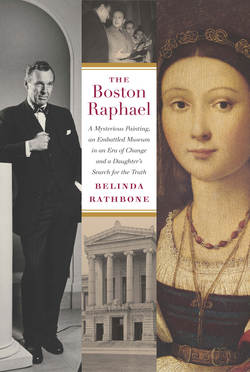

Читать книгу The Boston Raphael - Belinda Rathbone - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe Centennial Looms

IN THE MID-1960S the Boston Museum of Fine Arts approached its 100th birthday. Like many great cultural and educational institutions in America, the Museum was an offspring of the Gilded Age, an age of enormous wealth enjoyed by a very few that was the bedrock of its formation. In 1870 the Museum was conceived by a group of high-minded Boston Brahmins and incorporated as “a gallery for the collecting and exhibiting of paintings, statuary, and other objects of virtue and art.” Six years later its first dedicated building opened on Copley Square with its fledgling collections of paintings, plaster casts of classical statuary, and real Egyptian mummies. Well-to-do Bostonians were inspired to give generously to their new Museum, and the collection quadrupled over the next decade, leading to the concept of a new building site on the parkland of the Fens. Over the years it consistently surpassed the ambitious goals of its founding fathers, but by the 1960s it faced an ongoing financial struggle to maintain the high standards it had achieved. Therefore, it was essential to make the most of its forthcoming landmark year, to publicize and celebrate its greatness, and also to make known its pressing needs. Meanwhile, in New York, the Metropolitan Museum had a brand-new director, the youthful and dashing Thomas P. F. Hoving, and the Met was gearing up for its centennial celebrations the very same year.

The rivalry between New York and Boston, and between the MFA and the Met in particular, was age-old. Born just two months apart, they were from quite different backgrounds, and each had strengths the other envied. The MFA, as historian Nathaniel Burt wrote, “inherited a collection, prestige, the backing of Boston’s Best and its best institutions, everything but public assistance and cash.” From the beginning, Boston, compared with New York, was “scholarly, intense, serious, but poor . . . a long thread of complaint weaves through the rivalry of the two sister institutions, the Met always jealous of Boston’s reputation, and Boston always jealous of the Met’s money.”1 Boston’s collection of Japanese art was unrivaled anywhere in the world (including Japan), and those of ancient Egyptian and classical art second only to the Met’s, and in some areas even greater. But the Met had the noticeable edge in old master paintings, and in the eyes of the general public, that was what mattered.

These comparisons were in high relief as their centennials approached, especially with Hoving and Rathbone at the helms, both known for their bold outreach and flair for publicity. While Rathbone was a seasoned museum director now in his midfifties, Hoving was twenty years his junior and in 1967 new to the directorship of the Met, immediately following a brief stint as parks commissioner under Mayor John Lindsay and, earlier in his career, a curatorial assistantship at the Cloisters, a medieval branch museum in Fort Tryon Park. Rorimer, another medievalist and Hoving’s immediate predecessor as director of the Met, had guided the Met for the previous eleven years. He was distinguished by his connoisseur’s eye for quality and his expert hand at installations. But he was socially insecure, secretive by nature, and remained aloof to most of his staff as well as the general public. “Rorimer had a passion for professional anonymity and secrecy,” wrote John McPhee. “He had an air of cloaked movements and quiet transactions, of indisclosable sources and whispered information – a necessity surely in the museum world, and something that Rorimer had refined beyond the wildest dreams of espionage.”2 He was also not very collegial, and Rathbone had never warmed to him.

In their choice of Hoving as Rorimer’s successor, the Met trustees sought to embrace a larger public, a museum more committed to education and outreach. The Rorimer years were ones of “consolidation and careful management,” according to museum historian Calvin Tomkins, but now it was time for a leader more inclined to innovation, someone more like Rorimer’s predecessor, Francis Henry Taylor, who had boldly moved the Met out of its postwar doldrums. “The pendulum had swung once again,” wrote Tomkins of Hoving’s appointment. “Youth and energy and fresh ideas were at a premium, and the soundest policy might well lie in the calculated risk.”3

