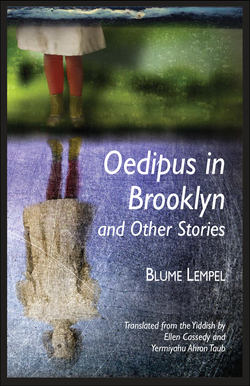

Читать книгу Oedipus in Brooklyn and Other Stories - Blume Lempel - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIMAGES ON A BLANK CANVAS

Through the sun-drenched streets of Tel Aviv I follow the coffin carrying my girlhood friend Zosye to her eternal rest. Inside my head, black crows caw loudly around the dead body, blocking the streets and the passersby and the hearse at the head of the procession. Their din prevents me from gaining access to the ways and byways that led Zosye into prostitution.

It is my first visit to Israel. Intending to go to Eilat, I had already checked out of my room in Tel Aviv and packed my toothbrush when the head of our immigrant society called to invite me to the funeral. I have long since learned to skip over the place where my cradle once stood and instead to seek my origins in the stony strata of history — to search for the living source under the sands of the Negev, shadowed by time, to sail through the gates of the desert and steer my ship along its fated course.

I have placed a film of artificial frost over the small window that looks back into my past. There, white trees and dead roses are always in bloom, not as a memorial, but as a reminder that the layer of ice is an illusion, nothing but the thinnest skin stretched over black depths where snakes and scorpions feed on the remains of their unburied victims.

Whenever I encounter someone who has escaped from the abyss, I look at him with terror, expecting to discover something that disturbs my sense of how things are.

As I ride along in the car, my eye follows the carriage carrying Zosye’s martyred bones. I seem to hear the letters “s” and “z” dangerously sharp in her Polish name. Zosye, Zoshke, the bookkeeper’s pampered daughter, is riding her bicycle, her windblown hair as blond as the furniture in her father’s parlor. When Zosye laughs, the rows of trees lining the road respond with an emphatic “yes!”

Many girls in our small town spoke Polish, but Zosye’s Polish had deep roots. Absorbed with the milk of her gentile wet nurse, it was a mark of her dual identity.

I leaf through the pages fluttering in my mind. The black crows retreat into the background. The open path ahead leads to the town where I grew up. I follow the town princess to the shadowy corners of the world, and to the sea, to the blue shores of the Mediterranean into which she threw herself. I don’t see her the way she looks now. Sealed in the coffin, she is safe from curious eyes. She is no longer for sale, neither to earn money nor out of despair. Against her will she arrived in this world, and against her will she has departed.

Three other people are sharing the car with me. They, too, are shuffling through pages — pages marked with judgments. “She was a streetwalker who lived with an Arab.” They exchange information they have observed with their own eyes. I am trying to see the invisible. I don’t trust the eye that relies on facts. Half-truths can mislead, divert the guilt from murderer to murdered. The corpse is silent, and the murderer, protected by the privileged status accorded him as a citizen, a father, and perhaps by now a grandfather, sips his beer in peace and grows fatter by the day.

“Why didn’t she adapt to the new way of life? Why didn’t she become a productive member of society like other immigrants?”

I don’t answer these questions. The truth is concealed beneath bloody bandages; the painful wound may not be touched. It is clear that a single standard does not fit all. I believe no suicide is an accident. Every hour, every moment, the suicide holds the blade over her throat. Zosye committed her first suicide — her initial, spiritual suicide — in Felix’s attic. The physical one came gradually, step by step.

I meander along the victim’s own paths. I know who murdered her. In exchange for a piece of bread and a slice of ham, he sated himself on her blooming, sun-ripened white body. Perhaps she committed suicide even earlier. Perhaps her life ended on the wild autumn night when Felix arrived like a prince on a white horse, bearing a loaf of bread and a peasant skirt, blouse, and kerchief. Zosye donned the clothes and kissed her mother’s wet face, black as that autumn night. . . . She kissed the dog that lay by the door without understanding that the house he was guarding had become a prison. She kissed her father’s body, which had lain abandoned in the marketplace after he was shot. She kissed the piano and the garden that surrounded the house. Everything, everything she gathered up inside her, hiding it like a ransom in the cellars of her being.

