Читать книгу Yigal Allon, Native Son - Anita Shapira - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 4

The Start of Security Work

In April 1936 a new era opened in the history of Palestine. Concurrent with modern Jewish settlement in the country, the dispute between Jews and Arabs over possession of the land became a life-and-death struggle. The brief chronology of Zionist settlement was interspersed with the eruption of riots that earned the lukewarm designation of “Disturbances.” Until 1936, these could be explained away with a variety of reasons that veiled the root cause: a clash between two peoples over one piece of land. In the wake of the Disturbances of 1936 (as the Jews called them; the Arabs called them the Arab Rebellion), the conflict’s national character could no longer be ignored. As in previous outbursts, this time too events began with rioting in Jaffa and the killing of Jewish passers-by. But the political coloring soon became clear in the establishment of the Arab Higher Committee and a general Arab strike. The strike was aimed at forcing the government of Palestine to change its pro-Zionist policy, especially to halt the large immigration that, since 1932, had doubled the country’s Jewish population. The strike lasted for half a year and, this time, the British did not back down. Ultimately, the rulers of Arab states had to step in to extricate their Palestinian brethren from the situation. They asked the strikers to end the strike and enable His Majesty’s government to dispatch a royal commission to Palestine to investigate the problem thoroughly. The Peel Commission, named for its chairman, had wide-ranging powers and concluded that the Mandate had failed because its working assumption—that the two peoples could coexist—had proved false. It recommended that Palestine be partitioned into two new independent states—one Jewish, one Arab—to satisfy the national aspirations of the two peoples. The Jews accepted the solution amid mixed feelings, unleashing a controversy that was to last for years: supporters favored creating a Jewish state immediately, even if only in part of the country; opponents refused to yield an inch of the land, even if it meant risking the lot. The Arabs rejected the recommendations outright and resumed the rioting, which in 1938 took on the dimensions of a revolt. At the time, the Arabs inhabited the country’s hilly spine and the British, like the Jews, were careful not to stray into areas under their control. Order was not restored until 1939 and then only by the British bearing down with ruthless military force.

The period of the Arab Rebellion, to a large extent, overlapped with the formative years of Allon’s generation. Just as the dream of socialism had blazed in the founding generation and the (1905 or 1917) Russian Revolution had been that generation’s defining, existential, and intellectual experience, the physical contest over the land filled the same role for the generation born and bred in Palestine’s Yishuv. This generation did not dwell on politics, strategy, or long-term thinking. It faced an immediate challenge that required neither explanation nor justification: to defend the life, property, and honor of Jews in Palestine.

The Arab uprising took the Yishuv by surprise and wreaked havoc although, ostensibly, the writing had been on the wall. One indication of growing Arab extremism in the country had been Sheikh Iz a-Din al-Kassam’s terrorist group operating in the Jezreel Valley and Galilee in the early 1930s; it finally fell in a battle termed by Ben-Gurion “the Arabs’ Tel Hai”—a reference to the legendary, heroic stand of Jewish defenders against Arab attackers at the country’s northern tip. In 1935 the Arab press rattled with news of an attempt by Haganah to smuggle in arms. Britain’s Parliament thwarted efforts by High Commissioner Arthur Wauchope to set up a legislative council in Palestine. The Jews grew stronger and the Arab population more frustrated. Added to this were the political tensions in the Middle East due to the Italo-Ethiopian war in the autumn of 1935, which exposed the underbelly of the British lion. And yet, when the eruption came, the Yishuv was not prepared for it—not emotionally or organizationally or militarily.

The Yishuv was informed by the key ethos and concept of upbuilding: the Yishuv as a whole and the Labor movement in particular saw themselves as the builders of the country. The right to the land was won by working it; ultimately the land would belong to those who “redeemed” it from the wastes, who transformed a wilderness into a living home. In the Yishuv’s self-image, its key mission was peace, bringing progress and prosperity to all of the inhabitants. This “defensive ethos” rested on the belief that the land could be acquired by peaceful means. It was closely related to the other two ethoses of upbuilding and making the desert bloom, and all that they entailed.

