Читать книгу The Boston Raphael - Belinda Rathbone - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe Greatest Adventure of All

FLORENCE, ITALY, 2005

IT WAS THE EVE of the Feast of San Giovanni, and Florence was thronged with tourists. My sister Eliza, my cousin Cecilia, and I had arrived the night before, booked into a room at a small hotel in the heart of town, and spent the morning visiting favorite sights. The Bargello, with its quiet courtyard and timeless treasures, including Donatello’s bronze sculpture of the triumphant David in a feathered hat; the tiny chapel of the Palazzo Medici Riccardi, where Benozzo Gozzoli’s frescoes envelop the visitor in a rich landscape through which the Magi make their journey to Bethlehem; and the Medici Chapel, where Michelangelo’s monuments to the great patrons of the Renaissance preside over his brooding allegories of Dawn and Dusk, Day and Night. We stopped for lunch at a local restaurant, practiced our Italian (Cecilia’s fluent, Eliza’s passable, mine nonexistent) on a cheerful waiter, ordered the spaghetti del giorno, and drained a carafe of vino della casa. But now it was time to make our only scheduled appointment. We threaded our way through the crowds of sightseers, street performers, and peddlers on the Piazza della Signoria and bypassed the line of visitors at the entrance to the Uffizi Gallery, all waiting their turn to stand before some of the greatest treasures of Western art in the world. Through a door at the far end of the East Wing, we entered the quiet seclusion of the staff entranceway.

Our appointment was with one small painting, at one time attributed to Raphael, that was not on view to the public. A receptionist at the desk called for Giovanna Giusti, the curator with whom I had been corresponding by e-mail since March. From her I had learned that the picture – which had dropped out of sight more than twenty years before – was, in fact, at the Uffizi, that it was in storage, and that it would require special permission to see it. The date was set: three o’clock, June 23. There we were.

On a midsummer day thirty-six years earlier, about 150 miles north of where we stood, another party had gathered around the very same painting. My father, Perry T. Rathbone, was considering its acquisition for the Museum of Fine Arts, in Boston, where he was then director. This would be a coup for the MFA, which was about to celebrate its centennial year, 1970. Nothing could adorn the centennial celebrations more than a previously unknown work by one of the greatest artists who had ever lived. Nothing could crown my father’s fifteen-year directorship of the MFA more gloriously than such a treasure.

The party had converged from various points: from Boston, Perry Rathbone and Hanns Swarzenski, the MFA’s curator of decorative arts, who was the first to have seen the picture and to urge Rathbone to consider it for the MFA; from Paris, John Goelet, a young museum trustee with deep pockets; and from London, John Shear-man, a professor of art history at the Courtauld Institute of Art, generally regarded at the time as the foremost expert in the work of Raphael. Their appointment was with Ildebrando Bossi, a Genoese art dealer from whom Swarzenski had already bought a number of Renaissance works of art for the MFA.

They were full of excitement at the prospect. “In Genoa,” my father wrote to my mother on July 15, “we made our rendezvous with John Shearman on the dot and thus commenced the greatest of all adventures – negotiations for the Raphael,” to which he added in big block letters “(CONFIDENTIALLY).”1

It was indeed the greatest of all adventures. In fact, it was the beginning of an art-world cause célèbre of international scope, a milestone in the history of art collecting, and also the unraveling of my father’s thirty-two-year career as a museum director.

We waited in the dusky entranceway for Signora Giusti to appear. Greetings in both languages came eagerly to the fore as a sturdy middle-aged woman arrived at the desk. She guided us out the staff door and across the piazza, through another giant door into the West Wing, and up a wide stone staircase. Upstairs the walls were lined with metal racks upon which old master paintings were hung floor to ceiling. A white-smocked preparator led us farther into a small, windowless room. Standing at a worktable, he folded back the white tissue paper around a small portrait on a panel – just 10½ by 8½ inches – unframed, as starkly naked as a patient on an operating table.

