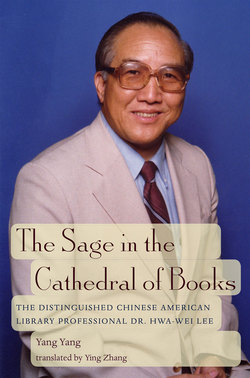

Читать книгу The Sage in the Cathedral of Books - Yang Sun Yang - Страница 18

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

His Education during the Wars

. . . One day, enemies invaded my village.

So I’ve lost my family, my farmhouse, and my livestock . . .

—“On the Jialing River” Lyrics by Hongliang Duanmu Music by Luting He

1

IT WAS NOT easy for Hwa-Wei’s civil servant father to support a big family of seven children on his limited income. From a young age, Hwa-Wei came to understand the hardships of life. Although his well-educated parents hoped that their children could also receive good schooling, Hwa-Wei’s K–12 education was constantly interrupted by endless wars and his family’s frequent relocation caused by these wars.

During the anti-Japanese War, countless students, including Hwa-Wei, were forced to abandon their schools in enemy-occupied areas and flee to safer places. To help those students who were deprived of education by the war, thirty-four secondary schools were established and operated by the central government from 1937 to 1949, including one girls’ school and three schools for returning overseas Chinese students from Southeast Asia. Many of these government-operated schools were quite large: twelve had over one thousand students and thirteen enrolled a student population of five hundred or more. All of those secondary schools, along with the vocational schools, offered free tuition and room and board, effectively subsidizing a refugee student’s education.1

Located in southwest China, Chongqing served as the temporary capital of the Nationalist government during the Sino-Japanese War, providing shelters for refugees from other parts of the country. The year of 1943 saw increasing hardship resulting from the war and an even greater threat from the invaders.

Hwa-Wei and his family went first to Guilin and then moved to Chongqing, where Hwa-Wei’s father worked. Hwa-Wei had just graduated from elementary school in Guilin and was about to begin secondary school. Under an arrangement made by his parents, he and his older brother, Hwa-Hsin, were accepted by the National Number Two High School for Overseas Chinese where Hwa-Hsin was in the eleventh grade and Hwa-Wei in the seventh grade. The school was located in a remote rural area about a day’s journey from Chongqing, with separate campuses about three miles apart for junior and senior high school classes. His mother was very worried about Hwa-Wei, who was then only twelve years old and had never been away from home. But she had no other choice: the government, who operated the school, would provide free education that covered room and board as well.

Founded in August 1941, the National Number Two High School for Overseas Chinese was originally located in the Cheng clan temple of the Jiangjin District, a suburb in Chongqing, as the result of a free land lease to the government for educational use by the Cheng clan. De-Hsi Wang was the school principal appointed by the Ministry of Education.

Situated in the foothills of Longdeng Mountain and alongside the Zuanjiang River, Cheng clan temple was the best building in Jiangjin. However, transportation between Chongqing and the temple was not convenient. One had to walk on foot for about two miles from the temple to Wufuchang, a small town, then another six miles from Wufuchang to Dushi, a township, then, finally, take a bus from Dushi to Chongqing.

At the beginning, all junior and senior high students boarded at school in Cheng clan temple, as they were few in number. Later, the school was expanded with the addition of another campus a short distance away due to the rising number of incoming refugee students from Southeast Asian countries that had also been invaded by the Japanese army.2

Hwa-Wei had quite an adventurous experience during his first trip from Chongqing to the school. His father had negotiated a paid ride with a truck driver along the highway. It was a fully loaded truck, but the driver somehow managed to find additional space by tying some goods to its top. The father and sons squeezed together in the limited space. Once the truck began to move, the tied-up goods seemed to hang by a thread. For most of the trip, Hwa-Wei kept his eyes closed and hoped nothing would fall from above.

About four or five hours later, the three got off the truck when it was about to head in a different direction. Shaking off the dust, Hwa-Wei was finally able to heave a sigh of relief. Despite their continuous jerking for several hours, the goods right above him had not fallen down at all. To complete the journey, Hwa-Wei had to walk for three or four more hours with his father and his brother, Hwa-Hsin, to reach the school.

