Читать книгу The Boston Raphael - Belinda Rathbone - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

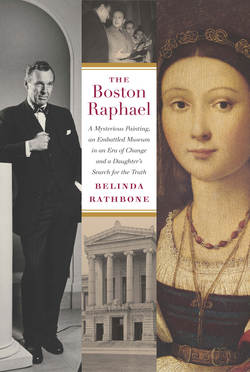

ОглавлениеThe Making of a Museum Director

IN 1921 HARVARD INTRODUCED a yearlong graduate course led by Professor Paul Sachs called Museum Work and Museum Problems. Better known as simply “the Museum Course,” it has since become legendary, the first and by far the most influential of its kind in America.

The idea for the museum course came to Sachs in consultation with the secretary of the Metropolitan Museum, Henry Watson Kent, a high-flying innovator who routinely transcended his nominally administrative role. Kent perceived the urgent need to educate a new generation of museum professionals. Art museums in America were growing rapidly, and new museums were opening all over the map. Searching for a younger generation of properly trained “museum men” (in those days, they were assumed to be men) ready to address the challenges of the day, Kent found they were nonexistent, and he urged Sachs to do something about it. “I find I know no one who seems to meet the demands,” wrote Kent to Sachs, “which are that he be understanding in how to organize, popularize, and advertise a museum; that he should be a gentleman of some presence and force; that he should be very sympathetic with the situation as regards the creation of the right kind of spirit and sentiment; that he should be thoroughly qualified also along the lines of collecting, with a knowledge of values; that he should have knowledge of the possibilities of borrowing.”1

Kent had decided that Harvard, with its first-class art faculty, libraries, and a burgeoning teaching museum, was the natural place to lead the way.

In the formation of his course, Sachs endeavored to train the scholar-connoisseur, adding to this essential quality hands-on instruction on a museum’s day-to-day management. The course began experimentally and informally in 1921 with a few students and proved an instant success. Early graduates of the course included Alfred Barr, the first director of the Museum of Modern Art; James Rorimer, director of the Metropolitan Museum; John Walker, director of the National Gallery in Washington; and John Coolidge, director of the Fogg Museum. For nearly thirty years Sachs single-handedly trained a generation of museum professionals, including Perry Rathbone, who entered in the largest class to date in 1933.

By the time the museum course had begun, Edward Waldo Forbes had paved the way. Forbes was from an old Boston family, the grandson of Ralph Waldo Emerson on his mother’s side, while his paternal grandfather was the China trade capitalist John Murray Forbes. Spending his summers on the island of Naushon in Buzzards Bay, Edward developed an enduring respect for nature and a lifelong hobby of painting en plein air. As the first director of the new Fogg Museum,2 Forbes placed an unprecedented value on connoisseurship and conservation. He emphasized the importance of the students’ firsthand acquaintance with authentic works of art, a privilege he himself had not enjoyed as a Harvard undergraduate, when art history classes relied primarily on black-and-white reproductions.

At Harvard, Forbes had studied under Charles Eliot Norton, the first professor of art history at the college, who emphasized the relationship between fine arts and literature. Norton’s course, like that of his close friend John Ruskin at Oxford, was largely theoretical, as much about society, literature, and ethics as about visual art. But being a child of the industrial age, Forbes, like many of his contemporaries, was also drawn to the “aura of the original.” After graduating from Harvard, he traveled in Europe, absorbing as much as he could of the real thing. In Rome he struck up a friendship with Norton’s son Richard, who was teaching at the American Academy. Norton persuaded Forbes to assemble a collection of Renaissance paintings to put on loan to the Fogg for display. With this advice, his lifelong relationship with the Fogg began.

