Читать книгу Yigal Allon, Native Son - Anita Shapira - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1

Mes’ha: The Beginning

When Yigal Allon, born Paicovich, reached bar mitzvah age, he, like all the boys at Kefar Tavor/Mes’ha, was called up to the Torah. Yet the ritual merited no mention in his memoirs. Instead, he recorded the test of courage his father put him to that day. Yosef Reuven Paicovich—known by all as Reuven—summoned the boy to the silo and said, “By putting on phylacteries you still do not satisfy all the main commandments; today, you are a man and, from now on, you will have your own weapon.”1 With these words, he handed the boy a semi-automatic Browning.

Allon could not contain his excitement. But there was more. That night, Reuven sent him out to guard a remote field on the colony’s northern edge. Known as Balut in Arabic, Allon in Hebrew, after its oaks, the field abutted the convoy route from Transjordan to the Mediterranean. To reach it, Allon had to walk some five kilometers. He arrived at about 8 P.M. with fear as his constant companion: it was his first stint of guard duty on his own. He took cover amid rocks and oak trees, starting at every sound and rustle in the fields. He fervently hoped that the robbers would rest from their labors this night, but it was not to be: just after midnight a passing convoy came within earshot. He saw three men get off their horses and start stuffing sacks with the sorghum that had been gathered. Reuven’s instructions had been very clear: should thieves come, Allon was to let them go about their business at first; then, he was to call out warnings in Arabic and, then, shoot to miss in order to avoid escalation. He was permitted to shoot to hit only if they drew near. Allon recounted: “I followed all the instructions. I got over my fright. And Father’s orders too made sure [that I would do] as I was told.”2 Far from being alarmed by Allon’s calls, however, the bandits dug in and returned the battle cry. Allon shot into the air; he was answered by the cocking of guns. He had no instructions left, and his thoughts came hot on the heels of one another: Should he shoot to hit? Should he flee under darkness? What if he hit one of them? What if he himself were hurt? All at once, help materialized. His father came storming in from the side, spitting and spewing curses in heavily accented Arabic and firing above the robbers’ heads. Just like in a western, the robbers jumped onto their horses and made off. Yigal Allon summed up: “My joy was double that night: not only did I meet the test, but Father saw me do it. I can’t imagine how I would have looked him in the eye had I not acted as I did.”3

It was a rite of passage in a frontier community where all adult men carried arms. Initiation into male society demanded proof of courage, symbolizing a value system imparted from father to son. Reuven Paicovich may have had a greater dose of courage and belligerence than his fellow villagers, but this does not diminish the transformation that had taken place in the value system of Jewish men who had settled the wilds of Galilee only twenty years earlier.

Yigal Allon was born in a small village at the foot of Mount Tabor and spent most of his first twenty years there. His early experience, as seen through the eyes of a boy, was described in Bet Avi (My father’s house): it was a world of intimacy with the land, of the fragrance of baking bread, of the delights of the threshing floor on a summer night, of neighborly squabbles and brawls, of tests of courage and displays of physical prowess. The village depicted by the adult Allon was bathed in the magic that maturity lends to childhood. The farther he wandered from Mes’ha, the more his descriptions benefited from the distance of time and place, toning down imperfections and enhancing the charm of his salad days.

The Paicovich family saga began in Grodno, White Russia, at the crossroads between Vilna in the north and Bialystok in the south. Its Jewish community, one of the most important in Lithuania, dated back to the twelfth century and had produced scholars and sages.4

The saga opens with Yigal’s grandfather, Yehoshua Zvi Paicovich, in the second half of the nineteenth century.5 Earlier generations were apparently unremarkable, and certainly not scholarly. The Paicoviches were a family of means. Yehoshua was a builder; his wife, Rachel, managed the family hardware store.6 Reuven entered the world in 1873, a year after Shmuel, the firstborn. As a child, he was drawn to “un-Jewish” pastimes: roaming the fields, dipping in the waters of the Niemen River, climbing a tree. He was especially fond of animals and secretly kept a dog and a cat in the attic despite the Jewish ban on pets for reasons of impurity. Often enough, his exploits earned him the feel of a fatherly thwacking.7

In 1890, Yehoshua decided to move to the land of Israel with the two older boys, Shmuel and Reuven; according to family tradition, he was a devout adherent of the Lovers of Zion movement. Additionally, his boys were now of conscription age in White Russia, and he had no intention of offering them to the czar’s army. Some citizens of Grodno had immigrated to America, but Yehoshua set his sights on Palestine.8

It was a ten-hour train journey from Grodno to the Black Sea port of Odessa, where ships set sail for Palestine. Manning the gangplank was a towering gendarme possessed of the furry kicme headgear and a daunting sword. But he was no fool: spying Yehoshua and the two boys, aged sixteen and seventeen, he detected draft dodgers! With a stomp of the foot and thunder in his voice, he made it plain that they would not slip away. Thus spoke the figure of authority. Unruffled, the slight, unimposing Yehoshua stepped to the side and dabbed his perspiration with a handkerchief. He placidly withdrew a few rubles from his pocket and proffered them to the rampaging gendarme. It was Reuven’s first lesson in dealing with the powers that be: the man underwent an instant metamorphosis. Patting the boys on the cheek, he murmured, “children, children,” and bade them a pleasant journey to “their Palestine.”9

A week later, the three disembarked into the hustle and bustle of the port of Jaffa, where the Arab porters impressed them as aggressive and untamed, and they could not understand their cries. They headed for the Jewish colonies, finding work in the vineyards of Rishon Lezion, Rehovot, and Nes Ziona. Mostly they turned over the earth and prepared it for planting with the help of a hoe. For a day’s hard labor, they earned seven Turkish pennies, barely subsistence money. It is not clear how long they were so employed: one account indicates two years; another, only a few months.10 In any case, they were soon known as hard workers, and Yehoshua Ossowetzky, a former agent of Baron Edmond de Rothschild in Nes Ziona who was now in charge of Jewish settlement in the Lower Galilee, invited them to the newly founded colony of Rosh Pinnah. Paicovich’s building skills could be put to good use there, and they accepted with alacrity.

From that day on, the Galilee was Reuven’s home. The hilly landscape spellbound him. Mount Canaan beckoned him. Within days he had scaled to the top, a curious act in the eyes of the residents of Rosh Pinnah, who felt little urge to commune with nature. He spent several years building Rosh Pinnah and dreaming of farming: of obtaining a tract of land from the baron or the Jewish Colonization Association (ICA).

The dream remained out of reach. Meanwhile, he made a name for himself as a valiant young man, and the matchmakers took notice. In his words, “a meeting was arranged, she liked me, I liked her and, in time, I was married to Chaya, daughter of Reb Alter Schwartz, of blessed memory, and set up home.”11 This depiction may have done for Reuven’s time and society, but it was too prosaic for his sons. They wanted romance. And in their rendering of the parental encounter, Reuven spied a caravan of donkeys descending from Safed to Rosh Pinnah; mounted on one of them was a black-eyed maiden who immediately lit his fire.12 This biblical portrayal is the version that became ensconced in the family saga. One way or another, in 1894 Reuven Paicovich and Chaya Ethel Schwartz were wed.

Chaya came from an old Safed family. Her mother was the granddaughter of the rabbi of Buczacz, a source of pride for Chaya. The family tradition holds that the family had lived in Safed since the Middle Ages; one branch had departed for Buczacz and service in the rabbinate, though following generations had returned.13 Reb Alter Schwartz, Chaya’s father, was one of seventeen young, married yeshiva students to join the pioneer Elazar Rokeach in the establishment of a new farming village. The group purchased land from the Arab village of Ja’uni for what became the Jewish Gei-Oni.

Gei-Oni was plagued by drought, and the colonists lost their assets. In 1882 a Lovers of Zion delegation from Romania toured the country to acquire land for settlement. Captivated by the vistas of Gei-Oni, they bought out the first settlers. Four of the original families refused to sell and joined the Romanian group,14 which renamed the site Rosh Pinnah. One of the four was Reb Alter Schwartz. He, however, soon sold out to the baron, served a two-year rabbinical stint in Alexandria, and, upon his return, began to work for the baron as a supplier, a position he retained until his death. Chaya was his firstborn.15

Reuven and Chaya lived with Reb Alter for some five years, producing two sons during that time, Moshe and Mordekhai. In 1898, construction began on the new colony of Mahanayim, near Rosh Pinnah. Reuven was asked to lend his building skills and guide the newly arrived ultra-Orthodox immigrants from Galicia in the ways of the land. In return, he hoped to obtain a property at Mahanayim and finally settle down to farming. He gave three years of his life to Mahanayim, built a house, invested every penny he managed to save from working at the site, and brought his wife and children to live with him.

