Читать книгу Yigal Allon, Native Son - Anita Shapira - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 2

Kadoorie Agricultural School

Allon’s first meaningful introduction to the world beyond the horizon was at the Kadoorie Agricultural School. He entered Kadoorie as a child of Mes’ha and emerged from it determined to leave his native village.

Once Reuven Paicovich realized that his youngest son was not to benefit from a Mikveh Israel education out of the PICA’s pocket, he began to nurse a fresh hope: Yigal would attend the newly built school next door to Mes’ha, on lands adjoining the Paicovich holding at Um-J’abal—meaning Kadoorie. The public storm surrounding its founding was typical of the Jewish Yishuv at the time, when Zionist fervor imbued every deed, big or small, with value and significance beyond ordinary mortal measure. Only in this sort of atmosphere could a school’s establishment turn into a national project, an open controversy, the focus of animosity and suspicion toward the British authorities, and a source of pride and sense of overall achievement for the Jews. Kadoorie—before it ever even rose—came to represent British injustice toward the proud Jewish Yishuv.

It all began with a misunderstanding: the last will and testament of one Ellis Kadoorie, an Iraqi-born Jewish millionaire who had lived in Hong Kong and bequeathed a third of his legacy, £1 million, to his majesty’s government for the building of a school in his name in Palestine or Iraq.1 The bequest, soon enough, was given the following complexion by the Zionist press: an upright Zionist Jew wished to leave money for a Jewish school in the land of Israel, when along comes “wicked Rome”—that is, the British—which helps itself to part of the gift for an Arab agricultural school in Tul Karm.2 This Zionist interpretation was passed down as bald fact from one generation of Kadoorie pupils and graduates to another.

As it happens, the government of Palestine was interested in building a Jewish high school in Jerusalem. But the legendary teacher Asher Ehrlich threw a spanner in the works: he began to lobby for a Jewish agricultural school around the Jezreel Valley, and, in 1925, a whole series of institutions, colony councils, community bodies, and so forth signed and submitted a petition to High Commissioner Herbert Samuel to earmark the funds for an agricultural school in the Lower Galilee and the glory of local education. Mes’ha added its voice to “the people’s will,” as it stated in its application to the high commissioner.3 The government of Palestine endorsed the idea of a Jewish agricultural school similar to the Arab school in Tul Karm, and the question of location came up for discussion. Several sites vied for the honor and the not inconsiderable benefits—a road, a well, and a boost to the consumer population. The felicitous choice ultimately fell to a hillock between Sejera and Mes’ha, bordering on a-Zbekh lands at the edge of the Tabor, and, following divine and human delays, construction began in 1931. The edifice designed by government engineers was expansive and tasteful: the barn alone was fairer than any of the buildings in all of the local colonies put together, as were the living quarters, classrooms, laboratories, and other enhancements.

The school belonged to the government of Palestine, coming under its Department of Agriculture. The department financed it, was to appoint the principal and teachers, and set the curriculum. At one of the early planning stages, Herbert Samuel suggested that it be an English school, only to provoke more furor: Jewish money was to go for a non-Hebrew school in the land of Israel?! The British backed down. They promised to build a Hebrew school with a Jewish principal and teachers, and a number of Yishuv representatives on the school board. Hereafter, government officials consulted with the Jewish Agency (JA) on all school matters. In Tul Karm, in contrast, the principal was indeed English and the school’s character was British colonial.

At the suggestion of the JA, Shlomo Zemach was appointed principal.4 This ideal candidate was an agronomist, a writer, and an educator, and the zealous champions of Hebrew could breathe easy.5 The fact that he belonged to the Ha-Poel Ha-Tza’ir Party, as did Chaim Arlosoroff, the director of the JA-PD at the time, presumably did not harm his nomination. He was appointed in 1933 and began to prepare actively for the school’s opening in 1934.

Allon acceptance at Kadoorie involved protracted negotiations between Paicovich, Zemach, and British officials about the boy’s fees. Paicovich was of the opinion that the school’s proximity to Mes’ha entitled his son to a full scholarship. In his address to Mes’ha, High Commissioner Arthur Wauchope had mentioned that one of the village children had been accepted at the new school. Paicovich understood that “the high commissioner meant that the lad study at the government’s expense for the benefit of the village nearest the school.”6 The motif the “lad of the village nearest the school” was reiterated in Paicovich’s letters as sufficient cause to relieve him of payment. The fees had been set at Palestine £24 per year, no mean sum at the time: an agricultural worker earned only 20 pennies (grush) a day, and a teacher about £5 a month. Given Mes’ha’s financial straits, it is hard to imagine that Paicovich could come up with the full sum. Zemach wanted a local child at the school and was sympathetic to Paicovich’s circumstances. To make it easier for him, he employed Allon for about a year in the school’s construction prior to its opening, in the hope that the boy would save up for the fees.7 Though the fate of Allon’s wages is undocumented, they certainly did not go for fees. After Zemach finally digested the nature of Paicovich’s objection to school fees, he referred him to the Department of Agriculture. Paicovich did in fact obtain an exemption—but only for the cost of a day pupil. Since boarding was compulsory, he had to make up the difference, Palestine £12 per year. He was thunderstruck: part of the sum had already been waived and he had imagined that boarding would be a pittance! He delivered an ultimatum to Zemach: either Zemach would allow Yigal to attend for £6 a year or Paicovich would remove the boy from the school.8 Zemach ultimately agreed.9 Paicovich’s “thank you” letter, announcing the first remittance in December 1934, quite some time after school had started, was penned by Allon.10 How the boy felt throughout the haggling, which smacked of wretchedness, both Paicovich’s and the village’s, is anybody’s guess.

