Читать книгу Human Happiness - Brian Fawcett - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеApril 1945

ONCE UPON A TIME, we were an ideal family. There were six of us: an industrious mother with a quick smile; a serious, hard-working father; twin girls; two younger boys, one—me—an infant. There were no health problems in this family, not a disability or cognitive delay reared its head, no troubling or unruly behaviours in the children were noted, and the parents had no debilitating vices or unattractive quirks. There was a tiny mortgage on the small home my father built by himself in a pleasant neighbourhood, there were mountains and rivers without end for the kids to roam through, and not a drop of non-British blood in our ancestry was admitted to—not that we cared who our ancestors were.

We were the kind of family that Canada’s armed forces had just fought the Nazis and the Japanese to preserve, God Save the King. Now the war was ending, and the world, despite its convulsions, seemed as bright and filled with hope as at any point in human history. Penicillin had recently arrived to save us from bacteria, DDT would save us from disease-spreading crop-eating bugs; people like us knew nothing about the Holocaust, Hitler would be dead in a few weeks, Uncle Joe was still our friend, officially, anyway. The atomic bomb was still a few months in the future and we had no notion that the Cold War and the Communist Menace were being cooked up in the minds of American politicians and their military planners. An end to 30 years of misery and killing and maybe a beneficent World Government was what ordinary people could see on the horizon in April 1945.

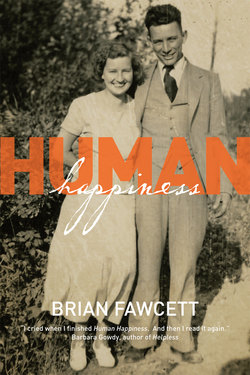

It was a good time to be alive, and my parents knew it. There had been no war deaths in our extended family this time, and my father had the same secure job that had kept him from conscription. The photographs taken of us at the time show us clear-eyed, confident, and attractive: father in a business suit, mother in a comfortably fashionable housedress, and the four children dressed in clothes my mother had made herself. Each one of us gazes at the camera as if the world was someday going to belong to us. Picture-perfect; ideal.

But ideal, like picture-perfect, can be a long way from perfection. Even the picture, examined more closely, reveals some flaws. We are posed on the whitewashed porch of the white clapboard house my father had just built. The porch, if you look, needs several more coats of whitewash, and you can’t see that the house behind us is cold in winter because the sawdust that fills its walls for insulation is already settling. The part of the world we inhabit has a few flaws, too: a small dirty frontier town called Prince George, B.C., set at the confluence of the blue Nechako and muddy Fraser rivers, and surrounded by limitless forests of pine and spruce trees at the then-northern limit of settled Canada. We are isolated from our extended families and most of the amenities bigger cities offered in those days. The northern winters are very cold and snow-filled, the roads uncertain most of the year—or non-existent—and food, although plentiful enough, is sharply limited in variety due to the transport distances.

To my parents, Hartley Fawcett and Rita Surry, these less-than-perfect things are acceptable trade-offs for the freedoms they gain by living on the frontier. My father is free of his destiny, that of a subsistence grain farmer, and my mother is free of her own troubled family. They can look to the future, which they believe will be perfect. My father, always an optimist, believes that Prince George will be populated with a million people by the twenty-first century, and he has nearly a million plans to get his share of the wealth all that growth and progress is going to bring. My mother likes the town, too, but for different reasons. “I knew from the first moment,” she will tell me years later, “that this would be a safe place to raise my children.”

This is as good a place as any to warn you that this book is a memoir, and that, even though I wasn’t a particularly loyal or attentive son to my parents, I have a familial as well as authorial stake in it. I’m very much aware of what the incendiary American cultural critic David Shields recently wrote: “We remember what suits us, and there’s almost no limit to what we can forget. Only those who keep faithful diaries will know what they were doing at this time, on this day, a year ago. The rest of us recall only the most intense moments, and even these tend to have been mythologized by repetition into well-wrought chapters in the story of our lives. To this extent, memoirs really can claim to be modern novels, all the way down to the presence of an unreliable narrator.”

It happens that I have a fairly odd sort of memory, insofar as I seem to go quite far out of my way to not remember the intense moments that families tend to mythologize. What I do have recall on, and with an unsettling degree of clarity, are the moments of physical slapstick that are part of everyone’s life, and usually a suppressed part. I inherited both my mother’s bullshit detector, which was the most extraordinary piece of equipment life conferred on her, and my father’s inability to suffer fools quietly even when I’m the fool. I also have, thanks to modern digital photography, an unusually large collection of family photographs, along with a trick that has helped me to penetrate their surfaces: I enlarge them to 8 1/2 x 11, which lets me peruse them at a level of detail not previously available. You saw one small result a moment ago when I pointed out the poor whitewash job on the steps in the 1945 family portrait. And at the risk of seeming immodest, I am a skilled researcher, and an obsessive amateur detective. Finally, I am hyper-aware of the dangers of what I’m doing, and not, in the normal course of things, prone to getting washed overboard by sentimentality.

What I’m trying to figure out here, as the title of the book suggests, is what human happiness is about, and what it tells us. I’m examining it through the lens of the happiness my parents felt at being in the world. I want to discover what specific cultural or personal tools they used to build and maintain it, and where that tool box went. Because the tool box has vanished, and what makes human beings happy has changed.

When Hartley Fawcett and Rita Surry were young, happiness was a noble pursuit, one that, in their minds, led without ambivalence to “the Good Life.” But somewhere in the last half century, “the Good Life” has lost its definite article. Today, one can only lead a good life, and that has become an ideological, censorious, and antihumanist term, one that can be experienced only individually. Not sure what I’m talking about?