I remembered her well – a young girl of about twelve or thirteen, impeccably dressed in rich velvet and lace, decorated from headdress to belt in exquisite Renaissance finery. Her name was Eleonora Gonzaga – at least it was the last time I had seen her – and she was of noble lineage, the daughter of the Duke and Duchess of Mantua. If there was a difference in my fresh impression, it was that she looked somewhat colder and cleaner, as if nothing beneath her impeccable jewel-like surface was left to be penetrated. Her trace of a smile and her steady gaze – poised and confident, but with the innocence of adolescence – betrayed little of her life to date and nothing of her travels since. She was as mysterious as ever.

The painting had been sent to a conservation lab in Rome following its return from Boston some years earlier, where it was cleaned and closely studied by various experts. At that time, said Giusti, choosing her words carefully, “the consensus was that it is not by Raphael.”

Expert opinions just a few years earlier than that had been quite different. “Before lunch the verdict was delivered,” my father wrote to my mother on July 15, 1969. “A genuine early Raphael.”2

From being quite sure that it was an early work of Raphael, to being quite sure that it was not, the trend of expert opinion rode the waves during the painting’s brief thirteen-month period of public exposure in Boston. At the same time, another struggle, equally if not more diverting, was over the manner of its exportation from Italy and arrival in Boston.

The little portrait had become the object of a contest, which usually means that only one side can win. While its acquisition was designed to serve one purpose – as a centennial prize for the MFA and the crowning acquisition of my father’s tenure – its return to Italy served another – as a trophy for Italy’s top art sleuth, Rodolfo Siviero. For the purposes of both parties, it was imperative to believe in its attribution to Raphael. But once the struggle for ownership was settled, in favor of Italy, the debate over its attribution left the international arena. The last time the picture was publicly exhibited was at the Palazzo Vecchio, in Florence, in a memorial exhibition to Siviero after he died in 1984. The wall label accompanying it stated noncommittally, “Attributed to Raphael.” Many visitors saw it there for the first time, and some remembered the controversy surrounding it. The label begged the question, and they came to their own conclusions, or not. While the picture still represented one of the most celebrated of Siviero’s repatriation efforts, it was no longer officially considered a Raphael. All that fuss, and it wasn’t a Raphael after all?

What had been a widely aired embarrassment to Boston had become a somewhat lesser and soon forgotten embarrassment to Italy. Perhaps this is what I sensed behind the manner of Signora Giusti. While its ownership was by now apparently beyond dispute, the picture was still tainted with the struggle over its cultural patrimony, which now seemed even more ironic given its consignment to storage. For all intents and purposes, it had been successfully buried. Our little pilgrimage and its brief resurrection had ruffled her feathers.

“If not by Raphael,” asked Cecilia, “then who?”

“Emilian School,” pronounced Giusti.

“What about the girl,” I pressed, “her identity?”

“Unknown,” she answered without a pause.

After we had stared at the painting as long as we politely could, I made a snapshot, and the man in the smock wordlessly folded it away. We groped for more information about the intervening years and the expert opinions that had been visited upon it. Obligingly, Giusti led us away to her small office, where she operated from a crowded desk surrounded by stacks of books and piles of papers, and shared with us articles from the Italian press on the subject of the “Rafaello di Boston.” She hurried in and out of the office to the photocopier down the hall and returned with piles of copies for each of us. The longer we spent in her company, the more her tone became defensive and hurried. The more questions we asked, the shorter her answers. She performed with the patience and armor of a carefully instructed civil servant, but her act was under strain. Finally, she summarized. Any research we might carry forward from there, she assured us, would only lead to the same conclusion. There was nothing left to say, and there was nothing left to do. The painting had left Italy illegally, and it was no longer considered a Raphael. She politely reminded us that the holiday weekend was upon her. We bade our bilingual good-byes and thanked her for her time, and with that she led us through a back door into the early Renaissance galleries for what was left of the afternoon.