To go from this dream to the Arab Rebellion was a rude awakening. The Yishuv believed that its life was at stake. It had to learn how to fight, and at once. Hereafter, the emphasis shifted to developing means of resistance, a test and effort that drew the top talents. Emotionally, the changing priorities were more digestible to the generation that had just come of age and was less committed than the founding generation to the ethos of upbuilding. “You may wonder, Father, at the military spirit that has come over me”—wrote Israel Galili to his parent. “Not so. The wish to live, the instinct to do something and the love of freedom are what led me now to view Jewish enlistment in the Haganah as the immediate center of gravity.”1

The first shortcoming exposed by the Arab Rebellion, then, was the Yishuv’s lack of an ethos in support of fighting. The second shortcoming exposed by it concerned organization and management. The importance of the military arm of the national liberation movement—the limited, underground Haganah—and the need to place it at the disposal of the movement’s political echelon, represented by the Jewish Agency (JA) and the Zionist Executive, was late to be recognized and hard to acknowledge. The Arab Rebellion upturned traditional thinking and acting, and yet consensus, though vital, remained elusive.2 Formed in 1920, the Haganah was still not central to national consciousness or priorities. Internally, it was riven by political rivalry. Only in 1939 did the various political parties in the Yishuv finally agree to form a Haganah National Command to oversee the Haganah’s activities. It was composed as a steering committee of civilians, equally representing the Left and the Right, and it lasted until statehood.

The third deficiency was military capability: military leaders had no answer to the challenge posed by the Arab onslaught. Security personnel clung to a military conception of passive resistance; in the event of Arab attack, settlements were to hold the assailants at bay until the British army arrived to disperse them. It was considered an achievement just to prevent the aggressors from entering a Jewish settlement. The Arab Rebellion, characterized by prolonged aggression, confounded the settlements and the security establishment. Daily life and functioning were disrupted by the need for nighttime guard duty and the frequent alarms raised against ambushes. In addition, transportation came under attack. For the first time, the Arabs tactically resorted to obstructing traffic routes. The roads became perilous and vehicles passing through Arab areas did so in organized convoys.

Mostly, the Arabs chose the cloak of night for their operations. As dark descended, dread set in: what would the night bring—shooting at windows, the burning of fields, the chopping down of trees, or an attack on the whole settlement? A single volley of shots was enough to banish sleep from an entire community, rousing everyone to their positions. Guards sped to high lookouts, a spotlight—if there was one—sliced through the darkness, and mothers tried to soothe children while hiding them beneath the beds. The settlement fence served as the defensive border. Beyond it stretched the black of night commandeered by the assailants. From their posts, defenders would see fields being torched and watch their sweat and toil go up in smoke. Common wisdom had it that it was better to incur damage to property rather than to the body. The assumption was that the Disturbances would soon die down. Until then, the Jews were to prepare for self-defense but take no undue risks.

This conception reflected a mixture of ideology and a lack of combat skills. The desire to avoid escalation in the Jewish-Arab national conflict, to refrain from bloodshed, and to have peace were ideological components. Soon, an additional consideration came into play: the Jewish political leadership had had its fill of riots and inquiry commissions that came to investigate the causes and left with conclusions placing aggressors and defenders on an equal footing. The leadership wished to highlight the one-sidedness of the Disturbances—Jews were being attacked without retaliating, and it was incumbent on the government, which was responsible for law and order, to come to their defense. Furthermore, following every wave of unrest, the British tended to make political concessions to the Arabs. By highlighting the guilty party, the leadership hoped to make it tricky for the government to reward the aggressors at the expense of the Zionists. Indeed, despite Arab demands to the contrary, Jewish immigration did continue this time as the government refused to bow to violence. Added to this was another political factor: the prospect of incorporating Jews into the defense network and creating a legal military force under British command. The longer the Disturbances lasted and the more severe they became, the political advantages of this policy of restraint, as it was known—taking no initiative for either assault or counterterrorism—overshadowed its conceptual roots.3

Still, there was the purely prosaic military incapability and lack of an operational response to the new Arab tactics. In Allon’s view, “Initially, the consideration of restraint stemmed simply from the unavailability of a force [able] not to [show] restraint.”4 The truth is that even the “big wide world” did not know how to deal with guerilla warfare at the time. The British army, too, from whom the Jews learned the ins and outs of war, found itself hard put to cope with night raids by small units vanishing back into their villages. Response was slow to develop.

It remains a moot question of who actually imparted the new theory of war to the Yishuv’s young. Opinion is divided over Yitzhak Sadeh and Elijah Cohen (Ben-Hur), on the one hand, and Orde Wingate, on the other. What is certain is that in the years 1937–39 the combat methods of Palestine’s Jews were radically revamped, spelling a veritable revolution.