Try to imagine a group of people gathering on a contemporary North American or European civic space to celebrate the joys and achievements of humanity. First of all, it isn’t going to happen. If it did, it would draw a hostile counter-demonstration: animal rights activists who’d argue that we’re mistreating every other species; environmentalists, most of whom see human beings as a terrible scourge on everything else on the planet, would join in, followed by anti-racists hollering that all this fun is coming at the expense of the underdeveloped nations and people of colour, wherever they’re living; supporters of NGOs dedicated to wiping out disease and poverty in the underdeveloped world would join in, bickering at the celebrants for not doing enough, not doing more.

I remember my mother, while I was very young, excusing the weakness of a family friend by saying, well, she’s only human. It was a forgiving, affectionate explanation, and I recognized that at its root was the idea that to be only human was an essentially good thing. I was comforted by the thought that I too was only human.

But somewhere along the line, that comfort has vanished. To be “only human” in the twenty-first century is to be merely human, an aggressive and distasteful condition. It means being disconnected from nature’s laws, it means being selfishly venal, and probably destructive: an alien force, hostile to the well-being of the planet, at the bottom of the hierarchy of goodness.

How did we get to this? I and my children may end up leading good lives, but we have no shot at the Good Life the way my parents understood it because our joy and comfort at being what we are comes at the expense of one of a thousand disadvantaged minorities or will contribute to the further impoverishment of fragile landscapes and ecosystems, will endanger every threatened animal or plant, and will further pollute the planet. I can live with this because I’m used to it. But my kids have lost their right to collective human happiness because it is too costly to the planet and to the rest of their fellow human beings. That bothers me. It leaves them to lead guilty lives, with pleasures that are deemed anti-social and selfish.

Something else. The empirical observer in me has noticed that most people today think about happiness the same way art critics see still life painting: as a fixed state in which a nexus of static objects supposedly sheds an aura of light and exactness that evokes a summarizing kind of external meaning, usually in the form of a slogan. Life Is Short; Life Is Beautiful; Pleasure Is Fleeting; Don’t Worry, Be Happy.

At its core, still life is a distortion. If it were language, it would make sentences in which there are only nouns, with a halo of sepia where the verbs ought to be. Inside that sepia, however, rests the creator’s slogan, along with whatever prejudices he or she may have about the world. In art, and sometimes in life, there are formal intentions which take the form of a prescriptive syntax. For instance, some of the objects in a still life must be of human fabrication, some must be harvested from the world. In a typical still life, you might find a dead pheasant resting beside a rotting pear lying in front of an old bottle, while across the pheasant’s breast lies a slightly rusted knife.

The contemplation of still life constructions comforts people, but I don’t believe them for a moment. There is no such thing as still life, not really. Life is never still. The pear will soon rot or be eaten, the dead pheasant must be plucked and put into a hot oven before the maggots take over, the bottle recycled in a blue box or filled with gasoline and stuffed with a rag to make a Molotov cocktail. Don’t ask about the knife. And then there’s the real world, the one most of us live in day by day trying to find happiness—or a car dealership that gives away BMWs.

Happiness is subject to the same logic as still life: in the real world, if happiness and/or still life or even the Good Life exists, it is only for a moment, and glimpsed in flight. Things must move along in the real world, and every attempt to control or stop the movement fuels the slapstick that breaks it down into the human condition: moments after the painter sets his (or her) arrangement, his spouse (or one-eyed hunchbacked assistant) trips over a bucket of apples or empty Pepsi cans and scatters the arrangement. The bottle smashes on the floor, the family dog grabs the pheasant and runs for the door, trailed by the screeching spouse and followed, at a more leisurely pace, by the painter, who has a slight smile because he (or she) understands the artifice of the still life arrangement and the ease of making another construction—or maybe there is a lover waiting a few blocks away, and this accident will hasten the end of the working day.

Real world happiness isn’t, as the pie-faced optimists of Oprah Winfrey’s reality have it, an arrangement of self-inflating, easily faked pieties and on-camera revelations. It is intangible and limited, a fleetingly experienced emotional evanescence lodged within a continuum of other, not-necessarily-sanguine events. Except for a few very underemployed, self-involved, or very lucky people, happiness isn’t an accomplishment one gets to flash like a police badge or a designer handbag. It moves and shifts within the currents of everything else, always elusive, rarely surfacing in the same way or in the same figuration. Without effort, attitude, and concentration you don’t even know that it’s there, and even if you do, you’re more likely to trip over it and fall down the stairs than to find the time to clasp it to your spiritual bosom and genuflect over it.

But wait! The photograph of my family, taken in April 1945, rebukes this. The postures and characters you see in it—and the strain of happiness it self-consciously attempts to represent— remained still and stable until the twenty-first century, more or less. On the left is my sister Serena, named by my father before he knew he had twins, and given the name for her demeanour at birth. He holds her, not quite closely, both of them gazing at the camera as if the eye of the future was upon them. Behind him my brother, Ron, stands, a little shy, but proud to be at his father’s shoulder. I’m on my mother’s knee, chubby and imperious, the little prince on his throne. My mother’s smile is like my brother’s, shy but determined all the same. On my mother’s left is Nina, Serena’s older-by-a-half-hour twin, not serene at all. She is coiled and impish; full of light. Ideal, picture-perfect happiness.

It took my mother’s death to shake us from these ideal stances. By then, we were anything but picture-perfect.