What had we come in search of anyway? To revisit the object that led to my father’s downfall, as if gazing upon it might deliver some kind of resolution? Was it a ritual we needed to perform to achieve what we now call closure? Or was it simply, at long last, to answer the question that occasionally arose at the family dinner table when the subject of the Raphael came up for review? What had they done to it in the laboratory? What had they discovered, and how definitive were their conclusions? And where was it now? After a protracted and bitter struggle over getting it back, the Italians had done exactly what my father had most feared: they had made it their hostage. They had buried the story, along with the deposed work of art. The case was closed, and the trail was cold. Confirming this reality in person felt somewhat anticlimactic, like visiting the grave of someone you were already quite certain was dead.

But a few months later, the reaction of certain experts gave the story an unexpected lift. “I felt the picture had been swept under the carpet,”3 said Nicholas Penny when I visited him in March 2006 at the National Gallery of Art, in Washington, where he was then head of European paintings.4 For Penny, a deeply knowledgeable and refreshingly outspoken Englishman, his firsthand encounter with the little painting had been a formative experience. He had first seen the painting when it was unveiled in Boston, in 1970. At the time a graduate student in art history at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London, Penny was on a visit to Boston with his American bride. Fascinated, he had carried home a small color reproduction of the painting he had bought in the museum shop. After following the story of its demise, he later published the image in his 1983 book, Raphael, with Roger Jones, identifying the artist as “perhaps Raphael.”5

“My intention was to bring it back to light,” said Penny. “Even if it’s not by Raphael, it’s still a very interesting picture.” But Penny remained puzzled by the fact that my father had approached just one Raphael scholar for an opinion – John Shearman, who had been Penny’s professor at the Courtauld. Had Rathbone consulted others, he might have been on firmer ground. Was it his commitment to confidentiality that made him play his cards so close to his chest? Was it Shearman’s well-known tendency to isolate himself from his fellow scholars? Either way, would a second opinion have strengthened, or weakened, the case? No matter what, Penny surmised, in a case of a precious and rare picture believed to be the work of a great Renaissance artist, it had been “fatal to go the lone path. . . . What you underestimate are the weapons that are being sharpened with envy.”6

Not long afterward I spoke with another Raphael scholar, Paul Joannides, at the University of Cambridge, who saw the picture for the first time at the exhibition at the Palazzo Vecchio in 1984. “I would tend to think that Shearman was probably right,” he told me. The picture, he observed, possessed qualities much like other early works of Raphael – the moon face, the small almond eyes. “It’s not a very penetrating portrait,” he admitted, and if it were, in fact, by Raphael, “it would not do him a great deal of credit.” On the other hand, he suggested, “there are people around Raphael not yet defined, and the picture could be the work of another artist of the period we have yet to discover.”7

By the time I embarked on my research, it was too late to meet John Shearman, who died in August 2003. A few months later, simply out of curiosity, I attended his scholarly memorial service at Harvard. In the bright and businesslike Faculty Room at University Hall in the middle of Harvard Yard, his loyal students and colleagues gathered to remember his contribution to the field. I listened for signs of the Boston Raphael story. But it quickly became clear that, while Shearman had continued to work extensively on Raphael at his various posts – as professor at the Courtauld, then Princeton, and finally Harvard – he had successfully buried the Boston Raphael in his past, surely embarrassed by the storm of publicity surrounding it, the challenges to his scholarship, and perhaps not least, the disaster his attribution had caused the Boston museum.

My parents staunchly believed in the injustice of the episode for the rest of their lives. They moved on, but it was like a cloud that had never completely blown away, a permanent blot on my father’s otherwise fine reputation, a heartache that every so often acted up again and required soothing. They would review the details and recastigate the characters they blamed for the fiasco. Most of all, my father blamed the Italian government for reclaiming a work of art that they ultimately had so little use for. “It was absurdly handled,” my father told an interviewer in 1981, “and someday, if I live long enough, I hope to have the strength to write about it.”8 To another interviewer he went as far as to say that he believed that someday the picture might return to Boston.