After hours on the road, it was getting dark, although they had left home in the early morning hours. His father and older brother carried their light luggage. Hwa-Hsin was a thin seventeen-year-old, but he was as tall as his father, and Hwa-Wei felt somewhat secure being with his older brother. The three kept silent while walking cautiously along the potholed country road. Not far away were farmers’ cottages and their surrounding croplands dotted with manure pits here and there. At times, gaunt and dark-skinned farmers would throw a puzzled look at these three neatly dressed and pale-skinned outsiders. Their skeptical gazes made Hwa-Wei feel uneasy, as if he were about to enter another world.

The outlines of the mountain in the distance were gradually obscured by the approaching sunset. In contrast to the bloody and brutal war in other parts of the country, the area seemed peaceful with curls of cooking smoke and the calls of frogs and cicadas. The father and sons hurried along heading toward Wufuchang, literally “a place with five good fortunes,” and into an utterly new life for Hwa-Wei and his older brother, Hwa-Hsin.

2

The junior high campus of the National Number Two High School for Overseas Chinese was in a western-style house made of wood and bricks with an arched door and narrow windows. The two-story building was quite different from the numerous low-rise farmhouses. Local people called it Yangfangzi, “foreign house,” as its original owner was a foreign missionary. About three hundred feet in front of the school flowed the limpid Zuanjiang River.

By the time Hwa-Wei entered the school, there were already some four hundred registered students distributed on the junior and senior high campuses. Educating that steadily growing student population was complicated by extremely underdeveloped facilities and a severe shortage of teaching aids, books, desks, and chairs. To cope with the lack of student desks and chairs, the school sent students to Longdeng Mountain where they would cut and bring back bamboo trunks. Local craftsmen were then hired to make school furniture. A locally made student bench called a zhukangdeng, “bamboo-supported bench,” used two fire-curved bamboo trunks as legs to support another thick bamboo trunk that crossed over them.3

Every low-income student was eligible to receive a school uniform, made of a thick chunky cloth called Luosifubu or “Roosevelt cloth.” The uniforms wore well and were good all year around. Unfortunately, all other daily commodities were of low quality. Students had only flimsy straw sandals that they would purchase or make themselves. Quite a few students were just in their bare feet.

Textbooks and notebooks, frequently in short supply, were made of a poor-quality rough paper and were often shared among the students. The rough surface made writing on those papers difficult when using a pen. Brush pens thus became the only writing tool for students, even for their English homework.4

The living arrangements were equally austere: seven or eight students shared one dorm room furnished with crude bunk beds made of local bamboo. A typical bed was made by loosely tying several bamboo trunks together and was covered only by a thin blanket, which often lost its original color due to sweat stains. Students had to be extremely cautious when lying on their beds so that they would not be trapped in any of the cracks between the two bamboo trunks.

In the summer, the hot and humid weather in Chongqing made the students’ lives more miserable; until late at night, they felt as if they were choking, as if they were enclosed in an airtight cabin. Hungry mosquitoes thirsted for those poor students’ blood. The dank winter did not make the situation better. The twelve- or thirteen-year-old children were still too young to take care of themselves properly. A lack of clean clothes and infrequent bathing resulted in constant outbreaks of lice.

Lice, the size of a sesame seed, were a type of parasite often found in the student dorms. Blood-sucking parasites of exceptional vitality, the tiny insects spread quickly. Once found on one student’s body, the lice, before long, would have infested all the students sharing a room. At the beginning of the infestation, students would feel itchy over their entire bodies. Strangely, the itching feeling would eventually go away. It seemed that almost all of the refugee students had some experience with this widespread infestation of lice. Every time Hwa-Wei went back home, the first thing his mother would do was put all of his clothes in boiling water and wash his hair with liquid medicine.

Each day, the refugee students received two meals, breakfast and dinner, both seldom containing meat. A typical breakfast was up to three bowls of boiled rice soup; but three bowls represented a lucky day. A common dish was often salty beans cooked with hot peppers. Dinner was rice again accompanied by some seasonal vegetables flavored with a few slices of fat pork. The insufficient food supply felt to Hwa-Wei like a cruel punishment; his constant hunger remained deeply inscribed in his memory. It was difficult to fall asleep at night with an empty and gurgling stomach. Most of the time, Hwa-Wei kept a constant lookout for food, but that was in vain.

In his early teenage years, Hwa-Wei started to develop an enormous appetite as his body grew. He hoped that he could get five bowls of rice for each meal, but, on most days, ended up with no more than two. The rice from greedy merchants was always mixed with lots of barnyard millet, sand, and, even, small stones, earning the rice its nickname—“Babaofan,” meaning rice with eight treasures.

