Читать книгу Yigal Allon, Native Son - Anita Shapira - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 3

Ginossar

Allon’s posthumous papers contained a draft for the opening of an autobiography beginning with his move to Ginossar: “The heavy truck pulled up at a … junction, one of the roads leading to the settlement of Migdal. The genial driver from Kibbutz Kefar Giladi parted from me with a warmth underlined by wishes for full integration into the kibbutz. … I hefted my heavy knapsack onto my back and crossed the road on foot towards the young kibbutz. I crossed the Rubicon, and did not look back.”1

Yigal’s crossing of the Rubicon meant forsaking his father’s world for that of his young friends. The generation gap deepens in times of revolution and rapid change. Even if parents belonged to Eretz Israel’s founding generation of brave, hardy revolutionaries, so great were the differences between them and their children that communication became forced and superficial. Things were worse still in the case of most of the parents, who had only recently disembarked on Jaffa’s shores. Their understanding of what was going on in the country was limited, their lives passing in a kind of partial fog of bewilderment and incomprehension.

It is little wonder, then, that the youth bred in Jewish Palestine regarded themselves as a tribe apart from their parents and adults in general. Their primary frame of reference was the peer group. It, in every sphere, determined the behavioral norms, from articles of fashion to styles of speech, from the approach toward school to the attitude toward parents. The power it exerted on its members—virtually tyrannical—was seen as an expression of their release from adult authority, of an exodus from bondage to freedom. The peer group, or hevreh as it was called, was a company of willing partners to a particular path, a specific lifestyle.

“Good” hevreh went to live on a kibbutz. Going to a kibbutz entailed identifying with a youth group. Such was the force of the perceived generational differentiation that it lent the sense of togetherness an emotional bond reserved in other societies for tribe or family: here, the hevreh were the tribe. Those who didn’t “belong” felt like outsiders, out of place, ostracized.

The fact that Yigal went to a kibbutz was above all a mark of belonging to the hevreh. Graduates of the Kadoorie school had no doubt that joining a kibbutz was the right thing to do. Choosing Ginossar was accidental. Kadoorie had a visit from Yehoshua Rabinowitz (Baharav), a member of the Ha-Noar Ha-Oved (HNHO) kevutzah (group)2 at Migdal. He spoke to the graduates about the hardships of life at Migdal in the Ginossar Valley, about the attempts to settle on the PICA lands along the Sea of Galilee at the mouth of Wadi Amud—an area that teemed with lawless gangs and where no Jewish plowman had ever set foot. He painted a picture fraught with tension and hazard: shortly before his visit, armed bands had fallen upon members working in Migdal’s orchards and wounded one of them. Knowing his audience, he overstated the perils: night after night, there were gunshots, he said. Their imagination lit, Kadoorie’s hevreh decided to go to Migdal.3

A young kevutzah, subsequently known as Kevutzat Ha-Noar Ha-Oved Migdal, had arrived at the colony of Migdal in 1934 to work and wait for a leasehold to a collective settlement of its own. The nucleus consisted of graduates of Tel Aviv’s school for workers’ children who had gone on to study agriculture at the Ben Shemen Youth Village.4 Most of them had trained on hakhshara farms of Hever Ha-Kevutzot and preferred to keep a neutral profile in terms of affiliation with a kibbutz movement. In 1935, they were joined by a group from Kibbutz Ein Harod that sought a connection with the Histadrut’s HNHO youth organization as a preliminary to tying up with the Kibbutz Me’uhad (KM) movement. For years, the veteran core at Migdal, associated with Hever Ha-Kevutzot, held sway: they too identified with HNHO, but they carefully guarded their independence of any kibbutz movement or stream.5

In the Plain of Ginossar, the PICA owned some five thousand dunams (1,125 acres; 500 ha) of land. Part of this was tilled by Arab villagers from Abu-Shusha, next to Migdal, and part was tilled directly by the PICA under its own manager with the help of Arab laborers. At the eruption of the Disturbances, the PICA realized that the solitary Jewish manager was in danger. It now agreed to a proposal from Abraham Hartzfeld of the Histadrut’s Agricultural Center to lease lands to Kevutzat HNHO, Migdal, and the group was hired to turn over the soil and uproot the wild blackthorn north of the plowed area. During the work there was tension in the air. On one occasion, the guard was late in spotting a gang attacking from Wadi Amud, and one of the plowers was wounded.6

When Yigal arrived in July 1937, several months after his friends from Kadoorie, the course of the kevutzah had already been decided: in February 1937 Kevutzat HNHO, Migdal signed a contract with the PICA; the kevutzah was to buy the hay the PICA had sown at Ju’ar (Ginossar’s Arabic name) for Palestine £250 and harvest it.7 The entire plain north of Migdal had not a single Jewish settlement and served as a transit route for bands from Syria and Transjordan. This lawlessness aroused the kevutzah’s slim hope that it would be permitted to settle on these lands. The reason it gave was that it would guard the hay from arsonists; the goal, however, was to set down stakes in the plain, in the hope that the PICA would subsequently find it hard to dislodge the group. Abraham Hartzfeld was party to the calculations and encouraged the ketvutzah.

On the eve of Purim, March 1937, a convoy set out from Migdal to the cultivated area and, within days, the members of the ketvutzah had raised a tower-and-stockade settlement—one of the hallmarks of that frenzied period: some ten dunams of land were fenced off, and within this area a watchtower was thrown up, a gravel-filled fence was built, and one hut, then another, were knocked together, along with a few tents. The small camp, it was explained to the PICA official, was necessary to protect the site.8 The PICA’s Palestine director, who was based in Haifa, forthwith notified the members of the kevutzah that as soon as they had gathered the produce they were to dismantle the guard post and hut and get off the land.9 The kevutzah—now called Kevutzat Ginossar for the first time—made no promise.10 Meanwhile, Hartzfeld stepped up his pressure on the PICA to settle these young pioneers who had shown such dedication and readiness to defend the land in those hard times, for this was the most effective way to ensure Jewish ownership over the land and make good use of the water-rich fertile soil in the area.11

By the time Allon arrived, it was no secret that the PICA did not share Hartzfeld’s viewpoint. He treated the PICA’s holdings as national land; it regarded the Ginossar camp as trespassing. Yet the young men and women clearly had no intention of leaving, continuing to hope for some sort of accommodation. The PICA wasn’t interested: it wanted the kevutzah off its land. The Agricultural Center tried to placate the PICA, taking care not to dent its prestige or mar relations with the Rothschilds, the company’s owners. Ginossar’s members were also prepared to placate the PICA—as far as lip service went.

The PICA had the law on its side, along with the financial power of a large settlement company and the force of political pressure: so long as the conflict with Ginossar remained unresolved, the national institutions, including the Jewish Agency (JA) and the Agricultural Center, could not assist the young settlement. The budgetary stranglehold caused Ginossar severe hardship in the early years and was a direct result of the PICA’s pressure. Nevertheless, the PICA’s public position was also the source of its weakness: it was no ordinary private company; rather, it was driven by Zionism and was not immune to the influence of settlement bodies and Jewish public opinion. There was thus little chance that it would use force to evict this kevutzah of fine young people, even if they were squatters. Nor was it reasonable that it would appeal to the law since turning to the British could provoke an outcry.12 The Ginossarites bet on the PICA’s feeble reaction, and relations settled into a regular pattern: an attempt was made to negotiate; the kevutzah acknowledged its wrongs and promised to behave better in the future if the PICA forgave it its sins and recognized the status quo; the PICA refused to relinquish its holdings, demanding the kevutzah’s removal; and negotiations collapsed. But every such failure led to further encroachment by the kevutzah, to another fact on the ground in blatant, audacious defiance and total disregard of the PICA’s objections.