But the Lovers of Zion movement that backed the project suffered serious financial and social setbacks. In 1902–3, Mahanayim was abandoned and its lands were ultimately annexed to Rosh Pinnah.16

Reuven found himself back at square one: out of pocket, out of work, thirty years old with a wife and three children to support (a third son, Zvi, had meanwhile joined the family). The future looked bleaker than ever. In 1900 the baron handed over the administration of his colonies to the ICA. The First Aliyah wave of immigration to the land of Israel was in crisis, having lost faith in the enterprise. Farmers of the relatively sound, orchard-based Jewish colonies on the coastal plain upped and left the country by the dozens. Many in Palestine’s new Jewish Yishuv lent an avid ear to the Uganda Plan (the idea of establishing a Jewish colony in East Africa under British protection), for who knew better than they how arduous it was to settle the land of Israel. Reuven decided to try his luck in America, the “goldeneh medineh.” His decision, in 1905, stemmed from a sense of impasse and despair. Should he get on his feet in the United States, he planned to bring his family across. Should he fail, he would return to Palestine. His conscience would at least be clear that he had not missed the opportunity of a lifetime.17

He shared his plans only with his wife, who was once again with child. He divided the little remaining money from Mahanayim into two: half for Chaya and the children, who stayed with her father; the other half for himself. Early one morning he rose, mounted a donkey laden with bags, and rode it to Beirut. From there, he sailed to Marseilles and then on to the United States. Three weeks later he disembarked in New York.

America did not smile on Reuven. He found life on the Lower East Side alien and longed for open, star-studded skies and green fields. He was a diligent laborer earning adequately for the times. But he made no real money. What he did manage to put aside, he referred to as kishke gelt—whatever his gut could spare. After two years, he returned to Palestine. America had turned out to be a false dream.18

Left with no alternative, he swallowed his pride and applied to the ICA for a leasehold at one of the Lower Galilee settlements under development. He explained his inclination for manual labor, his aspiration to live off farming, his yearning for the soil. The officials—as he told it—not only agreed to settle him but even allowed him to choose one of four sites. But when the time came to make good on the promise, Rosenheck, the ICA clerk, reneged on the offer and directed him to Mes’ha, that is, Kefar Tavor.19 Whether fact or fiction, the incident marked Reuven with a life-long hostility toward ICA officials.

It was not a choice area for farming and settlement. The Eastern Lower Galilee gets little precipitation, and natural springs are few. The harsh conditions had driven most of the Arab villagers out in the nineteenth century,20 and the region was overrun with marauding Bedouin. Force was the law of the land. Tribes arbitrarily fought one another, provoked the Ottoman government, and mercilessly attacked village after village. By the close of the nineteenth century, even the most optimistic estimates put the entire population there at only tem thousand.21

In the nineteenth century, destitute peasants were crushed by loans they were unable to repay. Lands slipped out of the hands of cultivators and into the hands of capitalists or the government. The southern part of the Eastern Galilee became state land and was purchased by Sultan Abed al-Hamid; the northern part was taken over mostly by wealthy effendis from Nazareth, Acre, Damascus, and other places. Here, then was an opportunity for Jewish settlement agents to acquire sizable tracts. The largest Jewish land-buyer was Baron de Rothschild. His agent, Yehoshua Ossowetzky, picked up 30,000 to 50,000 dunams (7,500 to 12,500 acres; 3,000 to 5,000 ha) from an Arab living in Syria. These transactions took place in the 1880s and 1890s. Jewish settlement in the area began at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth.22

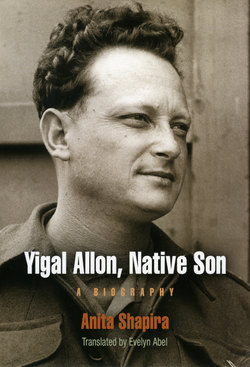

Figure 1. The Paicovich family: mother, Chaya; father, Reuven; and three sons: Moshe, Mordekhai, and Zvi. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Allon family.

Jewish settlement of the Eastern Lower Galilee was associated with the transfer in 1900 of Baron de Rothschild’s villages and assets in Palestine to the ICA. Founded by Baron de Hirsch in 1891, the ICA aimed to ease the lot of Eastern European Jews by promoting their agricultural settlement around the world, particularly in Argentina. Unconnected to Zionism, it wished to see Jews emigrate and become “productive.” On top of his holdings, Rothschild gave the ICA more than 15 million francs to help set Palestine’s Jewish villages on a firmer footing. The ICA opened up a new department to deal with agricultural settlement in Palestine.23

Rothschild’s move angered and alarmed the colonists. Mainly, he was motivated by the colonies’ stagnation: after eighteen years of hard work and huge investments—estimated at £1.6 million—they were still not self-sufficient. The transfer of their administration to the ICA signaled a new approach. The ICA stopped subsidizing wine, which had artificially raised income; vineyards were uprooted for lack of demand and other crops were introduced. And settlers were allowed far more autonomy in the internal management of village affairs. In the space of a few years, the colonies were at long last self-sufficient and even enjoyed a measure of ease. They grew and prospered during the Second Aliyah immigration wave of 1904–14.

In the Lower Galilee, the ICA hoped to solve the problem of landless farm laborers and second-generation farmers by inaugurating a relatively cheap form of settlement. In the first decade of the twentieth century, it founded six villages: Sejera, Kefar Tavor (Mes’ha), Yavne’el (Yemah), Bet-Gan, Melahamiya (Menachemiya), and Mitzpeh. Rothschild, in the veteran settlements, had been guided by the model of a European village based on sophisticated agriculture and run by comfortable or wealthy farmers. The ICA envisioned a modest village where the farmers earned their bread by the sweat of their brows.

The crops chosen for the Lower Galilee were those better suited to dry farming. Because income was expected to be relatively low, each unit was enlarged to 250–300 dunams (62.5–75 acres; 25–30 ha). In the opinion of the ICA, a plot of this size could support a family even if it were farmed extensively.24 The ICA provided the plot, undertook to build the homestead, and extended a loan for the purchase of animals and equipment: plows, wagons, seeds, oxen, and so forth. In return, the settler undertook to cultivate the entire unit with the help of his family, using hired labor only in high season. From his own pocket, he was to handle land amelioration, irrigation installations, and (road) infrastructure. He received the unit on lease and was to pay the ICA 25 percent of the harvest as did tenant farmers in Arab villages to their landlords. The loan was to be repaid gradually. The ICA transferred title only after years of trial and proof of aptitude for farming. The system of tenancy made it possible to settle people with no means of their own at quite a low cost; at the same time, the settlement company retained the leverage to make sure that a farmer honored his commitments and cultivated the land made available to him. Settlers not up to the task could be evicted and sometimes were.25

Reuven’s allotment was at the foot of Mount Tabor, a domed peak towering over the region in splendid isolation and casting its shadow over the small village on its eastern flank. Graced by a dense oak woodland (later sacrificed for fuel by Arab villagers), it boasted two monasteries (one Catholic, the other Greek Orthodox), and appeared mysterious, even ominous. Kefar Tavor was on the ancient Via Maris from Egypt to the Fertile Crescent. Straddling the gateway from the Lower Galilee to the Jezreel Valley, it was in a strategic position.

The pristine scenery could not disguise Mes’ha’s sorry location on a thirsty ridge of the Eastern Lower Galilee.26 Children may have taken great pleasure in the dry wadis and ruins around the colony,27 but the basic water shortage went unsolved. It was the chief cause of Mes’ha’s troubles, misery, and sluggishness, and frequent drought only made the situation worse, damaging crops and drying up springs.