The school officially opened on 20 June 1934 at a state ceremony under the patronage of the high commissioner. Regular studies began that autumn, following a summer preparatory course, which Allon attended. The school was to teach agriculture to graduates of the tenth grade. The first twenty-four pupils were handpicked out of some two hundred candidates,11 an elect group boasting a number of very bright stars indeed.

Yigal first met his classmates in the summer of 1934. The new pupils—strangers to the setting and the landscape, to farming and Arab neighbors—found themselves welcomed by a fair-haired, blue-eyed youth riding bareback. Most of them were around sixteen; he was about a year younger—no mean difference at that age. But he knew the place and its ways, while they were outsiders. Apart from Amos Brandsteter of Yavne’el, only Yigal hailed from the Lower Galilee. Moreover, he was familiar with Kadoorie, having worked there while it was being built.

The curriculum represented a compromise between applied and theoretical agriculture. Theory was on a high level. The teachers had been carefully drawn from top professionals in different fields: animal husbandry, chemistry, physics, economics, soil science, fertilization, and so forth. The British who designed the program were partial to the assumption that farmers needed to know nothing but their trade, and they limited the curriculum to scientific and technical subjects. Humanities did not feature in the formal syllabus.12

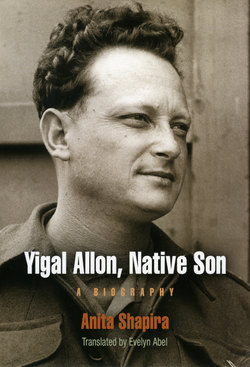

Figure 5. At Kadoorie Agricultural School. Allon is standing, third from the right. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Allon House Archives, Ginnosar.

The standard of education was far more demanding than Mes’ha’s schooling, and, after studies began, Allon found himself among the weakest pupils. He found physics and chemistry particularly hard,13 and his first half year at Kadoorie required supreme effort. Applying himself with determination and diligence, he managed not to fail. His teachers helped him, especially Zemach, whose eye he had caught. But more valuable still was the help he received from classmates. Those who had attended good schools, such as Amos Brandsteter, Arnan Azaryahu—nicknamed “Sini” (Chinese) because of his slanted eyes—and top student Joel Prozhinin, who had won the Wauchope Prize, helped the poorer students, such as those who came from Kefar Giladi and our lad from Mes’ha. The school atmosphere was not competitive. Rather, there was a sense of togetherness and companionship with the strong aiding the weak.

After his first half year Allon was able to sigh with relief, believing himself equal to the task he had undertaken. He remained an average student until the end of his career at Kadoorie, neither shining nor disgracing himself.

Allon’s academic standing did not affect his social position. He made up for his lack of scholarship with traits and talents learned at Mes’ha: he could ride a horse, hitch a wagon, wield a two-mule plow. Who knew farm work as well as he? City boys found it hard to rise to barn work or fieldwork at the crack of dawn; Allon was used to it. After his training at home, the four hours of daily work demanded by Zemach were a piece of cake. The farmer in him, nature’s child that he was, made him a model at Kadoorie. Sure, it was good to know chemistry, but other knowledge was just as important: how to clear the land of stones, how to plow, to plant, to sow, to reap. These skills soon propelled Allon into a strong social position, whatever his intellectual achievements may have lacked.

Kadoorie was not the Eton of Eretz Israel, though more than a few of the country’s prominent sons were to attend it over the coming decade. It did not turn out gentlemen or prepare students for high society. It did not provide a broad education, but it strove to produce highly trained farmers for the colonies and the settlements of the Labor movement. It did, however, abide by some of the norms and behavior of English boarding schools. Attending boarding school meant being cut off from home, from family, and from familiar surroundings. Pupils were allowed home on holiday once every three months. Parent’s day was held at the school twice a year. Pupils seem to have found ample compensation for the break with home in the fellowship of peers and the warm relations they developed with teachers.

It was a boys’ school, as was common for boarding schools in Britain, though less so for those in Palestine, where secular society championed women’s equality and mixed learning was customary. In fact, shortly before Kadoorie’s inauguration, the Ben Shemen Youth Village had opened under Dr. Siegfried Lehmann as a joint boarding school for boys and girls. The absence of girls at Kadoorie certainly affected the school experience. The emphasis tended to be on male qualities, such as physical prowess, practical jokes, and a degree of uncouthness. To counter the lack of female company and cut their manly teeth, the boys would pay visits to Nahalal, where there was a girls’ school, to Tel Yosef, where there was a youth village, and sometimes even to faraway Haifa.