Hoving and Rathbone were both native New Yorkers, but from different parts of town. Hoving was born to privilege – his father was chairman of Tiffany & Co. – and young Tom grew up in a spacious apartment on Park Avenue, attended private schools, and summered in fashionable Edgartown. Rathbone was the penurious son of a wallpaper salesman from Washington Heights, attended public schools, and spent his summers at his grandmother’s house in the sleepy upstate village of Greene, New York. But while there were differences in their backgrounds, their personalities shared the essential traits of the modern museum director: a natural instinct to popularize and to publicize, and a readiness to perform for the crowd, the camera, and the microphone. “A foe of stuffiness,”4 as the press described Rathbone when he arrived in Boston in 1955, was a term that could equally have applied to the young Tom Hoving twelve years later. As historian Karl Meyer put it, Rathbone was “an older and tweedier version of Hoving.”5

Rathbone was older, but tweedy would hardly describe the image he projected in his portrait by photographer Yousuf Karsh in 1966, which shows him as he typically presented himself – perfectly groomed and meticulously dressed, with a flair that walked the line between conservative and sporty, a casual, colorful elegance that is the museum man’s special turf. Six foot two and weighing in at an approximately maintained 180 pounds, he understood the language of clothes, the quality of materials, and how to strike a pose. Stylish as he was, Perry Rathbone did not give off an air of privilege as much as pride in his role in serving the public. Despite, or perhaps because of, his privileged upbringing, “Hoving didn’t have the class that Perry had, or the elegance,”6 according to the art dealer Warren Adelson, who knew them both.

Hoving was something of a bad boy, capricious and unpredictable, a natural show-off. Rathbone strove to make people feel comfortable, while Hoving rather enjoyed making them squirm. Both Rathbone and Hoving had an appetite for challenge and a high tolerance for risk. But Rathbone was also a stickler for accuracy, while Hoving was perfectly comfortable with the occasional white lie or colorful embellishment of the truth. He brought to the director’s job a dash of the high-end salesman, with that hint of condescension, along with the savvy of a city politician. These were interesting ingredients, and perhaps just the ones needed to dodge the bullets that would certainly come flying before he was through with the Metropolitan Museum, and it with him. In retrospect, Hoving was perhaps better prepared than Rathbone for the changes that were then taking place in the museum world, and more adept at directing them to his advantage. As the directors lined up for their banner year, it was going to be an interesting dance to watch.

In 1965 Rathbone began the monumental task before him, to “lay pipe” for 1970. A centennial, as some wise person told him as he entered the planning stages, is a fate worse than death. By the time it was over, he would come to understand the full weight of those words.

For the first time in its history, the Boston Museum embarked on a capital campaign drive. Looking forward to its second century, securing the funding was a foremost priority in achieving its goals. In the 1960s inflation was changing the economic outlook in ways that no one could have predicted, and in ways that made everything going forward unpredictable. The museum’s endowment went down, while the pressures on its financial resources went up. The cost of mounting exhibitions was suddenly many times what it had been just a few years before, with insurance, travel, and construction costs rising exponentially. At the same time it also began to be clear that professional curators could no longer afford to live on the modest “gentlemen’s” salaries that used to be par for the course. There was the high cost of living, and there was the high cost of running a museum. Until recently the Museum’s endowment had paid for 90 percent of its operating expenses. Just as the public’s expectations climbed, inflation outpaced the endowment revenue. Just as the American public was becoming accustomed to the idea of improvements in every sector of public life as an inalienable right, the postwar economy began sputtering for the first time.

Architectural rendering, George Robert White Wing, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1969.

The biggest challenge was the need for space; with its increased staff and operations developed under Rathbone’s direction, the Museum had outgrown its building. A whole new wing was conceived to expand and improve its activities. At a projected 45,000 square feet, this new wing would increase exhibition space and relocate the administrative offices, library, restaurant, and education department. Physically it would join the two extensions at the west end of the building to form an outdoor courtyard for the display of modern sculpture.7 Phase one of the program was to add additional space to the decorative arts wing at the East end to house the Forsyth Wickes collection in meticulously reproduced interiors of the benefactor’s home in Newport, as specified by his will.8

Beginning with the urgent need to publicize the campaign, Rathbone moved the versatile and affable Diggory Venn over from the education department to direct the production of fund-raising materials and generally field all publicity efforts. The Challenge of Greatness, a lavishly illustrated booklet, detailed the Museum’s needs, breaking them down into their various categories: bricks and mortar, staff salaries, operations, and last but not least, acquisitions. After a long trustees’ meeting in October 1965 to discuss fund-raising tactics ahead, Rathbone recorded in his journal the reluctance he faced in introducing the bold facts of raising money to the Yankee old guard. Clearly, they had come to take their museum’s financial health for granted, to believe that they were well set up for the future, thanks to the generous and farsighted founders of the pre-graduated income tax days. As Rathbone discovered to his dismay, “There was a conspicuous dislike of the direct appraisal of what our trustees must give.”9

