Читать книгу The Boston Raphael - Belinda Rathbone - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe Changing Face of the Board

IN THE 1960S Rathbone actively sought to change the complexion of the Museum’s aging board of trustees, to bring in younger members “whose minds were open, and who already had different ideas of what a museum might be.”1 Among the young trustees of an old Boston tribe was Lewis Cabot, who joined the board in 1966. A keen collector of modern art as well as a recent graduate of Harvard Business School, Cabot, who was a youthful twenty-eight at the time of his election to the board, later somewhat facetiously commented that his election was part of an effort “to bring the average age down from senility.”2 In seeking out younger individuals of wealth with a passion for art, Rathbone knew better than to confine himself to old Boston society. He introduced Landon Clay, a collector of pre-Columbian art from Savannah; John Goelet, a collector of Asian and Islamic art from New York; and Jeptha Wade, whose grandfather was a well-known collector in Cleveland. Also noteworthy were the growing number of women on the board, with Helen Bernat, a collector of Asiatic art and also one of the first Jewish members, joining in 1966, and contemporary art collector Susan Morse Hilles in 1968, not to mention the steady representation of the Ladies Committee by its standing chairwoman. Thus new blood began to trickle in – an emerging generation of trustees with a different kind of attitude.

Rathbone also managed to persuade the trustees to make a landmark decision he had been promoting for some time. This was to open up their efforts to raise money to the business sector and to institute corporate memberships. “No individuals such as those who built this place are going to pull us out of the fiscal problem we have,”3 Rathbone told an interviewer in 1967. A promising alternative, which was gaining some credibility at that time, was for the corporate wealth of the country to “step into the breach.”4,5 While before it was considered inappropriate for a cultural institution to accept money from a business (and plenty of corporate executives felt the same way), the time had come to actively engage Boston’s business community, to reach out to “more entrepreneurial people who had larger sums of money to play with,” said Lewis Cabot, “and who were – dare I say it – anxious to make a social position of their lives.”6 Rathbone would be the first to admit that pure devotion to art was not the only motive of the corporate sponsor, that to have one’s name attached to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts was “a passport to higher things or better circles. It’s quite a feather in one’s cap.”7 While this remained an embarrassment to some members of the board, the resolution passed.

Rettles and Perry Rathbone, Charlotte and Ralph Lowell, receiving line, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1960s.

Among the first corporate members to respond to this initiative was the local canned-food enterprise, the William Underwood Company, with a gift of $500 in 1965, which in the context of the times seemed promising. Underwood was doing very well with its signature product Underwood Deviled Ham and had accelerated into takeover mode, expanding its base that year with the acquisition of Burnham & Morrill of Portland, Maine, best known for its B&M baked beans (and incidentally a traditional, if somewhat disparaged, staple of the Boston diet). Underwood’s CEO, a tall, imposing man named George Seybolt, was acquainted with MFA trustee William Appleton Coolidge, who had solicited his help in raising money for the Episcopal diocese. Coolidge made the introductions while Seybolt did the heavy lifting, and they managed to reach their goal of $5 million. Bill Coolidge (not to be confused with his distant cousin, John Coolidge, of the Fogg), a one time senior partner with the Boston law firm Ropes & Gray and a venture capitalist, was generally considered the richest man on the board, and in his quiet, patrician way, he was a force. “When Bill Coolidge had something to say,” recalled trustee Jack Gardner, “everybody listened.”8 At the start of the centennial fund drive in 1965, Bill Coolidge recommended Seybolt as the kind of business mind they needed to enlist and consult. An aggressive fund-raiser with a high profile in the Chamber of Commerce and a lively interest in American antiques, Seybolt, as Rathbone later summarized, “seemed to be the man.”9

Even though Seybolt was an altogether different kind of person from any other member of the genteel museum community – a high school graduate of the Valley Forge Military Academy among the overwhelmingly Harvard-educated board – once he began offering his services pro bono, it was but a short step to his becoming a trustee. Rathbone vividly recalled the meeting to which Seybolt was invited as a special guest to offer his advice on fund-raising tactics ahead. Seybolt looked around the table, meeting the eyes of everyone assembled, and said meaningfully, “This is a job for a trustee, isn’t it?”10 And in short order, he was elected in February 1966.

At first Rathbone was relieved to have Seybolt on the board to help him focus the trustees’ attention on the Museum’s financial needs and shoulder the burden of fund-raising. If more established members of the board were unwilling to lead the charge, what could he do? If Seybolt wasn’t exactly the image of old Boston, he was the image, perhaps, of the new Boston. Rathbone had understood from the moment he arrived there that the mold had to be broken, and here it was breaking in a new way. Seybolt was ready and willing. More than that, he was aggressive, he was ambitious, and it was clear that he had his eye on the bottom line, and that was what mattered now.