Behind Felix’s barn, downhill from the path, stood a pond bordered by linden trees. Beneath its slimy green surface, fish were spawning. On sunny days Zosye could see them swimming in the water. She could see the black rings on the green-mirrored surface. Through the narrow crevices in the attic, these rings became the only outlet for her famished gaze. Looking down, she would imagine the ring she’d create when she threw herself into the water. Buried deep in the hay, she had time to mourn her own death and to attend her own funeral.

Now, on the way to her funeral, I want to tell her that I see with her eyes, feel with her senses. I picture perspiring beds. I caress bodies with her fingers. I do it in the spirit of the girl I once knew, searching for a sign of today in the buried world of yesterday. In that light, or more aptly put, in those shadows, I seek to glimpse the why and the wherefore. In my mind I lower myself into the abyss, following the overgrown footpath to long-ago.

Sometimes in those days, after I’d brought my father his coffee in the butcher shop, I would stop at Zosye’s exquisite garden on my way home. Standing on tiptoe, I’d peer over the fence and marvel at the golden lilies that grew around her house. I would bemoan all that could have been but never was. If my grandfather hadn’t been so stubborn, if he’d yielded to the demands of Zosye’s father’s parents and provided them with the dowry they asked for, then I, not she, would have been the bookkeeper’s daughter, playing the piano and preparing to travel all the way to Lemberg for my studies. But my pious grandfather was loath to go against his deeply-held ethical beliefs by making a promise he knew he could not keep, and so the bookkeeper and my mother had parted forever. He married a rich man’s daughter, and my mother married a butcher boy.

I used to stand at the fence and imagine how it would have been, if only. . . .

Today, as a tourist from Paris, I accompany the bookkeeper’s daughter to her eternal rest and remember how gladly I would have relinquished all my worldly ambitions to study in Lemberg.

Through the skylight of my Parisian garret I used to look up at the tiny rectangle of heaven that fortune had allotted me and conjure up Zosye’s lush, slumbering garden. How I cursed the fate that had stranded me in Paris on my way to Israel!

Zosye did not want to go to Israel, nor did she need to. For her, the vine was abloom with all the brilliant hues of the bejeweled peacock that resides in the dreams of every young woman.

How could she have known, as she played the piano, that the civilization of those magical notes was even then writing her people’s death sentence? How could she have known that form and harmony were but the seductive song of the Lorelei, the façade behind which the cannibal sharpened his crooked teeth? Protected and sheltered like the golden lilies in her father’s garden, Zosye could not see those teeth. With the natural power that is the birthright of every living thing, she glowed in the light of the sun. Endowed with all the attributes she needed to thrive and grow, Zosye was primed to scatter her own seeds across God’s willing earth.

The pages I turn are blank, as unreadable as the image in a shattered mirror. It occurs to me that the earth to which Zosye is now returning holds the remains of another prostitute, the biblical Tamar, who sat down at the crossroads where fortunes were decided and seduced men with her charms. I search for a spark of Tamar’s desire in the image of Zosye that is anchored deep in my memory. I search for the lust of a whore in her dimples and her rosy, Polish-speaking lips that surely didn’t even know the meaning of the word “prostitute.” I look into her eyes, the reflection of her soul. Her character, unripe, uprooted, is borne by the wind to the four corners of the world. I search for the legacy of modesty passed down through the generations. I search for the set path of her father, and before me another form rises up: her Uncle Shloyme, the Russian. I don’t force this figure to take shape — I let it grow on its own. I relive the terror that his death caused me, which penetrated my dreams long after I’d left my town behind. His imposing figure rises out of the mist: gray eyes, bushy black eyebrows, broad shoulders, erect and proud. From his mouth I heard for the first time that “all is vanity.” When Shloyme spoke, every word burned, a reflection of the grief and rage that gradually devoured him. At the time I imagined he looked the way Job did when he sat down in dust and ashes, despising himself. “What is the difference between man and beast,” Shloyme asked, “if even a rabbi will paw at his wife’s tits?”