Forbes thus set an example, which led to gifts of important works of art to the Fogg’s collection from other wealthy Harvard alumni, welcome additions to the fledgling collection of plaster casts and a small group of traditional paintings gathered by the Museum’s original donors, Mr. and Mrs. William Hayes Fogg. New gifts from Forbes and others were so numerous by 1912 that plans were made for a new museum adjacent to Harvard Yard on Quincy Street. As director, Forbes conceived of the new Fogg as a laboratory of learning, accommodating galleries, lecture halls, curatorial offices, conservation, and a research library all under the same roof. He closely oversaw the architectural plans by Charles Coolidge – from the outside, a simple brick neocolonial; inside, a spacious, skylit courtyard modeled, down to the last detail, on a High Renaissance facade in Montepulciano, in Tuscany, creating a sanctuary from the day-to-day bustle of Cambridge. Forbes insisted that this be finished, like the original, in travertine, at the then-extraordinary cost of $56,085. Harvard president Abbott Lawrence Lowell balked. A simple plaster finish would cost about $8,500. The travertine was not only expensive, Lowell asserted, it was ostentatious. But Forbes was adamant. How can you educate young people in the language of materials, he asked, if they are exposed only to cheap imitations? The debate dragged on for several months while Forbes sought financial support from other benefactors and eventually, with typical single-mindedness and patience, won his case.

Someone once described Forbes as a man of few ideas, all of them excellent. Among these was the idea to recruit Paul Sachs, Harvard class of 1900, to teach and to be codirector of the Fogg. Sachs was a New Yorker and a partner in the family investment-banking firm of Goldman Sachs. He came from a long line of German-Jewish patrons of the arts and was himself a passionate collector of prints and drawings. Having plied the family trade for a few years, he was more than willing to leave the financial world behind and join the fine arts faculty at Harvard. Forbes perceived how Sachs – already a generous benefactor of the Museum – could complement his own interests and inclinations, bringing his business know-how, as well as his extensive contacts among rich art collectors from New York and beyond. Their partnership began with Sachs’s appointment to the visiting committee in 1911. “My foot is in the door,”3 Sachs excitedly told his wife, Meta. The door opened in 1915, when Sachs was made associate director of the Fogg. This unlikely duo – one a patrician Boston Brahmin, the other from the Jewish-German financial world of New York – formed the vision and foundation for Harvard’s art department in the twentieth century, a combination with far-reaching consequences.

How did it come to pass that Perry Rathbone would fall into this exclusive lap of learning, and where had the seeds of his interest in art been sown? It was his father, Howard Rathbone, who first inspired his artistic inclinations. From infancy to age six, Perry grew up in New York City, where his father worked as a salesman for a wallpaper firm and then as a furrier, and his mother, Beatrice, was a public school nurse. Among Perry’s formative memories were family visits to the Metropolitan Museum. One unforgettable day in the American period rooms, his father told Perry and his only brother, Westcott, that the antique desk on display was certain to contain a secret drawer. To prove his point, he slipped under the guard rope, gestured to the boys to follow him, and unlatched the desktop wherein, like a magic trick, the secret drawer was revealed.

Why was this little vignette, which Rathbone fondly related to an interviewer decades later in 1982, so significant? On the surface, it tells of his first visits to an art museum, but more than that, it shows a combination of paternal traits he would cherish and inherit: a curiosity and keen interest in the arts, the audacity to break rules to get closer to a sacred object to better understand it, and the personal charm to talk his way out of trouble when necessary.

Though he did not have the benefit of a higher education, Howard Rathbone had an eye. An avid photographer, he was alive to his physical environment in its every form – from antique furniture to the scenic beauty of the countryside to the distinction of a pedigreed dog. A spry little man, he knew how to strike a pose and what to wear for every occasion. He understood the quality of materials, the subtleties of color, and the value of the little details – how to stuff the handkerchief in his breast pocket just so and how to keep the carnation fresh in his buttonhole. He was also a charmer par excellence, not just with the ladies but also with children, the elderly, or anyone who appeared to be in need of a little boost. In contrast to his practical, steadfast, long-suffering wife, Beatrice, Howard had a gift for making everyone in his orbit feel like the most important person in the world.

Howard Betts Rathbone, self-portrait, undated.