The determination of the young to stay at Ginossar no matter what was echoed in their battle cry of “Ginossar and only Ginossar.” Apart from the site’s beauty, which chained them with love, its farming potential was enormous. “Better that we sit here waiting for this land for a year, two, three, five, for even then we will draw more from this soil than from any other,” said Israel Levy, then Ginossar’s central figure.13 As time passed, the bond to the land only tightened. Time was in their favor, for each passing day there meant another patch tilled, another pipe laid, one more birth, one more burial.

When Allon came on the scene, the pattern of the dispute over Ginossar’s illegal camp was already set, and he took an extreme position on the matter of placating the PICA. When it became clear that the clash would squeeze the group financially, Allon made a statement at one of the assemblies that became Ginossar’s catchphrase: “We will sow two hundred dunams of wheat and ten dunams of onions and we’ll eat bread and onion.”14 This bravado—undoubtedly nourished too by his great love for the bulb that showed up in his every salad—summed up Ginossar’s resolve.

Allon seems to have been eager for the confrontation with the PICA. He could not have been oblivious to the difference in Ginossar-PICA relations and those between Mes’ha’s old-timers—his father included—and the PICA. Mes’ha’s farmers had faced the PICA cap in hand. In contrast, Ginossar’s young were the active element, pushing the PICA into a resigned, passive corner. The role reversal between initiator and submitter, between the party in control and the party forced to knuckle under, must have put a song in his heart.

A few months later, at the height of the Arab Rebellion in August 1938, Ginossar’s land-grab aims took another step forward: one weekend, as the PICA official in charge indulged in his Sabbath rest, the kevutzah mobilized to install a small pumping station, pipes, and an irrigation line from the Sea of Galilee to a 20-dunam tract; the group also planted a vegetable garden. The PICA issued a strenuous protest: the group was to remove the pipes and uproot the tomato plants.15 Two weeks later the PICA received an inordinately courteous letter requesting its permission to create a winter vegetable garden at Ginossar—an idea “that can shore up our stamina in these troubled times and further bolster our readiness to preserve the integrity of the PICA’s lands at Ju’ar as we have done to date.”16 The letter ended with the disingenuous hope that when the PICA decided to settle these lands, it would look on the Ginossar kevutzah as a suitable candidate. In vain did the PICA protest and threaten legal action.17 The kevutzah blithely went about its business, affably ignoring the company.

In the autumn of 1938 the Arab Rebellion peaked and the local security situation badly deteriorated. In one incident, an Arab gang fell upon a Jewish neighborhood in Tiberias and, meeting no opposition, killed, wounded, and plundered (see the next chapter). As far as security personnel were concerned, this only made the small settlement point on the Kinneret shore all the more important. Meir Rotberg, of the Haganah High Command, applied to the PICA not only to leave Ginossar in place but to enlarge it (11 October 1938).18 He was seconded by the Haganah’s district commander, Nahum Kramer (Shadmi), who wrote to the PICA to expand the settlement point and fortify it properly.19 Hartzfeld too suggested that the PICA broaden the settlement for security reasons, undertaking to have the kevutzah removed should conditions change. The PICA mulled over the matter with long letters going back and forth between the Haifa executive and the Paris head office. Hartzfeld’s innocent proposal aside, the PICA’s people knew very well that if they officially recognized the kevutzah on the land, this would mark the start of their concession to settlement there. The PICA wavered.

Ginossar’s members did not. On 4 November 1938, some weeks after negotiations started about extending the site, they began to move the entire outfit from Migdal down to Ginossar. For about a year and a half, part of the kevutzah had lived in two huts at the lower camp, working and guarding the lands on the plain, while mothers, children, pregnant women, and some of the men continued to live in the old camp at Migdal. Communication between the two parts was problematic if not downright dangerous, and the separation was not healthy for internal cohesion. Beyond the very real security and social worries, however, the kevutzah wished to exploit the situation to establish its home at Ginossar. “We have come out well with the PICA”—Sini wrote his parents on an optimistic note—“it seems that after the Tiberias incident they are more inclined to give in to every demand made in the name of security, and there is hope that we will succeed in going down to Ginossar this week in peace. It also looks as though the money question will be resolved with ease and we will settle on our land.”20 But the PICA, it transpired, did not swallow the bait and Ginossar’s members were furious. The PICA dilly-dallied in its response to the Haganah, which was seen as a snub to security personnel, inconceivable insolence, and a quasi-license for independent action.21

The move down to Ginossar was organized as a military operation to the very last detail: it was scheduled for a weekend when the PICA officials in Tiberias could be expected to relax their supervision over the intrepid squatters. The huts were moved in toto by rolling them along pipes. Construction material had been prepared in advance to fortify the enlarged settlement point and secure the dining hall and children’s quarters. Everything was well planned—and then the heavens intervened. Contrary to all forecasts for clement weather and moonlit nights for that Friday in early November, it started to pour without letup. The members got soaked to the bone, the truck got stuck in the mud and had to be extricated by a tractor, and the entire schedule was thrown off kilter. Mustering the heroic effort that became part of the Ginossar saga, the members managed to knock together two extra huts for shelter from the rain, but all hope of completing the move in two days was lost.22

The PICA, of course, was incensed: the impudence of these young people had exceeded all bounds. The Haganah High Command announced that it had no hand in the affair; it had not given the kevutzah permission to do what it had done. Hartzfeld and the Agricultural Center also fumed: they too had not been consulted and had certainly not given their consent. But once the dust settled—or the mud dried—the question again arose of what was to be done about this endearing company of squatters. Ultimately, the PICA limited its reaction to denying members of the kevutzah employment in its local public works. This strapped the group financially but did not endanger its existence.23

“Now, our main difficulty is our relations with the national institutions [namely, the JA and other central Jewish bodies]. The PICA is ostracizing us, Hartzfeld threw our delegate out of his office, Kofer Ha-Yishuv [a body that supported endangered settlements] canceled its promised assistance under pressure from the PICA, and every month we have about P£100 of bonds to pay”24—Sini described the repercussions of having seized the land. The Agricultural Center was truly annoyed. Yet, when the PICA withheld payment owed to the kevutzah for work done, Hartzfeld remonstrated. “It is unthinkable that the PICA executive employs such measures”, he declared.25

The move to Ginossar launched a new chapter in the kevutzah’s life. Financially, the group still relied chiefly on outside jobs, though members tilled a vegetable patch, which was a kind of auxiliary farm, and began to raise animals, building a chicken coop, a cowshed, a sheep pen. They also tried their hands at fishing in the Sea of Galilee. One of the quickest branches to develop was the children’s house, lending members a sense of permanence, of home.

Life at Ginossar’s small farmyard was far from easy. Every three months, Dr. P. Lander of the Histadrut’s Health Fund made the rounds with an eye to preventive medicine. After the doctor inspected hygienic conditions and living quarters, he stated in his report for April 1939 that “the camp is in a terrible anti-sanitary state.” The kitchen, dining room, and their surroundings were full of flies and garbage rolling about nearby. The shower was not yet finished and there was a lot of rubbish near it as well, and as to the toilets—the less said the better. He ended the report thus: “This sort of camp state could be a source of all types of infectious diseases and malaria.”26 The next report, in July 1939, reported a sharp improvement in hygiene, especially in the delicate respects mentioned above.

Yet the basic problem of overcrowding remained. Ginossar had sixty men and forty women at the time, including twenty-two families with twelve small children. All of these people lived in two huts of seven tiny rooms, three tents, and five lean-tos. Families did not have their own rooms or tents, and couples often had to share with a redundant “third”—the notorious “Primus” from the early 1930s when growing aliyah swelled the kibbutzim.