Seybolt immediately perceived flaws in the system. For one thing, the board meetings were too short, and too few – President Ralph Lowell saw no reasonable call for more than three or four meetings a year and took pride in the fact that they usually concluded within two hours. For another, the board did not seem to be presented with any real problems to solve. Lowell would review the director’s report about an hour before the meeting, and then they would all sit down around the table to listen and discuss it. “Everything at that point was very polite, deferential,” remembered Cabot, “a steward without being a visionary was the way the trustee saw his role.”11 These were the quiet, responsible guardians of a public trust, stewards of a great ship, but they were not her captain. When faced with a proposal of any kind, Ralph Lowell “just smiled and signed, smiled and signed.”12

“What they got was canned food,” Seybolt complained with an interesting choice of metaphor, “all prepared, even chewed and regurgitated – they got this pat stuff.” As he observed the proceedings at one meeting after another, Seybolt quickly concluded that he himself was “the only one there that was really living in the world as it was.”13

Around the Museum, staff and trustees alike noticed that Seybolt’s ideas were strikingly corporate, his manners were alternately intimidating and overfamiliar, and it was clear he had an agenda. Some perceived his ambition was not just for the MFA but also for himself – to gain access to the top tier of Boston society. Lewis Cabot regarded him as “a very complicated man, driven by social prestige, wanting to be acknowledged as one of the substantial people in what was then called ‘the Vault’14 downtown.”15 It was rumored that Seybolt’s election to the board was contingent on his membership to the exclusive Somerset Club on Beacon Hill. With his wife, Hortense, he began to appear at high-profile museum events, where the columnists from the Boston Globe and the Boston Herald would spotlight the up-and-coming and where the old money would rub shoulders with the new. His tall, heavy figure, dressed in a white dinner jacket and a dress shirt embellished by an extravagant ruffle, betrayed that Seybolt’s origins were far from Back Bay Boston.

At the start of the capital campaign Seybolt accompanied Rathbone to New York to meet with all the heads of the big foundations, the first time ever that the Museum had approached them for funding. Seybolt had already observed that Rathbone was “a master salesman.”16 He had watched him raise money for the acquisition of a medieval sculpture – the bewitching Virgin and Child on a Crescent Moon – in the midst of a dinner party, with not one person at the table suspecting they were being “set up.” In New York, as Rathbone recalled, they did their Mutt and Jeff act, with Rathbone talking up one aspect of the Museum, and Seybolt another. They made an odd pair – Rathbone, charming and ebullient, a person whose instinct was to make each encounter social and personal, easily conveying his knowledge and passion for art and for the Museum, alongside Seybolt, with his intimidating eagle eye and razor-sharp business sense to remind everyone exactly what they were really there for. With their assault on the big foundations, Rathbone and Seybolt garnered the first round of centennial donations.

In 1968, as the centennial drew near, they had raised about $8 million, but their goal of $20 million was still far from achieved. Ralph Lowell retired as president of the board that year. Seybolt, who had vowed as a young boy that he would be president of something by the time he was forty,17 had surpassed his goal by his midfifties and was ready to be president of something else. Furthermore, he had proven to his fellow trustees that he had the administrative skills they either lacked or did not choose to apply to the MFA, and to some trustees he seemed to be the obvious candidate to succeed Lowell as president of the board.

As the new president, Seybolt immediately laid out his agenda. The Great Inflation was up and running, and museums across the country were experiencing financial strain as never before. Seybolt’s approach was first of all to confront “the practical hard realities of the world”18 that his fellow board members had ignored. The MFA’s annual report of that year presented a dire picture. “1968 was a year of physical expansion, administrative enlargement, and financial retrenchment,”19 as Rathbone broadly stated the facts that year. Treasurer Jack Gardner admitted a deficit that had grown alarmingly “due to the net increase in exhibition expense”20 and announced that a major overhaul of the budget was under way.

Suddenly, everything had to be accounted for – every dollar, every minute of the day. “All of a sudden everyone woke up,” recalled Lewis Cabot. “How much did it cost to change a lightbulb? There were new ways to size up the total value of the museum as compared to the total cost of maintaining it, in ways taught at the Harvard Business School – the museum itself as one big cost operation.”21 In 1967, they estimated, it cost about $15,000 a day to keep the doors of the Museum open.

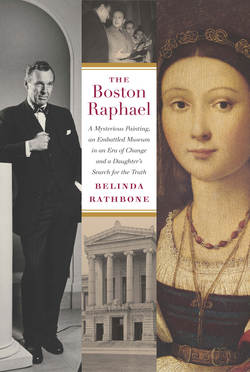

Perry Townsend Rathbone, Director, and George Seybolt, President, Board of Trustees, 1967–1971.

Seybolt’s appointment as president in 1968 also coincided with the Museum’s decision to charge admission for the first time in decades. It was an action Rathbone was reluctant to take, but in the face of the Museum’s financial straits, it was unavoidable – the kind of hard-nosed business decision that required a real businessman to make. As a result, attendance figures dropped for the first time since Rathbone had been director; until then they had been steadily on the rise. The downside of the admission charge, however, was somewhat mitigated by a related initiative that helped maintain the Museum’s democratic goals and commitment to the community: an appeal for public funds to admit children younger than age sixteen free of charge. Rathbone made the Museum’s case to the General Court, inviting city leaders and legislators to the Museum for luncheons and special tours, and aided by strong editorial support from the local press, the MFA received public money from the city of Boston for the first time in its history.