A few days later Rathbone’s mood was more optimistic, following the first “cultivation” meeting for the Centennial Development Fund Drive in the ballroom of the Sheraton Hotel in Copley Square. Helen Bernat, a new trustee with fresh energy, had arranged a luncheon party for a group of prospective donors and guests of honor, including Senator Edward Kennedy, Boston mayor John Collins, and William Paley, chairman of CBS. “A bit of a strain for all concerned,” recorded Rathbone, “but anxiety melted with the success of the proceedings. Mrs. B. spoke beautifully and president Ralph Lowell was at his best. Then a slide presentation with a tape recording followed by my speech which went over very well. We are encouraged. For the first time outside the Museum family I pronounced our need – $20,000,000.”10, 11 In 1965, when a first-class postage stamp cost five cents, the Eastern shuttle between New York and Boston was fifteen dollars, and an average family income was less than $6,000 a year, this was a breathtaking figure indeed.

When Rathbone took the helm in 1955, the MFA was widely known as the Old Lady of Huntington Avenue – respected, staid, rich, but old-fashioned. The trustees knew full well that the Old Lady had fallen behind the times, and she required a major fix. Arriving straight from his conspicuous success as director of the City Art Museum of Saint Louis,12 Rathbone appeared to be the kind of man the Museum was looking for to charge the place with new energy and fresh ideas.

Since 1935 George Harold Edgell, who was also one of Rathbone’s professors at Harvard, had been director, but his instincts for running the Museum remained stalled in a Depression-era attitude. “Charming and cavalier,”13 as Rathbone described him, Edgell arrived at the MFA every day with a pet spaniel that slept under his desk and checked out early on Fridays to head for his shooting estate in New Hampshire. About once a week he made the rounds of the curatorial departments to inquire if there were any letters that needed writing. Otherwise it seemed to him there was little left for him to do and no conceivable way for him to improve on the peaceful status quo. Legend had it that museum attendance was so low that Edgell and William Dooley, head of education, used to stand at the Huntington Avenue entrance and wave their arms in front of the sensor to raise the figures. Special events, such as the afternoon tea parties that quietly honored the installation of a corridor of drawings, were attended by a loyal and mostly elderly few. MFA trustee Richard Paine, an innovative investment advisor, told Rathbone in all candor that he hoped under his directorship there would be no more of those parties that no one turned up for except “some old ladies in funny hats.”14

The job Rathbone was taking was on an entirely different scale from the one he had left behind. The Boston Museum was considerably older than the City Art Museum of Saint Louis, and its collections far more extensive. While the Saint Louis museum had just one curator to cover all departments,15 every department at the MFA was led by an aging curator, each one internationally revered and firmly entrenched, each in charge of his or her own little hill town. Furthermore, in contrast to the Saint Louis museum, whose operating costs were entirely supported by city funds, Boston had the only major museum in the country entirely dependent on private donations – not a single tax dollar headed its way. In the mid-1950s there was no admission charge, and Rathbone was appalled to learn that the Museum had only fifteen hundred members, nearly half of whom paid less than five dollars a year for the privilege. Meanwhile, the staff of the Museum operated a little like a men’s club, in which its curators, as well as its patrons, carried on their work with virtually no accountability to their public. The collections were priceless, but the Museum was nearly bankrupt, and the galleries were dim and lifeless. It was, as Rathbone described it, “a slumbering giant.”16