Collective welfare, as a rule, took precedence over individual life. A member had to be prepared to submit to group judgment in all affairs. One member wished to attend his sister’s wedding. Since this entailed a loss of work days, the question was brought before the general assembly; because it did not sanction the trip, the member left the kibbutz.27 The members agreed that every family was to have only one child at first. When a young mother fell pregnant for a second time, the general assembly discussed the option of abortion (which was voted down).28 It did not occur to anyone to protest the public discussion of intimate affairs. In the case of a couple that separated, the woman demanded that the kevutzah oust her ex-partner;29 the question discussed by the assembly was whether her pressure should force the man out. Nobody objected to the group’s right to decide matters of personal status if they affected the character or vitality of the small society. The ambition of members to pursue a specific occupation or further studies was considered a luxury no young kibbutz could afford.30 One of the typical reasons for asking for leave was “parental assistance,” that is, the need to help aging parents who had no financial support apart from a child on a kibbutz. To counter the problem of absence, such members were asked to persuade their parents to come live at the kibbutz.31 Considering the conditions at Ginossar—overcrowding, no minimal sanitary standards, polluted drinking water, endemic fevers32—it was an impossible demand. The person who made it was Allon: “True, parents would have to make an acknowledged effort to adapt to the kevutzah”—he said—“but if their situation is so hard, they can come to the kevutzah and find in it a solution for themselves and for the kevutzah on this question.”33

Dearth was rife. Legumes were the staple diet: bean soup and more bean soup. Meat hardly ever featured on the dining hall table. The food was flat, prepared by a young woman never initiated in the art of cooking by her mother. But given the ordeal of cooking in the heat of the Jordan Valley and in Ginossar’s primitive kitchen, the poor girl who slaved away could hardly be blamed.34 Ginossar’s newsletter from the end of October 1938 tells of a decision by the kibbutz assembly to send a member to help and encourage a sister kevutzah that had just settled at Hulata (to the north). This formal resolution was never put into practice because the warehouse could not supply the slated member with a pair of shoes.35 Only in March 1940 did a radio arrive at Ginossar, and it, a big, shiny Philips, then common in kibbutzim, was allotted a place of honor in the dining hall. The Ginossar newsletter reported the event: “It must have a fixed, permanent place, on some cupboard or special crate in the corner of the dining hall, rather than continue to stand on the piano; this is inconvenient and, what’s more, not good for the piano. It would also be a good idea to make some sort of cover for the radio, of cloth or wood, otherwise the flies in the dining hall—which are not few—will change its shiny color to speckle-bound.”36

In these conditions, some strong cohesive force is needed to counter a temptation to leave. This role was filled by the PICA. Ginossar’s collective character was consolidated in its wrangling with the PICA. The slogan “Ginossar and only Ginossar” evolved into lyrics for songs in hora circle dances, the speech of skits, and the battle cry of those hard times, protesting against the whole adult world. Constant tension and uncertainty about the future lent collective life the spice of danger that molds solidarity. Everyone felt responsible for the farm’s survival. Anyone leaving Ginossar quit not only the kibbutz but also the battle, abandoning comrades to struggle along on their own. This had nothing to do with socialism but with the sense of siege felt by an endangered group. In many frontier communities, the security situation filled the role of social linchpin. At Ginossar, the PICA played a similar role.37

Allon’s reputation preceded him to Ginossar. His friends from Kadoorie had sung his praises, and the kevutzah knew to expect a brave young hero, a born farmer who did not flinch from clashes with Arabs. Upon entering the yard at Migdal, he was immediately assigned to the small camp at the bottom of the plain, where the more daring members tilled the PICA’s lands. And that first night, he was posted to the middle shift to guard from 12 to 2 A.M.38 Allon did not manage to reach any great heights at Ginossar, for within months, Nahum Kramer (Shadmi) appropriated him for a sergeants’ training course given by the Haganah. Allon left.

Nevertheless, his heart was already lost to Ginossar. In 1936 the kevutzah was enlarged by a group of German-Jewish youth educated at Tel Yosef. They had been on a kibbutz for two years now and found it all overwhelming: the Hebrew language, the collective life, the hard work. The period was rough: it was the start of the Arab Rebellion and the tenderfoots were called on for guard duty on top of their daily work load.39 Ginossar’s members began to grumble that the “match” with the group from Tel Yosef had been a mistake. Nor was the crowd from Kadoorie sympathetic to the heartbreak of the German girls who were asked to deposit in the common warehouse all of the fine clothing they had brought with them—their mementos from a faraway home. Some, however, were charmed by the foreign girls who were so different from those they were accustomed to. Sini and his friends told Allon that they were reserving the prettiest one—Ruth Episdorf—for him.40

Ruth Episdorf had immigrated to Palestine from Germany in 1934. Her family stemmed from Poland, although her father had served in the German army and the family had taken pains to integrate into German society. Her father was a sales agent, her mother a housewife. Hitler’s rise to power was traumatic. At fifteen, Ruth, was expelled from school, putting an end to her formal studies. Her father died of a heart attack, and as the family sat shiva in mourning for him German soldiers burst in on them in search of him. The shock was too much. The family’s vague Zionism gelled into practical action. Ruth joined the Habonim youth movement, which emphasized returning to the land of Israel and settling on a kibbutz. This became the ideal that illuminated the darkness of those days in her native country. The three Episdorf sisters immigrated to Palestine; Ruth arrived with the training group at Tel Yosef. Her mother deferred her own emigration, not wishing to be a burden on her daughters. Ultimately, she delayed too long and met her death in the Lodz Ghetto.

Ruth’s sights were set on working in the cowshed. But city girl that she was, she did not take easily to physical toil and so did not meet the challenge at Tel Yosef. At Ginossar, she again tried her hand in the cowshed. Later, she was proud to be assigned to fieldwork. In the early years, she fell prey to various illnesses, including typhus and malaria. There were emotional difficulties too: she lacked the mentality and social traditions of Yishuv society, which was predominantly “Russian”; and moreover, there was the shame of hailing from the country of the Nazis. She felt inferior to the young native Jews around her—and they certainly did not go out of their way to make things any easier. She eagerly adopted the pinafore, the embroidered blouse, and the elastic-bottomed shorts, an outfit that was almost a status symbol of the new society. The desire to “assimilate” was strong, and even if there was little sensitivity to or understanding of the woes of an individual, a foreigner, an orphan, there was something spellbinding about Ginossar’s young society: it had the air of a band of boys and girls on a desert island; a whole world that consisted only of themselves.41

All of the girls at Ginossar were attracted to Yigal: apart from his reputation as a farmer and warrior, he was handsome, nice, cheerful, and good-hearted.42 It was only natural that his choice would be Ruth, the “star” of the German group, as his friends said.43 He was everything an immigrant girl could wish for: his manly qualities aside, he was native born, a sabra personified, and well-ensconced in the society to which she aspired to belong. Their very different cultural backgrounds added mystery and charm to the relationship. But they had also undergone a similar experience—a severance of roots: Allon from Mes’ha and its world; Ruth from the land of her birth and parental home. For both, Ginossar held out the promise of a new start, hope for a future not lodged in the past.44

A mere few months separated Allon’s break with Ada Zemach and his attachment to Ruth. Was this an indication that he had been hurt by Ada’s refusal to join him on the kibbutz? Whatever the case, his relationship with Ruth was on an entirely different footing: With Ada, he had been older and more experienced in affairs of the heart, even as he was her inferior socially and culturally. With Ruth, he was the dominant partner from the start, having the social and cultural edge as well. Neither was broadly educated and, in this sense, they were equal. But he, of course, had the added advantage of a native over an immigrant.

