River, Big Sea—Untold Stories of 1949

1

HIS WARTIME experiences during his childhood and adolescent years, especially during the Sino-Japanese War, have had a huge impact on Hwa-Wei. The city of Guilin is well known for its incredibly beautiful limestone mountains and rock formations in various shapes and sizes all along the Li River. There are many natural caves, large and small. Because of its geographical and strategic importance, Guilin was a target for Japanese bombers when Hwa-Wei and his parents and siblings lived there. They had to go with other civilians to one of the nearby mountain caves. Every time the air raid siren blared, frantic and frightened civilians dashed into caves. This kind of helpless response even got a humorous nickname, “Pao Jingbao,” which literally means siren-running. Because China had only a weak air force at the time, Japan had absolute air supremacy, and Japanese aircraft were free to come and go, just like frenzied devils. They usually flew so low that the pilots’ faces could be spotted.

After “siren-running,” Hwa-Wei and his family often had to pass by dead bodies to go back home. One time, his mother—holding Hwa-Wei’s hand—unwarily stepped on a corpse right after they walked out of a cave. Hwa-Wei was instantly frightened. A bolt of fear went through his body; he felt as if he were hit with an electric shock. That tragic death scene left a deep impression on young Hwa-Wei.

To flee from Japanese air bombings, civilians often left home at dawn for cave shelters in a nearby area carrying precooked or dried food. Outside the crowded caves, loud booms could be heard from time to time, sounds of constant explosions overhead. The caves and surrounding land trembled every time the booms sounded. Mixed with the explosions were continual whining and an ear-piercing siren.

Time passed slowly. Fear and despair seemed to be more torturous than death. Refugees dared not go back to their homes until dark. Often there would be no home left when they returned. The Japanese invaders seemingly did not want to skip a single decent house; they never neglected throwing a firebomb to burn one down. A nice street in the morning could be damaged beyond recognition by evening. Houses were burned to ruins, leaving broken structures and walls covered in smoke. On roadsides shabbily dressed refugees stood, wailing for their loss. The tragic scenes would make passersby sob. The war, blamed for so much tragic loss of lives and property, was tremendously painful, fearful, and hateful to the Chinese.

Like most Chinese youth at that time, Hwa-Wei’s older brother, Hwa-Hsin Lee, had made up his mind to join the Chinese air force to fight against the Japanese. In early 1940, the American Volunteer Group (AVG), formed and headed by General Claire L. Chennault under the endorsement of President Roosevelt and the U.S. government, came to China to help in combating the Japanese aggressor. Better known as the Flying Tigers, AVG originally was comprised of some one hundred young pilots and over three hundred mechanics and nonmilitary professionals. The headquarters of the Flying Tigers was located in Kunming of Yunnan Province, and their training base was set up in Burma. This Sino-U.S. Joint Air Force entered the Sino-Japanese war in early 1941.1

Having fought side by side with the Chinese Nationalist Air Force, the Flying Tigers shot down countless Japanese warplanes, helping the Chinese air force gain back air supremacy. The Chinese people who lived through the war have always been thankful to the Flying Tigers and its legendary military achievement. Hwa-Hsin was one of them. It was then that he decided to go to the Youth Air Force Academy.

In 1939, General Pai Chung-Hsi, deputy chief of staff of the Nationalist Military Commission, proposed the founding of the Youth Air Force Academy in order to train more pilots. Having received its name in early 1940, the academy selected—through strict physical and academic tests—primary and junior high school graduates between the ages of twelve and fifteen.

Students admitted to the academy were taught a variety of classes in aviation in addition to the general junior and senior high school courses. The academy placed special emphasis on good nutrition and physical education. Students, after their graduation from the academy, were sent directly to the Air Force Officers School for pilot training.2

According to Shih-Cheng Lou’s memoir, We Are the Anti-Japanese Air Force Reserves, the Youth Air Force Academy had eight recruitment centers in late 1940. These recruitment centers were in Chengdu, Chongqin, Guiyang, Kunming, Guilin, Zhijiang, Hengyang, and Nanzheng. There were nearly two thousand primary and junior high school graduates admitted to the academy in six groups. Hwa-Hsin was admitted in 1943 as a second-year senior high school student.