Kadoorie also adopted from the education of an English gentleman the code of honor. Two stories exist as to its source: one ascribes it to Zemach, the other to the student body. Either way, there was a gentleman’s agreement against copying during exams, with teachers showing their trust by staying out of the classrooms. As often happens when supervision devolves on a peer group, the boys were more zealous than their teachers about the honor system. If anyone faltered by glancing at a textbook, the student council soon informed Zemach of the breach (without, of course, supplying the malfeasant’s name) and called for reexamination. The code held good for smoking as well. Because Zemach’s wife, a doctor, deemed the practice most harmful, a decision was made—and kept—to ban smoking from the school grounds.

The school day was very full: in the summer, pupils would rise at five; in the winter, at six. Cowhands rose at three. Classroom work lasted six hours, and farm work, four. Formally, pupils finished their duties at 4 P.M. and were free for homework, preparing for exams, idle—and not so idle—conversation, games, or going out. The boys took their studies seriously, especially those such as Allon who found the going uphill. Lights-out was at 9 P.M., but studies often stretched late into the night with the help of a flashlight.

Sports featured strongly in student life and were encouraged by the school. Dares—such as scaling the Tabor in pouring rain—were run-of-the-mill. But the favorite pastime was soccer. The small Kadoorie student body turned out a winning team for the Galilee Cup, thus stretching its reputation well beyond the region. Soccer held the boys and filled hours of play and talk. In a friendly game between the two Kadoorie institutions, the triumph of the Jewish school over the Arab one was veritably a national honor.

Actually, the boys as well as Zemach were highly conscious that their every deed and prank reflected on the Jewish image in British eyes. The very fact of British supervision charged teachers and students with guarding Jewish honor before the powers-that-be. Every few months, they were treated to a visit by Mr. Dowe, the inspector of the Department of Agriculture of the government of Palestine,14 the momentous occurrence occasioning a feast. The school kitchen would cook up a storm compared to the regular fare, preparing, among other things, roast chickens. Being especially fond of the dish, the students—according to one story—would break into the kitchen and generously partake of the luxury before Dowe even arrived. Or, according to another story, they would burst into the dining room as soon as Zemach, Dowe, and Dowe’s entourage had left it and fall upon the leftovers with the gusto of adolescent boys. Once, Dowe forgot something in the dining hall and he returned with Zemach only to catch the boys red-handed. Zemach did not know where to hide: what would the British think of Jewish conduct now?!15 Dowe, the son of a modest farming family and a swineherd in his youth,16 presumably did not regard the boys’ actions as overly “disgraceful.” But Zemach and his boys were mortified.

The consciousness of guarding the national honor also came to the fore in another incident: two of Kadoorie’s boys were invited to dine with the high commissioner. One of the two, Sini, was seated next to a British official. All of the warnings he had been given about Jewish honor rang in his ears and whenever the waiter offered him tantalizing delicacies, he courteously asked for a mere mouthful—after all, everyone knew that in polite company one did not exhibit appetite. Sini thus walked away from the meal as ravenous as he had come to it. Amos Brandsteter, in contrast, had been seated next to a Jewish official and had indulged his appetite to his heart’s delight.

School subjects, as described earlier, were aimed at enriching the mind but hardly the soul. Pupils coming from regular high schools arrived at Kadoorie with the intellectual and emotional baggage instilled by humanist-oriented curricula. History, literature, Bible were the foundation stones of education in the city. Allon had received none of this emphasis. Zemach, an author among agronomists and an agronomist among authors as he liked to refer to himself, was alert to the paucity of Kadoorie’s syllabus. He would take the time to converse with students about literature and even ask the capable ones to write papers, which did not fall short of any produced at nontechnical schools.17 For some of the pupils, including Allon, the talks with Zemach opened up new worlds.

But on the whole, their world was small and circumscribed, centering on peers and school matters. They were not bothered by “big questions.” This was true also of top students from educated bourgeois homes. Life revolved around exams, teachers, pranks, soccer, work, and girls—they were ordinary adolescents, after all. The pecking order was determined by physical excellence.

Like the rest of Yishuv society, the boys were affiliated with either the Left or the Right, either Labor or Revisionists. The first twenty-four, as it happened, were equally divided between Ha-Noar Ha-Oved, the youth movement of the Labor Federation (Histadrut), and Maccabi Ha-Tza’ir, which was connected to the middle class. Everyone anxiously awaited the arrival of a twenty-fifth student: Israel Krasnianski, the tie breaker, tipped the scales in favor of Ha-Noar Ha-Oved,18 resulting in the election of an all-“socialist” student council (consisting of Prozhinin, Brandsteter, and Sini). The elected members were a conscientious lot, but their sense of responsibility was no match for Sini’s desire to get his hands on a steering wheel. One night, he and a few others “borrowed” the agricultural instructor’s car and set off for Afula. They knew a heady sense of mastery—they could drive! True, they could not find the rear gear, but this did not make the occasion any less momentous. When it was time to turn around, they simply lifted the vehicle and faced it in the right direction. Back at Kadoorie, they learned that the Arab guard had spotted their exit and reported them to the principal. Zemach made it plain that recklessness was inconsistent with a seat on the student council. By consensus, which was common practice at Kadoorie, Sini was ejected, making room on the council for a member of Maccabi Ha-Tza’ir—Allon.19