If his father inspired Perry’s artistic eye, natural charm, and sartorial savoir faire, it was his Uncle Jamie who drew out his more intellectual side, and it is he who should be credited for planting the idea of Harvard so firmly in Perry’s mind. His mother’s younger brother by ten years, James Willard Connely was a dashing figure in Perry’s childhood. A graduate of Dartmouth College, he worked for some time as a journalist in New York for McClure’s Magazine and Harper’s Weekly. A handsome young man with a mop of dark brown hair, Jamie was worldly, articulate, and intimate with writers and artists, which meant that he frequented the colorful bohemian circles of Greenwich Village. As a bachelor living in a rented room, he was also happy to accept the occasional home-cooked meal (even under the critical eye of his sister, Beatrice) and to entertain his rowdy, redheaded nephews. At the time the Rathbones lived in a small apartment on 141st Street in Washington Heights.

Years later Jamie recalled the fine spring day in 1928 when the question of Perry’s academic future was more or less settled. By this time the Rathbones had moved from the city to New Rochelle, where Perry was enrolled in the public high school. It should be mentioned here that the family’s hopes had now been transferred to their younger son, after their firstborn, Westcott, had been expelled from every school in town for failing grades and misbehavior of one kind or another, winding up his high school years in a strict Catholic seminary. Weck, as he was known, had always been an antic, hyperactive child whose severe case of dyslexia, not yet widely known, went undiagnosed and whose penchant for entertaining his friends with clowning served only to aggravate his weak academic performance. Perry, conversely, had quietly worked hard at his studies and had shown signs of a higher ambition, a willingness and an ability to go the distance to reach his goals. Though somewhat shy compared with Weck, slight in build, and less talented at sports, Perry now towered over his older brother in height and in stature. For years Weck had hogged the limelight, but once in his teens it was Perry’s turn to shine.

Sharing a picnic with the Rathbones on the rocks of Long Island Sound one spring day, Uncle Jamie (as he himself recalled) was wearing his brand-new bowler hat from Bond Street, which he felt sure “heightened [his] avuncular mien.” The question of Perry’s future came up for discussion. While his performance in mathematics and science left something to be desired, he showed a keen interest in literature and a talent for acting and public speaking as well. Most of all Perry showed a talent for art, consistently contributing his pen and ink drawings to various student high school publications. But there were considerable doubts in both Perry’s and his parents’ minds that his artistic talent was “firm enough to build upon a career as an artist.” His uncle set out to strategize. He should study fine arts. At Harvard. Where else? And then seek a post in a museum. “On that path,” Jamie argued, “he could move for life in the well-remunerated circles of art, enjoying all the atmosphere and congeniality of it without being required to produce it.”4 Jamie felt quite sure that he had made an impression on the whole family. In hindsight, it seems that he had.

While in academic terms Perry’s high school record was unspectacular (he graduated 178th in his class of 235), his sixteen-year-old heart was thus set on Harvard. “I wish to go to Harvard,” he wrote in his application, “because, from what I have seen and learned of the college . . . I know that the Fine Arts course is exceptionally good.”5

Perry, Beatrice, and Westcott Rathbone, c. 1929.

The Rathbones would be stretched to meet the costs of a Harvard education – in 1929 tuition was $400, and residence costs added another $350. Westcott had already laid claim to $800 of the family’s resources for studying music (an interest that did not last), while their parents’ combined income was a modest $7,000 a year. Perry applied for financial aid with letters of support from his high school teachers. Perry was “a manly, well-bred, and splendid fellow,” said one, “who has a real capacity for exerting the right kind of influence among his fellows.” Perry came from a family of “old reliable New England stock – the kind who do the right thing.”6 His English teacher added that he was a boy of the highest moral qualities. “I notice it in particular in English class in our discussions in which he always supports the right side,” she wrote, and she made the point that this took courage in the face of “possible ridicule from the other boys.”7 Despite financial needs and fine moral character, Perry’s application for financial aid was denied, but the show of support for his case might have also been exactly the degree of extra weight his application needed to succeed. In July the letter arrived. Perry was accepted into the Harvard class of 1933. Somehow his parents pulled together the necessary funds, and he entered his freshman year in September 1929.