My father did not live long enough, nor perhaps would he have ever had the strength to write about it. Instead, the press version of “the Boston Raphael” trailed him for thirty years, all the way to his obituaries when he died in January 2000. For all his many successes, this fiasco remained, as he himself had called it, the greatest adventure of all.

But while the superficial press version of the story bothered me, so did my father’s obviously subjective account. Furthermore, the story was incomplete; there were many aspects of its outcome that remained mysterious, even to him. Meanwhile, the carapace of family myth hung stubbornly around it, obscuring further details, a web of ethical issues too delicate to untangle, discouraging further questions too painful to raise or to investigate. While I understood his motives implicitly, I could not help but wonder: Where had his judgment gone wrong? If character is destiny, what aspects of his character had brought him into the crosshairs of this life-changing event? Was the Raphael the only reason for his abrupt departure from museum work? To what extent was he the victim of circumstance, of changing times, and of a cluster of conflicting personalities closely involved in the case? How could the ground have shifted under him so suddenly? Or had it been shifting, imperceptibly to him, for years?

In his prime, Perry Rathbone was one of the most influential museum directors in America – a connoisseur of great breadth as well as a brilliant showman. Over the course of thirty-two years he played a crucial role in the modernization of the American art museum, transforming them from quiet repositories of art into palaces for the people. As director of the City Art Museum of Saint Louis (now known as the Saint Louis Art Museum) from 1940 to 1955 and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts from 1955 to 1972, he ambitiously moved both museums forward into the postwar era. He staged unprecedented loan exhibitions, and with his flair for publicity, he attracted record crowds. He brought light and life into the galleries and expanded and improved auditoriums, restaurants, and gift shops. He established committees of women volunteers and with their help invigorated museum programs with films, lectures, and special tours both local and abroad. Under his leadership, attendance and membership increased exponentially, and consequently so did revenue. In Boston his staff tripled, the budget quadrupled, and the annual sale of publications increased more than 1,000 percent. These were achievements of which my father was justly proud, but he knew that numbers were not the only measure of success. More than anything, he was proud of the acquisitions he had made for the museums’ permanent collections. His career had been ascendant in every way, until the end. To this day many observers continue to wonder how the dean of American museum directors could have made such a fateful and avoidable error of judgment. More than one person has reflected that, in the manner of Icarus, Perry flew too close to the sun. Still others have called the behind-the-scenes drama at the MFA Shakespearean in the scope of its moral struggle. Some viewed Rathbone as a tragic hero, a martyr to the museum cause. As one former colleague said of his fall, “Perry had to take it for the whole rest of the art world.”9

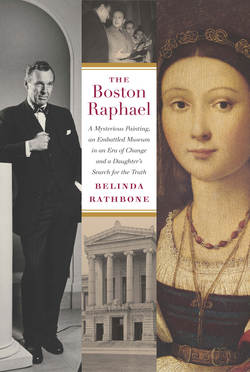

Perry T. Rathbone celebrating fifteen years as director of the MFA with staff members (left to right) Lydia Calamara, Mary Jo Hayes, Virginia Nichols, Hanns Swarzenski, Jan Fontein.

A born optimist, Rathbone’s enthusiasm for art was infectious, and his powers of persuasion seemed almost limitless. His tall, impeccably dressed figure matched his commanding voice and ready eloquence. His democratic air exuded the spirit of his motto, “Art is for everyone.” With his youthful good humor and his genuine interest in people, he conveyed this belief naturally and effortlessly, surrounding wherever he stood with an aura of excitement and festivity. In addition to his formidable day job, he accepted invitations to boards of trustees, professional associations, and panels of experts, as well as invitations to lecture, write, and jury. He not only enjoyed these roles but also felt an obligation to be a part of the urgent, ongoing discussion, to speak out for what he believed in, and to take the heat when it came. On top of this was his nonstop social life, which he regarded as an essential part of his job and, fortunately for him, on which he personally thrived. In retrospect, how he fit all these activities into an average day remains hard to imagine. He lived life as if to defy the natural limits of one man.