Allon had been involved in Maccabi Ha-Tza’ir at Kefar Tavor, where he had actually initiated and established the Mes’ha branch, an act that was a clear reflection of the village public mood: on the right of the political spectrum, yet not too far right. Maccabi Ha-Tza’ir was a middle-class, quasi-youth movement. Apart from socializing, its dominant activity was sports. Most of all, for the youth of Mes’ha, it represented a contrast to the Left, the Left that maligned them and demanded that they employ Jewish labor. Given Mes’ha’s conditions, the mere fact that local youth organized to found a branch of the league was in itself an achievement. Allon’s role in the affair had placed him at the forefront of Mes’ha’s youth. His membership in Ha-Maccabi Ha-Tza’ir showed that he toed the line, that he accepted his father’s worldview. He may have belonged to a poor family in a poor village, he may have been highly conscious of his poverty, but he likened himself to members of the middle class whose rituals and traditions he shared. His friends at Kadoorie, in contrast, who were pampered lads from “established” homes, saw themselves brandishing the socialist flag and identifying in their mind’s eye with the wretched of the earth.20 In substance and the type of youth it attracted, Maccabi Ha-Tza’ir had a petit-bourgeois air. Its “respectable” role models wore cravats at a time when the rest of the fledgling country still sported frayed collars. It lacked the drama and protest of Betar (the Revisionist youth movement), the daring and dedication of Labor youth. In an era when the young thirsted for commitment, it defended no cause. It breathed flat air, free of either danger or great dreams.

Allon remained true to Ha-Maccabi Ha-Tza’ir even after coming to Kadoorie and being exposed to other ways and ideas. However, his co-option to the student council as its representative marked the start of a fast friendship with members of Ha-Noar Ha-Oved, especially Amos and Sini (who was pardoned some months later and restored to the council). The three were to remain on the council until the end of their studies.

His friendship with Ada Zemach scored him an important social point. The principal’s daughter was the only flower in Kadoorie’s female desert. Ada studied at Haifa’s Re’ali School and thus did not live at Kadoorie, but she came home on weekends and vacations. Pretty, delicate, learned, she was unlike any of the girls Yigal had ever met. Though a couple of years younger than him, she was his intellectual superior. She loved literature, belonged to the Left’s literary bohemia that sprouted up around the rebellious poet Alexander Penn, read avidly, and was open to the unconventional and the avant-garde. To Allon, she symbolized the whole new world he was introduced to at Kadoorie. To Ada, a city-slicker, the handsome Allon had the appeal and freshness of a farmer and boy of nature. She was impressed by his horsemanship and attracted by his simple manners. What’s more, the fact that he was older than she and more savvy about boy-girl relationships made up for her scholarly lead. She took pleasure in parading him before her high school friends when he visited her on weekends. At the same time, his involvement in Maccabi Ha-Tza’ir and his petty-bourgeois traits somewhat marred the image of the natural farm boy she had constructed. Still, the fine pair were not together often enough to play up the shortcomings, and their missing one another went a long way to stifle doubts that might have surfaced in a closer relationship.

Figure 6. Ada Zemach. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Allon House Archives, Ginossar.

Their friendship began when Allon worked at Kadoorie before school started. It lasted for four years, until Ada finished high school and Yigal decided to join the Ginossar kibbutz group. It was a young love, significant to both. In the best romantic tradition, they were mostly self-absorbed when they were together, hardly ever discussing either Kadoorie or the great big world. Ada’s head was full of the Spanish Civil War. Allon, like most Kadoorie boys, took no notice of it. But he certainly had a thirst for literature—her chief interest. He was at home in her house and often met her father, which only whetted his appetite. The pupils at Kadoorie liked to believe that Zemach and his wife did not overly approve of the relationship between their daughter and the Mes’ha farm boy, but the truth is that they accepted him as part of the family. He continued to show Zemach respect until the end of his life.21

The idyll was shattered in Yigal’s second year at Kadoorie. Beginning in the autumn of 1935, tensions rose in the country. The fallout from Mussolini’s war in Abyssinia sowed war panic and the economy slumped. A shipment of Haganah arms, hidden in a crate of cement, was intercepted at the port of Jaffa and shook up the Arab street. Even at Kadoorie, events in the country suddenly jerked the boys to attention. Sini reviewed the situation in a letter to his parents, ending on a note that smacked of Zemach: “Hopefully, it will be possible for us to go on building and consolidating. And if it is decreed that the world revert to the pre-flood era, it will find us ready to resist.”22 This curious contradiction between the apocalyptic forecast and the firm confidence that the pupils of Kadoorie (or of the Yishuv) would prevail seems to have been a basic element of education in Eretz Israel: it inculcated a sense that there was nothing the people could not do, no test the people could not meet. The consciousness that catastrophe was sure to come, and that the people would be called to stand in the breach, was inbuilt in the ideology. The appearance of these components in Sini’s letter of October 1935 hints at an emerging awareness among the young that they were growing up into a dangerous world with a direct bearing on them; it was as if, suddenly, the curtain blocking their field of vision had risen, and the horizon stretched into the distance.