Reuven Paicovich and his family were not Mes’ha’s first settlers. The colony was established in 1900 and its early founders—some twenty-two in number—had included two groups: first- and second-generation farmers from Metullah and Rosh Pinnah, tough Galilee rustics who made do with little and had already tasted frontier settlement; and the offspring of orchard colonists from Zikhron Ya’acov and Shfeya, who were considered more pampered by the farmers mentioned above. The guiding principle behind the ICA’s choice of settlers was fitness for farming and prior experience. Many of the settlers already had families, although some were single. They did not know one another beforehand and antagonism soon developed between the groups from Galilee and Zikhron: everyone wanted the derelict huts at the site left over from the abandoned Arab village, and there was no end to quarrels and resentment. The same was true when it came to the allotment of fields. In short, Kefar Tavor’s members were known as hotheads, a “title” they did everything in their power to defend.28

The village was laid out in the usual cross: a long street lined on both sides by a row of houses with red tile roofing from Marseilles. This street was bisected by a shorter street, perpendicular to the farmers’ houses and containing the public buildings: the synagogue, the school, the teachers’ houses, the doctor’s house, and the council premises. Every home was fenced off and backed by outbuildings: a stable, a barn, a chicken coop, a tool shed, and a shack for the Arab hired hand and his family. A defensive stone wall ran along the rear of the farmyards to protect the homesteads from marauders.

It was not a welcoming community: “In this small, this tender body, so much strife, conflict, and carping,” an item in Hashkafa described Mes’ha, “happy faces and laughter—no way.”29 On its third anniversary in 1903, Mes’ha was crowned with the Hebrew name of Kefar Tavor by the visiting Zionist leader Menachem Ussishkin.30 The settlers persisted with the old name. It was partly one, partly the other: a failing village patterned after the old Arab format; a Jewish colony striving to belong to the new Hebrew Yishuv.

In those early years of real pioneering, stark hardship, and a gnashing determination to gain a grip on the Lower Galilee, one of Mes’ha’s residents was Joseph Vitkin, a precursor to the Second Aliyah and the principal of Mes’ha’s school for two years. His letters are filled with an unmistakable wretchedness, even if we discount personal circumstances, physical infirmity, and loneliness, severed as he was from any living being he could talk to. The letters reflect Mes’ha’s young face: a poor, miserable village that drowns in mud and is cut off from the world with the first rain. “I detest these crude and alarmingly rotten surroundings, to an unbelievable extent,” Vitkin wrote.31 Vitkin’s attempts to inject a mood of nationalism in his pupils and even in the farmers of the colonies by appealing to voluntarism and the general good were met with bitter derision: how easy it was for him, who could be sure of his meal, to preach idealism and making do to people who worked themselves to the bone and went hungry for bread.32 The high-brow Vitkin found no common language with the farm workers whose children were his educational charges. He felt that he failed to leave a mark on the children: “The environment is stronger … and all that we sow within the school walls in the long term and with great emotional effort is uprooted in the short term.”33

Mes’ha was synonymous with dereliction. When the teacher Asher Ehrlich and his wife, Dvora, arrived at Mes’ha in 1905 to replace the exhausted Vitkin, they found twenty-two abandoned houses, the tenants having returned their homesteads to the ICA. Some of the houses—recently built—were already cracked and dilapidated. In the entire village, there was not a spot of green—no grass, no flowers, no fruit trees. These were luxuries ruled out by the lack of water. But, in any case, the population did not have a feel for ornamentation or a need to introduce beauty into their lives. In this respect, Mes’ha resembled the Eastern European shtetl where Jews did not hanker after aesthetics, especially in public areas; aesthetics were a trivial goyish pursuit of non-Jews.34

Vitkin, in one of his letters, bemoaned the hills of Mes’ha that closed in on it and robbed it of a horizon, of open space. But Mes’ha’s residents were quite comfortable with the narrow vistas handed them by fate. In time, those who stayed on despite the privations very likely explained their endurance in Zionist terms. The romanticism of their twilight years lent an aura of idealism to the ordeals of youth and maturity. If truth be told, however, their aliyah to Eretz Israel had been a combination of love of Zion—the fruit of midrash, aggadah, and liturgy—and the hope of a better living in Palestine. The tidings that Baron de Rothschild was settling Jews on the land and that other agencies too were involved in the endeavor attracted Jewish immigrants to Palestine. Yet they were a mere trickle. The great current flowed toward American shores. There is no way to quantify or appraise the ratio between emotional nationalism and personal expediency in the hearts of those who turned to Zion. Often, those guided by expediency lost their hearts to the country and never were to be dislodged from it, not even by a dozen oxen, while those who came in search of King Saul’s Hills of Gilboa or Gideon’s Ein Harod broke on the rock of reality, abandoning the country of their dreams in disillusionment. Of Mes’ha’s residents it may be said that their Zionism came after the fact and despite everything; they certainly paid a high price for their Eretz Israel.

To the extent that they ever had dreamed of the country and their lives in it, the dream had been as narrow as their village horizon: to dwell each under his vine and fig tree in the Promised Land. They had no problem with the traditional lifestyle of the shtetl. Religion played a central part, molding individual and public spheres. Kashrut was self-evident, and everyone attended synagogue on the Days of Awe. Only the doctor was allowed to absent himself since, as everyone knew, he was well-versed in external wisdom and therefore exempt from the rules governing ordinary Jewish mortals.35 In principle, Mes’ha’s inhabitants did not suffer from overeducation. As was typical of a Jewish shtetl, those with schooling consisted of the teacher, the doctor, and the pharmacist, although not in all cases.

Mes’ha was a mirror of the faults and virtues of a shtetl: arguments and intrigue were regular fare, and the infighting in some years caused the council to change its composition more than once. Yet, there was also a sense of mutual concern: when disaster struck—a householder’s death, lengthy illness, and so forth—the council would strive to extend assistance while the women lent a hand with housework and everyday needs. Men, too, could rise to gestures of magnificence, plowing or sowing a neighbor’s fields. In normal times, though, every farmer jealously guarded his own acreage and kept to himself.

The move of Mes’ha’s residents from the shtetlach or villages of their births to Kefar Tavor did not entail modernization, a new self-image, or a new worldview. But when an Eastern European Jewish village is planted in the Wild West of the Palestine frontier something’s got to give. The Lower Galilee sprouted a frontier culture complete with romance, symbols, and heroes, with its own lifestyle and code of conduct. The Paicoviches fit right in.

In November 1908, Reuven signed a contract with the ICA and became a tenant farmer on the lands of Um-J’abal—“the mother of mountains” in Arabic.36 The best fields had already been taken. Newcomers were given remote plots, several kilometers to the north of the village, on the lower slopes of Mount Tabor (at the site of today’s Kibbutz Bet Keshet). The virgin soil was so stony in parts that the earth could not be seen. It bordered the lands of a-Zbekh, the strongest, most dangerous Bedouin tribe in the area. The Zbekhs claimed ownership of some of Um-J’abal, while the ICA had plans to extend its holdings into a-Zbekh’s territory. Thus, tension over land was already in place, even before anyone took a hoe to the ground.37

Paicovich’s field neighbors too were recent arrivals. One was a Yemenite Jew named Zefira; the other, Mattveyov, was one of the Russian converts to Judaism who settled in the Galilee. Come the rainy season, the three planned to plow their fields together. But the route to their fields passed through a-Zbekh territory and the tribesmen blocked their way. The farmers thought they might outwit them: they tried their luck at dawn, they tried in the middle of the night, but it made no difference. Whenever they showed up, the Bedouin were out en masse to greet them, until one day Reuven’s patience snapped. Booming with rage, he demanded the right of passage. Seeing that this made no impression, he drew his rifle and fired into the air. He had every intention of continuing to shoot when he noticed that one of the elders wished to approach. Reuven was too angry even to listen at first, though in the end he heard the Bedouin out—from a distance. The tribesman informed him that from now on the a-Zbekhs would accept them as neighbors and allow them through. Paicovich’s reputation was sealed. From then on in a-Zbekh eyes, he was brave and indomitable. Sipping cups of coffee, they wondered who he was. A Jew? Certainly not: Jews were walad el-mitta (mortals), that is, cowards who did not defend themselves. A Muslim or a Christian? Evidently, no. Ultimately, they concluded that he was an Insari, a member of the north Syrian tribe of Ashuri known for their courage. Paicovich’s sons adopted the appellation. At family affairs, he became “al-Insari” to them.38

Paicovich threw himself into farming with all the love and energy of a man who had at last realized his life’s dream. With infinite toil, rudimentary tools, and no mechanization whatsoever he cleared his fields stone by stone and used the stones to mark off his land. He actually enlarged his holding to 350 dunams (87.5 acres; 35 ha), a takeover that won recognition from the ICA.39