Similar to the general junior and senior high schools in content and length of education, the Youth Air Force Academy had, however, a different focus in curriculum. Students were given comprehensive Boy Scout training in the first three junior high years, and regular military training, aviation theory, and simulator instruction during the later three senior high years. Only those who were able to pass both the aviation-knowledge test and the physical examination could move up to the Air Force Officers School to receive real flight training. Those who met the standard of aviation knowledge, but failed in the physical examination, were sent either to the Air Force Mechanics School or the Air Force Communication School for further training. The Youth Air Force Academy was, in a way, a preparatory school for a variety of air force personnel.

Having graduated from the Youth Air Force Academy, Hwa-Hsin advanced to the Air Force Officers School in the fall of 1944. It was at that time he changed his name to Min Lee, as a statement of his commitment, following the example set by his father. The meaning of Min is described in the Chinese Classic of History (Shujing) as Min bu wei si, meaning intrepid and unafraid of death.

Taking the new given name of Min was Hwa-Hsin’s particular and determined way of declaring his pledge of fighting to the death against the Japanese invaders as an air force officer. A family archive photo captured the young and proud Min with his fellow cadets at their training base in India. On the gate behind these young airmen, a Chinese banner proclaims this motto: “Don’t enter this gate if you fear to die; and find another path if your goal is for promotion and wealth.” From the very beginning, Min knew his commitment to become a professional air force pilot meant he could not be afraid to die for his country.

Min graduated from the twenty-third class of the U.S. Air Training Command, completing his advanced pilot training at Barksdale Field, Louisiana, December 10, 1946. His officer training had started with a three-month-long program in Kunming; he was then sent to the training base in India. His years at the Air Command and Staff College were spent at Goodfellow Air Force Base in San Angelo, Texas.

Regretfully for Min, it was too late for him to join the fight against the Japanese upon his return from the United States at the end of 1946, as World War II was already over, and the Japanese invaders had already surrendered in disgrace. Min was sent off to northeast China to be stationed there. His first combat mission turned out to be—after the outbreak of the civil war on May 21, 1947—to fight against the Chinese Communist army, a goal counter to his original objective for joining the air force. At that point, his dream and destiny were taken by history to an unforeseeable end.

Min was an outstanding air force officer. Already a major at the age of twenty-nine, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel at thirty-one. Throughout his thirteen-year military career, he participated in many significant battles. Owing to his distinctive military performance, Min was the first student from his class to be promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel.

For a time after the Nationalist Government retreated from mainland China, the United States drifted away from an alliance with Chiang’s government. The estrangement did not last long. Soon after the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, the U.S. government realized its lack of intelligence information about the Peoples’ Republic of China and started to work on rebuilding the bilateral relationship with Taiwan. Two years later, a joint effort was made between Taiwan’s Air Force Combat Department and Western Enterprises, Inc., a CIA-affiliated company, to establish a Special Mission Unit. A mutual agreement was reached for the U.S. to equip the unit with B-17 bombers, which Chiang’s air force pilots would fly over the mainland on reconnaissance missions. Information gathered during these missions was shared by those two parties. Western Enterprises, Inc., was housed in an ash-gray, western-style building on 102 East Avenue, Hsinchu 102, Taiwan.

After the Korean War, Communist China became the potential enemy of the United States. In 1955, the headquarters of the U.S. Pacific Air Forces signed an agreement with the Taiwan Air Force Intelligence Department on an Electronic Countermeasure Mission (ECM), under which the Eighth Air Force Battalion located at the Hsinchu Air Base was sent off to conduct electronic reconnaissance.

As this mission proved effective, authority over future missions was transferred to Western Enterprises, Inc., the following year by order of the CIA. The Special Mission Unit was regrouped under the Air Force Intelligence Department and changed its name in 1957 to the Technical Research Group, formally known as the Thirty-fourth Squadron. A more popular name of this group was the Black Bat Squadron, as almost all the surveillance missions were conducted in China during the night. The squadron’s emblem featured seven stars beneath a black bat with its wings outstretched. Owing to his outstanding piloting skills and bravery, Min was assigned to the squadron in early 1958. His assignment was top secret, unknown even to Min’s parents and siblings.

As the leading aircraft of the Thirty-fourth Squadron, the American B-17 bombers, known as Flying Fortresses during World War II, were four-engine, heavy bombers of potent, long-range and high-load capacity. Under its core mission, intelligence gathering, the squadron’s bombers were modified to be reconnaissance aircrafts with original armaments removed and replaced by high-precision, electronic detection devices. The re-equipped (R) B-17 had no combat capacity at all and could board a maximum of fourteen crew members.3

To aid in the defense of China from the Japanese invasion, Hwa-Wei’s brother, Min (Hwa-Hsin), joined the Chinese air force. He received his training in both India and in the United States.