These particular words, expressed at our home one Sabbath afternoon, provoked a radical shift in my thinking. I too began to ask questions that led me off the beaten path. When Shloyme the Russian lay on his death bed, he wanted only one thing: that God should grant him sufficient strength to get out of bed, set the house on fire, and be burned with all his worldly possessions on God’s eternal sacrificial altar. And, in fact, this is what he did. People said that years earlier he had been banished from the Jewish community for reading the heretic Spinoza and for walking too far outside the town limits on the Sabbath, in violation of Jewish law.

Did Zosye, too, search for a path to God through alien gardens? Did the tragic worm that consumed Shloyme the Russian make itself at home in her soul and force her to leave the main road and set off on another? Did it force her to walk beyond the Pale and excommunicate herself?

Shloyme the Russian had a legitimate claim against his Creator. His barren wife turned away from the Almighty before he did. She became devoted to black magic, ghosts and spirits, and witches who fed her wild herbs and swindled away a fortune with promises that help would come her way if she followed their directions. And so Shorke the Russian, Shloyme’s wife, did as instructed. She strung around her neck the claws of a crow and placed the hairs of a she-panther in her bosom. At midnight she bathed in the milk of a pregnant cow and outlined her navel with the blood of a bull. Her hair unkempt, eyes painted with soot, cheeks rouged with chicory paper, Shorke approached her husband to be fertilized.

In the car all is quiet. I look out onto the winding streets of Jaffa. The sky is a pure, light blue, without a cloud to anchor the mind. The hearse carrying the corpse continues ahead. Parallels multiply; characters who have no obvious connection to one another become entangled like roots under the earth. They worm their way into the core of Zosye’s being. They help me to construct a woman from the child of long ago.

I see the woman in Felix’s attic. She is speaking to God, pleading with Him to spare her mother and her little sister. She pleads until there is nothing left to plead for. The city has been destroyed. The past is no more. Perhaps it never was? The abyss she is looking into has lost all familiar markers. No signs of yesterday, no indications of tomorrow. The forest in its innocence is in full flower. Fish multiply in the pond. Cicadas call to one another; male and female come together in the deep grasses of the meadow. Zosye knows she is pregnant. The cow in its stall is pregnant, too. Both are silent. The cow chews its cud and ruminates. Zosye picks up a stalk of straw and does the same. She thinks mostly about eating. Not about the wild strawberries with sweet cream that her mother used to serve, but about bread with salt, perhaps with a clove of garlic.

The chickens in the courtyard peck at their grain and carry on with their squabbles. They have no idea that man has confined them in a ghetto for his own gain, that cold, cynical human calculation has lodged them in a comfortable death camp. Whenever he feels like it, he’ll grab a cleaver and chop off the white head of a hen, whistling all the while. Zosye is not afraid of death. She accepts Felix’s favors like the cicadas in the grass. She doesn’t tell him about the pregnancy.

Felix has a wife and children. He keeps Zosye in his mother’s attic, holding his mother responsible for her safety. Felix’s mother is well aware of her son’s desires and knows that he means what he says. She makes sure not to let the Jewess out of the attic. She hides Zosye’s food in the bucket of oats for the cow. Felix’s mother is talkative. She prattles on at length about how the Germans have shot all the Jews, stacked the corpses like timber, doused them with kerosene and set them ablaze. She doesn’t conceal her satisfaction. She hates the Germans, but their savage treatment of the Jews is pleasing to her. “It’s high time we were rid of them,” she says.

