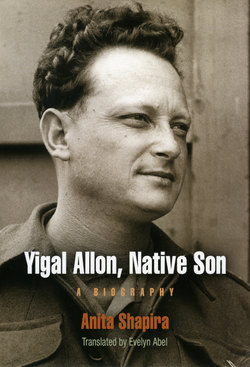

Читать книгу Yigal Allon, Native Son - Anita Shapira - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

Last Rites

Yigal Allon was the man and mark of a generation: the generation bred in Eretz Israel during the struggle for Jewish statehood. This book is dedicated to him and his era, when he and his peers in the elite Palmah fashioned the country’s first youth culture, setting the tone for those who came after.

“Palmahniks” were neither highbrow nor cultivated but a young brigade of daring volunteers. Apart from a handful of writers and poets who sprang up from within, most had little use for the trappings of culture or social graces. And yet their defining experience, which was to stay with them throughout their lives, became the cultural inspiration of the young. The type of person spawned by the Palmah was not without fault. There was about them a callow rawness, an upstart’s brashness, the shallowness of men of action, the intolerance of the self-absorbed. They judged both themselves and others mercilessly, knowing no compassion. Yet they were also capable of openness and high-flying idealism, extraordinary acts of friendship and comradeship, reticence and loftiness, humility and dedication. They had a measure of pride that in their youth took the form of arrogance and over the years was widely translated into independence and self-sufficiency, a personal autonomy, so to speak. Many of the Palmah veterans flowed with the times, changed their lifestyles, forgot the ideals of their youth. All, however, retained that core sense of belonging and fellowship formed on those heady, faraway nights of campfires, coffee, and song. Those who detached themselves from the past were spared the anguish of recent decades when the old kibbutz order collapsed, taking with it values that had been the bedrock of their lives.

Others, such as the Palmah’s erstwhile intelligence officer, Zerubavel Arbel, never resigned themselves to the change. In an interview I had with him at Kibbutz Maoz Haim in order to write Yigal biography, he described, with wonder and wistfulness, the yawning gulf between himself and his father, whom he held in affection. The intellectual parent, a teacher at the historic Herzliya High School, and the son, who had built the IDF’s field intelligence, were separated by an unbridgeable chasm of lost Jewish culture. The father was vastly more educated; the son was far handier in physical wisdom and the lore of action. Theirs, in microcosm, is the story of the generation gap between founding fathers and native sons in the land of Israel. It was the native sons and their devotees who shouldered the task of establishing the state of the Jews.

Arbel, like many Palmahniks, loved the land of Israel with his very fiber, knew its every wadi, its every groove. The Bible occupied a place of honor, and he read it like a guide book for its history and geography. He led me to a lookout over the Jordan Valley to point out the route taken by the Jabesh-gileads on their way to Beisan (Beit She’an). The biblical story is brief: the Philistines came upon the bodies of King Saul and his sons, slain in the battle on Mount Gilboa. They cut off Saul’s head, stripped him, and hung him and his dead sons on the walls of Beisan. When the news reached the men of Gilead across the Jordan River, they walked all night long to Beisan, took down the bodies, buried them in their own land, and fasted for seven days. They had never forgotten the young Saul’s goodwill when he saved them from Nahash the Ammonite. For Arbel, this final kindness, the last rites the Gileads performed for Saul, was a founding myth: again and again he would gaze at the route the Gileads took that night, cherishing their noble gesture to a defeated king fallen on the sword. For Allon, too, the story of Saul was a central motif. He loved the biblical character who had begun life like Cinderella and had ended it like the hero of a Greek tragedy. It was the tale of a lad towering head and shoulders above his people, worn down by political squabbles, by a savagery and chicanery he could not deal with. Was Arbel intimating that Allon’s fate was a modern version of Saul’s tragedy? Perhaps he was underlining the importance he himself attributed to a biography of Allon—the last rites for a dead commander who in his youth had delivered the people of Israel and won the hardest of Israel’s wars.

I chose not to tell Allon’s whole life story but only his story until the end of the War of Independence, the “War of Liberation” as that generation called it. The war was a watershed between Yishuv society and statehood. Whatever the continuity between them, the Yishuv and the state represented totally different human, social, and cultural entities. The main account thus stops in 1950 with the conclusion of Allon’s military career. It was the end of an era both in his personal life and in Israeli realities. It was the end of one era, and the start of another.

Allon’s story is not about the victors of a historical narrative but about those consigned to oblivion in Israel’s public discourse. Those who perished on the upward climb without making it to the top also deserve a voice in collective memory. For without the story of the forgotten, history would be incomplete. This book stands as the last rites to them, the fallen of the first generation of native sons.