His love for the soil was almost sensual. As if born to farming, he would pick up a clod of earth and relish its taste. Every stalk of grain fallen from the wagon he retrieved with a loving hand. He had his children or a laborer trail behind the wagon to collect whatever fell off—a practice that his neighbors variously interpreted as either mingy or thrifty.40 Meticulous and orderly, he took great care of his tools and his harvests. The rows he sowed were painstakingly straight. The olive grove he cultivated had no match, and his vineyard earned high praise from visiting ICA officials who marveled at the talents of the novice farmer. He raised potatoes in his vegetable garden and, by his own account, every potato that he managed to grow was treated with the reverence Jews reserved for a perfect citron.41

Paicovich was known in Mes’ha as a smart farmer adeptly managing his holding. Industrious, persevering, and surrounded by a bevy of sons learned in the lore of the land from the cradle, he had the advantage over his neighbors. What’s more, he was tall and strong, and took easily to physical work. A hard and stubborn man, he could hold his own in negotiations. As a result, the family was not counted among the colony’s poor. Poverty and wealth, however, are relative concepts.42

Life revolved around work. Chaya rose in the wee hours to do her chores and to prepare food for the field hands. She would rouse the family and, at first light, Reuven would set out with the boys. They were not seen again until nightfall and, sometimes, especially during harvest, they continued working past dark. After the day’s work, the boys would hitch a wagon and ride to the spring to fill barrels of water for drinking and household needs. The houses in Mes’ha had no running water until the 1930s and trips to the spring were a daily ritual. Alighting at the source, the boys would lower a can into the water, fill the barrels, and carefully cover them with sacks to protect the water from road dust. At home, again with great care, they would empty the barrels into vats kept in the farmyard. The route to the spring cut through fields with bumps and potholes, and on occasion the barrels arrived home half-empty. The spring could not supply the colony’s demand and in drought years—which were frequent—it would be dry by summer’s end. Its waters were turbid; as soon as several farmers had drawn their fill nothing remained for the rest. The water level was on everyone’s lips as farmers passed one another to and from the spring.

Water was a source of friction with the Arab neighbors too: in periods of drastic shortage, Mes’ha’s young would get into fights trying to pilfer water from guarded Arab wells. Water wars were an annual occurrence. Two Mes’ha boys were once caught red-handed yet continued to draw water rather than flee. Finding themselves surrounded, one of the boys shot into the air, mustering the entire colony to their rescue. Before matters could escalate, a soft-spoken teacher by the name of Entebi stepped in and rebuked the Arabs; he shamed them for their un-neighborly behavior, depriving the thirsty colony of drinking water.43

In these conditions bathing and laundry were obviously a luxury, particularly in summer. For decades, this was the situation at all settlements in the Lower Galilee. It is little wonder that one girl from Yavne’el carried a lifelong memory of an immaculate first-grade teacher with not a fly on her, while clusters of insects hovered over the children’s faces.44

Life at Mes’ha followed the agricultural cycle and seasons: in the autumn, everyone looked out for the first rains. When they came, the land was prepared for sowing. Oxen were used for plowing until they were replaced by mules in the transition from the light Arab plow to the European kind.

In winter, the village was totally cut off and enveloped in heavy mud, inside and out; no one arrived, no one left. Roads were unpaved and a journey to Tiberias or Nazareth could not be made without a donkey. Later, under the British Mandate, the outside world was opened up by train service from Afulah. The rainy season was a time for repairs. Housewives used the long winter nights to sew clothes for the family or to sell and earn a little extra money. Families sat around tables lit by oil lamps. The oil was imported in tins and sold by the measure, and the filling and the lighting of the lamp was an art in and of itself: if a lamp died out, the children were generally charged with relighting it, taking care not to get burned by the hot glass.45 On nights such as these, Reuven Paicovich would read to his children from Hebrew literature: Abraham Mapu, Peretz Smolenskin, Mikha Joseph Berdyczewski, I. L. Peretz.46 Winter was also the season for studying since in the spring and the summer children twelve and older would accompany their fathers to the fields, making up school assignments in the evenings after a hard day’s work.

Spring was heralded by the return of Mes’ha’s cattle to the village. Spare in flesh and produce, the herd consisted of Arab cows unflatteringly known as “tails.” In winter, when a thin mantle of green covered the hills, Arab cowhands would lead them to pasture north of the colony—“on vacation” according to the local jesters. Two months later, the cows came home, filling the air with mooing and lowing as each found its way to its master’s yard and every farmer spotted his beast.47

Summer’s sign was the threshing floor: the entire family with the exception of the farmwife would scramble to bring in the grain out of harm’s way, be it from natural or human elements. To guard the harvest from thieves, everyone slept in the granary. Girls and young women brought along food and drink, someone would reach for a harmonica, and the sound of song would soon be heard. Couples seeking privacy clambered to the top of the piled-up sheaves, away from prying eyes.

Mes’ha may have been lean, but it did not suffer from hunger. Most of the food was home grown. The seeds from the harvest were ground at the Kafr Kama flourmill, which worked like a charm, unlike Mes’ha’s contraption. For the children, the walk to Kafr Kama, a Circassian village, was like a holiday: in addition to the half day off from work, there was the anticipation of waiting in line for their turn at the mill, of buying sweets for a penny, of roaming through the narrow village lanes—all of it was a lingering adventure.48

For cooking and baking, the Arab outdoor tabun was used. The first settlers to arrive in the Lower Galilee had erected the usual barred range, but the lack of wood for fuel soon posed a problem, while rising smoke made housework grueling. Into the breach stepped the wife of the harat, the Arab laborer: kneading together grass and earth, straw and water, she marked off a tabun in the ground to present the women with a superior technical upgrade. It was fueled three times a week with the help of slow-burning, kneaded animal droppings, but since matches were not always handy, great care was taken to keep the embers alive. The tabun became hearth and home.49

The food was simple and natural: bread, milk, cheese, and butter. Eggs from the chicken coop were plenty and were often sold to a wholesaler in exchange for such luxuries as herring or halva. Cooked food was based on cereals and legumes: bulgur, cholent, and so forth. Meat was less common, although for the Sabbath and holidays a hen would be slaughtered. Fruit and vegetables were bought from Arabs hailing from the water-rich Bet-Netofah Valley who made the rounds of the villages. Mes’ha’s vegetable patches yielded only herbs, onions, and sometimes a potato.50

In times of trouble, the hardships of living in an out-of-the-way village were all too palpable: if illness struck, the bumpy wagon ride to a hospital in Tiberias or Nazareth could well hasten a patient’s end. In winter, the trip was out of the question altogether and the sick simply had to cope on their own. For childbirth, the bobbeh or midwife was called in—she was a Mes’ha institution in herself.

The village was too small to support good services. It had no store worthy of the name, medical treatment was poor, and the school left much to be desired. Rosh Pinnah, in contrast, was already a small town boasting various service providers from artisans to ICA officials, as well as farmers. The service providers were able to maintain a store and their presence lent the colony a sense of relative ease.51 Mes’ha had none of these.

Predictably, Mesh’ha’s relations with its Arab neighbors were complex from the first. Although the interaction was rather simple and unsophisticated, at the same time, it had many aspects: hostility was tempered by affection, dependency by self-sufficiency, aggression by friendship, and distance by closeness. Mes’ha’s attitude stemmed neither from ideology nor politics; largely, it was an extension of the attitude shtetl Jews had toward the Russian or Ukranian muzhiks who brought Jews the produce of their fields and gardens, sold them their butter and eggs, and at their stores bought the provisions they required for their farms—rope, nails, tools. The shtetl Jews’ singular attitude to the country goyim reflected both Jewish uniqueness and the Jewish anomaly: on the one hand, Jews were contemptuous of the goyishe dunderheads, who were the butt of their ridicule and deception; on the other hand, Jews had a gnawing fear of the goyim’s violent outbursts: come pogroms, all of Jacob’s wisdom would prove useless against Esau’s brawn. In Mes’ha on the whole, however, calm reigned as business dealings and interdependence spilled over onto the personal plane, sparking friendships and loyalties across national and religious divides. To a great extent, the relations between Mes’ha’s residents and their Arab neighbors were patterned along these lines.