They must have been the best-looking couple at Ginossar if not in the whole Jordan Valley. They soon moved into a family room, which meant half of a room in a hut along with another family and the infamous “third.” Formal marriage, according to the laws of Moses and Israel, took place later, apparently around 1939, in a mundane atmosphere stripped of the romance surrounding their move to the family room. One day, after work, Allon and Ruth simply drove to a rabbi in Tiberias accompanied by two members of Ginossar who served as witnesses. The rabbi lent them a ring for the ceremony and that was that.45 There were no relatives present, not his father or brothers, not her sisters.

Ruth soon understood that Allon would be away a lot, yet it never even entered her head to complain. Security came first and everyone was enlisted, in spirit if not in fact. Security work epitomized the apex of commitment and lent an aura to both the volunteers who performed and those who were close to them. Allon was well liked by the members of the kevutzah even though in the difficult years of 1938–40, he spent little time at Ginossar.46 And then something happened that suddenly brought him home.

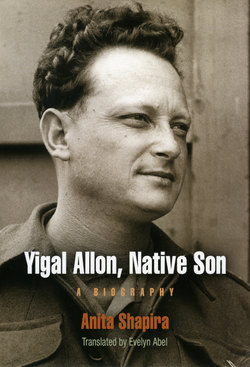

Figure 7. Yigal and Ruth Allon. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Allon family.

Ginossar took advantage of the eruption of WorldWar II on 1 September 1939 to further extend its vegetable tracts and planted fields. The pretext was that the emergency made it necessary to farm every bit of land lest wartime imports be stopped and/or the Arabs worked the lands and thereby gained rights to them.47

Up until that time, the Arabs of the Ju’ar village of abu-Shusha had used part of the waters of the Rabadiyeh spring and left the rest to flow into the Sea of Galilee. Like some of the village lands, the spring was the property of the PICA though the Arabs held it and Ginossar sought to obtain legal rights to it. The members of Ginnosar began by talking to the villagers and even reached an agreement: after the abu-Shusha lands were irrigated, the waters were to be channeled across Ginossar lands. But the Arabs broke the agreement and diverted the spring waters to the wadi on the approach to the village, from there to spill into the lake. The diversion was accomplished by placing a large rock in the channel to direct the flow. After the agreement was broken several times, the British stationed its Jewish Settlement Police (JSP) to guard the water.48 On 27 October 1939 a mobile, three-man JSP patrol was attacked. One member was hurt and his firearm was stolen. The guards shot into the air to raise the alert and call for help. A squad was organized at Ginossar with Allon (who had been recalled from Tiberias, where he served at Haganah’s headquarters) commanding the counterattack. At nightfall, the toll was three wounded Arabs and two dead, including abu-Shusha’s mukhtar himself—Sheikh abu-Fais Hamis, a notable landowner.

After the battle, the JSP guards among Ginossar’s members reported to the Tiberias police station to furnish an account of the incident. They said that an armed gang had assaulted the guards, that the others had rushed to their defense, and that the Arabs were hit in the course of the fighting, with one of the guards also wounded. Ten of Ginossar’s members were recorded as having taken part. Allon, who was no longer attached to the JSP, was not included on the record: had he admitted to possessing nonlegal arms, he could have faced life imprisonment or even hanging.49

Times were tense and confrontations between the Jewish Yishuv and the British authorities were frequent. The British had crushed the Arab Rebellion with an iron hand. But, at the same time, they embarked on a policy aimed at winning Arab goodwill or at least ensuring quiet by stymieing the development of the Jewish National Home. The White Paper produced by Colonial Secretary Malcolm McDonald and promulgated in May 1939 severely restricted Jewish immigration and purchase of land and announced the intention of his majesty’s government to establish an independent state in Palestine in another ten years, a state with an Arab majority. The transition from Jewish-British cooperation during the Arab Rebellion to Jewish-British confrontation entailed painful adaptation: it meant a change of tactics and going underground. The Ginossar affair slipped into these new relations. The routine report by and recording of the ten members at the police station now led to an official investigation, followed by detention and imprisonment in Acre jail to await court martial. Things looked grim: first, there was the fact of being tried in a military court rather than a regular one; and second, it soon turned out that not a single Arab suspect had been apprehended. Still, Ginossar’s members were not overly perturbed about the outcome: after all, it had been a clear case of self-defense, an incident like dozens of others that had taken place during the Rebellion. Nor was the Jewish Agency’s Political Department (JA-PD) especially worried, though it did engage the services of two top attorneys.

Allon was well-known to the villagers of abu-Shusha. Having lived his whole life among Arabs, he had been the natural candidate to negotiate with them on the spring water. In addition, he seems to have had friends in the village; according to one version of the battle, during the fighting, Mukhtar Hamis, who was later killed, saved Allon’s life by preventing shots from being fired at him.50 The villagers of Abu-Shusha swore that he had been among the assailants, but there was no corroborating evidence. At the trial, he served as an aide to the defense, especially on the military aspects: weapons, shooting, field movements, and so forth, details that were vital to the court proceedings but obscure to the lawyers.

In the end, the excellent defense of the able lawyers performed no magic and Ginossar’s ten members were sentenced to long prison terms. The verdict came as a shock: no one had expected a conviction or, certainly, so draconian a sentence. It was a harsh blow to tiny Ginossar, which was stripped suddenly of ten of its prominent, active members, including a core of its founders, among them Israel Levy and Yehoshua Rabinowitz, the farm manager and mukhtar respectively. In October 1940, Ginossar’s external secretary, Absalom Zoref, was also put out of commission. While walking in the fields near Acre in the hope of catching a glimpse of his jailed friends there, he came across three Arabs and was stabbed in the stomach. Zoref was laid up in the hospital for months before the wound healed.51 Ginossar was a ship without a helm, and Allon had little choice but to come to its rescue. Thus began his intensive period at Ginossar.

Allon was the key figure on the kibbutz for about a year and a half. One indication of his vital presence was a letter of protest dashed off by Israel Levy from prison to Ginossar when he learned of Allon’s recruitment for work with the Haganah (June 1940): “Ginossar’s plight makes it necessary for Yigal to play a role at home, and he, too, morally and socially, must fight to be available to the kevutzah in its special circumstances, nor can the [national] institutions ignore this demand.”52 In this period, Allon left his mark on Ginossar. It was the only time in his life that he was actively involved in the kibbutz.

The goal he set for himself was for the kevutzah to gain control of all the PICA’s lands not tilled by Arabs in the Jordan Valley. He began with a small step. One night, members of the kevutzah were recruited to plant 10 dunams (2.25 acres, 1 ha) of bananas, adding to the 200 or so sown dunams they had already cultivated. The PICA responded with a legal suit against Ginossar’s officials, including Allon. Public opinion, however, was with Ginossar. It granted the act legitimacy, which was symbolized by the fact that Hartzfeld spent the seder night of Passover 1940 with Ginossar’s prisoners in Acre, while the Labor leader and mentor Berl Katznelson chose to spend the holiday with the young kevutzah.53

As soon as the holiday was over, Hartzfeld wrote the PICA saying that, in view of the kevutzah’s courage and stamina, he could not accept its removal from the land; he suggested that the PICA resign itself to the situation, recognize Ginossar’s right to settle there, and even lease to it 600 dunams of Ju’ar land for the war period so that it could farm it legally.54 When France fell, and contact between the PICA’s executive in Haifa and its head office in Paris was cut off, Hartzfeld stepped up the pressure.55 The Haifa office refused to take responsibility without instructions from Paris, although it did agree to Ginnossar’s request to drop the banana suit.56 Allon had just promised the PICA not to venture beyond the 200 dunams cultivated by Ginossar, yet he immediately presented the members of the kevutzah with an expansion plan.57 The first stage called for constructing a concrete building, a sign of permanence, unlike the rickety shacks and tents that could be easily taken down. The pretext was security—a building to shelter children in times of emergency.58 To Allon and his friends, this was merely and clearly a further stage in the battle with the PICA, a test of how far Ginossar could go. Meanwhile negotiations proceeded with the PICA on formally regulating relations between them.