Once he was admitted, his father offered a candid appraisal of Perry’s strengths as well as frankly admitting his shortcomings. “[Perry] is a splendid worker in channels he is interested in,” he wrote, “but a very rank procrastinator in the things that do not interest him.” What interested him was art; he exhibited a gift for drawing and “a great craving for knowledge of both the old and new artistic worlds.”8

It was only a matter of weeks after Perry arrived in Cambridge before the stock market crashed in October 1929. But Harvard was a safe haven during those early years of what was to become the Great Depression, a highly civilized way of life and a sanctuary of learning far removed from the concerns of making a living. President Lowell, in charge since 1909, had recently completed his most far-reaching accomplishment: the house plan. New housing had been badly needed to accommodate the growing student population, which had doubled in the late nineteenth century, and Lowell had seized the chance to design an inner structure for the much larger college into which Harvard had suddenly evolved. The idea was to create smaller communities in the form of newly built residential houses, each with its own cultural, social, and athletic activities. In a fresh democratic spirit, an effort was made to diversify members of the student body in terms of their social and economic backgrounds. The house plan greatly improved the quality of life among the undergraduates, particularly for those, like Perry Rathbone, who were not rich enough to rent their own private digs along the so-called Gold Coast of Mount Auburn Street and who formerly would have been relegated to rented rooms in working-class neighborhoods far from the center of the campus.

Dunster House, the farthest east of the newly completed neo-Georgian houses along the Charles River, would be Perry’s home and community for his final two years at Harvard. With his roommate Collis “Cog” Hardenbergh, an aspiring architect from Minneapolis, Perry enjoyed a comfortable suite with a fireplace and three windows overlooking the river, altogether a pleasant retreat for study and a decent place to entertain their girlfriends (in those days of Prohibition, this usually meant bathtub gin) before a football game. Together Cog and Perry bought a brand-new sofa; mother made curtains, and a few other pieces came from home, including a blue-and-white tea set. Perry began his art collection with a Japanese print, for which he paid six dollars.

Meals were served in the Dunster House dining hall, where students ordered from a menu and were waited on by maids in black-and-white uniforms. No Harvard man in those days would have thought of going to a meal without a coat and tie. Nor would he have gone anywhere in public without a hat. At last Perry found himself in the kind of company he had been yearning to keep for many years. “Ever since a young child,” his father wrote, “[Perry] has gradually developed a discriminating taste as to the selection of his companions.” He admitted that his younger son’s discriminating taste was “at times almost too much so, for among certain classes he is not considered a good mixer.”9 Now among his Harvard classmates, Perry was in his element. And while during his high school years he had shown little interest in the opposite sex, the young women of Wellesley and Radcliffe Colleges were a breed apart from the small-town girls of New Rochelle.

Perry was right in anticipating that the fine arts courses at Harvard were exceptionally good, and they were only getting better. The new Fogg Museum had recently been completed on Quincy Street in 1927, and “it still had this delicious odor of fresh wax on its floors,” Perry recalled years later. Genuine objects of antiquity were replacing the reproductions of classical statuary that had filled the old Fogg, and a gift of seventeenth-century Jacobean furnishings established the Naumberg period room on the second floor. Picture collections, including Italian art of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries and a group of nineteenth-century European paintings given by Annie Swan Coburn, were also growing. Forbes’s efforts to make the building itself of the highest quality were not lost on young Rathbone, who recalled years later his first impressions of the new Fogg building: “You could see that it was beautifully designed, beautifully built, and with a great care for the materials.”10

In his freshman year Perry took a survey course taught by Chandler Post, which provided the art historical framework he would rely on for the rest of his life. “[Post] was a model art historian,” Perry recalled, “with a marvelously organized mind.”11 Post memorized his lectures and delivered them with splendid clarity. His course was well complemented by another kind of survey taught by Arthur Pope, who provided a more experimental approach to art history in the language of drawing and painting. Pope addressed the broad spectrum of visual expression across the centuries – from Indian miniatures to Greek vase painting to the revolutionary style of Giotto – providing a sense and framework for aesthetics that lifted art and its appreciation out of the purely chronological format Post supplied.

