Читать книгу The Boston Raphael - Belinda Rathbone - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1965

IN 1965 the Boston Museum of Fine Arts was enjoying a revival that was long overdue. During the previous decade attendance figures had tripled; membership had multiplied six times; publications had grown from a trickle of drab little booklets into a steady flow of tempting full-color catalogs, calendars, and postcards; and fifty exhibition galleries had been completely renovated, their treasures brought to life in the glow of new lighting and fresh installations. Collaborating with the local educational station WGBH, the MFA was the first museum in America to be wired for television, hosting on-site programs for both adults and children several times a week, and thereby expanding its public outreach exponentially. Not least, the collections had grown by hundreds of artworks, bringing new strength to every department, including the promise earlier that year of the entire collection of eighteenth-century French art belonging to the late Forsyth Wickes. On the evening of December 10, 1965, the Museum’s volunteer Ladies Committee staged a surprise tenth anniversary party for the man who was responsible for instigating these dramatic developments: director Perry T. Rathbone.

In an elaborate ruse in which his wife, Rettles, was a key conspirator, Rathbone arrived in his black tie and dinner jacket at the Huntington Avenue entrance, where he was greeted by a throng of two hundred friends. Amid a chorus of congratulations he was led up the grand staircase – red-carpeted for the occasion – to shake hands with beaming well-wishers every step of the way. He was genuinely flabbergasted. “I, the unsuspecting victim,” he wrote in his journal that week, “was led to the ‘slaughter’ by Rettles, who turned out to be the most subtle actress of them all in this colossal conspiracy.”1 Rettles, shy and demure, was every bit the woman behind her man, following him up the stairs, smiling and embracing the guests, radiant in her newest Bonwit Teller evening dress.

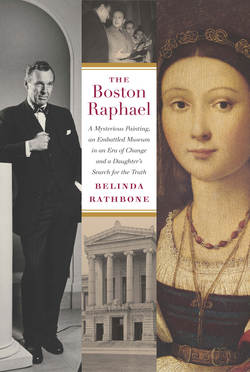

Perry and Rettles Rathbone greeting guests at party honoring PTR’s 10th anniversary as director, December 1965.

At the top of the stairs Ralph Lowell, the MFA’s president of the board, crowned Rathbone with a laurel wreath. There followed general cocktail hubbub in the rotunda and then a dinner dance in the spacious Tapestry Hall just beyond. It was well known that the director had lately been taken by an insatiable love affair with Greece – both modern and ancient – and the theme was custom-made to his taste: a Greek menu of lamb, steeped in the Mediterranean flavors of lemon and garlic, washed down with the pinesap-flavored white wine retsina, and the cloudy, licorice-flavored aperitif ouzo, while a lively Greek band serenaded them all. Unprepared as he was to be the object of celebration that evening, Rathbone mustered his best modern Greek to express his thanks and amazement, which amused everyone, including the Greek musicians. Later, with typical spontaneity and joie de vivre, he led anyone willing in a Greek line dance. “The evening had a genius hard to define,” he fondly recalled, attributing it most of all to “the spirit, personality, the imagination of Frannie Hallowell.”2

Frances Weeks Hallowell was the first woman to join the MFA board of trustees. From the start, Frannie and Perry were natural allies. At a welcoming dinner for the new director ten years earlier, they were seated next to each other, and Perry could see immediately that this bright, attractive, and socially connected woman could be a major asset to the cause, and not just as a trustee. To that old boy network she brought her feminine talent for social entertaining as well as the tactical mind of a politician. In another age she might well have been running for public office. Her father, Sinclair Weeks, was onetime Republican senator for Massachusetts and secretary of commerce under President Eisenhower in the 1950s. As his eldest child, Frannie learned firsthand from his example and inherited his political acumen, as well as his ambition. It came naturally to her to be a step ahead of the game, and her mind teemed with ideas. Over dinner on the evening when they first met, Perry asked Frannie if she would be willing to organize a group of women volunteers for the MFA. “Will I?” she replied with a big smile. “I can’t wait!”3 Unbeknownst to Perry, Frannie had conjured up the notion of a women’s committee of volunteers almost as soon as she was elected to the board just a few months before. With Rathbone in charge, her idea took flight.