The PICA’s response was eventually forthcoming. Ginossarites spotted the PICA’s tractors overturning the soil around them, and they feared a plot. Had a Jewish settlement with no less right to the land than Ginossar reached an agreement with the PICA, leasing from it the lands that Ginossar believed should come to it? The fear was real and the settlement in question was the colony Migdal.

The PICA had in fact leased 250 dunams (62.5 acres, 25 ha) to Migdal. Allon now showed his mettle. Young and unknown, he nevertheless displayed leadership and resolve, calling on his powers of persuasion to recruit tractors from kibbutzim in the Jordan Valley. The tractors moved into action at the close of the Sukkot holiday, plowing all that could be plowed in the whole PICA area. The outcry was not long in coming: Ginossar, this time, had acted not against the PICA—which was naturally suspect in the Yishuv’s Zionist eyes—but against a small, poor colony. After much haggling, the two sides agreed to accept Berl Katznelson’s arbitration and the land was divided in two: the part on the west side of the road went to Migdal; the part on the east to Ginossar. The agreement was sealed on 2 December 1940 with the signature of Yigal Paicovich. Berl Katznelson’s handwritten endorsement in the margin gave it the weight of his authority.59

The affair highlighted some of Allon’s valuable qualities. He was eager to do battle with the PICA, which he appraised to have no fighting spirit. He was prepared to resort to piracy and subsequently to stand behind it.60 At the same time, he grasped the importance of public opinion and took pains to explain Ginossar’s position in the press and before the Yishuv’s institutions. He also showed an understanding of Migdal: in public he may have contended that it did not require the disputed lands; off the record, he acknowledged its real need. This, apparently, was one of the reasons that he agreed to compromise in contrast to his staunch and steady defiance of the PICA.61

The Migdal affair threw him into close contact with Berl Katznelson, one of the key Labor leaders. The determined kevutzah fighting for its right to till the land kindled Berl’s interest. He had most probably had a soft spot for Ginossar even earlier, for its refusal to join any single kibbutz stream and fiercely maintain organizational independence. Katznelson, campaigning at the time to unify all the kibbutz streams into one movement, felt affection and kinship for these young people who were actually living his doctrine. When, to add to their woes, ten of their members were arrested, as mentioned earlier in this chapter, he spent the 1940 Passover seder with them. He also helped them obtain a loan of P£200 to extend the irrigation fittings.62 His position reinforced Hartzfeld’s favorable attitude to Ginossar. Katznelson sought to untangle the mess with the PICA and apparently was also involved in the resumed negotiations between the two. And, of course, he helped resolve the conflict with Migdal, which could have damaged Ginossar’s public image.63

Katznelson’s special attitude to Ginossar is also seen in the role he played in another important step taken by Allon in those years. Allon decided to acquire a tractor for the farm, which, until then, had relied on mules and horses. His expansion plan entailed uprooting jujube shrubs that covered extensive areas. This called for a tractor. In addition, the tractor was a status symbol, the last word in progressive farming as opposed to the backward agriculture of cereal-based colonies. He found a new D-2 tractor—a feast for the eyes—at Tel Aviv’s Caterpillar agency, which was run by a man named Segal. But it cost P£200—a vast sum for Ginossar then. Allon, however, was not a man to be daunted. He secured a loan from an unknown benefactor: according to the same Segal, who ran the agency, it was he who lent the nice young man the sum.64 Allon never disclosed the source. In any case, the tractor was both a technological revolution and a boost for the morale. Still, the loan had to be repaid. Allon tried to obtain a loan at the Anglo-Palestine Bank, a cautious financial institution not in the habit of issuing loans to parties lacking credit and securities. He thus turned to Katznelson who interceded with the bank and won its agreement. But the bank demanded that the Histadrut executive underwrite the loan. Taking himself to the Histadrut offices, Katznelson convinced the treasurer Zalman Aharonowitz (Aranne) to serve as the guarantor. The said sum was P£160 and the kevutzah deposited a promissory note. The Histadrut executive signed on the note as guarantor. Signing for Ginossar—was Yigal Paicovich.65

Apparently, someone materialized to pay off the loan, for Ginossar never honored the note. It was left to gather dust in the Histadrut Executive files. But the main thing is that Ginossar had a tractor, and Allon had proved his ability to act in the world of the Histadrut leadership, which was not at all simple.66

The events only confirmed Allon in his estimation that the more the kevutzah created facts on the ground, the more they sapped the PICA’s opposition. In January 1941, a few months after the sizable land-grab and conflict with Migdal, Allon proposed to the kibbutz assembly that another 500 dunams of the PICA’s land be plowed, land still covered by dense scrub and thus untilled. The plan was carried out only eight months later. But it was typical that Allon had already charted this aggressive course in January, winning the support of his fellow members for the policy.67

Allon’s third important step at Ginossar was to set it on the road of affiliation with the KM movement. Ginossar, as stated, was established by youngsters trained at farms identified with Hever Ha-Kevutzot, the association of small kevutzot, such as Deganyah, which identified with the Mapai Party’s right wing.68 Yet members also had close ties with the secretariat of the HNHO youth movement, which pulled in the direction of the KM, Mapai’s left wing. The question of affiliation with a specific kibbutz stream had already surfaced in the early days at Migdal. The kevutzah clearly had to absorb new members, and members were to be had only from a kibbutz movement. The tension between the desire and need to enlarge and the fear that the newcomers would predominate over the founders—as had happened at several collective farms—led to internal struggles. The choice on the table was between the two streams of the Mapai.69 Israel Levy pushed for joining Hever Ha-Kevutzot lest HNHO trainees to Ginossar tip the balance in favor of KM. Most members were not yet ready for affiliation. They decided to keep their ties to the HNHO and through it to supplement their manpower on an as needed basis rather than attach themselves to any kibbutz stream at this stage.70 The kibbutz “neutralism” of the HNHO kevutzah at Migdal conformed to Katznelson’s banner of “uniting all the kibbutz movement” and was one of the reasons for the close relations between the veteran Labor leader and Ginossar’s young.

The KM movement apparently hoped that Ginossar would ultimately hitch up with it, though for the moment, it refrained from taking any action. Its great advantage over Hever Ha-Kevutzot lay in its large reserves of manpower. In the interim, it was not afraid to cast its bread upon the waters; it allowed German-Jewish youth groups trained at Tel Yosef—one of its kibbutzim—to join Ginossar.

The question of movement affiliation was discussed at length at Ginossar on the Jewish New Year of 1940. The advocates of association with KM were headed by Absalom Zoref, who supplied both ideological and practical reasons. To keep alive the collective idea—he argued—it was necessary to band together with other kibbutzim who lived by the same lights. Affiliation also offered agricultural training and support, manpower supplements, loans, and assistance with education and culture.71 In the ensuing show of hands, a large majority voted for affiliation; a small majority voted for affiliation with the KM. Since it had been agreed that a two-thirds majority was warranted to make a decision, the matter was deferred.