Kadoorie’s small world suffered also from a tension of its own. Zemach inspired admiration from the pupils, but he was less able to manage the teaching staff, and his relations with some of them soured.23 In his view, he owed allegiance to the British authorities who had appointed him to head the school. Precisely because he had always been a Zionist and had been nominated by the JA-PD, he sought to show one and all, and particularly the British, that he comported himself correctly as warranted by a state school.24

His prudence in dealings with the British was not to the liking of teachers, employees, and even pupils. Wagging tongues began to accuse him of being overly solicitous about British money and British property, and they found willing ears among the students. Matters came to a head with Zemach’s decision to dismiss the teacher Siegfried Hirsch. In his memoirs, Zemach attributed the decision to the latter’s frequent, unjustified absences. Hirsch apparently managed to persuade the pupils that he was being fired for being involved in the Haganah and because Zemach, a British lackey, objected to the Haganah operating in the school framework.25

The reaction of the pupils came close to rebellion. They resolved to intercede to rescind Hirsch’s dismissal. To do so obviously meant to bad-mouth Zemach before the British. Their national responsibility aroused, the staunch champions decided first to consult the man who would be most interested in hearing about the ousting of a nationalist teacher from Kadoorie—that is, David Ben-Gurion, chairman of the JA Executive. The natural candidates for the mission were two council members affiliated with Labor, Prozhinin and Sini. One fateful day, Sini telephoned Ben-Gurion’s home, introduced himself as the son of a man known to Ben-Gurion, and said that he and a few others from Kadoorie’s graduating class wished to discuss a serious issue with him. Sini explained that they could come only in the late afternoon or evening; Ben-Gurion replied that he would see them whenever they came. And so it was: the two lads snuck away from Kadoorie after the day’s activities and hitchhiked to Tel Aviv, arriving around midnight. Ben-Gurion greeted them in his pyjamas and heard them out in silence. They then gave him the draft of the petition they meant to send to the authorities, and he promised to consider the matter.26

Memory can play false. According to our heroes, the episode ended with Ben-Gurion’s apparently burying the document. As it turns out, however, the affair was serious. The student council took two extreme actions: first, it sent off a letter to the high commissioner asking that Hirsch’s dismissal be revoked. Second, it sent off a formal petition to the JA-PD, declaring that “the students’ faith in the [school] leadership had been thoroughly shaken” and demanding that the Yishuv leadership and those in charge of the school “look into the situation and reverse it.” The letter was signed by the twenty-four pupils of Kadoorie’s first graduating class.27 For Zemach, it was a slap in the face.

The first signatory was Allon, and the petition even looks like it was written in his hand. He still belonged to Maccabi Ha-Tza’ir and was not chosen to approach Ben-Gurion. But—eagerly or not—he was a full partner to the student conspiracy against his benefactor. Throughout this difficult period for Zemach, Allon continued to come and go in his home as he pleased. In his talks with Ada, the subject never came up, not once. Zemach was truly upset: not only had Allon placed himself against him, on the side of the teacher and pupils, but he had done so in secret, without telling him about it. “Yigal was a Mes’her bokhur” (a Mes’ha sonny) Zemach noted, filling the epithet with all his scruples about behavior he considered treacherous, ungrateful, and cowardly.28

The last peace-time activity to take place at Kadoorie was the trip of the graduating class to Egypt. It was to cap the end of studies and inaugurate a tradition of graduate trips to a neighboring country also under British rule, except that reality intervened and the school trip in early 1936 was apparently the only one of its kind. Arab riots soon broke out, upturning everything. Zemach had meant to lead the trip, and the students were to be the guests of Egypt’s Department of Agriculture. But after learning of the student rebellion, Zemach announced that he would not be accompanying them. Nevertheless, he made sure to tell the council that it was responsible for the students’ behavior and it was to make sure that they not disgrace the Yishuv.29

In April 1936, the Arab Rebellion erupted. (It was known in the Yishuv as the 1936–39 Disturbances.) It set into motion a new era, eventful and fateful for the Jewish Yishuv, which had known demographic growth, economic boom, and steady reinforcement since 1932. All of these developments had been viewed by the Arabs with dismay. While they too enjoyed prosperity, it could not compensate for their apprehension that the land was slipping away from them, changing virtually overnight from an Arab to a European country. The Rebellion was aimed at halting the process, at preventing the Jews from becoming the dominant factor in Palestine.