Rettles de Cosson, #13, Murren, Switzerland, 1937.

Of course, there was a woman behind the man – his wife and our mother, Euretta “Rettles” de Cosson. Born in Cairo to an English father and American mother, Rettles spent her childhood in Egypt and later attended schools in England and finally Switzerland, where she became a passionate skier. Soon afterward she started training as a downhill racer. After winning several races in Switzerland and Austria, Rettles was made captain of the British women’s team in 1938 and then again in 1939, and she looked forward to entering the Winter Olympics for the 1939–40 season, to be held in Germany. But this would not come to pass. When Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, the Olympics were canceled, and Rettles found herself stranded in the United States for the duration of the war. By a fortunate piece of timing Averell Harriman had just opened a ski resort in Sun Valley, Idaho, earlier that year. Rettles signed up to race against the American women’s team and spent the winter of 1940 in Sun Valley. Hailed as “Britain’s most fearless skier,”10 she lived up to her reputation for daring and perseverance. Despite taking a bad spill in the 1940 races for the Sun Valley Ski Club, she nosed out her American competitors and a year later earned the prestigious Diamond Ski.

It was in the wake of this triumph that Rettles first visited Saint Louis and met Perry Rathbone, the young director of the City Art Museum. Then and there she set her sights. Their wartime courtship began in earnest when they were both stationed in Washington, Rettles working for the British Information Services and Perry for the United States Navy Publicity Office. Over the course of several months, Perry fell in love with Rettles’s quiet worldliness, her fascinating background, and the independent and competitive spirit that rumbled beneath her shy demeanor. They were engaged on the eve of his departure for the South Pacific in May 1943. Thus, at the relatively advanced age of thirty-four, Rettles de Cosson won another race against the American competition: landing the most eligible bachelor in Saint Louis.

From a child’s point of view, my father towered over us, both physically and as an example of how to live passionately for one’s vocation and give it one’s fullest potential. There was no question that he was a figure we were supposed to live up to, and my mother reinforced this perception subtly but unwaveringly. We were his entourage and his cheering section. We walked in his glow, shaded and also sheltered by his fame. Like the family of any public figure, we were expected to understand and support his side, for we were a part of his identity. Wherever he went, he showed us how the individuals he encountered played an important role in his life, hailing the florist in Harvard Square, the chemist, and the gas station attendant like old friends.

It was exciting to be treated as insiders in his castle of work. I remember visiting him in his office, a huge high-ceilinged square where he operated behind a spacious desk, face-to-face with his latest object of desire on the opposite wall – Tiepolo’s terrifying Time Unveiling Truth; Monet’s delightful La Japonaise; the riveting, anonymous Martyrdom of St. Hippolytus; ter Borch’s soulful Horse and Rider. Occasionally, at the end of his day, I might be invited to trail after him on his rounds through the galleries, his brisk pace matching his omnivorous, critical eye. I practically ran to keep up, often losing track of how we got to where we were and in which end of the enormous building we found ourselves. Always he wanted to know what I thought and seemed to take my opinion to heart. And always he ventured to point out what was new in the way of an acquisition or fresh installation – his latest achievement. So I grew up with an uncommon sense that the art museum was in a continuous state of renewal and change. Things happened there for a reason, not by chance. Someone was at the helm, and that person made all the difference.

He was constantly guiding us on how to see a work of art and what made it wonderful. He preached a discriminating eye for quality but also openness to every kind of creative effort. At home as well as in the Museum, every object, every work of art or piece of furniture, had a background, its own story to tell; each was an emblem of our parents’ mythical past. The vulgarities of mass culture were held at bay. Comic books, junk food, chewing gum, and Coca-Cola were not allowed in the house, and television viewing was strictly limited. We were the upholders of high culture and hallowed tradition in a crass and commercial world, and we were clearly outnumbered.