During dinner, students, who were always in a hurry for more bowls of rice, spent no time picking out the impurities and learned to eat those “treasures.” One serious consequence of eating “Babaofan” daily was that many students developed appendicitis. Hwa-Wei was one of them.

The hardship of life, however, seemed to have little negative impact on the students’ desire for learning. Instead, they all treasured their peaceful time during the war years. Every morning, reading aloud could be heard throughout the school. Every evening, study groups of three to five students each could be seen in the classroom, dining room, and courtyard. Students with good grades would volunteer to tutor other students with their schoolwork. Looking back, Hwa-Wei remembered the warm orange-colored light coming from the oil lamps in the evening at the Yangfangzi, western-style house, as a symbol of faith and hope for peace in wartime China.

Often seen together with Hwa-Wei were four boys and two girls. One of the older girls called Dejie, “big sister,” really acted like a big sister, always taking good care of the others. She helped Hwa-Wei do his laundry.

Being away from their parents, the boys and girls formed a close-knit group looking after each other. Whenever one of them received a remittance from home, he or she would take the others out for a sumptuous meal, or share some money with others in need. Every time one of them received a food package, the entire group would become excited, sharing the food as if it were a holiday celebration.

During some of the weekends, a group of children would go out and spend a day helping nearby farmers in the fields picking snow peas and digging sweet potatoes, or watering and fertilizing the vegetable crops, in exchange for some pocket money and sweet potatoes. The sweet potatoes were restricted to onsite eating only, so the children wouldn’t stop eating until they became extremely full. In spite of their different personalities and backgrounds, the children helped each other, depended on each other, and endured difficulties together during the national crisis.

This rural area had its unique charms. Wufuchang had abundant orange trees, with plenty of orange orchards near the school. During a golden fall season, the small town was full of ripe oranges, clusters of orange-red among the bright green leaves. The sweet and astringent odor from those ripe oranges irresistibly tempted the students, who were normally hungry, to steal them. Stealing thus became a popular student pastime.

Knowing that there would be no way to stop the children from picking oranges, the farmers came up with a smart idea: They encouraged orange tree adoption by a student at a reasonable price. Once adopted, the tree became the “property” of the student adopter whose name card would be attached to it. The student then had the right to eat as many oranges from his or her “property” as he or she could. This approach was very effective. Farmers made a profit; students gained the pride of ownership. Hwa-Wei, who was one of the adopters, took care of his orange tree. Indeed, it was the first property that he owned.

3

Almost every boy in the school was equipped with a special weapon—a slingshot—which was used for bird hunting. To those starving boys, birds represented their foremost source of meat. After school, groups of boys would often go out on bird hunts, which sometimes took longer than anticipated as the birds gradually learned their lessons and became shrewd.

Hwa-Wei was an expert bird hunter and usually made every shot count. The poor birds would end hung up to dry outside dorm windows after having their feathers torn off, insides cleaned, and their clean bodies marinated with salt. Later, they would be roasted to provide delicious food for the starving students.

Caught in the turmoil of war, the majority of students had nothing to call their own. It was hardly possible for individual refugee students to live on their own without each other’s help. It was truly fortunate for Hwa-Wei to be with a group of peers who stuck together to cope with the hardship. Hwa-Wei felt lucky to have those close friends, while also being able to stay away from the cruelty of the Japanese invaders.

Experience from hardship in one’s early life can become a valuable asset in one’s later life. Through helping and supporting each other in difficult times, one can readily understand the power of mutual aid and the importance of sincerity, forgiveness, friendship, and thankfulness in interacting with others. From his school years at Wufuchang, the young Hwa-Wei came to realize that one can’t survive on one’s own, and the rules of survivorship are kindness, alliance, reverence for others, and togetherness in times of need. These rules have had a tremendous influence on Hwa-Wei and became his guide for interpersonal relationships in later years.

One’s potential and endurance is essentially unlimited. The hardship Hwa-Wei experienced in his childhood set for him an ultimate minimum threshold for living. He is thankful that none of his later experiences were comparable to his years in Wufuchang. Through adversity one can learn to cherish life. The hardship of Hwa-Wei’s early years toughened his soul and tempered his will. Since then Hwa-Wei felt he had nothing to fear.

Hwa-Wei’s schoolmates at the National Number Two High School for Overseas Chinese were mainly from Southeast Asia. When the war ended, the students scattered in different directions. After all the years of chaotic wars and constant moving and relocation, Hwa-Wei, unfortunately, lost contact with the majority of his schoolmates and friends. Now he cannot even recall their names.