Tension was thick. Life at Kadoorie went on, but the environs seethed. The pupils felt left out of the action: the school was protected by British police, and despite its relative isolation it was not in any danger. The boys were asked to keep to themselves and avoid unnecessary sparring with Arabs. This was the local translation of the Yishuv policy of restraint, adopted in the face of the Arab revolt and terror. Jews were to demand British protection rather than embark on vengeance or retaliation. In practical terms, this meant holing up within Jewish settlements, never straying beyond the fence. Fields and barns were torched, trees cut down, years of toil lost—with no reaction. There were reasons for this policy: the Yishuv leadership hoped that this time—unlike the course they had chosen in 1929—the British would be unable to portray the unrest as a clash of two peoples; it was eminently clear that the blame lay with the Arabs and their resort to violence. The British government would have to defend the Yishuv from attack and, perhaps, even issue it the necessary means of defense. The hope was that the Yishuv would be allowed to set up a legal, Jewish defensive force, supervised and financed by the British. None of these considerations of high policy made it any easier for the boys of Kadoorie. They itched to be let loose for daring, heroic, patriotic exploits.

At the start of May 1936, a few weeks into the riots, Kefar Tavor’s water facility was set alight about 150 meters from Kadoorie’s fence. The arson was committed at night when the pupils were dead to the world, hearing nothing. The two resident policemen did not allow the pupils to be woken in order to extinguish the fire, either because—as they said—they did not want the tracks of the perpetrators blurred or because the firefighters would make excellent targets in the light of the flames. In the morning, the boys rose to a sooty pump, a broken motor, and a burned-down building. Here was an exploit indeed right under their noses—and they had literally been caught napping. Great was their shame, which was made worse by the rejoicing of Arabs released from custody after the scouts failed to discover anything.30

One summer day, a-Zbekh shepherds were spotted leading their flocks up Kefar Tavor’s fields next to Kadoorie. The fields were Paicovich’s, at Um-Jabal. Allon and a few of the boys and laborers ran to grab hoes to chase off the trespassers. The shepherds started to retreat, then stopped, raising instead the Arab alarm, the Faza’a. Bedouin flocked to the scene and soon outnumbered the contigent from Kadoorie. But the boys stood their ground. They conducted an orderly battle of retreat and even managed to wound seriously two of the Arabs; they themselves incurred no injuries. Meanwhile, the action had been discerned at Kadoorie. Led by Zemach, the teachers took two of the rifles on the premises and set out as reinforcements. Allon described the fight as a battle he had headed, organized, and directed. This leadership role is not remembered by other participants. In any case, it seems that Yigal called out to the teachers to fire in the air to miss, for fear of escalation. He had absorbed Mes’ha’s long-standing code: caution lest blood be spilled, yet resolve to give as good as one got.31

But this was not yet the end. A-Zbekh Arabs complained to the authorities of aggression and the police descended on Kadoorie to detain the pupils involved.32 They, including Allon, were carted off to jail in Tiberias. The adventure did them no harm and certainly added to their peer prestige. Allon was proud to have carried on the family tradition: both his father and brothers had been “privileged” to imprisonment and captivity under the Turks.33 The whole episode took only a few days. The boys were released on bail paid by their parents.

Like almost everything else in that period, the trial of Kadoorie’s youngsters turned into a national brouhaha. The JA-PD engaged the Haganah’s hotshot attorney, Aharon Hoter-Yishai, and paid his legal fees of Palestinian £8.34 Hoter-Yishai listened to the youngsters and told them what to say in court. After talking with them for half an hour, he chose Allon to act as the key witness. This appears to be the earliest evidence about the sort of impression Allon made on strangers. Hoter-Yishai chose a lad he judged to be above the rest: handsome, credible, articulate, naturally shrewd, and with a good grasp of the situation. If the brawl did not distinguish Allon from the others, his court appearance crowned him spokesman and ringleader.35 In the courtroom, Allon claimed self-defense against trespassers and physical assailants. This version, buttressed by the personality of Hoter-Yishai, who overawed the prosecutor, was accepted by the British judge and the boys got off scot-free.36

In the summer of 1936 Kadoorie was shut for security reasons and the students were sent home. The truth was that the boys were not eager to stay to defend the school when their parents’ farms were in danger. Studies apparently resumed in December and on 24 March 1937, Kadoorie’s first graduating class completed its studies. Allon was nineteen.

Many of the pupils had joined the defense forces during the school’s closure. Sini served as a ghaffir (a temporary police guard) at the village of Kefar Javetz, under a British sergeant. Brandsteter and Allon were guards in the bloc of Tiberias and the Lower Galilee, under Nahum Shadmi (Kramer) of the colony of Melahamiya. The duties seemed to be the same at every location: guard duty by day and defense patrols by night. “Since we have arrived, there have not yet been any shots”—Sini grumbled in his letter to his parents—“let’s hope this will change or I’ll die of boredom.”37 By his lights, the situation did not improve even though the ghaffirs at Kefar Javetz served as “a mobile squad to danger spots,” that is, they were the spearhead of the defense forces. “As for my spirits, one should not hope for any improvement before one decent attack because I am being consumed by idleness,” Sini continued to carp two weeks later.38

Allon didn’t complain. As ever, Mes’ha offered stirring pursuits of Arab marauders. The chase was the same as it had always been except that now Yigal proudly boasted a guard’s headgear (the kolpak—a tall fur hat), his possession of live ammunition was legal, and killing was permitted. At night, he and his friends would head for Mes’ha’s fields to douse fires, putting themselves at risk from sniper shots from Arab gangs.39 On these escapades he did not appear exceptional.