Built on the ruins of an Arab village abandoned in the latter half of the nineteenth century, Mes’ha did not face the sort of strife that had poisoned Metullah’s early years (when the Druze claimed dispossession). It did come under attack from a-Zbekh Bedouin—though not more so than other villages, whether Arab or Jewish. Marauding was the Bedouin way of life and roving tribes had declared war on settled homesteaders. Added to this was the rivalry over water, with the wars of the herdsmen taking on biblical dimensions at times. But it was not a national conflict. Much like the Wild West where cattlemen were pitted against homesteaders, everyone did as he wished; to survive, a man—no matter how inherently nonviolent—had to learn to shoot, to fight, to ride a horse, and to defend his life, his honor, and his property.

Mes’ha’s residents drew a sharp line between friendly and unfriendly neighbors. Kafr Kama, where they sent their children to grind flour, was very friendly. The Maghreb villages whose population stemmed from North Africa were not considered dangerous. From beyond the hills, fruit and vegetable sellers came to peddle their produce. And within the village itself, each and every farmyard had a shack for the harat and his family. A harat was usually a landless peasant who hired himself out in exchange for 20 percent of the harvest. He worked alongside the farmer in any job that needed doing, plowing and sowing, reaping and threshing. His wife would spend the day with the farmer’s wife, helping with the housework, seeing to the tabun fire, washing the laundry, and doing the heavy work. Their children, too, would lend a hand and they played with the Jewish family’s children, speaking a Yiddish mixed with Arabic and Hebrew. The farmer and the harat would take their meals together in the field, tasting one another’s morsels. If a cow was stolen from the farmyard, the harat joined in the chase after the thief. During harvest, he too was recruited for guard duty. Nonetheless, the idyll was shattered at times: a harat might be suspected of pilfering from the farmer’s harvest and his wife and children “accused of” impertinence and a lack of hygiene. Quarrels could degenerate, a harat and his family resorting to violence against the farmer.52 But this show of muscle, as in Russia, was the exception to the rule; it made no real dent in the way of life. The lack of green, the smoke of the tabun, the argot of playing children, the dirt, and the neglect all lent Mes’ha the appearance of an Arab village, no different from its surroundings.

The ICA’s contracts stipulated that hired hands could be used only in the high season, and Reuven Paicovich’s contract stated explicitly that only Jews could be hired.53 It was an impossible demand. Mes’ha’s residents hailed from Rosh Pinnah, Metullah, and Zikhron Ya’acov. All of these communities, especially the last, had used Arab labor, and their former residents saw no reason to change in their new location. Besides, integrating into the surroundings meant also fostering Jewish-Arab relations. The guarding of Mes’ha was thus placed in the hands of one Hamadi, the most infamous local bandit, while harats were accepted into Mes’ha’s homes. They knew the local conditions forward and backward; they taught the farmers the secrets of the fields while their wives taught the farmers’ wives the secrets of the tabun. But this situation caused Mes’ah to have a population that consisted of more Arabs than Jews. And a niggling fear lingered among the Jews that “the Arabs would rise up one day and make mincemeat of their Jewish exploiters.”54

The mixture of intimacy and dependence often spawned true affection; some harats became part of the family, remaining loyal even through the hard times of riots and bloodletting. Other relationships ended in lifelong enmity. Unlike the colonies that did not employ Arab labor, at Mes’ha, Arabs were not strangers, not an unknown quantity. Their persons, language, conduct, and customs were part of the village tapestry; they were not foreign, but flesh of the land, integral to the landscape. The ideology of “Jewish labor” that dictated against employing Arabs created a complete separation between Eretz Israel and Palestine—in consciousness if not in actuality. The former was entirely Jewish and not overly welcoming to Arabs; the latter was Arab, a foreign land that aroused anxiety and alienation in the Jews: to them, Palestine was mysterious, ominous, intangible.

At Mes’ha, Arabs may have been neighbors or friends or even thieves, but there was nothing mysterious about them. They were real. Of course, this had no bearing on the larger picture of Jewish-Arab relations in the land of Israel, questions that were still sealed in the future, especially for people with a horizon blocked by Mount Tabor. At Mes’ha, Jewish-Arab interdependence peeled away the mystery, which, potentially, could have formed a cultural, national shell.

In this land where everyone did as he wished, the regime intervened only in extreme instances. Amid the eternal conflict between Bedouin and peasantry, law and order was to spring from the society itself. The history of the Second Aliyah reserves a fondness and place of honor for the colonies of Galilee based on field crops: they were the crucible of the independent Jewish agricultural worker, who proved capable of organizing farm work without the need of supervisors. The beginnings of the so-called Labor settlement apparently lay in the attempts and initiatives of individuals to introduce into the Lower Galilee Jewish laborers in place of Arab harats and Jewish guards in place of the Arab master thieves customarily employed. At Mes’ha, the appearance of Jewish farmhands was connected with a man who became a local legend, the teacher Asher Ehrlich.

After Joseph Vitkin despaired of himself and his pupils, he suggested to Asher Ehrlich, who lived in Rehovot, that he replace him as principal. The neglect and backwardness that so depressed Vitkin and the hills that so stifled him—these he described to Ehrlich in glowing colors, firing his idealism with a Zionist educational challenge. Ehrlich, who had been born in a Jewish farming village on the banks of the Volga, Nehar-Tov, and who had endured a four-year ordeal in the czar’s army, was tall, strong in body and soul, brave, and proud. The “long teacher”—al-muallem a-tawil, as the Arabs called him—was a walking example to Mes’ha’s youth of the need for “Jewish muscle.”

Working on the premise of a healthy mind in a healthy body, he regaled pupils with tales of Maccabean heroism and led them on excursions around the Tabor, unveiling before them the delights of Eretz Israel—its plant and animal kingdoms, its trails and landmarks—and teaching them to have no fear of Arab villagers or casual wayfarers. A chance encounter of his with Bedouin went down in the settlement’s annals: one night, while walking alone from Melahamiya to Mes’ha, he came upon two horsemen. One of them asked him for a light. Ehrlich pulled out his gun and offered him the barrel. To Ehrlich’s everlasting glory, the Bedouin fled for their lives. He was able to impress his pupils because he manifested qualities necessary for the wilds of Galilee: communion with nature, physical prowess, courage, and a proud defense of life and property. In the Wild West, decency, determination, and physical strength can triumph over the forces of evil and anarchy. This was the role Ehrlich filled at Mes’ha.55

He won Mes’ha’s hearts not only because of his personal endowments but also because he was ready to help the farmers beyond the call of duty. He lobbied for them before the ICA and initiated a loan fund to see the needy through to harvest. Building on these successes, he tried to institute his long-standing plan of introducing Jewish labor. He did not find Mes’ha to his taste, with its image as a mixed colony where children spoke a brew of Hebrew and mumbo jumbo, with its street that was not Jewish in either form or character, with the fact that its safety was guarded by an outlaw. To him, the import of Jewish labor was the Archimedean screw that could transform Mes’ha into Kefar Tavor. He traveled to Judea, where his infectious enthusiasm motivated others to return with him, marking the start of what was to become the Second Aliyah’s push toward Galilee. All at once, a new spirit infused Mes’ha. Ehrlich made space in his house for a clubroom, and the singing of the hired hands soon dissolved the nighttime terrors and the loneliness that had swaddled the village at dark. Children suddenly had new role models: Jewish guards in abayas and keffiyehs cut dashing figures with their decked-out horses, their ammunition belts, and their weapons. Their imagination fired, Mes’ha’s youth longed to be like Beraleh Schwiger or Yigael the guardsman—a son of Metulla, that is, of Galilee.56

Mes’ha, for one brief moment, was a social and public hub. Here the Second Aliyah founded Ha-Horesh, Galilee’s first workers organization, as well as Ha-Shomer, a body of Jewish guardsmen (which was established on the seventh day of Passover, 1909). Jewish guards and Jewish labor were coming into their own. But the moment passed. Ehrlich became embroiled in a major squabble and was forced to leave the colony.57 With his departure, the bubble burst. A year later the contract with Ha-Shomer for Jewish guards was terminated, the Jewish hired hands were gradually fired, and the harats were restored to Mes’ha’s farmyards.58

Like that of Mes’ha, Reuven Paicovich’s attitude to the Arab milieu was ambivalent. His courage stood out from his first day in the country59 and his memoirs include hair-raising exploits about near-death encounters with highwaymen and miraculous deliverances due to his unfailing heart. He gave at least as good as he got and he tried to teach his sons to fight for life and honor. It was not an abstract message, but something concrete translating immediately into physical engagement. It was the ABCs of Galilee—vital to survival. After the a-Zbekh incident, Paicovich’s neighbors understood that it was best not to tangle with this strong-willed man who itched for a fight, and they chose other fields for their spoil. But if they needed reminding, all they had to do was stray onto his property.