While his classmates schooled at Groton or Middlesex might have visited the great museums and monuments of Europe, Perry had never traveled beyond the mid-Atlantic states. As much as he enjoyed Post’s classes, he found himself woefully out of his depth, earning a C- in his first term. His art history courses were not the only ones Perry found challenging. German A was a bugbear, Geometry I was even worse, and Botany was a disaster. His first report came in with three Cs and two Es. Perry was put on probation and would be asked to leave if his grades didn’t improve by the end of his freshman year. His worried mother assured Dean Hindmarsh that her son was “worth educating,”12 confidently adding that by another year, when he got into his stride, he would do worthwhile work.

As his mother promised, Perry did get into his stride, eventually raising his grade level to a B average when he began to major in fine arts in his final two years. Art history courses with Charles Kuhn, George Harold Edgell, Langdon Warner, and Helmut von Erffa were complemented by a studio art class with Martin Mower, “an old-fashioned small-time painter who was a friend of Mrs. Jack Gardner,” as Perry later remembered him, and “a real aesthete.”13 In those days, the art history courses included drawing as a way of training the eye and memorizing the details, especially in the study of architecture and objects, and at these exercises he excelled.

The Fogg collection was not the only one available to the art history majors at Harvard. The Boston Museum of Fine Arts – housing one of the greatest collections in America – was just across the river, and students were encouraged to go there. The history of Asian art was just beginning to be taught at Harvard (Norton had not considered it worthy of serious study in his day), and the Asiatic collections at the MFA were world-renowned. But unlike the Metropolitan Museum, which he had enjoyed so much as a boy, Perry found the Boston museum somewhat forbidding. No one on the curatorial staff came forward to welcome the Harvard students, and certainly not the director, Edward Jackson Holmes (a direct descendant of Oliver Wendell Holmes), who was regarded as a remote and intimidating figure. Isabella Stewart Gardner’s museum, Fenway Court, was just a stone’s throw from the MFA and had a far more welcoming and fascinating atmosphere. Mrs. Gardner had been a personal friend of most of the Harvard fine arts faculty, and her museum, with its world-class collection of European paintings and its dazzling Venetian garden courtyard, was for the art-minded student “an absolute wonderland.”14

There were other outlets for Perry’s art interests in his undergraduate years. His talent for drawing or, as he put it, “my modest ability with a pen,”15 won him membership to the Lampoon. This unique club of undergraduates produced a humor magazine four or five times a year, and because wit and talent were more desirable commodities in this context than a listing in the Social Register, membership in the Lampoon was within his reach, while exclusive final clubs such as the Porcellian (sometimes called “the Piggy Bank,” referring to the exceptional wealth of its members) were not. But the Lampoon had perhaps more interesting distinctions to its credit in the long run. For a start it was housed in the most eccentric building in Cambridge – a flatiron mock-Flemish fortress at the division of Mount Auburn and Bow streets. Only members were allowed within its fabled interior, which was furnished with antiques donated by wealthy patrons, including Isabella Stewart Gardner, and finished in dark paneled walls, its vestibule inlaid with no fewer than 7,000 Delft tiles. Members enjoyed dinner there once a week in the trapezoidal Great Hall, lit from above by sixteenth-century Spanish chandeliers while gargoyle-like creatures supported lamps along the walls. Thus the Lampoon provided another inspiring interior in which to bask, as well as another social outlet, albeit, as Perry put it, “in a clubby sort of way.”16

In his junior year Perry also became involved with another kind of club – the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art. This was an experimental art gallery started by Lincoln Kirstein, Eddie Warburg, and John Walker, all seniors when Perry was a freshman. In 1928, with the support of both Forbes and Sachs, this adventurous trio claimed a couple of rooms on the second floor of the Harvard Coop in the heart of Harvard Square in order “to exhibit to the public works of living contemporary art whose qualities are still frankly debatable.”17 From the point of view of Sachs and Forbes, this undergraduate enterprise let them off the hook when it came to the untested art of the early twentieth century. They could be supportive in both spirit and funding, along with other members of the board, while maintaining their own high standards at the Fogg. Membership in the Society cost a student from Harvard or Radcliffe two dollars a year. For this they were introduced to modern art by the likes of Léger, Miró, Braque, and Picasso, whose qualities, in just a few years, would be hardly debatable at all. The Society even staged a piece of what we would now call performance art, inviting Alexander Calder to construct his circus of wire figures on the spot and then make them perform. It was a daring and audacious enterprise, true to the spirit of the times. Soon afterward, in 1929, the Museum of Modern Art opened in New York, with both Kirstein and Warburg deeply involved in its formation.