Zosye doesn’t tell Felix about his mother’s chatter. She has long since stopped complaining, either to God or to people. She lies in the attic and listens as the front draws closer every day. The stable trembles with the heavy shelling that rolls like spring thunder. Zosye does not wait for tomorrow or hold onto today. Now that liberation is near, she wants only to sleep. In her dreams she has a past. She has a father, a mother, a clearly demarcated path, a straight line between two mountains of snow. She glides on ice skates; diamonds sparkle in the sun. Overwhelmed with bliss, she closes her eyes just for a moment — then loses her way in a fierce blizzard.

Zosye sleeps. She wants to gorge on the dream until she chokes. But when the liberator bangs on the door, she can’t find the strength to get up and open it. Instead, she lies there, listening to the cells dividing in her bloodstream. She takes her pulse and counts her heartbeats. She descends deeper and deeper into the black shafts of consciousness. Inch by inch Zosye draws back into herself. The footsteps of the liberator echo rhythmically on the road. She has no road. Her paths are overgrown with grass. She digs into the earth, under the weeds, touches the root with its suicidal poison — then gets up and climbs out of the attic. She pauses next to the cow. For a long time they stare at each other in mute understanding.

Slowly and carefully, Zosye walks down the hill between newly planted garden beds. She goes to the pond covered with green slime, closes her eyes, and throws herself in.

Zosye opens her eyes in the hospital. A bit of congealed blood trembles in a glass by the side of her bed. “A four-month-old soul,” says the nurse. “Everything inside you was rotten. It all had to be removed.”

Zosye smiles and says nothing. She asks no questions; she has no wish to know. Perhaps she thinks about her aunt, the barren Shorke? The truth is she is utterly indifferent. She lies in bed until she’s ordered to leave. Along with other wind-blown wanderers, she roams from camp to camp. But even here she’s alone. Zosye tries to go with the current. But the severed branches, leaves, and stones carried by the flow get in her way, piling their dead weight on her young shoulders. They paralyze her will, cutting her off from the stream of history and pulling her down into the abyss.

Sometimes, when Felix was tormenting her, the tears would come like a benign rain. He was the rod of punishment whose blows she endured for the sin of abandoning her mother and sister to their deaths. Each bite of bread she paid for with self-torment and selfhatred. The same feeling of guilt followed her to Israel.

At war with herself and with a reality to which she could not adjust, Zosye searched for meaning and found it in self-abasement. The deeper she sank into the swamp, the more entitled she felt to walk on God’s earth.

Zosye lay on the bottom and allowed herself to waste away. Like the Greek god Prometheus, bound to a rock, his insides gouged by an eagle, she stood with her belly exposed to the predatory birds of the world. And when the birds of prey had nothing left to peck at, she went to the sea, just as she had once gone to the pond, and threw herself in.

Enveloped in silence, I sit alone in the car. I, too, am avoiding reality. In the distance her grave is being covered. A man with a long beard and a broad-brimmed hat is reciting a prayer. I see that he’s hurrying. Soon he’ll recite the same prayer at another grave. I don’t need to hear what he’s saying. Instead I listen to the prayer that trembles inside me, a prayer that can never be repeated. It is a prayer without words, a prayer buried deep in the collective consciousness of my people. The man with the beard rushes on. Somewhere another corpse awaits him. The prayer I recite has no end. It seethes and bubbles like a chemical brew on the brink of existing. In the mixture I look for the symbol that Zosye lost. I must find it and clean off the mud, the impurity, the shame.

I know I will return, perhaps tomorrow, perhaps a year from now. Using the new-found symbol, I will erect a tombstone, a blank stone without words. The passerby who stops will have to create Zosye’s image from what is not stated. He’ll stand before the stone like a master before a blank canvas. Among all the images that leap into his mind, he will need to see first of all that Zosye is the crow that pecks at my conscience.