4

Government-owned schools were often more disciplined than regular schools. The Nationalist Party government instituted a rigorous core curriculum of civic education courses at the national schools. There were boy and girl scout programs in junior high and military training in senior high schools.5

A good number of school-sponsored extracurricular activities were also available throughout the school year, including swim competitions, ball games, and choir and drama performances, usually involving student participants. In addition to the senior high Haiyun Singing Team and the junior high Zuanjiang Chorus, the National Number Two High School sponsored highly acclaimed basketball and swim teams that were victorious against teams from several local counties. The school was visited by several Nationalist government officials including Tie-Cheng Wu, then secretary-general of the Nationalist Party Executive Committee; Li-Fu Chen, then head of the Ministry of Education; and Tao-Fan Chang, the former provost of the National Political University. Wu delivered the following speech:

You must study hard so as to be able to make contributions to the nation. We will win the war in two or three more years. Upon return to Nanyang [at that time, the Chinese name for Southeast Asia], you could let your parents know how difficult the anti-Japanese War had been, and how the government took great effort to provide education to overseas Chinese students. This country wouldn’t become prosperous and powerful without patriotic support from overseas Chinese.

Hwa-Wei has little memory about what he learned in his classes as he seemed not to have had an interest in any particular subject. What is deeply inscribed in his memory, however, are the pervasive sentiments against foreign invaders and the many popular anti-Japanese songs. Among these was “On the Jialing River” with lyrics by Hongliang Duanmu and music by Luting He, a popular and emotional piece:

One day, enemies invaded my village. So I lost my family, my farmhouse, and my livestock.

Now wandering on the Jialing River, I smell the aroma of soil like the one from my homeland.

Despite the same moon and flowing water, my sweet smile and dream have gone.

The river beneath is sobbing every night; so is my heart.

I must go back to my homeland for the not-yet-harvested cauliflower and starving lamb.

I must return! Return under the bullet shower of our enemy.

I must return! Return across the sword and spear jungle of our enemy;

And I will place my bloody and victorious spear at my birthplace.

The year of 1944 witnessed the steady retreat of the Chinese army as Japanese invaders reached Guizhou Province. The occupation of Dushan County in that province by a small troop of Japanese cavalry immediately put Sichuan Province at risk, and started an uproar among the students at the National Number Two High School. By order of the school administration, every student had to stay in school and prepare for last-minute relocation if needed. However, many hot-blooded young students did not obey that order and joined the Educated Youth Army or the Chinese Expeditionary Force to fight against the Japanese invaders.

Hwa-Hsin, Hwa-Wei’s older brother, had a great hatred of the Japanese and registered without a second thought for the Youth Air Force Academy when he learned of the school recruitment in Chongqing. Founded in 1940 by the government, the academy aimed to train air force reserve pilots. The Chinese air force was rather weak at the beginning of the war. The situation did not improve until the arrival of the Flying Tigers, a nickname of the renowned First American Volunteer Group of the Chinese Nationalist air force, commanded by General Claire Lee Chennault.

The Flying Tigers flew the famous “Hump” air route to transport armament supplies for the Southwest Expeditionary Force and to fight against the Japanese air force. Seeing the reduced potency of the Japanese air force increased Hwa-Hsin’s admiration for the Flying Tigers. He started to dream about becoming an airman.

Their parents, originally concerned about young Hwa-Wei, had hoped his older brother could take care of him, somewhat, at school. However, Hwa-Hsin had only been at the school for one quarter before he left for the Youth Air Force Academy, leaving thirteen-year-old Hwa-Wei on his own. At the moment of seeing Hwa-Hsin depart, Hwa-Wei felt panic and helplessness, and he really wanted to call out to his older brother to beg him not to walk away. However, he knew that would not work and that he had to face the future on his own. Gazing at his brother’s receding figure, Hwa-Wei blinked away his tears.

5

August 1945 was a major turning point in World War II with increased Soviet involvement and America’s dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Hwa-Wei’s family was still in Chongqing. Every day street-corner newspaper boys would shout victorious war news. Growing excitement and joy were filling the damp air, and smiles were back on pedestrians’ faces. Having endured eight years of extreme hardship from the Japanese invaders, the Chinese were ready for the long-awaited victory and peace.