The tenth anniversary party was typical of Hallowell’s genius, and Rathbone was right in awarding her the lion’s share of credit in the creation of that magical evening. But perhaps what was harder for him to define – the real magic – was the spirit of festivity and celebration that he himself had inspired. By now his skeptics had taken a backseat, and the old guard had laid down their arms. He was loved by his staff, and also by his public. His energy and optimism had pervaded every corner of the Museum. He had galvanized his team to the cause, and the cause was never far from his thoughts.

Rathbone understood, as well as anyone, that the party served more purposes than to flatter and entertain the MFA’s inner circle. Nothing works like marking an occasion to remind people of their good fortune, and also their debt. The major donors were there, and Rathbone was especially pleased to see Alvan Fuller, the heir to his family’s collection of old master paintings, who had come in specially for the occasion from his winter home in Palm Beach. In the midst of the noisy celebration Fuller took Rathbone aside to mention his promise of a gift to the Museum of a late Rembrandt. “No doubt the spirit of the moment inspired the resolution,” observed Rathbone. “One cannot underestimate the importance of such events.”4

Perry T. Rathbone, Frannie Hallowell, and Ralph Lowell cutting cake at the tenth anniversary of Ladies Committee, 1966.

While there was much to be proud of, Rathbone was in no position to rest on his crown of laurels. For with the tangible achievements of the past ten years behind him, he now faced his most challenging years as a museum director. For those were challenging times in every way. Looming in the background of the Museum’s cultural renaissance in the 1960s was the moody aftermath of the assassination of President Kennedy and the sudden escalation of the Vietnam War. For America, 1965 had been one hell of a year. On February 6 President Johnson ordered the bombing of a North Vietnamese army camp near Dong Hoi in retaliation for their attack on a US military outpost. In March he increased the pressure with continuous air assaults and soon afterward sent in the first round of American troops while the Vietcong tenaciously stood their ground. On February 21 Malcolm X was assassinated in the midst of his speech at the Audubon Ballroom in New York City. In March Martin Luther King Jr. led a civil rights march in Alabama from Selma to Montgomery. In August President Johnson secured the passage of the Voting Rights Act, giving all African Americans the right to vote. But just five days later, race riots erupted in the black ghetto of Watts in Los Angeles. A confrontation between a black resident and a white policeman escalated into a five-day urban nightmare. More than thirty people died in the melee, and more than two hundred buildings were completely destroyed by fire. From the point of view of many African Americans, among others, the Voting Rights Act was too little, too late.

They were not the only segment of the population that was dissatisfied. A generation of baby boomers was coming of age, and they were not necessarily inclined to model themselves on their parents’ example. Suspicious of their central government, disenchanted with the American class system, and sympathetic to the underdogs of society, they railed against materialism, hypocrisy, and the apparent complacency of the older generation. “I can’t get no satisfaction,” ranted Mick Jagger to the angry twang of electric guitars. The song was a number one hit in 1965, its rage touching a hot spot in the American psyche and charging the airwaves with a menacing undercurrent. Everyone had something to complain about, and everyone had the right to be heard. It was all part of a rapidly changing social landscape.

One of the greatest personal thrills of Rathbone’s directorship had been to forge the MFA’s connection with the Kennedy White House. The Kennedy years made Boston a star on the political and cultural map, and its former senator elected president put Massachusetts in the spotlight. With Boston as his hometown and Harvard as his alma mater, John F. Kennedy drew from the Harvard faculty many of his closest advisors, including Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., John Kenneth Galbraith, and McGeorge Bundy. At the inauguration ceremonies Boston’s own Cardinal Cushing gave the invocation for the first Irish Catholic president in US history. Many notables of Boston’s political and cultural scene were invited to the inaugural celebrations, including Mr. and Mrs. Perry T. Rathbone.5

For the first time in Rathbone’s working life, there was a First Lady in the White House with a genuine interest and background in the arts. Rathbone immediately grasped how powerful a message this could be for every museum in the land, and for Boston in particular. “It means a great deal in our country, where art hasn’t had the sort of inborn respect it has had for generations in Europe,” he told the Christian Science Monitor of Jacqueline Kennedy’s impact on the arts, “to have someone take it so seriously and recognize its importance. I think it will be a great boon to American culture in general.”6 He seized the moment to make the connection right away, for all too often Boston stood in the shadow of New York and Washington. When he learned that Mrs. Kennedy was redecorating the White House, searching for appropriate pieces of American furniture, decorative arts, and paintings, Rathbone made it known through John Walker, director of the National Gallery, in Washington, that the MFA would gladly lend works of art to the cause. With her famous soft-spoken charm, the First Lady responded enthusiastically, and Rathbone had the distinct pleasure of selecting two dozen works of art from the MFA for her to choose from.