Allon had played a marginal role in the affiliation controversy until then. His friends thought that he did not really understand the language used by graduates of pioneering youth movements, that the fine differences between the various kibbutz movements eluded—and likely did not interest—him. Yet it was plain to him that the kevutzah was at a crossroads, in a transition from its days of genesis, with all of the hardships, uniqueness, and loneliness, to a spurt of growth. At this juncture, it was vital to obtain the patronage of a large kibbutz movement that could guide, advise, extend financial backing, and wield political clout in the institutions of the Histadrut.

Toward the end of 1940, Allon pressed Ginossar to come to a decision. The small kevutzah’s important members, led by Israel Levy, were in Acre prison as, in fact, were most of the founders still clinging to nonaffiliation. But the staunchest advocate of affiliation, founding member Absalom Zoref, was also neutralized and in the hospital. Allon took the bull by the horns and did what these members could not bring themselves to do: he made a decision.72 He, too, had a “red line” he would not cross; he would not countenance a split in the kevutzah. Nevertheless, he was more decisive than his friends in the old guard. He brought the matter to a vote without allowing further debate, tabling a motion to this effect at the kibbutz assembly of 30 November 1940: he said that because the members who were either in prison or in the Labor Legion in Sodom were unable to take part in the discussion, it was only fair that the members at Ginossar forgo influencing the outcome with further discussion.73 It sounded like the pinnacle of justice, but the fact was that the process of discussion had been exhausted and it was time to settle the issue. Of those present at the assembly, 80 percent voted to join the KM movement. The die was cast, and with a large enough majority to preclude resentment. This was no random majority foisting its will on a large minority. Ginossar was ripe for a decision, but it needed the resolute Allon to act as midwife.

As Ginossar’s official, de facto leader at the time, it was Allon who submitted the affiliation request to the Kibbutz Me’uhad Council (KMC) convening at Kibbutz Givat Ha-Sheloshah (17–19 January 1941). This was his first public appearance of any kind and it took place at a forum—the kibbutz council convention—that made it almost a tribal initiation, an outsider’s test of worthiness.

Allon chose to push through kibbutz affiliation at one of the most critical moments in the history of the Jewish Yishuv. On the war front, France had fallen and Britain stood alone fighting for its life, the same Britain that the Jews considered their ally, in whose army they wished to serve—and which treated them coolly. In December 1940, a few days before the convention of the KMC, the air was heavy with the drama of the Patria: the ship that was to convey to Mauritius in the Indian Ocean illegal immigrants—Jewish refugees who had made it to Palestine from Central Europe—was blown up. More than 250 immigrants were killed in the Haganah action that had been aimed at staying the deportation. The shock reverberated through a Yishuv divided between the action’s supporters and its opponents. A few days later, Jewish refugees from another ship, the Atlantic, were expelled to Mauritius amid a demonstration of British ruthlessness and Yishuv helplessness. The other power with whom the Left longed to identify, the Soviet Union, had also proved a disappointment: the alliance between Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany (the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of August 1939) was a stubborn blot despite all attempts made to explain it. Nor did Russia’s attack of Finland (December 1939) improve the image of socialism’s motherland. The KMC convention was overshadowed by a sense of the Yishuv’s isolation in Palestine and Jewish isolation around the world.

Most of the KMC convention was devoted to a report from members of He-Halutz, Poland’s Zionist pioneering organization that educated its members along the lines of the KM. The group had fled from the area of German conquest early on in the war and built up a fair pioneering movement in Lithuania. After some time, the Soviets allowed some of the pioneers “stuck” in Vilna to leave for Palestine and they finally arrived in the country after an adventuresome journey. The newcomers reported on the efforts to guard Jewish national identity against the assimilation onslaught by the Communist regime, on the strivings of pioneers to reach Palestine, and on manifestations of anti-Semitism in the land of the Soviets.74

For Allon, the deliberations were an eye-opener, a whole other world: “Those people showed me many new things about He-Halutz [members] that I didn’t know,” he later reported to the Ginossar assembly, adding somewhat patronizingly, “their fluent Hebrew is especially remarkable.”75 He learned “that of all the countries from which Eretz Israel absorbed pioneers, Poland took the most important place,”76 an admission indicating just how unfettered he was by knowledge of the KM’s social roots. Jewish experience beyond the boundaries of the Yishuv filtered down to him for the first time. True, he had been confronted with the question of immigrant Jews earlier: in March 1940 Ginossar had discussed absorbing a German youth group that was at Kibbutz Afikim, and he had defended the equality between immigrant and local youth against contrary opinions.77 But his stance on that occasion can be explained by his relationship with Ruth, herself a German Jew. At the KMC, the native son had to reflect on problems completely beyond his ken, from the trials of the Jewish people to ideological questions, such as the attitude toward the Soviet Union.

Though a stranger to the KM crucible, his impressions touched the heart of the matter: “At these deliberations I saw the element of mutual help between people who had reached safe shores and comrades living in the Diaspora. How sincere and caring the concern for them, as if it were one big family.” And he added: “I was especially moved by the promptness to discuss getting people out [of Europe] despite the perils.”78 He witnessed an inner solidarity diametrically opposed to Mes’ha’s individualism; a sense of collective togetherness, a devotion to this same large family that takes responsibility for its members but also imposes duties and obligations; and, finally, the dynamism of the KM as well as its eruptive self-sacrifice and all embracing sense of responsibility—all of this Allon felt instinctively in the council atmosphere, in the memorials that so impressed him, in the words of He-Halutz representatives.

His intuitive grasp of the essence of the KM, absorbed from the atmosphere and his immersion in that specific social, human experience, found expression in his public address on the KMC’s closing evening. He declared that Ginossar wished to join unreservedly, unquestioning of the movement’s ways or leadership. The kibbutz audience must have found this joyful conformism heartwarming: they already had enough rebels of their own, they needed no more.

In describing Ginossar’s settling on the land, Allon underscored aspects that could be expected to fall on eager ears. First, he emphasized the “redemption of the land” from Arab hands, reiterating this component and perhaps exaggerating its importance. With the exception of the incident of the “water war,” Ginossar had not seized any land tilled or claimed by Arabs. It had always been careful to take over land that was indisputably owned by Jews. The land-grab from the PICA and bringing the PICA to resign itself to the act were presented as a daring maneuver by young people on a mission to redeem national land, which, strangely enough, encountered resistance from the landowners.79 Second, the difficulties with the PICA, with the Agricultural Center, with the British authorities—Allon portrayed all of these as a character reference of excellence, making Ginossar fit for the KM.80 When, in summing up, Allon said, “We bring with us the deed, the deed of the KM: the building of a [settlement] point unassisted,”81 he displayed true understanding of the body to which he was seeking admittance.82

Ginossar’s acceptance to the KM was unanimous. The handsome, curly-haired Allon achieved fame and glory that night. Though his address suffered from stylistic shortcomings and might have benefited from a little “refugee” Hebrew, his articulation and grasp exceeded all expectations, especially as he had not been bred on youth movement traditions. David Zakai of the Second Aliyah, a member of Mapai and one of Davar’s veteran journalists, was so impressed that he mentioned the speech in his column of “Briefs” (21 January 41). He described a “fairly tall and bright-eyed youth … speaking with understated warmth and able humor of the internal and external hardships that found his group of friends … and how they resolved not to abandon ‘their Ginossar.’ …” It was Allon’s debut in the daily press.

Allons’ account to the Ginossar assembly of the KMC proceedings and of the commitment undertaken by Ginossar upon joining the KM movement contained a measure of zealousness and a demand for utter loyalty. It was the passion of the newly converted who had just seen the light.