By the time Rathbone joined the staff of the Society, Kirstein and the rest had graduated and left Cambridge. They passed the leadership to fine arts major Otto Wittman, who in turn urged Rathbone and Robert Evans, an English major, to become codirectors, maintaining the original triumvirate form to the organizations. Already it had attracted a loyal group of followers, including several New York collectors and dealers willing to lend work for exhibitions. During Rathbone’s tenure the society organized an exhibition of surrealist art – the latest “group movement” – which included works by Dalí, Ernst, Picasso, and Miró. They also organized shows of contemporary American artists, including recent works by Charles Sheeler, Mark Tobey, and Stuart Davis, stressing that these Americans showed an independence from European influences. Venturing into the politically charged, they exhibited a series of prints by Ben Shahn on the controversial Sacco-Vanzetti trial. The show inspired various groups to call for the expulsion of the undergraduates responsible for it and required President Lowell to compose a public statement in their defense, making the whole event something of a sensation. At peak times the Society’s visitors numbered more than one hundred a day, and by 1933 it had become a vibrant part of the cultural life of Greater Boston.

When he graduated in 1933, Rathbone already had his eye on Paul Sachs’s highly recommended museum course. Various ideas he had once entertained – of becoming a writer, a set designer, or a landscape architect – had by now faded. Ever since taking his course in French painting in his sophomore year, he had warmed to the idea of studying further with Sachs, for whom he felt a special affection. While Sachs treated undergraduates with a certain formality, his graduate students enjoyed a more intimate relationship. Although his lectures could be somewhat pedantic – he read them aloud from a script – he was known to be at his best in the more relaxed format of the seminar.

Paul Sachs hardly looked the part of a museum man. In contrast to the rather rumpled figure of Edward Forbes, Sachs dressed like a banker, as Rathbone observed with interest, in stiff collars and dark suits. He was abnormally short – about five foot two – and when he was seated on a high Renaissance chair, his feet didn’t quite touch the floor. He had very dark, bushy eyebrows and piercing eyes, which appeared even larger behind his thick spectacles. He had a rich voice and a “very pleasant New York accent,”18 and best of all, it seemed to Rathbone, a warm heart. Everyone who took Sachs’s museum course also came to know Mrs. Sachs, whom Rathbone remembered as “rather broad in the beam, with an old-fashioned sort of chignon hairdo and a smile that stretched all the way from ear to ear.”19 Meta Sachs took a real interest in her husband’s students, and she also had the wit and confidence it took to poke fun at her husband when he acted a bit pompous.

As his students grew in number – Perry Rathbone entered the largest class to date of twenty-eight in the fall of 1933 – Sachs maintained the informality of the course’s fledgling years. On Monday afternoons he held seminars at his own home, an old federal mansion called Shady Hill just a short walk from Harvard Yard and the Fogg. Appropriately enough this was the former home of Charles Eliot Norton, the figurehead and first professor of Harvard’s art history department. In the library, which ran the length of the house in the back, Sachs arranged his books as well as various artifacts and drawers full of prints and drawings. He invited his students to appraise his private collection, identify objects, and hold them in their hands. His notion was that the student should get to feel, literally, at home with art. “There you would sit,” remembered Agnes Mongan, another museum course graduate, “with some incredibly rare object in your own two hands, looking at it closely . . . a small bronze Assyrian animal, a Persian miniature . . . a Trecento ivory . . . a small Khmer bronze head.”20

While he encouraged them to develop expertise in one particular area, Sachs declared, “Every self-respecting museum man must have a bowing acquaintance with the whole field of Fine Arts.”21 He taught his students to be curious about everything they saw and to develop an eye for the authentic. One exercise was to identify within four minutes which of a selection of objects on the table – a piece of brocade, a bronze object, a Buddha, a handle, a pestle – was actually made within the last fifty years. He asked them to select an object and make a case for its acquisition to an imaginary board of trustees. He trained them to develop their visual memories by asking them to list all the pictures on the second-floor galleries of the Fogg in the order of their appearance, adding to this their provenance, condition, and aesthetic value.