Boston’s challenges were clearly visible in the mid-1950s, but there was at least one factor making the job more attractive to Rathbone than Saint Louis had been at first.17 The Museum had a congenial and gentlemanly president of the board, the white-whiskered Ralph Lowell. Lowell was the quintessential Boston Brahmin. “Mr. Boston,” as he came to be known, sat on many boards in the city, where he performed the duties of the civic-minded philanthropist. Lowell was the opposite of a social climber, sitting with his wife, Charlotte, at the top of the social ladder and, in typical Boston style, dressing the part down. Personally he seemed to see no reason to change his habits as progress crept up around him – he never learned to drive, and he never flew in a plane. He summered in Nahant, a quiet spit of oceanfront a few miles north of Boston, and not once in his life had he set foot in Newport, that ostentatious getaway of rich New Yorkers. But while firmly habit-bound, Lowell was not so conservative when it came to the evolving needs of the cultural institutions he served in Boston. Practical and to the point, he instinctively understood the pressing goals and needs of the MFA at midcentury. By the time Rathbone came to the helm, Lowell, like other members of the MFA board, was ready for change. For his part, Rathbone understood that enlisting and maintaining the support of the old guard was implicit in his appointment as museum director. He would have to go about his job with a sense of respect for tradition while remaining alert to the challenge of delivering the changes everyone understood were necessary for the MFA.

Indeed, the careful investigation of Rathbone’s suitability had been going on for months, if not years. MFA trustee John Coolidge had visited Saint Louis two years earlier and had returned with a very positive impression of the art museum – a grand neoclassical edifice designed by Cass Gilbert for the 1904 World’s Fair as a Hall of Fine Arts, situated at the highest point in the city’s sprawling Forest Park. Coolidge, then director of Harvard’s Fogg Museum, found the Saint Louis museum “full of stimulating surprises, no duds with big names . . . but always fresh, unpretentious, and truly wonderful.” He credited the director with its extraordinary growth and winning style. “Rathbone’s showmanship is exemplified by his placing of sculpture and tapestries. He has adapted an intractable building, a monument, to diverse uses, and he has expressed the highest connoisseurship and taste.”18 The trustees of the MFA were at the time beginning to wonder when their aging director Edgell, now in his seventies, would retire and could hardly wait to move forward with the search for his replacement. Several other candidates were considered, including Rathbone’s Harvard classmates Charles Cunningham, who would soon take on the Wadsworth Athenæum, in Hartford, and James Plaut, director of Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art. Also under serious consideration was Richard McLanathan, already curator of decorative arts at the MFA. But while all were equally Harvard men (imperative) and graduates of Sachs’s museum course (desirable), Rathbone had the edge.

Perry T. Rathbone watches visitors’ reactions to medieval limestone sculpture of the Madonna and Child in sculpture hall, City Art Museum, Saint Louis, 1952.

In their selection of Perry Rathbone for Boston, some trustees may have been impressed by his circus-act publicity stunts, which were certainly notable (it was said he had more in common with P. T. Barnum than his first two initials). Exuberant – irrepressible, even – he never failed to dream up some colorful surprise to draw the public’s attention to the latest museum event. But even more to the point, Ralph Lowell cited the number of special exhibitions he had organized that were indeed worthy of the fanfare. The era of ambitious loan shows was just beginning, and Rathbone was a clear leader in the movement, with the extraordinary success of his exhibitions from postwar Europe that, although the term had not yet been applied to the art museum, were blockbuster events. In January 1949 searchlights spanned the dark midwinter skies from the top of Saint Louis’s Museum Hill to announce the exhibition of Treasures from Berlin, a spectacular display of old master paintings that had been buried in the Merkers salt mine during the war. The crowds came in droves – some from hundreds of miles away – with lines of automobiles clogging the roads through Forest Park to the entrance of the Museum. To accommodate the unprecedented crowds in a limited schedule, Rathbone pressed the city to provide special bus service and kept the doors open twelve hours a day, from 10:00 a.m. to 10:00 p.m. When the one hundred thousandth visitor passed through the entrance gate, the director was there to greet the astonished young woman with a gift. To this day no exhibition in the history of the Saint Louis Art Museum has topped the attendance record set by the Berlin show – an average of 12,634 people per day.

Perry T. Rathbone escorts Eleanor Roosevelt into Treasures from Berlin, City Art Museum, Saint Louis, January, 1949.

Just two years later Saint Louis would host another blockbuster. The Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna sent 279 works of art from their collection on a tour of American museums. Many of the works of art, including the famous Gobelin tapestries, were on a spectacular scale, and twenty-one galleries on the ground floor were cleared to accommodate them. Treasures from Vienna also included a number of pieces from the Hapsburgs’ world-class collection of arms and armor, and Rathbone’s publicity plan drew special attention to this feature, arranging for a knight on horseback to parade through the streets of downtown Saint Louis to advertise the show and later entertaining visitors when they arrived at the Museum. Again attendance hit record highs, altogether 289,546 over a six-week period, which, according to one report, was 90 percent higher than the crowds for the same show when it traveled to Chicago.