It was his first political commitment as an adult, freely made. His need to show loyalty to the movement that had taken him in was to remain a lifelong habit. Loyalty to the kibbutz was not merely political, but total, of the kind one reserves for tribe and family. In such cases, disagreement or disobedience or a decision to leave takes on added meaning beyond narrow politics, and is judged in value terms as deviation or betrayal. The atmosphere of the KM held sway on many people, its leadership consciously cultivating it. On Allon it had a powerful effect, especially as he had come to the kibbutz without prior bonds. The lad who sold his father’s farm at Mes’ha and severed his childhood roots now found a new family ready to adopt him. It spawned in him a sense of commitment from which he would never break loose.

Several weeks after these events, Berl Katznelson invited Allon to take part in a month-long seminar he was giving in Rehovot. The wide-ranging symposium was to touch on history and Jewish philosophy, Hebrew literature, socialism, world politics, the history of Zionism, and the history of the Yishuv’s Labor movement. Participation was by personal invitation to people chosen by Katznelson as he saw fit and was based on his impression of their talents, openness, and leadership qualities. The KM frowned on Katznelson’s custom of circumventing its secretariat and approaching young members directly. The kibbutz lived by group decisions. It soon put pressure on the selected candidates to turn down the invitation, and quite a few did.83

Allon very much wanted to attend. The kibbutz assembly was asked to approve the absence of two members from Ginossar for the period of a month. Regarding one member, David Borochov, there was no problem. This was not so in the case for Allon: Allon was the secretary of the kibbutz and the farm’s functioning might suffer from his absence. Two key members were enlisted to support his participation: Absalom Zoref, who had just returned from the hospital, and Sini Azaryahu. Zoref explained the significance of Allon’s attendance: “He was among the last to be exposed to the movement’s basics and it is important that he take part in the course.”84 Sini stressed the added value to the kevutzah’s cultural life. Those arguing against Allon’s attendance made sure to note that though they were not envious, the good of the farm came first.85 The vote split, with thirteen in favor and fifteen against.

The vote notwithstanding, Allon did attend. For Allon, the seminar seems to have been his first exposure to any systematic, humanist education. Lecturers such as the Kabbalah scholar Gershom Scholem; the historian Ben Zion Dinaburg (Dinur), a future minister of education; the writer Haim Hazaz; and the intellectual Zalman Rubashov (Shazar), a future state president, unfurled before him a universe of which he had been ignorant, cultural riches whose lack he had been unaware of. In addition, the lectures by prominent figures from the Histadrut and Zionist movements—Ben-Gurion, Golda Meir, the KM leader Yitzhak Tabenkin, the Haganah head Eliahu Golomb, and so forth—had a great impact on him: horizons broadened, the world picture changed, the dimensions of reality expanded immeasurably. The seminar was dominated by Katznelson’s personality, Socratic charm, the founts of his knowledge, the idealism that oozed from his every pore, the inspiration that he was to his following. It is little wonder that the boy from Mes’ha, who only a few years back had still admired his village teachers, fell under a spell that had captivated men “mightier” than he.

Nor was Katznelson indifferent to Allon.86 Ever on the lookout for excellent youth with human and movement potential, Katznelson saw in Allon the qualities that caught his eye. He was intelligent, open, curious, thirsty for knowledge, handsome, and engaging. On seminar Saturdays and sometimes Friday nights, participants would get together socially and relate a life experience. Allon told of his path from Mes’ha to the kevutzah, and then of Ginossar’s wrangles with the PICA. He spoke simply, in plain language, to the point, both pleasingly and modestly. The fair youth, describing with resolve and self-confidence Ginossar’s land-grab, left a lasting impression on listeners as one of the seminar’s high points.87 Kibbutz activists had first noticed Allon at the KMC; in Rehovot, he came to the attention of Mapai’s leadership and young intellectual elite.

Amid all of these exciting events, Allon continued to apply himself to Ginossar’s affairs. One of the main tasks on the agenda was the speedy release of its imprisoned members. To begin, this meant reaching an accommodation with Ju’ar abu-Shusha by means of the traditional Arab sulha. A public sulha had been held in March 1940, a couple of months after the devastating sentence. The conditions were worked out, that is, gifts were awarded the families of the slain and other sheiks and notables involved, a black tent was put up at the site of the killing, and an offering was prepared with all of the trimmings—a festive meal of mutton cuts in bowls of rice. The ceremony was attended by envoys from both sides, by the regional governor, military and police officers, and ordinary dignitaries. When the guests assembled, the victim’s relatives stood and shook hands with Ginossar’s representatives, including with Allon, Ginossar’s mukhtar. They then placed a knotted kaffiyeh into their hands to symbolize the peace sealed between the sides. The bereaved family did not appear gratified by the procedures and had no stomach for the fare. Not so, the governor. In a valiant display of civic duty and unhampered by the absence of cutlery, he reached for the food to the glee of the gathered guests, their appetite in no way dampened. It was the first peace treaty concluded between a Jewish settlement and its Arab neighbors since the Arab Rebellion.88

In January 1941, Allon initiated a joint appeal from abu-Shusha and Ginossar to the military authorities asking that the prisoners be pardoned since calm had been restored between the parties.89 In May 1941, five of the prisoners were released, and in August 1941, the remaining five were released in a general pardon declared for prisoners of the Disturbances.90

On 9 February 1940, the Ginossar newsletter carried greetings from Absalom Zoref to Yigal and Ruth Allon on the birth of their daughter, Nurit. “Sorrow shared is sorrow halved,” Zoref wrote, jokingly alluding to the infant’s gender and attesting to the prevalent attitude to sexual equality. The child was lovely and her parents rejoiced. She was late to develop, but in a society of young, new parents, the warning signs went unnoticed. Only when she was two did the parents take her to a specialist, who diagnosed her as retarded. Their denial was typical of parents dealt so harsh a blow. She is so pretty! She sings so nicely, she says a few words! She repeats words over and over again, she repeats movements. The medical field at that time did not distinguish between the various forms of mental or emotional retardation and certainly had no solutions to offer. Nor could anyone tell the young parents whether the problem was genetic. For years, Ruth and Yigal Allon thus refrained from having any more children.

The severity of Nurit’s problems gradually became clearer. In these years, Allon was away a lot on security work and steadily achieving success. But he did visit a great deal and his letters are filled with deep concern for the child, his love for her, and his sense of helplessness. “I am so jealous when I see a child that says ‘Father,’” he confessed to one of the women at Ginossar.91 Nurit’s shadow stalked him through his most glorious triumphs, embittered his and Ruth’s life, and agonized them both. In public, Allon was the young success with the open smile; he was good-tempered and calm. But this image hid his wretchedness, heartbreak, and sense of impotence in the face of fate. There were two Yigals: the Palmah commander radiating youth, good looks, success, and sabra mischievousness; and Nurit’s father, hanging between despair and hope, between various treatments and different doctors, and finding no consolation. Allon’s ability to don a mask, to dissemble, developed in the wake of Nurit’s plight. His cheerful face did not mirror his heart, and it became his mask in times of both joy and sadness, so much so that it was difficult to get his real measure.