Then there were the parties he and my mother hosted at our home on Coolidge Hill in Cambridge before the important evening events at the Museum. From the arrival of the help in starched uniforms (William Swinerton, a former butler from Ham House in England, and his wife made an incomparable team), to their invasion of the family kitchen, the bustle of dinner plates and glasses through the swinging pantry doors, to the animated banter, laughter, wafts of Guerlain, Chanel, and cigarette smoke mingling and rising to the upstairs landing, where we huddled, fascinated, to the gentle roar of guests bidding their good-byes in the front hall – that this was a glamorous and exciting world they inhabited we had no doubt.

Every July we welcomed my father home from Europe at Logan Airport, an event we looked forward to with great excitement. He would have a little something in his suitcase for each of us – a handmade souvenir from one of the countries he had visited – and we knew there were other surprises in store that he would keep in the bottom drawer of his dresser for later occasions. Over dinner we would beg him to tell us stories of his adventures abroad – the wonders of art he had seen, the interesting or odd people he had met, the mishaps and the chance encounters of his hectic travels. On our own occasional long summers abroad, between our mother’s carefully planned visits with friends and relatives all over the map, we joined him here and there for a bout of intense sightseeing, with varying degrees of enthusiasm, depending on our age, as he attempted to teach us patience in the presence of greatness.

Rathbone family group passport photo. Clockwise: Rettles Rathbone, Belinda, Eliza, Peter, 1954.

At Christmastime one of the great thrills of the season was to accompany him to Bonwit Teller, the most elegant women’s clothing store on Newbury Street. Straight to the second floor my sister and I would follow him to the designer dresses, where saleswomen in suits and lacquered hairdos circled around my father as if he were royalty, presenting him with the latest evening dresses as if they were one of a kind, inquiring would this one or that one most become Mrs. Rathbone? My father sized them up like works of art, engaging the ladies in animated conversation. He loved to shop as much as my mother hated it. She allowed him the pleasure of choosing, of enhancing her trim, athletic figure and her classic beauty, and, for the sake of his vanity perhaps more than her own, she always saved the biggest surprise under the Christmas tree for last.

As a member of the first generation of Harvard-trained museum professionals, my father was part of a postwar revision of the very concept of the American art museum. In his time, his achievements were clear to see and widely known. But by now they are nearly invisible, folded into the many layers of change since his heyday, forgotten amid their endless subsequent iterations and installations. Before setting out on the long path of his career, his mentor at Harvard, Paul Sachs, offered these cautionary words: a museum director’s life is written in sand.

In his retirement from professional life, which he accepted gracefully but reluctantly at seventy-five, my father continued to ply his folders and file cabinets with an unanswerable yearning to turn their contents into something meaningful and readable, to tell his story. But he was wary of the enterprise. He looked on, skeptically, as other museum directors of his time wrote their memoirs, which, while valuable, were also inevitably as self-serving as they were politically handcuffed. Of one thing he could be sure – that his life and times were carefully preserved in the archives of the museums he had served, as well as in the boxes and file cabinets and trunks at home full of personal letters, journals, press scrapbooks, and photo albums that he had kept faithfully throughout his life. In addition, two lengthy interviews were conducted after he retired from the MFA: one for the Archives of American Art in 1977, the other for the Columbia University Center for Oral History in 1981. It may have been too late for him to write his memoirs, but he left us – my brother, Peter; my sister, Eliza; and me – with a minutely documented trail. He had done his utmost to show us – and anyone else who might care – the way back to his true story, to make of it what we would for ourselves. As I stepped into the mass of evidence of his success, I was also freshly alerted to his many challenges. And as I began to investigate other individuals close to the scene, his point of view was countered by those of others. What emerged beyond my own impression of a benign and beloved leader was a figure in the constant heat of the spotlight, and one who was far more embattled and controversial than I had imagined.

Classical Galleries before renovation, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1960s.