At this stage in their young lives, the boys regarded the fights, chases, gunshots, and danger much as though they were aspects of a thrilling game. Their parents may have worried about them, but they themselves had not yet experienced loss, and the danger was intoxicating, a boost of alertness and a burst of adrenalin. Only youths untried in the pangs of war could write to his parents as Sini did.

The glory of defense service aside, agricultural settlement retained its rank as the crowning achievement of practical Zionism in Eretz Israel. Out of twenty-two graduates of Kadoorie’s first graduating class, seventeen aimed to be farmers. The others chose either to study further—mainly agriculture, abroad—or to enter public service.40 Many of them regarded higher studies as near treason.41 In those few months between the resumption of studies and the end of the first graduating class, when the young men talked about plans for the future, one of the ideas touted was the establishment of a fifty-unit farm. As graduates of a government school, they hoped to be in line for assistance: to obtain a holding, preferably on state lands in the Beisan Valley frontier, where both water and danger were abundant. Their eyes lit up at the thought of promoting the national good while treading a common path. In January 1937, thirteen members of the first two graduating classes organized and applied to the Government of Palestine for a piece of land.42 The signatories included Arnan Azaryahu (Sini), Joel Prozhinin, and Yigal Paicovich.

The application was denied. The government replied that it did not intend graduates of Kadoorie to found a settlement of their own; rather, they were to fan out across the country and use their knowledge to boost agriculture as a whole. Furthermore, any assistance given to Jewish Kadoorie graduates would have to be matched for Arab Kadoorie graduates, entailing an expenditure beyond its means. In general, there were little available land, and the government preferred to place what there was at the disposal of the JA to use as its discretion.43

Amos Brandsteter did not sign the application. He knew very well that he would be returning to his father’s farm in Yavne’el. Not so Allon. His memoirs say that he entered into the plan half-heartedly.44 Nevertheless, his signature was the first step in his break with Kefar Tavor.

Kefar Tavor may have been home, but certain aspects of it caused him distinct discomfort. He never invited any of his friends to his house. Not even Ada ever crossed the threshold. If a friend happened to accompany him on his way home, he made sure that he did not come inside but waited for him outdoors. He seems to have been ashamed of the poverty, which is strange since poverty was not looked down upon, especially not in his circles. Ada was puzzled by his behavior: true, her own family occupied a fine home at the time, and her father earned the enormous salary of Palestine £500 a year, but this was one period in a long life that had known hardship and struggle. For Ada, poverty carried no social stigma. This was not so for Allon: he regarded it as a blot, as something to be hidden.45

Perhaps, it was the shabbiness, not just the poverty, that accounted for his attitude. The house was run down, having gone without a woman’s touch for years. Rickety walls stood unrepaired, no ornaments or luxuries of any kind graced the premises. Within these bare walls, there lived an old man and a boy. Allon’s home was not like any of those of his friends, not even the poorest among them.

Since Kadoorie, he saw Mes’ha with different eyes. Compared with Ada, its plain, simple girls held no charm for him. Compared with the modern agriculture he learned at Kadoorie, Mes’ha’s farming methods, including his father’s, appeared terribly backward. Even the local school, which he remembered fondly and had built up before his new friends, had lost its luster.

Allon, in Bet Avi, attributes his leaving Mes’ha primarily to the ideological changes in him during his second year at Kadoorie: “The ideological consideration began to vie within me with natural sentiment,”46 “the social-moral uniqueness of kibbutz life; the qualitative standard of living; equality and mutual responsibility” were values that drew him with magic strings to the concept of the kibbutz, he said. “From day to day, I became increasingly convinced of the justice of the kibbutz way for the Yishuv, the nation and human society, and from day to day my desire to belong to it grew.”47 Was this really the case? Ideology was not discussed at Kadoorie. Among themselves, the boys would prattle on about soccer, girls, security actions. The question of a kibbutz composed of Kadoorie graduates came up only in their last few months. But it was not an intellectual conviction, merely the way of life favored by the country’s top youth. Few of Kadoorie’s graduates had been exposed to the enriching food for the soul served up by youth movements. They lacked the values education absorbed by members of youth movements. In this sense, there was very little difference between the youth of Maccabi Ha-Tza’ir and the youth of Ha-Noar Ha-Oved at Kadoorie. The latter’s onsite activities amounted to twice yearly visits by a movement coordinator. The socialist-Zionist bricks that built the ideological foundation and motivation for kibbutz life were not inherent in Kadoorie’s cultural world.

Allon grappled with the decision in talks with Ada and even more so in his letters to her. He seemed to find it easier to express his reservations in writing. Unfortunately, the letters have been lost, but their substance was clear enough and confirmed by the accounts of his friends. Ideology played a marginal role. The decisive factor was his feeling that Mes’ha was a dead end; a curtain on the new horizons he had glimpsed since coming to Kadoorie. A return to Mes’ha was a life sentence of retrogression, of poverty without compensation or challenge, in a backwater marginal to the great drama unfurling in the country. Apart from his sense of guilt at abandoning his father—and shattering the old man’s hopes that the child of his old age would carry on the family farm—Mes’ha did not beckon him.