Min Lee completed his advanced pilot training at Barksdale Field U.S. Air Training Command in Louisiana, December 10, 1946.

The task of intelligence gathering was formidable for the squadron members who flew these RB-17s, usually leaving Hsinchu Air Base around 4:00 p.m. and entering the mainland’s air space after dusk. Flight duration varied from time to time and could last more than ten hours for each flight. Relying on the most advanced electronic detection devices and superior piloting skills, Black Bat Squadron crews were able to fly as low as one hundred to two hundred meters—the minimum safe-altitude zone—in the dark. In some cases, a crew had to break out of the safety zone and fly the aircraft as low as thirty meters off the ground in order to avoid radar detection.

On the other side of the Taiwan Strait, the Communist air force received a counter-reconnaissance order from Mao Zedong attached with a special award to whomever shot down a reconnaissance aircraft from Taiwan. Under the order, a network of anti-aircraft guns and searchlights were deployed in strategic locations waiting for planes, their targets, to fly over. This increased the risk to the Black Bat Squadron’s RB-17 bombers and their crews. Every mission was a battle against death. General Kuang-Yue Ko, former vice chief of the air force of Taiwan, said: “Each mission was targeted by more than ten missiles, more than ten attacks by fighter planes, and more than ten attacks of artillery fire.”4

Min, a highly skilled pilot, had been able to return safely every time from his mainland air expeditions for two years until his final trip on May 29, 1959. That day, two hours after returning from one reconnaissance mission, Min received an order to back up a sick pilot on the next trip. Hsiao-Po Meng, Hwa-Wei’s sister-in-law, recalled that it was a hazy day, which made her a bit worried.

Min comforted his wife by saying, “It is actually safer to fly through haze. This will be my last trip this month. And I shall be able to take a good break upon returning tomorrow.” Prior to the assignment, Min had taken out his military uniform with full medals from his suitcase and polished his leather shoes because May 31, just two days away, would be a big day to him as a professional airman. On that day Chiang Ching-Kuo was scheduled to pay a visit to the Hsinchu Air Base and offer his praise and encouragement in person to the squadron members.

On May 29, 1959, Taiwan’s Air Force Intelligence Agency sent off two RB-17 bombers—nos. 835 and 815, successively—to southern China. Min was the pilot on bomber no. 815, taking shifts with two other pilots, Yin-Kuei Hsu and Yan Han.

In addition to the three pilots, eleven other crewmen were on board including three electronics officers, three navigation officers, two mechanics, one communication officer, one airdrop officer, and one airdrop soldier. The mission’s final destination was the southwest region of China. But to get to the region, Min and his crew had to fly over southern Guangdong Province, a risky flight-path considering the strong air defense system in the region.

At about 11:10 p.m., bomber no. 815—returning from Guangxi to Guangdong—was about to fly over a mountain to the sea on the other side. At this moment the aircraft was detected by a radar station of the Guangzhou Military Zone and was shot down, crashing into the mountain in the border area between Enping and Yangjiang Counties. All fourteen crewmen were killed.

Min and Hsiao-Po Meng were married in 1949.

Hwa-Wei and his brothers in Taichung, 1950: (left to right) Hwa-Ming, Hwa-Wei, Min, and Hwa-Tsun.

In this last photograph of Min Lee, taken in 1959, he stands with his wife, Hsiao-Po (back row, second and third from right), and several of his siblings. His son, Hao-Sheng (front, far left) stands alongside his grandparents. By then, Hwa-Wei was in the United States.

As soon as the aircraft was hit, the crew was able to get in touch with the Hsinchu Air Force Base, reporting the fatal shot and pledging to die together with the aircraft. Back then, Taiwan’s air force had a stringent regulation for its airmen: no one should be allowed to become a captive of the Communist army, and every crewman should be willing to die for his country. Obeying the regulation, the entire crew rejected the use of parachutes to escape—their only opportunity for survival—and chose to crash into the mountain with their bomber.

The weather was slightly muggy in Hsinchu. The night of the tragedy, Min’s young wife, Hsiao-Po, felt worried and could hardly fall asleep. She had always been on tenterhooks every time her husband Min was out on duty, but never so much as on that night. The dawn finally arrived. Hsiao-Po opened the window and saw a round hole with a diameter of seven inches that had been dug by Lucky, the family dog. She was shocked. Believing that dogs have an incomprehensible capability of sensing a master’s misfortune, air force family members had always feared seeing a family dog crying or digging a hole. This foreboding sign left Hsiao-Po instantly breathless; she did not know what to do.