His reputation preceding him, Reuven was welcomed into Bedouin tents to sit and sip coffee with a-Zbekh elders between one scuffle and another. It was a reputation in which al-Insari’s sons too basked, and rightfully so: the boys were hardly fist-shy; as soon as they came of age, they showed themselves eminently capable of thwarting thieves and trespassers.

The frays were governed by ritual and were rarely life threatening. Both Arabs and Jews were careful to stop short of killing lest they stir up blood vengeance, known as gom, and all that it entailed. By an unwritten law of the Galilean wilds, deadly weapons were shunned unless there was absolutely no choice. Paicovich played by the rules of the game.

He observed the rules when it came to Jewish labor as well. National pride was one thing and hiring Jews another. He was already living at Mes’ha during the brief transition to Jewish labor when some fifteen farmers took Jewish workers into their employ. But not he: his name does not appear on any list of farmers using Jewish laborers. He saw no need. Arabs may have been rivals, robbers, constant opponents, but they were part of the landscape; there was no contradiction. Paicovich’s harats were part of his household and when the need arose the harat’s wife nursed his son.

He was not an observant Jew. According to Allon, Reuven was cured of religion after being thrashed by his father for playing with a puppy.60 En route from Odessa to Jaffa, he bickered with ultra-Orthodox passengers who were making the voyage in order to die in the Holy Land. They took exception to his abstinence from prayer; he showed them lofty contempt, undiluted by a scrap of Jewish compassion.61 His wife, Chaya, was highly devout and abided by all of the commandments, minor and major. She kept a kosher home, observed the Sabbath and the holidays with all of their traditional dishes, and lit the candles. It is safe to assume that Reuven did not make the blessing over wine. But he was the center of her universe, and she was careful not to force her ways on him. His feet knew the route to the synagogue but they took him there only on the High Holidays.62 He had a Lithuanian skepticism for anything that did not stand up to proof of reason or perception. The boys all took after him, adding a further distinction to this Mes’ha family. Generally speaking, the fathers’ generation was pious; it was only later that most of the sons turned their backs on religion—not so the Paicovichs. And yet, within a few short years, Paicovich became one of the colony’s leading figures, in all likelihood because of his other virtues.63 In 1912 he became a member of the council, a seat he retained intermittently until the onset of British rule.64

Hard, strict, pedantic, Reuven’s penny pinching was famed: he cut every cigarette in two, smoking half at a time and saving the leftover tobacco in a small box to use later in his pipe.65 Dearth can lead to minginess, and the residents of Mes’ha learned to hoard every sheaf of wheat and every matchstick. But Paicovich never featured among the colony’s poor. His parsimony was ingrained in his life and character. The main thread of his life was the work ethos—man was born to toil. His extreme individualism set the tone in his home. He had no time for small talk, never invited his neighbors home, never visited them for a glass of tea with tzuker, as they called it. Nor did he participate in joint village projects. Proud, reserved, and suspicious, he chose to work on his own with his family and his harat rather than rely on others. To his sons, he strove to pass on his independence, meticulousness, love of work, and courage. Of them, he demanded that they tell the truth, take responsibility for their actions, and lovingly accept punishment for their misdeeds, large or small.66 His integrity was ruthless, he did not know the meaning of mercy, and despite his diligence, conditions at Mes’ha never brought him the measure of ease he had hoped for. Eventually, he was forced to bury his pride and turn to the ICA for assistance.

Their first few years at Mes’ha were good to the Paicoviches. In 1909, their only daughter was born and named Deborah after the biblical prophetess with a connection to Mount Tabor. Eliav (born during Paicovich’s trip to America) and Deborah were still toddlers, but Moshe, Mordekhai, and Zvi already composed an able work force helping their father run the farm. Chaya lent the home its warmth and softness. Kind and gentle in nature and appearance, she sought to round the “sharp corners” in her husband’s personality. As the household’s bookkeeper, she would sometimes secretly manage to return to a farmer requiring seeds before Passover change from the money her husband had charged him. Without advertising the fact, she lent money to the needy of the village. She shielded the boys from their father’s wrath, Reuven’s parenting being based on “spare the rod and spoil the child.” In the cramped conditions of the small house—the dining room was at once the lounge, the kitchen, and the center of family life, while the bedroom served everyone (in summer, the children slept outdoors on mats)—she managed to cook, sew, and keep her home clean and tidy. Possessions were few and soon became worn in a house that had cried out for renovations from day one. Only rarely did she permit herself a luxury, such as visiting her father in Rosh Pinnah. The journey took a whole day and Paicovich was not given to visiting his father-in-law.

The disruptions wrought by the First World War did not bypass Palestine or Mes’ha. Men were conscripted into the army or forced to labor for the war effort. Livestock was requisitioned for military needs. In some sense, Mes’ha’s lot improved: since the country was cut off from the rest of the world and there was famine in the towns, the price of wheat soared. Like all Galilean colonies raising cereals, Mes’ha was spared hunger and even succeeded in selling spare produce. Paicovich and his two older boys, Moshe and Mordekhai, had been called up. Moshe, never having had a yen for fieldwork, had attended the Herzliya High School and excelled in languages; the Turks soon made him an officer. Mordekhai and his father were ordinary soldiers. In 1917, when the Ottoman fate was sealed, Mordekhai and Reuven snuck home, eluding the search for deserters. Yigal was born about a year later. He later laid his birth at the door of his father’s dramatic return from the dread of war.67

Yigal was an afterthought in a rather mature family. By the time he was born, his father was forty-five, his mother about forty-two. His sister, who was closest to him in age, was nine, his oldest brother, twenty-two. One story from Mes’ha about his birth said that his mother feared for his life because he was so small. The midwife consoled her: don’t worry, she said, this little one will yet head the Mes’ha Council!68 After Yigal made a name for himself, becoming the colony’s most illustrious son, the tale became part of the Mes’ha legend.

He was born in heady times of great expectations. Until then, Paicovich had given his children traditional Jewish names. He now outdid himself; he called the boy Yigal—a typical Eretz Israel name redolent of the exultation following the Balfour Declaration and the British conquest. No more dispirited Diaspora names, such as Moshe or Mordekhai or Zvi. “Eliav”—for the child born while the father was in American exile—expressed Jewish resignation to an inauspicious fate: may God be with both the tender newborn and the father. “Deborah,” though prompted by the scenery outside the window, still belonged to the lexicon of common Jewish names. But “Yigal”—the redeemer—suggested new times, a different sort of life experience, high hopes, and a commensurate self-confidence. It was exceptional among Mes’ha’s children. It bespoke great expectations and nationalist goals.

Allon’s memoirs describe the early 1920s at Mes’ha. Presumably, the stories were told and retold so that he absorbed them as a babe on his mother’s lap. One episode that took pride of place in the family saga concerned Mes’ha’s cattle robbery.

One cloud-free Sabbath morning in the early summer of 1920, as most of Mes’ha’s old-timers stood in the synagogue wrapped in prayer shawls, the serenity was shattered by a lad bursting in with the cry that the entire herd had been stolen. The residents of Mes’ha were shocked. Such a thing had never happened before—not even under the Turks. For it to happen now—in the British era—when the troublemakers seemed to have retired and stopped harassing the colony … They quickly pulled themselves together, quit their prayers and the synagogue, and, undeterred by the holy Sabbath, set out in hot pursuit. Paicovich was not at the synagogue, and the news of a robbery on this tranquil morning hit him like a bomb at home. Zvi hastily grabbed for his weapons in order to join the other young men in the chase. Reuven held him back momentarily, for fear of the Gom. But Zvi paid no attention. Paicovich, as the chairman of the council at the time (by his own report), went to see to the colony’s defense against a possible raid by the Bedouin neighbors to the north: the robbery and chase could well whet their appetite for an attack on the disconcerted village. The robbers had come from Transjordan and scurried to get back across the Jordan under cover of Wadi Bira, driving the herd eastward. In their flight, they ran into an ambush laid by Mes’ha’s “posse.” One of the robbers was killed in the dust-up, and others appeared to be hurt. Mes’ha also suffered losses: Moshe Klimantovsky, the son of a widow who managed her farm alone, was slain. Two others were wounded: Nahman Karniel and Zvi Paicovich.