The kibbutz, in contrast, symbolized the new world: the company of young people, a hazardous location, a tractor instead of a plow, creating something from scratch. More than an explicit worldview, it was a proclamation of belonging to a dynamic current, to the Yishuv’s creative forces at the time.

There was also the question of his future relations with Ada. Ada had finished the Re’ali School and was also considering her next move, whether to go to a university and study literature or join Allon on a kibbutz. Two things were clear: she would not go to Mes’ha and he would not pursue further studies. But going to a kibbutz together was an option. In the end, Ada chose to study at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. It was the termination of their four-year relationship.48

The decision to leave Mes’ha and the Paicovich farm was very difficult for Allon—comparable, perhaps, to the decision of Diaspora youngsters to quit home and country and make aliyah to the land of Israel. It spelled rupture with a wealth of loyalties: childhood landscapes, the land and the farm, the father who nursed hopes and had expectations of him. Like pioneering aliyah, it was a new start and complete break, clean, clear-cut, life defining. It molded his life, but also his father’s—for there was no one left to shoulder the burden of the farm now, and Paicovich was seventy. The choice was between Allon’s life and his father’s. At that moment of hard—even cruel—truth, the nineteen-year-old Allon found the strength to opt for the future.

The meeting at which he announced his decision to his father must have been one of his greatest trials. According to Allon, Paicovich told him that he had the right to do as he saw fit—even if he had not consulted his elder. But by saying that he, Paicovich, would go on living at Mes’ha, the lonely old man saddled Allon with a heavy sense of responsibility for his father’s fate.49 Emotional blackmail comes in many forms and is not necessarily direct. Paicovich may have hoped that Allon’s decision was not final, that he would think better of it and return to Kefar Tavor.

A chain of events now conspired to turn Allon’s intent into fact. Paicovich took sick and Allon had to hospitalize him in Haifa, near the home of his daughter, Deborah, and her family. Allon meanwhile stayed on at Mes’ha, having promised his father that he would not go to a kibbutz until the summer farm work was done. After the reaping, threshing, and storing of grain, he was faced with a dilemma: his father was in a hospital in Haifa, where the family wanted him to stay, with or near his daughter or one of his sons. Allon was all alone on the farm and the farm was a yoke around his neck: a homestead with livestock and poultry could not be left for a single day. It was one thing to talk about leaving, another to actually do so when there was no one else to take over. That summer, lonely and in a ramshackle house, he was more conscious than ever of the noose his father had placed on him. He was suffocating. In this mood, he decided that if he wished to live, he had no choice but to dismantle the farm and sell off the inventory. Only a draconian measure could free him of his native village. Only thus could he be the master of his fate.

It was a daunting decision, likely fueled by desperation and the typical egoism of the young. His mind made up, he acted quickly, feverishly. Livestock, poultry, wheat—everything was sold off. Every cow he let go added to his sense of freedom. In the end he was left with a pair of mules, a year’s feed of barley for them, and a wagon. He harnessed the mules to the wagon, loaded the feed, and set out, a man alone on the perilous roads of Eretz Israel in the summer of 1937.

He headed for Netanya and his brother, Zvi. He had done his calculations. He figured out that if Zvi were to hire out the wagon and mules for work in Pardes Hannah, the earnings would allow Reuven Paicovich to live comfortably. After spending the night at Kefar Hasidim, Allon and his wagon arrived in Haifa in the morning. He sped to the eastern train station where his brother Eliav worked, only to be reprimanded: how had he taken it in his head to make the dangerous trip from Kefar Tavor to Haifa?! But this was nothing compared with Eliav’s fury when he heard what Allon had done. Beside himself, he ran to get Moshe, the eldest brother and his superior on the railway. Allon now felt the wrath of both brothers. How dared he, without consulting anyone, eradicate the toil of decades at a single stroke? Worse still, Reuven had to hear of it while hospitalized. Allon chose to let his brothers inform their father. He took the mule wagon and continued along the coastline from one brother to another, from Mordekhai in Binyamina to Zvi in Netanya, being met everywhere with shock and rage. The further he journeyed, the more the magnitude of what he had done sank in. He was terrified by the thought of the inevitable encounter with his father. But Paicovich’s reaction was surprisingly mild. After hearing what Allon had done, he was silent for a moment. Then, he turned to his sons: “And you let him travel alone in these times?”50 By the time Allon came to visit, Paicovich had no scolding or preaching for him. Whatever anger he may have felt succumbed to relief that the boy was unharmed, despite his rashness.51

Neither his brothers’ fury nor fear of his father’s reaction made him regret the deed: by selling the farm he had purchased his freedom, and nothing equaled his sense of liberation. He dispensed with self-reckoning; it had been a campaign for his own self opposite his father’s great shadow. And, as in every campaign containing an Oedipal component, Allon emerged with a sense of victory mingled with guilt. In time, the guilt produced Bet Avi. The triumph produced Yigal Allon.