Also that year, Rathbone hired the Museum’s first in-house head of development, the amiable James Griswold, formerly treasurer of Phillips Exeter Academy.22 At the time the very idea of a development department was a new concept for art museums, and its exact position within the hierarchy of the administration not fully defined. It was soon evident to Griswold that “they didn’t know what to do with me.” Not only were the boundaries of his position unclear, but the chain of command was too – he didn’t know whether he was working for the director, as he had been led to believe, or the president of the board. As Griswold recalled, Seybolt had “a totally different concept of what a trustee’s job was. He wanted to be the boss and he ran it with a horse-whip.”23

Seybolt had a vision and a plan, and he took on the presidency in a strikingly proactive spirit. It appeared that for him the MFA was becoming a nearly full-time occupation. He suggested to Rathbone that he needed “a place to hang his hat,”24 then requested his own telephone, and soon he wanted a desk to put it on. It would not be long before he commanded his own office suite, which meant the regrettable closing of the primitive art gallery25 in the ongoing encroachment of offices on gallery space, and two private secretaries.

Seybolt also perceived problems in the structure of the board going forward. “To make big changes in the system wasn’t possible,” he said, “unless you brought in new votes, so to speak.” Even with the addition of new, younger members, there was still a majority of old-timers, “who tended to be drenched and instilled and distilled with their ancestors,”26 as Seybolt described them. Furthermore, the structure of the board as originally laid out in the bylaws was top-heavy with ex officio members, including not only the token representatives of the city government, such as the mayor and the superintendent of schools, but also three each from the Museum’s founding institutions: Harvard, MIT, and the Boston Athenæum. “The cradle of the Museum of Fine Arts was so surrounded by fairy godmothers,” wrote Nathaniel Burt of its early years, “that it almost suffocated.”27 Rathbone, who as director was also automatically a trustee with a voice and a vote,28 agreed with Seybolt. For while this arrangement represented a balance between professional input and financial support, it also meant that the ex officio members had other priorities. Said Rathbone, there was “a need for new blood and people who were devoted to the Museum first, last, and most importantly, and not to others.”29 In due course Rathbone and Seybolt persuaded the rest of the trustees to agree to change the bylaws to cut back on the ex officio members from nine to three – one from each of the founding institutions – and thus expand the limit of elective trustees by six.

As president, Seybolt did not confine himself to his office or boardroom. Like the director, he began to make a habit of touring the Museum, encountering staff members from every department, and taking a seat beside them in the staff dining room. “He was nosy and pokey, and very pompous,” recalled the Museum’s graphic designer Carl Zahn, who had contributed significantly to the fresh image of the Museum under Rathbone. “He would always buttonhole me as if he was my boss.”30 Others were bold enough to remind Seybolt that they answered not to him but to Rathbone. He seemed to be looking for holes in the system and signs of inefficiency at every turn. “You felt somehow disapproval in his every glance,”31 recalled Rathbone’s secretary Virginia Fay. To the staff, Seybolt was a stern and overbearing figure. Furthermore, he was becoming increasingly uncomfortable with the fact that, as he put it, “the actual management of the museum and really all of its force came from the director.”32

Soon he began to create a deluge of memoranda that landed on Rathbone’s desk at an alarming rate – with questions, calculations, and propositions that demanded an immediate response – and he popped up on the trail of the director’s movements throughout his busy day. “I’m here because you’re here,” he would say, wrapping one arm around him, and, “You’re a great guy,”33 giving him a punch in the shoulder. Eleanor Sayre, curator of prints and drawings, recoiled at Seybolt’s gestures of intimacy and regarded them skeptically as a power tactic. “Seybolt grabbed me in his arms and kissed me, wanting to show his power over me,” she recalled. Sayre could see that the new president intended to run the Museum himself, even though “he knew absolutely nothing about art or museums.”34 As Seybolt made his personal study of the Museum’s management, he was fascinated by Rathbone’s involvement with every single detail, and by the continuous parade of staff members in and out of the director’s office. “Mr. Rathbone was the boss,” said Seybolt. “Practically all decisions, by his admittance, even to the placing of the guards in the museum, had been observed or directed by him.”35

Tamsin McVickar, administrative assistant to the director, 1960s.

Virginia Fay, administrative assistant to the director, 1960s.

Rathbone needed plenty of air, and Seybolt didn’t seem willing to give him, or anyone else on the staff, the space to breathe. While the trustees were the custodians of the Museum, they were not responsible for, nor greatly aware of, its day-to-day operations, and this, to Rathbone’s mind, was as it should be. His most sensitive task was in the direction of his curatorial staff, and this he did with a keen instinct for the curatorial mind and a singular talent for inspiring its heart. “He was in and out of every curatorial department at least once a week,” remembered Laura Luckey, an assistant curator in the paintings department, “lifting everyone to a different level. Nobody slouched around; we all worked hard.”36 While he kept in close touch with his staff, he also gave them “a great deal of latitude,” and in responding to their problems or questions, “he was very approachable,”37 remembered assistant curator Lucretia Giese.