Heralding the turning point was the appearance in the Jerusalem Hills of the mobile squad, which moved from point to point as needed rather than being stationed at any one spot. The unit was soon issued a vehicle and, in stark contrast to the helplessness and inexperience of frontier settlers, it whisked people with military experience to trouble spots.5 This was the start of what became known as “going beyond the fence”: no longer accepting passive resistance inside a settlement while abandoning fields and orchards, but defending the entire area right up to nearby Arab villages. Arabs were no longer the sole masters of the night and fields; these now became part of the Jewish arsenal as well. To this end, small units were created to be able to move quickly and quietly. The ammunition also changed since only short-range weapons could be used at night, employing brief but concentrated firepower. The submachine gun made its debut alongside the grenade, the preferred weapon of nocturnal combatants. Capping these developments was the art of the ambush, which utilized the night and fields to strike and fire at entrapped armed bands.

Yitzhak Sadeh, one of the fathers of the mobile squad, claimed that he had acquired his knowledge of sorties in the Russian army, both in a reconnaissance unit during the First World War and, more so, in the Red Army during the Civil War.6 Those training schools had taught him a number of basic principles—unconventional frameworks, improvisation, mobility, and optimization of manpower and weapons.7 The solution that took shape was elegant in its simplicity and, in retrospect, seems almost self-evident. Sadeh’s greatness was that he arrived at it from within, in collaboration with colleagues and followers. He grasped the nature of the revolution and was able to infuse in those around him a sense of the importance of things.8 It was a theory of war supported by a young base, the generation then coming of age. On his dry runs with the mobile squad in the Jerusalem Hills, Sadeh found the young ready to try out his new methods, unflinching and itching for action.

Allon’s case was typical of the way that Sadeh recruited his “soldiers”: Allon began his formal career in security work in the summer of 1936. That August, he was inducted into the Jewish Settlement Police (JSP),9 an auxiliary force formed by the British to help furnish defense for Jewish settlements throughout the country. It was the common track for young Jews: here, draftees were trained in the use of arms and kept on the alert to come to the aid of beleaguered settlements, escort convoys, or provide cover for farmers working in the fields. The JSP served two masters: one, British and official; the other, the Haganah and underground. This hardly made their lives any easier. On the contrary, often it resulted in entanglements that demanded all of the diplomatic skills of Yehoshua Gordon, their commander and the liaison between the two chains of command.10 In any case, many of rural Palestine’s young men, including Allon, received their initial training in the JSP’s paramilitary framework.

Yigal’s military activity was more or less a natural outgrowth of his childhood involvement in the ritualistic squabbles between the residents of Mes’ha, notably his father, and the a-Zbekh Arabs. For him, as for other residents of Mes’ha, the notion of holing up within Mes’ha’s walls while Arabs destroyed fields and orchards was foreign and unreasonable. Mes’ha’s villagers had always “gone beyond the fence” without any explicit policy. Allon carried with him the memories of the 1929 Disturbances, when his father went out to guard and left him, an eleven-year-old boy, all alone. He would scramble up to the attic, remove the ladder to keep the rampagers away, and wait with an axe in hand, a provision Reuven had made for his self-defense. The mere thought of having to use the “weapon” had made him queasy and given him nightmares.11 But that had been years ago. The sense of helplessness of that experience was now replaced by robust action.

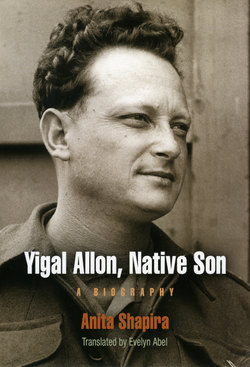

Figure 8. Allon as a sergeant of the Jewish Settlement Police, 1937.

Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Haganah Archives, Tel Aviv.

Allon, early in his career in the JSP, caught the eye of Nahum Kramer (Shadmi), the commander of the Tiberias bloc of the Haganah. In no time at all, Allon was appointed the commanding officer of the tender, an eight-man van outfitted with rifles, guns, and usually a Louis machine gun, along with—contrary to British orders—“illegal” grenades. In theory, the vans were financed by bloc settlers for their defense and placed at the disposal of the bloc’s settlement police. In practice, the vehicles were purchased by the JA executive. The British had no objection to the JSP improving its mobility; they themselves would sometimes use the vehicles and manpower during the Arab Rebellion. But the pretense was kept up that the vehicles were a local initiative for settler needs in order to ward off possible accusations about the JSP’s dual command. The vans were considered the height of operational advancement at the time, and their effects were certainly felt in the field. They were soon converted into armored cars impregnable to the light firearms used by Arab rebels. Every bloc had its own van and commanding officer, who was appointed by the bloc commander.