In this same period, 1941, Allon brought his father to live at Ginossar.92 The kibbutz circumstances had changed much in the preceding year as a result of its physical expansion, the advent of the tractor, and Ginossar’s admittance to the KM movement and concomitant financial aid. Helping parents now became feasible and Allon was among the first, if not the first, to bring his father to Ginossar.93 The old Paicovich had returned to Mes’ha in an attempt to recoup the farm that Allon had so thoroughly dismantled. But age and loneliness were against him. When he fell ill, his daughter, Deborah, took him home to live with her in Haifa. He was not fond of city life, however. When Allon suggested that he come live with him at Ginossar, he was pleased, although he wanted to make sure that Allon considered Ginossar his home and would not leave it: his heart would not stand yet another rupture, as both Mahanayim and Mes’ha had been.94 Yigal and Ruth Allon accorded Reuven half the shack at their disposal and they moved into a tent, an improvement as far as they were concerned over bi-family living quarters.95

As far as is known, Reuven did not complain about the living conditions at Ginossar. Nevertheless, it was a hard life: he was an old man living in a small hot shack without a toilet or other minimal conveniences and eating a diet that was sparse and inferior. Paicovich was not accepted as a regular member of the kibbutz but as a member’s parent. No one was interested in his advice or opinions. Lonely and unneeded, he wandered about the yard, grumbling in anger at the neglect. Toward the end of his life, he who had been a patriarch and a farm owner was expendable, necessary to no one. Allon showed him respect and treated him sensitively, but he was gone most of the time and old Paicovich had to make his own way through the maze of kibbutz society, which was young, foreign, and impatient. And he lacked the talent for it. His relations with his daughter-in-law were hardly warm: only an angel could win Paicovich’s heart, and Allon’s wife, the purloiner of his son, would likely have failed even if she had been an angel. It was Ruth who bore most of the burden of caring for him and quite naturally most of the resentment.

There was a dripping water tap next to the small shack and Reuven planted a eucalyptus seedling near it. The tree flourished and, one holiday, the kindergarten teacher brought her small charges to pick twigs for wreaths. Catching sight of them through the window, Reuven was enraged. He picked up a stick and went after the teacher and her wards, flailing about in all directions. Absalom Zoref, who was friendly with Paicovich and was sometimes summoned from work in emergencies to calm the old man down, was now sent for. “Mr. Paicovich, what happened?” he asked when he arrived at the shack. Paicovich had meanwhile cooled off somewhat, and for an answer he gave the tragic story of his life: he had had a dream, he said, to build at Mes’ha a village of Paicoviches. And, look, all his sons had left it and wandered far away. In the end, he had hoped that Allon would come build the farm. But this dream too was dashed, for Allon went to a kibbutz. This eucalyptus, he said, is a monument to his life’s dream, and monuments should be left alone.96

Whether or not Allon acknowledged the calamity he had brought down on his father and the misery he had sentenced him to is a moot question. To the extent that Paicovich could show warmth, their relations remained warm and close. With his other sons, he refused to keep in touch, barely agreeing to spend the Passover seder with them in the year that Allon was out of the country. The sons contributed to Paicovich’s upkeep on the kibbutz, though this remained unknown to him lest he balk.97

In early 1942, there was a sense of relative prosperity at Ginossar. The jujubes were uprooted by a powerful tractor and the newly exposed 500 dunams of arable land were plowed. The work began on the day that the second batch of prisoners was released. Within a few months time, Ginossar’s cultivated area doubled. Now, since the authorities encouraged intensive agriculture, Ginossar applied for a government loan to install irrigation. It received P£2,000 and in 1942 it erected a water plant.98 The PICA was flummoxed. Every fact the members created on the ground increased Ginossar’s holdings and challenged anyone to try to evict the residents from their homes. The living conditions did not improve: the farm’s flourishing did not translate down to the individual level. Spot checks by the health fund doctor still resulted in alarming sanitation reports. The daily per capita budget stood at 37 mil. Dirt in the kitchen and dining hall made visitors cringe, as did the overcrowding. As for the levels of cleanliness and services in the laundry, the dairy, the showers, and the toilets—the less said the better.99 Family living quarters were still unbearable. In vain did the doctor issue warnings about epidemics. Ginossar’s members were preoccupied with other things.100 The most important of these, with the exception perhaps of building a new children’s house, was the farm’s expansion. In 1943 a group of parents in Tel Aviv organized to help Ginossar by paving a road to the kibbutz—in members’ eyes, a wasteful luxury. The plan was to raise some P£400 from parents “of means” with the contractor doing the work providing the remainder as a loan.101 It is not clear if the plan was executed. The idea, however, expressed both parental anxiety at Ginossar’s isolation and confidence in the permanence of the settlement site.

In October 1942, the PICA’s director, a man named Gottlieb, arrived from France, and a new exchange of letters began with Ginossar.102 This time, other personalities also entered the picture, such as Henrietta Szold, Norman Bentwich, and Hans Beit, the latter two being directors of Aliyat Ha-Noar (Youth Aliya), which brought refugee youth to Palestine. An attempt was made to enable the kevutzah to remain where it was while assuaging the PICA’s injured pride. At the end of 1946, a formula materialized—Ginossar was to publish a public apology. Thereafter, the talks revolved around the sum of compensation due the PICA for ten years of Ginossar’s unlawful use of the lands.103 Eventually, the sum of P£6,000, was agreed on, to be paid out in installments. On 22 December 1947 the daily press carried Ginossar’s apology for having settled land “intended for other settlers” without permission from and in disobedience to the PICA. “We hereby express our regret for our past actions and also ask for the PICA’s pardon for [things] we publicized that later turned out to be inaccurate.”104 The PICA book was closed. It is not clear if Ginossar in fact made the payments. The compensation was presumably forgotten in the upheavals of the War of Independence. Ginossar’s young were vindicated, their stubbornness and impertinence had held out against a bureaucratic, legalistic, and stodgy institution. Not only did they emerge with Ginossar in their possession; they even managed to mold Yishuv public opinion in their favor. The PICA came to be seen as a failing settlement agency, obtuse about the demands of the national good.

The epilogue was still to come. In 1952, Yigal and Ruth Allon, who were in England, were invited to the home of Baron James de Rothschild. Allon, basking in the glory of the War of Independence, took the opportunity to lay before the baron both Paicovich’s and Ginossar’s complaints about the PICA’s officials. The Palestine officials, it emerges from the documentation, did not act independently; the baron had been well aware of what had been going on even if he had not been directly involved in the details. Nevertheless, both the host and his guests found it convenient to regard the officials as the root of all evil. Following the conversation, the PICA modified its attitude to Ginossar.105

In November 1941, the poetess and future paratrooper to occupied Hungary, Hannah Szenes, spent some time at Ginossar and wrote down her impressions:

I see in the society a number of advanced people among whom I’m sure I could find interest and friendships; although the society as a whole is not spirited enough I still have the impression of a good society. More precisely: [it is] a society made up of many good individuals but devoid of a social voice. This lack is expressed in all common areas from the reading room to the general assembly … a considerable number of members are certainly missing a clear collective awareness, their ties to the kibbutz [are] love of place, a simple social bond. They feel good here, factors that can sometimes hold a person at a place better than any awareness, but they are not promoting or developing society life sufficiently or in the desired direction.106

Hannah Szenes seems to have hit the nail on the head. Her assessment was true not only of most of Ginossar’s members, but perhaps of most of the youth who went to kibbutzim in those days. It was certainly true of Allon. Ginossar was the first stage in his education, assimilation, and internalization until the movement that adopted him became an integral part of his personality. It was a process that began in the years of his apprenticeship at Ginossar.

From the end of 1941 onward, Allon’s work at Ginossar dwindled more and more. On 9 February 1942, Ginossar advised the district officer in Tiberias that Yigal Paicovich had ceased to serve as mukhtar due to an illness warranting a lengthy hospitalization.107 Allon was having problems with his shoulder as a result of a run-in with a cow while riding a motorcycle on Haganah duty.108 The unromantic encounter had occurred in May 1939, leaving his shoulder dislocated. The illness referred to in the letter, however, seems to have been of a conspiratorial nature, for only in June 1943 did he undergo the necessary surgery.109 From February 1942 onward he was busy with ventures best kept under wraps at the time. From this stage onward Ginossar occupied an important place in his and his family’s life but his absences outstripped his presence there. His vitality was given to security affairs.