Sachs’s students also needed to understand what went into the running of a museum from inside out and from top to bottom. He asked them to make architectural renderings of the Fogg’s floor plans to better understand the particular logic of a museum building. He taught them how to catalogue collections, organize exhibitions, and write press releases. He assigned research papers on a variety of topics and added to this bibliographies, class presentations, and gallery talks. He taught them to compare collections from all over the world, to have a working knowledge of what was where. One assignment was to list every single French painting in America. It was “a hothouse treatment,”22 remembered Rathbone, one that made the students realize at once how little they had learned of the real world as Harvard undergraduates.

A museum is as good as its staff, Sachs used to say, and he meant this to apply to every level of its management. Perry observed that Sachs considered “some of our number rather too privileged,”23 and that it wouldn’t hurt them to get a taste of the less glamorous side of museum work. Sachs introduced them to janitorial duties, stressing the importance of keeping “a tidy ship.”24 Students were asked to take turns arriving early in the morning with the maintenance staff and then follow the superintendent around, dusting the cabinets and sweeping the floors.

Sachs also insisted that students be closely acquainted with artistic techniques. To that end Edward Forbes conducted a laboratory course in Methods and Processes of Italian Painting, more familiarly known as “egg and plaster.” Forbes taught them how to paint in egg tempera and how to prepare a gesso panel, how to handle the esoteric materials and how to use the tools of the old masters such as the wolf’s tooth. He introduced them to the technique of gilding, of painting on parchment, and the methods of fresco – both fresh and secco – using the walls of his classroom at the Fogg Museum as their practice ground.

They visited and reported on neighboring museums such as the Worcester Art Museum and the Museum of the Rhode Island School of Design. And during the Christmas and spring breaks Sachs led his students on field trips to New York, Philadelphia, and Washington to meet dealers, collectors, and museum curators, including some of his former students who by now were well and highly placed.

Edward Forbes’s Methods and Processes of Painting class, 1933–1934. LEFT TO RIGHT: James S. Plaut, Perry T. Rathbone, Henry P. McIlhenny, Katrina Van Hook, Elizabeth Dow, Charles C. Cunningham, Professor Edward W. Forbes, Mr. Depinna, John Murray.

They visited the collection of the Widener family at Lynnewood Hall outside Philadelphia, where the entire class of twenty-eight was given lunch and waited on by footmen in livery. They were served tea at Grenville Winthrop’s townhouse in New York City, where they viewed his unrivaled collection of nineteenth-century French paintings and sixth-century Chinese sculptures and jades. Sachs assured his students that the collector would be more than happy to tell them how he came upon this jade or that picture. “Look around,” Sachs would say. “Ask any questions you like.”25 They were welcomed at Abby Rockefeller’s townhouse on West Fifty-Fourth Street, the first home of the Museum of Modern Art. They called on Joseph Duveen, the premier dealer in old master pictures, at his stone palace at the corner of Fifty-Sixth and Fifth. Duveen would appear in his morning coat, surrounded by his faithful assistants. “The great Lord Duveen would crack a few jokes and show us a few treasures,”26 remembered Rathbone, and he could easily see the magic this dealer worked on his wealthy clients, especially the legendary superrich of the older generation such as Frick, Morgan, Widener, and Huntington. In Washington they were personally welcomed by the curators of the National Gallery and of Dumbarton Oaks, and the collectors Duncan and Marjorie Phillips. These were the kind of receptions Paul Sachs had come to expect – and his students to enjoy – from the extensive network he had developed over decades.