Figure 2. Allon in the arms of the husband of his Arab wet nurse. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Allon family.

With Yigal in his mother’s arms—so the story goes—his mother and father stood outside their home anxiously awaiting news. All at once a rider came into view. It was Zvi; he had left home on his feet only to return atop someone else’s horse. “S’iz gornisht, imi” (“It’s nothing, my mother”), he shouted, his shirt soaked in blood. Chaya fainted. Horse and rider continued on to the pharmacy, but before he could get there, Zvi also fainted. Vigilant neighbors rushed to dismount him and dress his wounds. Mes’ha’s pharmacy served as a clinic and even an infirmary, and Zvi lay there for several weeks before being transferred to a hospital. It was a year before he returned to farm work.

The loss of the handsome, amiable Klimantovsky cast a pall over Mes’ha the next day. The two other casualties hovered between life and death and the air was heavy with the stillness of the grave. It was unexpectedly disturbed by noise on the northern road, not far from Paicovich’s home. He took his rifle and went out to investigate. A horde of merry Bedouin were firing guns and riding toward the village. Thinking them a wild mob come to finish yesterday’s piece of work, he planted his feet on the main road, cocked his rifle, and faced them, a man alone. He warned them not to try to enter the village. Nearly falling over themselves, the Arabs explained that they were on a wedding procession, a fantasiyeh in honor of the bride’s coming to the groom, and no one had the right to block the main road that ran through Mes’ha. Paicovich would have none of it—the village was in mourning, he said, the wounded required quiet, and the bereaved families could not abide the rowdiness; the procession would not pass through Mes’ha! Having said this, he was not a man to back down from what might have been an unnecessary confrontation. Some of the merrymakers soon recognized him and spread the word that it was wiser not to lock horns with al-Insari. The procession turned toward a byroad.69

Reuven’s intrepid stance and Zvi’s injury nourished many a tale, magnified by the fact that a year later, Klimantovsky’s sister married the second Paicovich son, Mordekhai. The episode contained all of the ingredients of the Wild West, including the sense that the authorities could not be relied on to ensure the safety of the settlers.

Its wider context, however, is virtually absent from descriptions by the residents of Mes’ha. In this period, the whole of the Galilee—Lower and Upper—was in turmoil. But the connection to Emir Faisal’s deposition in Damascus by the French escaped Mes’ha’s notice. To the settlers, the raid from Transjordan was a local clash; it was not related to the serious skirmish that had taken place at Tzemah a month before (on 23 May 1920) between the Indian army stationed there and Bedouin attempting to invade from the desert. The people of Mes’ha saw the raid as more of the same, as an extension of the constant battle over grazing land and water sources: a conflict between the lawless and the law-abiding folk. It rankled them that their Arab neighbors—far from coming to their aid—had actually helped the robbers. Nevertheless, the nationalist awakening washing over the colony in those days did not make them view their neighbors as having the same aspirations. The perceptions of Wild Galilee were still paramount.

In the thick tension following the incident, Jewish settlers in the Galilee and the Jordan Valley submitted a strong protest to the military governor in Tiberias for the lapse in peace and security. As a result, the Indian army was stationed at colonies in the Upper and the Lower Galilee, and, after a couple of weeks of uncertainty and fear of war, calm was gradually restored and life reverted to its normal course.70

This unsure interval highlighted Mes’ha’s virtues and faults. The courageous stance on life and property, the unhesitant enlistment of the young in battle, reflected the great distance traveled by former denizens of Lithuanian shtetlach to Eastern Galilee’s untamed frontier. Nearby colonies equally stood up to the test: Yavne’el, for instance, made immediate provisions to supply Mes’ha with a daily shipment of milk (preboiled, of course, so as not to spoil on the way). In contrast, when it was suggested that farming be organized communally, with everyone working together on a different field each day, the residents of Mes’ha could not get their act together: those with nearer fields balked; those with better work animals refused to help neighbors whose beasts were a cut below.71

Paicovich was among the main victims of the robbery, losing five cows and five bulls. Only one other farmer lost more, and only two others matched him72—meaning that his was one of the more prosperous farms in the village.

It was, in many respects, a peak period in Mes’ha’s history and in the Paicovich annals. In the war years, as noted, grain fetched high prices and Mes’ha had plenty of grain. In 1917–18, the rain was generous, producing a bumper crop. Afterward, a constant decline set in, both in harvests and prices.73 Successive drought brought on a plague of field mice that ate away at the meager yields for three consecutive years. Settlers had to borrow money from government sources and the ICA.74 Attempts to diversify cereal farming with dry orchards failed. Only olives and almonds could be grown without irrigation. The vines had succumbed to disease during World War I, almonds were economically unviable, and even olives, so common in Arab villages, did not do well at Mes’ha.

In the Jewish Yishuv in those days, the Third Aliyah immigration wave enlarged the population and injected a boost of initiative, action, and building. Innovation and experimentation were the name of the game, whether in agriculture and industry or in new settlement forms, such as the cooperative moshav, the kvutza or large commune (the forerunner of the kibbutz), or the “labor battalion” (contract workers who lived in collective equality). The times were infused with a burst of youthful energy and the joy of creation. But not at Mes’ha. It seemed to have sunk into slumber, hardly touched by the changes sweeping over the Yishuv. And yet, for a short moment it too seemed to come alive, in the “war of the generations” in the colonies of the Lower Galilee. But victory went to the “old.”75

The triumph of conservatism over renewal found expression in the old farming methods. Mature farmers had little interest in new inventions or mechanization. Uneducated and naturally suspicious, they had no use for the new-fangled notions banging at the doors of their small world. In particular, they were wary of anything that smacked of “bolshevism”; to them, it stood for everything that nipped individual independence and freedom of action.

The question of Jewish labor lay at the heart of the controversy between the “progressives” and the “conservatives.” Everyone agreed that the colony was too small and the Jewish settlers so few as to threaten its existence. Mes’ha’s street retained an essentially Arab character, as in the period of the Second Aliyah. The number of Arabs living there was certainly no less—and sometimes even more—than the number of Jews. The cattle robbery of 1920 gave the Jews of Mes’ha a moment of alarm that their Arab neighbors, including the friends and kinsmen of their harats, would join forces with the thieves. In 1921, thirty-two Jews were reportedly hired as annual workers at Mes’ha, apparently on the same conditions as harats. They soon organized evening Hebrew classes, and outside lecturers included them on their circuit.76 All of a sudden Mes’ha was part of the Yishuv. Yet in less than a year, the number of Jewish workers dropped to nine, after having inspired a local counterculture: a Bnei Binyamin club, an organization of second-generation settlers, was founded in the colony, and most of Mes’ha’s young joined it. Culturally, it did not amount to much. But it accented—and exacerbated—the rivalry between farmers, who considered themselves middle class, and Jewish laborers, who leaned toward the Zionist Left.77

By 1921 it was clear that the dry farming of cereals could not support hired labor, whether Jewish or Arab, and that a radical solution was needed for the colonies’ woes—to reduce the size of the farm units and switch over to intensive farming.78 Of course, no one had the energy to tackle the farmers, the ICA, or the objective conditions. The lack of internal cooperation and the unwillingness of the farmers to establish a representative organization with financial and electoral clout prevented the Galilee’s settlers from constituting the political force that could have improved their lot.

In the eyes of the young Yigal, however, these were the best years. With the exception of his eldest brother, Moshe, who, after his release from British wartime imprisonment, left Mes’ha to work on the Haifa railway, the whole family was together. His mother, Chaya, showered the fair child of her “old age” with love and pampering, while Reuven, too, was not immune to his charms. On one heart-stopping occasion, Reuven, driving a mule-wagon laden with goods, spied Yigal alone in the fields. Unable to rein in the animals because of the weight of their load, he cried out from afar for the child to move out of the way, but to no avail. Yigal slid beneath the wheels. Only after he saw that the child had suffered minor cuts was Reuven able to breathe again. But the incident was apparently traumatic enough for him to recall it fifty years later.79 Yigal’s version of the same incident was different: Reuven, he said, commanded the doctor to save the child or he would have his head.80

Those happy years were dominated by the mother’s quiet presence. The adult Allon described his parents’ home—with its scents and dishes, with the serenity of a Sabbath eve descending on it, as the hub that it was for the colony’s guards and guests—as a short season of motherly grace. It was soon taken from him: after finishing her housework one Friday, Chaya sat down to rest, keeled over, and lost consciousness. The doctors summoned to her bedside did not hold out any hope, while neighbors rallied round to succor an abruptly motherless family. She was gone within the week. The young child could not but feel the change, although nothing prepared him for his last encounter with his mother: “Suddenly, my father came, picked me up in his arms, and carried me to the room where she lay. … I didn’t understand what was happening, but the silence of the family poised around her bed said it all. My father lowered me toward her and I kissed her forehead. If my memory does not betray me, she even turned her eyes on me, which suddenly lit up with the supreme effort of an impossible smile.”81 She was around forty-nine.