It did not take long for the tragic news to spread throughout the Hsinchu Air Force Base. Min’s colleagues and classmates showed up unexpectedly. Their grieving faces suggested something bad had happened. Among them was a friend of Min who had been on the same reconnaissance trip with Min just one day earlier on May 28. He started to cry as soon as he was seated. Seeing the seasoned air warrior fail to control his sorrow, Hsiao-Po came to realize that a family tragedy had happened.5

According to an official military announcement, bomber no. 815 was lost in the air space over Guangdong during its mission; it was then unknown whether the crew members were alive or dead. The Air Force Command covered up the truth to the families of the victims, allowing them to believe that their loved ones were missing while a full search was still going on. Family members clung to any small ray of hope: perhaps their loved ones had made a safe parachuting or had been captured.

Handsome and strong, Min was the idol of his siblings and the pillar of his family. When Lee’s family first moved to Taiwan, Min often helped his father, Kan-Chun Lee—who earned a meager salary as a college professor—with the family expenses by using a part of his monthly income from the air force service. A good husband and father in his own household, Min managed with limited resources to accompany his wife each weekend to dances at the Officer’s Club or to movies at a local theater. He would also take his son out for snacks and pastries. His son, Hao-Sheng Lee, recalled that many pieces of the family’s furniture, including tables, bookcases, benches, and chairs, had been homemade by Min. What most impressed Hao-Sheng was a motorcycle assembled by his late father using spare airplane parts.6

Hwa-Wei was finishing up his Master of Education degree at the University of Pittsburgh when the tragic news reached him. The news was a cruel blow; Hwa-Wei—in spite of limited time together with his brother—had shared a strong bond with Min. In desperation, Hwa-Wei searched every Chinese newspaper that he could find about the aircraft incident with his brother onboard.

Finally, a Hong Kong newspaper article was retrieved from the University of Pittsburgh Library. According to the news report, a Taiwan military aircraft was shot down by the Chinese air force and all its crewmen were found dead. The Communist officers who contributed to this successful attack were to receive awards from Mao Zedong in person. The photo of the airplane wreckage clearly identified bomber no. 815, his brother’s plane. At that point, Hwa-Wei believed that all the crew, including his brother, were dead; what he did not know was that bomber no. 815 had actually been attacked twice.

As the first attack imposed no immediate threats, the crew tried to flee toward the south at the lowest safe altitude. However, as the modified bomber had no defensive weapons, it was soon attacked by a MiG-17. Hit by an air-to-air missile, the plane exploded into pieces 2,625 feet above Enping, Guangdong Province. It was later learned that the air-to-air missiles had been recently acquired by the Communist Chinese air force from the Soviet Union.

Knowing his brother would never come back home alive, Hwa-Wei carefully saved the newspaper piece in his personal file hoping it would be useful someday in the future in locating the crash site. Meanwhile, he could not bear to tell the truth to his parents; they had, however, already learned the heartbreaking news with the assistance of a friend in a high position in the Nationalist Government. Learning of the disastrous loss of her oldest son, his mother aged rapidly. Her hair turned completely gray in just a few days, and she developed heart disease. She was deprived of joy and happiness during the later years of her life.

Min was just thirty-three years old at the time of his death; he was survived by his wife, Hsiao-Po Meng, and his son, Hao-Sheng Lee. The military uniform and leather shoes, which he had prepared for the occasion of Chiang Ching-Kuo’s visit, waited, neatly pressed and shined, in the closet on May 31, 1959, for their owner, who would never return.

On the other side of the Taiwan Strait the pilot Zhelun Jiang, who had shot down bomber no. 815 was celebrated as a hero. Jiang received a special medal from Mao Zedong, a high honor at that time. Having originally joined the air force to fight against Japanese invaders, Min ended his life in an aircraft crash while on a reconnaissance mission over Communist China.

2

In 1982, Hwa-Wei was invited by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) of Canada to join a team of library experts to conduct a special seminar: The Management of Scientific and Technical Information Centers in Kunming, China. The two-week seminar was jointly sponsored by the Institute of Scientific and Technical Information of China and IDRC and was attended by information-center directors from national and provincial government agencies. The trip to China was the first for Hwa-Wei since his leaving China in 1949, thirty-three years before. It opened the door for Hwa-Wei to be invited back to China annually for lectures and consultation by the national library, national and regional scientific and technical libraries, and major academic libraries.