In addition to this exotic fare, Rathbone conceived and created exhibitions of American art that spoke to the regional interests of the southern Midwest, such as the popular Mississippi Panorama and Westward the Way. Consistently, he also championed modern art and local collectors, most notably the newspaper heir Joseph Pulitzer, Jr., the department store mogul Morton May, and the symphony orchestra conductor Vladimir Golschmann, thereby encouraging many other Saint Louisans to join in the excitement of collecting art of their own time. Perhaps Rathbone’s greatest personal achievement was to mount the first retrospective of the art of Max Beckmann in America in 1948.

Rathbone had landed in Saint Louis right at the cusp of an era of change, and he had succeeded in transforming the museum from a quiet repository of art into a vibrant center of culture, attracting people from every walk of life. With a broad mind and boundless energy, he seemed capable of anything. News got around the country that there was a man in Saint Louis who could, and did, make the difference. With his instinct for publicity and his eye for quality, he seemed a person who could lead Boston into the future. “He’d made quite a splash in Saint Louis,” recalled one MFA trustee. “He was clearly a man who had a high level of ambition. He also had a great success at breaking some of the original boundaries of what a museum might be. It was very exciting.”19

For Rathbone’s part, it was a tortured decision to pull up stakes in Saint Louis, where his career had taken off, where he had formed enduring friendships, and where his happy family life had begun. But it was obvious that Boston’s offer meant an advancement to his career, and so with excitement and resolve he accepted their offer in 1954. Francis Henry Taylor, the then recently retired director of the Metropolitan Museum,20 sent a telegram to the MFA’s board of trustees congratulating them “on securing the best man in the country.”21

Ten years later, Taylor’s description was borne out – the MFA had rallied from its slumber, and from all appearances, Rathbone, its first professional museum director, was living up to the board’s highest expectations in every way. If some of the older guard had been wary of this young man from the Midwest, they could by now hardly deny his positive effect. He had instilled logic and clarity into the organization of the collections on view, and excitement into their display. To the MFA’s “stifling” and “airless” galleries Rathbone had brought a “fresh breeze,” said many a press review of the new director. He had “ventilated” the place with new energy and a new kind of economic prosperity, one that relied on the engagement of a broader public and the stimulation of a declining urban population. In his centennial history of the Museum, Walter Whitehill called Rathbone’s initiatives “The New Deal.” He cited Rathbone’s combination of “rare artistic perception and knowledge with the instincts of a showman,”22 the qualities that made this “New Deal” a reality.

Under Rathbone the MFA immediately took on a distinctly festive spirit. While the director set forth to make the museum building and collections more attractive to visitors, the Ladies Committee, under Frannie Hallowell, fanned out all over Boston and environs to drum up new members, from Newburyport to the north, New Bedford to the south, and Framingham to the west. Long gone were the days when everyone who might have cared for the Museum lived in the Back Bay or Beacon Hill; like most American cities after the war, Boston had fled to its suburbs. Furthermore, ethnic pockets of Greek, Italian, Irish, Jewish, Polish, Armenian, and Chinese needed to be actively sought out and convinced that the MFA was not for Brahmins only. As the old saying goes, Boston was a city where “the Lowells speak only to the Cabots, and the Cabots speak only to God,” but it was time for those conversations to broaden and for those barriers to break down. The Ladies Committee went about the task of ensuring they would.

Opening receptions at the Museum under Rathbone were among the most sought-after social events of the season and always well covered by the press. Hallowell and her band of ladies made every affair a memorable one, showing the same playful passion for surprise tactics for which the director had become famous. They decorated the grand staircase, designed the dinner menu, and created party favors according to the theme of each new exhibition. A fife and drum corps of men and boys led the guests into dinner for the opening of paintings by John Singleton Copley. For The Age of Rembrandt, the Ladies arranged Dutch floral still lifes complete with real birds’ nests and bugs in formaldehyde. For Chinese National Treasures, they created twin dragons – a spectacle of wire mesh and evergreen clippings writhing their way down the main staircase. Rathbone could now rest assured that with the Ladies in charge, there would be plenty of drama and excitement without the need to conjure up the circus acts of his past (and which had sometimes run away with him).23 No more “old ladies in funny hats.” The MFA had become the place to see and be seen.