With the end of the Sino-Japanese War, the Nationalist government moved back from Chongqing to Nanjing. Japan declared an unconditional surrender on August 15, 1945. Three weeks later on September 9, a mass celebration was held in the capital city. Streets were filled with cheering crowds, colorful lanterns, and bands, accompanied by the sounds of loud gongs and drums.

Some of the major avenues were decorated with archways made of pine and cypress leaves. Those archways were decorated with eye-catching golden letters, spelling the words “Victory” and “Peace,” and streaming national and Nationalist Party flags, with a red “V,” for victory, sign placed between the two. The gate of the Central Military Academy held two signs: “For Forever Peace” and “General Headquarters of Chinese Land Forces.”

At 9:00 a.m., the signing ceremony of the Japanese Surrender (China War Zone) began at the auditorium of the former Central Military Academy. Yasuji Okamura, the commander in chief of the Imperial Japanese Army in the China-Burma-India Theater, along with six other Japanese representatives, bowed, hats off, to the Chinese government representatives led by General Ying-Chin Ho, who, ironically, was a former student of General Okamura at the Imperial Japanese Army Academy.

Japan had regarded China as a hopelessly backward country that could not withstand a single blow from modern post-Meiji restoration Japan. This perception was based on the weakness and corruption that had developed during the last century of China’s Qing dynasty, founded in 1644 by Manchus, and the country’s lack of unity after the 1911 revolution that ended the dynasty and established the new Republic.

The Japanese failed to realize that their invasion of this ancient country had set off a time bomb. What they had not understood was that vast and populous China had also been undergoing a reformation with westernized cultural components and an enhanced national consciousness, but one growing at a slower pace than their own. Tanaka Giichi’s statement about taking over China as the first step to conquering the world was ultimately proved to be wrong.

Hwa-Wei (front row, third from the left) in his junior year at the National Han-Min High School in Guilin.

Hwa-Wei (front, third from the left) was a member of his high school basketball team

Hwa-Wei (first from left) and friends in his senior year of high school at the Provincial Taichung First High School, Taiwan.

When Hwa-Wei’s family returned to Nanjing in the fall of 1946, there were still many Japanese soldiers waiting to be repatriated from China to their home country. Wandering on the pier in the rain, the Japanese soldiers lined up with heads down, showing no reaction to the outrageous curses, kicks, and thrown stones from angry Chinese citizens. Seeming indifferent, those low-spirited, defeated soldiers lost their wartime swagger and moved like animated corpses.

After seeing this scene, all the hatred that had built up during the past eight years in Hwa-Wei’s heart was suddenly gone. Instead, Hwa-Wei felt sympathy for those down-and-out Japanese soldiers whose expressionless faces also seemed mixed with a bit of relief—the war was over and they were going home alive. Indeed, he understood, they were merely the tools and victims of the militarism of their misguided government. The true war criminals, he felt, should be seen as those who had initiated and directed the war.

Nanjing was a city where Hwa-Wei had spent most of his childhood years. He first moved to the city with his parents at the age of two and stayed there for four to five years. His second residential period in Nanjing was between the end of the Sino-Japanese War (1945) and the beginning of the resumed civil war between the Nationalist and Communist parties in 1947. During those two years, Hwa-Wei actually stayed in the boarding school of the First Municipal Middle School of Nanjing on his own, while the rest of the Lee family relocated to Peking after a very short stay in Nanjing. There were no worries for his parents this time around as Hwa-Wei was already accustomed to life at a boarding school and had learned to take care of himself.

Hwa-Wei left Nanjing for Guilin in 1947 to join his parents and siblings, who had just withdrawn from Peking to Guilin. It was in Guilin that Hwa-Wei was able to finish his tenth and eleventh grades at the National Han-Min High School, a famous state-run school in Guilin.

Notes

1. “Education in Wartime China,” The Whole History of China, part 20, 372.

2. Zhenshi Yi, “National High Schools for Oversea Chinese during the Anti-Japanese War.” Oversea Chinese Affairs First Journal, No. 5, 2006. http://qwgzyj.gqb.gov.cn/qwhg/132/755.shtml.

3. “Brief History of the Second National Overseas Chinese High School”, Special Issue of the History of Private Overseas Chinese High School, the First National Overseas Chinese High School, and the Second National Overseas Chinese High School. (Hainan: Hainan Overseas Chinese High School, May 2013. 13-23.

4. Ibid.

5. “Education in Wartime China,” 373.