Perry T. Rathbone and Jacqueline Kennedy, the White House, April 1961.

She chose eleven – for the State Dining Room, George Healy’s portrait of Daniel Webster (to be hung directly across from the full-length portrait of Abraham Lincoln by the same artist), and for the family’s private quarters, watercolors by American masters with special ties to Boston: Winslow Homer, Edward Hopper, Maurice Prendergast, and John Singer Sargent, “helping to add a New England flavor”7 to their domestic scene. The story made for a glamorous piece of publicity – to make known the genuine interest of the White House in what Boston had to offer – and Rathbone took full advantage of it.

Besides restoring the White House to its former glory, a top priority on the First Lady’s agenda was to personally embrace and celebrate America’s cultural leaders. In November 1961 she invited the Spanish expatriate cellist Pablo Casals to perform for a private evening at the White House. For the first time since he had left Fascist Spain for Puerto Rico, Casals consented to play for an audience. For this special event the Kennedys invited the cream of American cultural society, including the MFA’s director and his wife, for a black-tie dinner before the concert. Hardly a detail of this legendary evening was lost on Rathbone. He noted the flowers, the dinner service, the choice of wine, the fish mousse and the filet de bœuf, the First Lady’s evening dress (“a green chartreuse column of silk”), and the decoration of every room they passed through. When Pablo Casals performed after dinner in the East Room, he savored every note: “a glittering company all around absorbing great sonorous music from a great artist, I was conscious of my privilege every moment.”8

A few months later, the French minister of culture, André Malraux, sent the Mona Lisa to Washington to honor the Kennedys’ embrace of the arts in America. The most famous picture in the world hung in the National Gallery for three weeks, attracting some five hundred thousand visitors before traveling to the Metropolitan Museum, in New York, where an estimated one million lined up to pay homage. With typical can-do spirit, Rathbone asked the French Ministry if they could extend the loan to the MFA, not only because it was one of the three most important museums in America but also because Boston, with its vast college student population, was in many ways, he asserted, “the intellectual capital of the United States.”9 The Mona Lisa did not travel to Boston, but it was typical of Rathbone’s tireless efforts to draw national attention to his institution.

But with the abrupt end to the Kennedy years, Washington’s spirit of support for the arts withered. That bright shining moment was but a brief promise and in retrospect shone all the brighter for it. The country entered a period of mourning, not only for the president but also for its shattered identity. At the same time, there perhaps was never a time to equal the 1960s in its ravenous appetite for change. Every kind of belief or value system was up for review; nothing was standing on solid ground. While this was a time of idealism and liberalism, when a postwar prosperity was supposed to be within everyone’s grasp, it was also a time of accelerated forward movement without a clear sense of consequences or of what might be lost in the transition to a new age.

Commercial movies such as Bonnie and Clyde, The Pawnbroker, and Blow-Up were reaching unprecedented levels of explicit sex and violence, bursting through the boundaries of acceptability like a runaway car chase. At the same time, horrendous images of the war in Vietnam came home to everyone with a TV set, increasingly in “living color” – which only added to the confusion of what was right and what was real, which black-and-white film had somehow made clearer – stirring up even more anger at the administration and confusion about America’s role in Southeast Asia. In the face of LBJ’s vision of The Great Society, and with the success of his considerable legislation to further that end, frustration and anger were nevertheless widespread, unmitigated by a new and seemingly un quenchable sense of entitlement. Violent crime was on the rise, a fact that many attributed to racial tension and the conditions of poverty in the cities. In Boston, the 1960s was a decade of enormous growth in terms of its black population, which nearly doubled, while many of the Jewish communities left Roxbury and Jamaica Plain for the wealthier neighborhoods of Newton and Brookline, and the working-class Irish of Charlestown and South Boston now competed with African Americans for jobs and resources in the decreasing domain for small industry. Ethnic neighborhoods drew their battle lines and lived in precarious hostility.