A scholar may work in solitude, but a museum professional needs to be out working in the world, and Sachs never ceased to stress the importance of personal contacts. He shared his long list of leading art world figures with his students, including his careful instructions on how European nobility should be addressed, as in “My dear Contesse Beausillon” or “My dear Lord Crawford.” While it was easy to recognize the great collectors, Sachs also taught them to never condescend to the lesser known, never to “high-hat”27 the amateur, for they might very well know more than you assume, and their resources and potential for support were inestimable.

Likewise Sachs told his students to become familiar with their trustees and to visit them in their own homes. Equally important, it was essential to know how to entertain them. When an important out-of-town visitor came to Cambridge, Sachs hosted black-tie dinners at Shady Hill, inviting his students to these lavish affairs to show them both how to dress properly and how to create the right atmosphere for cultivating the rich. Last but not least, he encouraged them to become collectors themselves at whatever level they could afford. Rathbone’s classmate Henry McIlhenny, coming from a family of considerable means in Philadelphia, had already purchased a major still life by Chardin, which he hung over the fireplace in his suite at Dunster House. Rathbone’s budget could accommodate only the odd Japanese block print to be found in secondhand bookshops, but those thrilled him just as much. It was not until his senior year that he acquired his first oil painting – a primitive American portrait of a dark-haired gentleman dressed in black. For this stern Yankee – later attributed to Sheldon Peck and today valued at five thousand times what he bought it for in 1932 – he paid five dollars to a roadside antique dealer in upstate New York.

Sachs embraced his students as if they were his own children. As in any family there were inevitably some children who were easier to manage than others. It was difficult for Sachs to assert his superiority over the three students who had started the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art – Kirstein, Warburg, and Walker – partly because they belonged to the same close-knit New York (and largely Jewish) society that Sachs did. Warburg considered Sachs “a humorless little cannonball of energy,”28 Walker called him a “stocky, strutting little man,”29 and Kirstein said he was “a small and nervous man, who hated being a Jew.”30 Some considered Sachs a reverse snob and observed that he tended to favor students not as privileged as he was. This made for a naturally congenial relationship between Sachs and Perry Rathbone – who was neither privileged nor Jewish – that lasted well into Sachs’s retirement. “If he liked you, he would never desert you”31 was the impression he made on Rathbone, and this proved to be true, far beyond the course of his Harvard years. Sachs wrote letters of recommendation for Rathbone at the drop of a hat, letters that were the gold standard in the field. This opened many doors as he made his way west after Harvard in search of a professional life, landing his first job in the depths of the Depression at the Detroit Institute of Arts under its legendary director William Valentiner. When Rathbone eventually returned to Boston in 1955 to take over the MFA, Sachs was there to greet him and to counsel him.

By World War II Sachs had trained hundreds of young men and women as museum professionals. He had, almost single-handedly, created a nationwide network of the ruling elite. This network would continue to work together for years to come, trading opinions and personnel, collaborating on loan exhibitions, and meeting annually at the American Association of Art Museum Directors, an invaluable sharing of experience and ideas, for which Rathbone served as president for two years. The museum course was the bedrock of Rathbone’s approach to museum problems and leadership as he set out into the real world, along with his museum course classmates James Plaut, Charles Cunningham, Henry McIlhenny, Thomas Howe, and Otto Wittmann. All would go on to play leading roles in the American museum world. Together these men would create a fraternity of professionals sharing the same high standards of museum management they learned from Sachs at Harvard. By the mid-1960s they had come of age, and so had their achievements.

But Sachs could take Perry Rathbone only so far. Now he was about to enter the wilderness without a map. For it was not only the social and urban landscapes that were changing but the American museum as well. The problems Rathbone faced were in large part those of the monster he and his colleagues had helped to create – a much larger and more diverse audience, with much higher expectations, a public hungry for blockbuster exhibitions and ambitious building programs. By the 1960s these pressures had reached a new peak, and it was during this same restless period of change that Harvard’s Museum course was finally dissolved.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Huntington Avenue façade, 1920.