Allon already had the reputation of a shrewd, daring young man in the JSP when he met Yitzhak Sadeh. His description of the encounter approached the biblical: in the summer of 1937, as he was turning a threshing sledge—monotonous work ordinarily done by Arab laborers who, however, were staying away because of the Rebellion—a boy ran up and summoned him to his father’s house. The boy was the son of Mes’ha’s Haganah commander, and Allon, he said, was wanted because of the arrival of a high-ranking Haganah officer. Allon’s first impression of Sadeh was disappointment: he was tall, portly, balding, and spectacled, and he had an oleaginous growth on his forehead; he looked sloppy in shorts, drooping knee socks, and frayed sandals, and, if this were not enough, he was missing several teeth. Not thus had Allon imagined the military hero.12

The Haganah had just decided to set up a new subdivision of field companies and Sadeh was recruiting promising candidates. He had managed to persuade the Haganah’s senior cadre that the field companies should operate under their own command, drawing manpower from all over the country.13 He was looking for recruits with a track record and he inducted members of the mobile squads and young men who had made a name for themselves in the JSP. This is how he came to Allon.

He suggested to Allon that he join the new national contingent and bring along his friends from Mes’ha. Yigal may have found Sadeh off-putting, but he agreed at once: he had been selected for an elite unit and any other response was inconceivable. Under Sadeh’s instructions, he mustered his peers at dusk for a night exercise and the group set out through the dark fields. Sadeh, in front, hardly set a good example: his foot managed to find every stone, every twig, shattering the silence. And yet, the solid figure striding at the head of the column radiated confidence. The purpose of the exercise was to lay an ambush near the Maghrebi village some four kilometers from Mes’ha. The ambush was laid, the flanks secured and prayers offered for the sighting of an armed gang. The prayers went unanswered. Sadeh ordered “his troops” to fire several volleys in the air toward the village and return to Mes’ha. In Allon’s yard, he sat them down around a small campfire to sum up: the goal, he said, was to harass the Arabs so as to end their mastery of the night. Surprise attacks in Arab areas would force them to assign manpower for village defense, hampering their offensive capability in Jewish areas. There was to be no personal terror against Arabs—he stressed—but attack was to be answered by attack, forcing the Arabs onto the defensive.14

For Allon and his friends it was an epiphany: “Fragmented thoughts that had long flashed through our minds suddenly came together in a full-blown doctrine. We were all impelled by a terrific feeling and we knew instinctively: he’s the man.”15 Though this description may have been colored by subsequent encounters between the two men, there is no denying the strong impression Sadeh made on the boys champing at the bit. Here was an adult who spoke little and did a lot; who not only did not shrink from danger but was eager for battle; who proposed simple, obvious, bold, and effective operational strategies. And above all, he had the charisma to imbue confidence in his followers and shower them with love. The romance between Sadeh and the Yishuv’s young began with the field companies and spawned a new generation of active warriors.

In the months following, Allon was busy dismantling his father’s farm and moving to Ginossar. He continued his duties in the Tiberias bloc of the JSP under Nahum Kramer and was soon called up by the field companies for a five-day officers’ training course at Kibbutz Ayelet Ha-Shahar.16 It was the Haganah’s first practical course in field weapons and fieldcraft. The focus was on battle drill. It included target practice with guns, and grenades, the use of machine guns, and an introduction to sabotage. Hours were spent on fieldcraft and night walking.17 The cadets learned to devise a plan of action, allot and organize manpower and equipment, read maps, set up inter-unit communication, reconnoiter, and, above all, to lead men in battle.18

The course was aimed at producing squad commanders to train bloc personnel. At Ginossar, for example, Allon then gave a course on the friction grenade, which to detonate properly required a few seconds’ delay between releasing the safety pin and hurling the grenade. Allon would stand next to the learner and have the latter count to ten before letting it fly, while the rest of the pupils took cover behind mounds of earth—just in case. In one of the drills, an apprentice left out the counting. He released the pin and made ready to throw the grenade. Everyone tensed. Allon clamped the man’s arm and prevented the motion. The pupil struggled to get free. Allon coolly continued the count to ten and only then did he allow his charge to continue. None of those present ever forgot the incident.19