The city Rathbone served as a museum director was giving way to upheavals of every kind. With the rise in violent crime, he feared for the Museum’s safety, given its proximity to the poor neighborhoods of Roxbury. City politicians struggled with a growing population of the needy, while the well-to-do fled to the suburbs. New interest groups – blacks, women, local artists – began to make themselves felt in the cultural scene and were not shy about making their demands widely known.

There were changes in the physical landscape as well. An ongoing building boom surged recklessly over town and country, devastating old neighborhoods and historic monuments. The 1960s was a time of rampant new building projects, thanks to a zealous and often misguided group of second-generation modernist architects, and also the destruction of sacred monuments of American culture, many an architectural treasure, old neighborhood, and park landscape. In 1960 the historic West End of Boston was demolished, the old neighborhood replaced by anonymous high-rise apartment buildings with billboard signs advertising “If you lived here, you’d be home now” to the drivers of gas-guzzling American cars stuck in rush hour traffic on their way home to the northern suburbs. It took charismatic cultural leaders to stem the tide where they could. Jackie Kennedy’s preservationist mission and high standards of taste left their indelible impression. Lady Bird Johnson followed with a campaign to limit the spread of billboard advertising that was spoiling the view from the highways. In the same way that these women served a key role in Washington in the way of enlightened restoration programs, Rathbone took on the struggle in Boston.

America’s increasing dependence on the automobile had made the development of the interstate highway system under Eisenhower a priority since the 1950s. In the early 1960s the plan for the construction of the so-called Inner Belt in Boston threatened to cut an eight-lane superhighway through working-class neighborhoods of Cambridge, Somerville, and Jamaica Plain and through the heart of Boston, including the parkland along the Fens just across from the Museum. City politicians perceived the Inner Belt as a way of bringing life and commerce to their dying inner city, but underestimated the devastating effect it would have on the city itself as a livable option. As the Inner Belt plans were gradually revealed to the public, a storm of angry protests from local residents followed. By 1965 these had reached their peak. As director of the MFA, Rathbone was a key spokesman for the opposition, addressing business and civic leaders at meetings, and leading the loudest and angriest interest groups at the public hearings in Boston. The highway’s presence would isolate the Museum, he argued, and sever its connection with the city’s thousands of university students. One proposed route would take over the Museum’s parking lot, another its museum school. First its construction, and later its constant activity, might also endanger the Museum’s collections. A study group, including seismologists, worked for months on the possible effects of the highway on the Museum’s structure and contents. Most of all, stated Rathbone at one such hearing, it would ruin the fabric of the city and everything that was unique about Boston, turning it “into a precinct of no more distinction than downtown Tulsa or Wichita.” The whole idea, he argued, was an unmitigated disaster, a product of “bulldozer psychology.”10 After a ten-year struggle lasting through the 1960s, the opposition won their case in one of the first successful grassroots preservation campaigns in America, but not without a titanic effort.

In a similar spirit of misguided urban improvement favoring the car, the city of Cambridge made plans to widen Memorial Drive along the Charles River, which would mean destroying the stately avenue of sycamore trees that had been there as long as anyone could remember. Civic-minded Cantabrigians raised an organized protest, with Isabella Halsted, secretary of the MFA Ladies Committee and a resident of Memorial Drive, among its most ardent participants. Known as “the Battle of the Sycamores,” it waged on until the plan was defeated and the sycamores left standing. This was an early and therefore significant victory in the ongoing battle between city residents and politicians for the highway, and it bolstered the Inner Belt opposition.

As much as these issues were an unwanted distraction from his day job, Rathbone was a cultural figurehead in Boston, if not in all of New England, and there was no getting out of it. His journal of the mid-1960s is rife with complaints about the calls on his time and the distractions from the Museum. It dampened his spirits and drained his energy, but he rose to the challenge, for it was in his nature to be wary of any enterprise that threatened to destroy the heart of an old city. Truth and Beauty were on trial, and it was up to a museum director to set them right. “Inner Belt, BRA,11 Fund-raising problems give me sleepless nights,”12 Rathbone admitted in his journal on October 19, 1965.