It was also a place where the staff loved their work, where they felt appreciated at the top, no matter what their position in the hierarchy, for the director conveyed a sincere interest in each one of them personally. “Just the way he said hello in the morning made me feel good for the rest of the day,” remembered long-time staff member Carol Farmer of Rathbone’s leadership. On the job, Rathbone was never one to hole up in his office; he was all over the Museum, moving through the galleries and offices at a brisk clip, addressing every staff member he encountered by his or her first name. This was not only a friendly spirit but also one that constantly showed his passionate interest in the high standard of every link in the complex chain of the Museum’s management. Every December a bibulous Christmas party was held for the entire staff, which by the mid-1960s had grown to four hundred. While many Boston-area institutions and businesses had begun to phase out the Christmas party as an unnecessary extravagance, the MFA staff fondly adhered to its traditional festivities, where the spiked punch flowed freely, musicians inspired all manner of dancing, and scholarly curators broke into song. On a more regular basis Elizabeth “Betty” Riegel, the head of the sales desk, held an informal sherry hour in the gift shop every Friday afternoon at five o’clock as her way of marking the end-of-week balancing of the books. Rathbone often dropped in for Riegel’s sherry hour, and many other staff members were regulars as well. These were the gestures that buoyed morale in immeasurable ways and reinforced the feeling that every constituent was a member of the team.

Virginia Fay, Santa Claus, Sylvia Purrins, and Perry T. Rathbone in Greek line dance, Christmas party, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1960s.

But by the mid-1960s there was a seismic change rumbling beneath the surface. The pressure rose like the mercury in a thermometer – the demands of the centennial compounded by the need for new kinds and sources of money. The Museum’s operations had reached a tipping point in their size and scale. While Rathbone instinctively understood how to raise revenue by enlarging the membership and increasing the programs of the Museum, he had never considered direct fund-raising a part of his job. This was not what he had been trained to do. Furthermore, it was no part of the thinking of the genteel board of trustees. As the gentlemen they were, they prided themselves on the occasional burst of generosity for the sake of a special project or acquisition or the covering of a small debt. But the idea of making a major donation to a general fund drive was outside their habit of mind or range of vision.

At the start of the centennial drive Rathbone started looking around for a professional fund-raiser, at the time a fairly new concept. After interviewing a few candidates, he hired a firm by the name of Ketchum, a name, he mused, that suited a fund-raiser. But Rathbone quickly saw that the Ketchum firm, or anyone else outside the museum family, would not be an answer to all the challenges. A professional fund-raiser can lay out a timetable and keep track of progress. Essentially, he surmised, “you pay someone to force you to do the job you have to do.”24

What Rathbone also needed was leadership from inside the museum family – namely, a trustee to chair the campaign. His notion of the perfect fit was John “Jack” Gardner, whose family had served cultural institutions in Boston for generations, whose great-aunt Isabella Stewart Gardner, a native New Yorker, stunned Boston society with her extraordinary collection of European art and the creation of Fenway Court. Young Jack had followed his father George Peabody “Peabo” Gardner onto the board, representing the fourth generation in his family serving as stewards of the great Museum. Jack Gardner was “the right kind of proper Bostonian,”25 Rathbone believed, to assume the role of figurehead for the campaign. Furthermore, he had recently been elected treasurer to the trustees in 1960, replacing one of Rathbone’s closest confidantes, Robert Baldwin, a broker at State Street Bank, who had served for many years “untangling administrative knots and making himself useful to everyone.”26 But Rathbone had no success persuading Gardner, or any other member of the board, to take on this important role, for the Museum had never had to reach outside its own little family for anything before, and it seemed impossible to change the habits of even the younger members of the old guard. The last thing any of them wanted to do was to go around the town with a tin cup.

Besides, these same board members were all busy supporting a full range of other beloved nonprofits. Boston had more than its share, and each commanded a loyal following. There was Harvard and MIT, the Boston Symphony Orchestra, and the brand-new Museum of Science, headed by the aggressive Bradford Washburn. There were hospitals and schools. “Owing to the great number of nonprofit institutions,” lamented Rathbone, “the competition is keener [in Boston] per capita than anywhere else in the country.”27 While competition outside the walls of the MFA was rife, the spirit inside was tepid. Not since its inception had there been any kind of fund-raising effort, and among the general population, as well as the inner circles, “there was no habit of giving to the MFA.”28