How could it be otherwise? As a public servant, a museum director is fair game, inevitably the object of criticism for the museum’s shortcomings as much as the object of praise for its success. A new generation of museum directors continues to redefine the profession – to confront the latest demands of the public, improve on the physical plant, expand public programs, refine connoisseurship, conserve and build the collections, all the while and ever in search of a path to financial stability. Today’s museum directors face many of the same challenges as those of the past, but no matter what, as Paul Sachs warned his museum studies students at Harvard, their work will be written in sand. Other castles have been built where my father’s once stood, and other people have claimed responsibility for the innovations he stood for, as if for the first time, but in retrospect only in a new way, on a new scale, for a new age. In understanding the story that follows, it is essential to consider its many ramifications within the context of its times.

New Classical Galleries reinstallation, 1967.

Meanwhile, among the dwindling fellowship that remembers it at all, mystery, rumor, and misunderstanding still surround the story of the Boston Raphael, as well as a crust of inevitability that was only formed in hindsight. Our visit to the Uffizi was the first step backward into a matrix of circumstances that paved the way to this landmark series of events. If it was the story my father least wanted to be remembered for, it was also the one he most wanted fully told.

This is not the book my father would have written, though his words have been a constant guide in the writing of my own. If he were still with us, I would have perhaps gained further insight into the workings of his mind at that time and access to a few pertinent facts that still remain mysterious. At the same time, it would have been impossible to attain the degree of objectivity necessary to tell the story in its many facets. I embarked on my research with some trepidation, not knowing what I would find, and in the face of my siblings’ grave concerns about the enterprise. From their point of view (and that of many other friends), the less remembered – much less written – about this unfortunate incident, the better. But since returning to live in Boston, I was perhaps more aware than they how inaccurately it was recalled and how generally misunderstood it was in the first place. There was nothing that mattered more to my father than historical accuracy in fact and context, and there was nothing that bothered him more than uninformed and casually drawn conclusions.

In my research into primary and secondary sources, I have sought to understand the circumstances surrounding the story of the Raphael with an open mind. While some mysteries remain, I have not knowingly left anything significant out of the story. I have sat with the enemy and absorbed the shock of learning that there were other ways of looking at the same events and the same personalities than the ones I was raised to believe. At the same time, I have carefully weighed each personal account for its degree of truth against accounts of the same events – both conflicting and corroborating – and endeavored to size up each witness for his or her inclinations and sympathies. Even in my father’s absence I have had to fight the natural reflex to defend him from criticism. For all my striving for objectivity, there is no escaping that I have come to this work with a point of view about the politics of the art world, and one that was clearly honed by the subject himself. But in reliving those years we lived together, as both biographer and witness, I have come to understand them as if for the first time. My point of view by now comes with a background of evidence, and now I understand in all its fullness what before I had simply taken on faith.

Crowd in line for The Age of Rembrandt exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, January 22–March 5, 1967.

Crowds at The Age of Rembrandt exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, January 22–March 5, 1967.

The story of the Boston Raphael is inseparable from another story. No small part of this event was the political turmoil brewing within the institution itself in the late 1960s – a museum in the flux of change, in the throes of ideological conflict, as its size, its scale of operations, and the value of its collections reached a tipping point, the point at which the modern art museum was becoming the postmodern art museum. The philosophical questions of that bygone era are still urgently with us today, even as the landscape has vastly changed. The conventions of exporting works of art, the methods of research and authentication, the ways that museums are managed and the priorities that have recently overtaken them – all three of these issues turned a decisive corner during and in the immediate aftermath of the Raphael affair, just as they played out as elements in its outcome.

“How well did you know him?” a former member of the MFA’s Ladies Committee asked me not long ago. The question took me aback. Did she mean that no one could know a father who was always on the job? Did she mean that she knew him better than I did? Had she forgotten for a moment whom she was talking to? Or was it a provocative question, the one I was constantly asking myself as I reviewed the archives of his life, seeking to understand him differently, objectively, while also knowing him, as a close witness to those troubled times, and as only a daughter can?