Rathbone was especially sensitive to what was going up and what was coming down, in Cambridge and Boston. As much as he was devoted to Harvard, his alma mater, by the 1960s he deplored how the university was changing the physical fabric of Cambridge, which was now his permanent home. In 1965, at the first sight of the completed Peabody Terrace, a new residence for married students at Harvard, he was dismayed at the way these buildings permanently marred the river view of his beloved undergraduate years. Much of the responsibility for this lay with Josep Lluís Sert, the Catalan architect who was the dean of Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. Rathbone liked the Serts personally – Josep and his wife, Mancha, were small and slight, urbane and intelligent – and particularly enjoyed the modern European element they brought to Cambridge. He also admired Sert’s architecture – in theory – but context had everything to do with it. He strenuously objected to Sert’s guiding principle that “Cambridge must rise!” As he mused somewhat bitterly, “the smaller the man the bigger his ambition to impose himself.”13

Sert’s Holyoke Center now towered ten stories over Harvard Square. And with the erection two years earlier of the first and only Le Corbusier building in America, the Carpenter Center (also thanks to Sert’s strenuous advocacy), Rathbone was outraged. He especially resented that the Carpenter Center, which eventually became the home of Harvard’s studio arts, had taken up the only available space on Quincy Street long designated for the Fogg Museum’s inevitable expansion. The new building destroyed the unity of Quincy Street, “having no relationship whatsoever to its surroundings. Nor has this tortured pile of concrete designed by Corbusier have any apparent logic within or without.”14

While he bemoaned the erection of new buildings around the Harvard campus, Rathbone also witnessed the University’s neglect or misuse of hallowed historic houses, especially Elmwood, the federal mansion at the far west end of Cambridge that is now the official residence of the University’s president. In the 1960s the Harvard Corporation seriously considered the idea of tearing the house down rather than admitting to the need and expense of restoring and maintaining it. In the midst of this debate, the dean of faculty, Franklin Ford, lived at Elmwood in its somewhat neglected state of repair. After going for drinks one evening with the dean and his wife, Rathbone was shocked at the state of its interior. “The heart of Elmwood has been carved out and thrown away,” he mourned. “Elmwood, home of Lt. Gov. Oliver, of Eldridge Gerry, of James Russell Lowell, of Kingsley Porter,15 has been ‘suburbanized,’ brought to a level of mediocrity that is scarcely believable . . . as Elmwood stands today it is a sort of ‘Harvard ruin.’ It exists but I cannot say it is alive.”16

Not quite yet a ruin was Memorial Hall, the grand old Victorian Gothic memorial to Harvard’s own Civil War Union dead. The imposing cathedral-shaped building had lost the top of its clock tower in a 1954 fire. Its soaring spire had been reduced to a squared-off stump, and ten years later Harvard showed no signs of interest in restoring it. Across the river the prosaic Prudential Tower rose fifty-two stories out of its element, the first skyscraper to challenge the coherent skyline of Boston’s Victorian Back Bay. Soon the little streets of downtown Boston would give way to a host of tall office buildings towering over the historic old State House and the Old South Meeting House. And so the mania for modernism and change raged through the decade, inexorably changing the face of old Boston.

In his youth Rathbone had championed modernism, but by the mid-1960s he no longer necessarily embraced the latest contemporary art. While he admired the abstract expressionists with some reservation, he now looked downright warily upon the emerging pop artists who were overtaking them – Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, and especially Andy Warhol. He dutifully kept abreast of the art magazines of the day, such as Art in America and Artforum, but felt impatience with the obfuscation of art critics. He resented an approach that seemed to relegate connoisseurship to a lower position on the scale. Was theory overtaking the direct appreciation of the physical object? Was the new intellectualism doing its best to mystify rather than clarify? Was the new art drowning out the sacred values of beauty, craft, and technical innovation? Perhaps most of all, he saw his role as a champion of modern art being usurped and no longer urgent. The world had caught up with him – in fact, it was streaking past – and that particular adventure was no longer quite fresh.

Rathbone continued to be his socially adventurous self, eager for new experiences and new contacts, excited by the liberalism of the younger generation. The sexual revolution found him perhaps somewhat regretful that he had not been a youth in such a frankly liberated age while at the same time concerned for his teenage daughters’ virtue. Harvard still required a coat and tie in the dining halls, but soon these rules would give way to the pressures of antibourgeois proletarianism. Now it seemed that educated young men dressed like workmen in jeans and T-shirts, young women exposed more skin with every passing year, and instead of dancing to the steps of the fox-trot or the waltz, young people improvised and gyrated to the beat and twang of ear-splitting electric guitars. Yet while he bemoaned the demise of ballroom dancing, he leapt into the fray with a room full of the younger generation doing the Mashed Potato and the Twist, ever ready to experiment, to taste and engage in the curiosities of his time.