The loss was tremendous. Paicovich, only in his early fifties, refused to remarry, whether out of loyalty to her memory or the difficulty of adapting to someone new. The house began to empty out. Even before Chaya’s death, Mordekhai had joined the Bnei Binyamin organization of farmers’ sons to found the colony of Binyaminah. Deborah, fourteen, dropped out of school to assume responsibility for the home and to raise Yigal. Paicovich was never a social animal. After his wife’s death, there were no more visitors to the home and his public prestige waned. Gloom increasingly nestled between the four walls.

Allon wrote of his father as the dominant figure in his and the family’s life. He sketched a man strong and brave, honest and unimpeachable, a proud man standing up to ICA officials, unafraid to take on the authorities or to fight against wrong. In Allon’s hands, Reuven was either the Gary Cooper of the Galilee or a member of the enlightened landed gentry. Contemporaries, however, painted a far different portrait, as did Paicovich’s own memoirs. No one doubted his courage, toughness, or pride. But broad-mindedness or spunk against the “wicked” PICA? Yigal seems to have resorted to wishful thinking. (In the early 1920s, the ICA became the PICA—the Palestine Jewish Colonization Association.)

The relations between Mes’ha and the PICA shed light on the character of the colony and its settlers. Mes’ha was founded with the intention that the farmers would stand on their own two feet after receiving an initial loan from the ICA. Reality, however, got in the way. The farmers were not shy about asking for additional assistance, while the officials, by nature, risked being snared into providing support and fostering dependency, despite all good intentions to the contrary.

Affairs came to a head in the 1920s. The PICA was hard put to balance the books, whereas the farmers had grown accustomed to requesting handouts for all and sundry. Their applications centered on important issues, such as water supply, as well as on minor items. When it came to public institutions—the school, the synagogue, the ritual bath or the community center—the residents of Mes’ha took it for granted that the PICA was to erect them. And when the harvest failed, they thought it only right that the PICA pay the government the land taxes due on their behalf. The PICA was fed up: the more it helped the farmers, the less they helped themselves.82

Paicovich was no different. He too enjoyed being on the receiving end of the PICA’s loans and benefits. Notwithstanding the image of a proud pauper that he liked to tout, he was neither all that poor nor all that proud.

His sense of the PICA’s wrongdoing went back to the very beginning, when the ICA’s Rosenheck had refused him the choice of a colony. But it only grew worse, and after the earthquake of 1927 and the ensuing argument over home repairs, his bitterness took firm root. As he told it, the PICA fixed the cracks in the houses of the other farmers, but not his; he ascribed it to the organization’s dislike of him, his pride, and his independence. He dashed off at least four letters to the PICA administration asking that his house be repaired or exchanged for another. In one letter, he noted: “Permit me to mention here that I have already been a farmer at Mes’ha for twenty years and I never come to the officials with a demand for help.”83 He was not eager to turn to the PICA, he said, but it was now a matter of necessity. The administration remained unimpressed: “We cannot, to our regret, meet your request since we have no budget for same.—Besides, it is time that the farmer understood that the maintenance [and] repair of his house comes under his care—not ours.”84 Paicovich did not let up. In December 1934 he again pressed the PICA for repairs and again was told that the “repair of the buildings falls on the farmer, not on our company,”85 as indeed the leasehold contract stated. It was a typical response from PICA officials weary of the endless demands made by Mes’ha’s farmers; it was not a sign of discrimination. Paicovich made no repairs. He left the house in splendid dilapidation as eternal evidence of his being wronged by the PICA.

The PICA-Paicovich cup of bitters grew fuller with another affair, that of the Mikveh Israel Agricultural School. Paicovich submitted Yigal’s application in 1931 and the boy passed the entrance exam. But Paicovich had no intention of paying school fees out of his own pocket. He hoped that they would come from the PICA: it provided six scholarships for which all of the children in its colonies could apply. There were thirty applicants; Yigal was not selected. A year later, Mes’ha’s only successful candidate quit the school, Paicovich reapplied, and Yigal redid the exam. This time Paicovich stressed the fact that Yigal was a motherless boy and noted the importance of an agricultural education for the future of both boy and farm. Again, Yigal was not among the six winners.86

Paicovich may have been unable to afford the fees, although that is open to doubt: according to Allon, the farm owned a pricey, pedigree horse. And when the boy desired a mule, money materialized for this as well. But nothing when it came to education. Reuven did not think that it was up to him to pay for his son’s education, especially since there was a chance that the PICA would. The matter of house repairs and the school episode may have had something in common: Paicovich was not prepared to lay out money for what others could obtain from the PICA free of charge.

The PICA’s impatience with Paicovich reflected its annoyance with Mes’ha as a whole. In 1930, the residents of Mes’ha filled out a questionnaire presented to them by John Hope-Simpson, who was exploring the feasibility of colonization following the unfavorable report on Zionist settlement produced by the British Shaw Commission on the Palestinian Disturbances of 1929. Based on the questionnaire, the village had thirty farming families at the time and a total debt of Palestine £7,000. They employed forty harat families and another thirty-five temporary workers. None of the hired hands was Jewish.87 At the time, the PICA leaned toward a rescue plan devised for the colonies by the Yavne’el “progressives”: intensive farming, smaller units to boost productivity, mechanization (a tractor and a combine), the seed cycle, modern amelioration and fertilization, and improving livestock with superior strains. The entire plan meshed with the problem of Jewish labor. Smaller units and mechanization were meant to reduce manpower and give preference to skilled, trained labor. Yavne’el adopted the program with the PICA’s support. Mes’ha rejected it. One of the voluble opponents to modernization was Paicovich. In Mes’ha’s dispute with the management of the Galilee Farmers Federation, Paicovich charged: “You (the federation) and PICA must change your attitude toward us.”88 In other words, the fault lay not with Mes’ha’s methods but with the attitude of official bodies.

The dispute grew sharper in the summer of 1931, with Mes’ha rejecting every suggestion to change its lifestyle and let the harats go. The PICA imposed sanctions. Spurning a request from Mes’ha’s farmers to help them obtain outside work, it explained: “Even if we had funds for employment at Kefar Tavor—we would not use them in view of the farmers’ negative position on every suggestion to improve the situation and upgrade agriculture. They object to the seed cycle and to any change in working methods—things that already exist at most of their sister colonies in Lower Galilee.” The conclusion was: “So long as the farmers do not change their views on these questions—they can expect no help from us.”89

The colony’s Z. Eshbol complained: “Because of Arab labor, Mes’ha has fallen from grace in the eyes of [PICA] officials and the federation.” In the spirit of Paicovich’s earlier demand, he called for understanding and caution in officialdom’s attitude toward Mes’ha.90 But while Mes’ha refused to “reform,” the PICA refused to extend assistance.

In 1932, a sunken well at Yavne’el fortuitously yielded abundant water, changing the prospects of the Lower Galilee farm and carrying everyone along in a wave of optimism. The discovery seemed to justify the methods of the modernists after the fact. Craving water on their land too, the residents of Mes’ha did not bother to consult the PICA and dug a well at their own expense. The PICA deemed the unplanned excavation a waste of money. Still, there was no denying that it was a novel local initiative. What’s more, with the PICA’s help, a group of Mes’ha’s farmers got together to purchase a jointly owned tractor.

Following sterile attempts and sterile investments by the PICA, finally, in 1932, Mes’ha’s homes and farmyards were supplied with running water. An entire saga can be written about the water problem, informed by Mes’ha’s bungling in making its demands and the PICA’s in meeting them; the former suffered from articulation problems, the latter from technical incompetence. The efforts to install a functioning system went back to 1926 and were a resounding failure, which was virtually imitated in 1932. Given the day-to-day hardships endured by the settlers, one can sympathize with their bitterness and suspicion of the PICA, although this hardly excuses their passivity or inability to organize for the common good.91