Alert to every nuance of a shifting culture, Rathbone was equivocal about the waning of the class system, which to him simply meant a lessening of certain standards. Without such standards, what would become of the beautiful traditions of his youth? Along with the class system seemed to go table manners, dress codes, and the English language. Returning from a big coming-out party in the mid-1960s, he lamented, “Somehow these debutante parties lack the glamour, the beauty, the ‘occasion’ that they certainly possessed when I was a youth. I suppose the basic reason is that their social meaning is dwindling.”17 It was not only the class system that was weakening but also the subordinate role of women in society. A revolution was brewing, its first signs in how a young woman of the next generation dressed. She wore a bikini on the beach and not much more on the street. Hemlines were on the rise; so were tight leather boots up to the knee and hot pants. Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, published in 1963, sparked the beginning of the women’s movement and coincided with the introduction and growing popularity of the oral contraceptive, which opened the way to women’s sexual freedom. And who would have believed that to the next generation “coming out” in society would mean declaring yourself a homosexual rather than the carefully programmed activities of the debutante, the well-bred girl whose well-off parents were officially announcing her eligibility to be married? Was it imaginable that the word “elite” was on its way from being a word of status to something to be reviled, and soon to become a degrading -ism?

At the time Rathbone’s personality split along the lines of his dual instincts – equally strong – between his conservative and adventurous selves, between his love of tradition and his need for the vibrancy of the new and the experimental. His mind was still open, but the issues had changed color. He was at midlife, a point when many a modernist favoring change meets the inner preservationist. The older generation was dying off, passing on the mantle of responsibility and tradition. Now his mind reached as far backward in his memory as it did forward into the unknown. His mother died in 1960, and the death of Rettles’s aunt, Mary Peckitt, a grand dame of Washington, D.C., came soon afterward. She left a welcome trust fund, a house packed to the rafters with Renaissance Revival furniture, and an empty space in the family topography that signaled the end of an era.

Now in his midfifties, Rathbone had three children who were in their awkward teens. Peter, the eldest, not appearing to be ready for college after graduating from Brooks School, had enlisted in the army, signing on for an additional year with an assignment in Europe18 in a tactical move to avoid being drafted and sent to Vietnam. Peter, once pictured in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch at age six as the “youngest collector” with his little Calder stabile of a giraffe, groomed from an early age to appreciate the finer things in life, was home for the holidays from basic training in Fort Dix with his head shaven, soon to be stationed in Germany for three years, an army private with a safe but soul-crushing office job.

They say that siblings are like leaves on a branch, with each leaf turning the opposite direction from the last to better catch the light. Eliza had laid claim to the front seat of our father’s tutelage. She would be graduating from the ultratraditional Miss Porter’s School in Farmington, Connecticut, with a class that might with some accuracy be called the last of the debutantes. As his third child and second daughter, I escaped a certain degree of scrutiny and grooming for the role my sister inherited. It seemed less effort was made to direct me, or was it that I was less inclined to take direction, or both? A year later I would attend an educational experiment called Simon’s Rock in the Berkshires as a member of its first graduating class. My sister and I were only two years apart, but the changes taking place in those years meant that we almost belonged to different generations. She had a coming-out party; two years later I could see no point in doing the same.

The magic years were over. No one believed in Santa Claus anymore. Life had marched on at its steady pace, and then suddenly, it seemed to have gone by in a flash. “This was perhaps our last Christmas with all three children,” my father noted in his diary in 1965, although as a parent of three teenagers, he was also gratified to have maintained their respect and affection in the era of the so-called generation gap. “That they like us and our company and that of our friends means everything.”19

The years of his generation’s ascendancy had peaked. From now on it would be a struggle to stay one step ahead of the trends. And still, there was so much work to do. His former battle cry, “Art is for everyone,” was no longer new. What had become of the young man famous for ushering in change? For the first time in his life Rathbone felt that he might be behind the curve instead of in his customary place: ahead of it.

Having kept a journal faithfully since the early 1950s, in 1966 his writing trailed off, with hardly an entry between January and September. Confronting the blank pages on September 30, 1966, he wrote, “Months of neglect stare me in the face. The ever increasing pressure of life puts writing a journal almost beyond endurance.”20