Читать книгу Human Happiness - Brian Fawcett - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеWild Strawberries

HARTLEY FAWCETT fervently believed that he was a self-created man, and Rita Surry, just as passionately if not as loudly, molded herself and her life as the exception to every rule by which her family lived—or, in her view, ran amok. That made them both, like their own parents and immediate ancestors and unlike their siblings, pioneers. Pioneers are unrooted people, interested in acquiring property, making money, and building large families as a protection against old age and contingency. They are contemptuous of the past, oblivious to most cultural and historical nuance and indifferent toward anything other than practical understanding.

But my parents were a different sort of pioneer: less constrained by subsistence, and the frontier they sought was as much psychological as it was physical. They wanted to get ahead of other people, build solid material foundations for the future, and, most important of all, do things differently than their parents and siblings.

Pioneers are different from immigrants. My wife’s Eastern European parents, although born in North America, are typical of immigrants in that they are most interested in family and ethnic solidarity, educating their children and gaining social prestige. They have been obsessed by questions of obligation and social responsibility that held little interest for either of my parents.

Me? I’m Canadian, which is different again. I have a sensibility that includes elements of both pioneer and immigrant values, but has been shaped by the multicultural society around me. I’m trying hard, for instance, to infect my children with a sense of their genetic and social connectedness to both the people around them and to their ancestors, and I’d like them to have a deeper appreciation of the complexity of the present and past than I was brought up to observe. But like my parents before me, I have no ethnic chauvinisms, and I have their determination to do things my own way, their eye for practicalities, and I have their skeptical view of social convention: if everyone is doing it, that is cause for wariness.

Put another way, I want my children to understand the specific flavour of wild strawberries and I want them to know where to look for them. I want them to know how wild strawberries differ from the genetically modified and tasteless agribusiness strains, and in which ways—and when—the flavour of the local strawberries in season still resembles the wild ones.

Being Canadian this way, and with an almost infinitely better access to the specifics of the past provided by an information-enriched world, has convinced me that the people who raised me weren’t entirely self-created. Like most people, their family histories reveal more than a few things they couldn’t—or wouldn’t— have: the contrariness of their characters, why they got so far from home and from their families and the comforts offered. That’s why I’ve located the family closet, and have pried open its door. Out pour the skeletons—and the wild strawberries.

The wild strawberries I’ll pick and try to present with their flavour intact. The skeletons are another matter: they explain too many of the whys and whats to leave out, but they’re not the story, which is about two people who deliberately stepped outside the slow-moving continuums of history and genetics that made them. Thus, I’ve forced the skeletons back into the closet, and I’ve parked the closet at the end of the book, for the edification of those who want to open it.

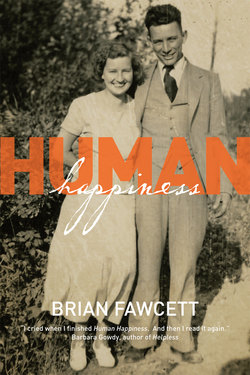

How my parents first met isn’t a story that has survived in the form of a singular thrilling anecdote. Hartley Fawcett worked on the trucks for a meat-packing company and Rita Surry worked at the Hudson’s Bay Company, the largest meat and grocery outlet in Edmonton at the time, so it seems logical to suppose that she met him that way.

But maybe not. My mother once told me a wistful story about my father appearing at one of the dances she organized with her girlfriends. He’d been the date of an acquaintance, and she herself was there with a police constable she didn’t much fancy. She spotted my father the moment he walked in, and said that he spent the evening glancing at her. He was slim, handsome, and strongly built, with bright hazel eyes and a shock of jet-black hair. She said he had a reputation for wildness, but quickly added that what mattered to her was that he was a man with strength and ambition, and that his wildness could be tamed.

“He was a catch,” she said, ruefully. “But when you’re in love, you can’t really be sure of exactly what kind of fish you’re catching.”

Fred Surry, my mother’s father, ran across my father well before she did. Hartley Fawcett had shown up at the taxi stand next door to Fred’s book and coin shop to collect whatever he could of the thousand dollars he’d lent to one of the taxi owners, a burly pipe smoker in his late thirties. When the cabbie didn’t have the money he owed and showed no inclination to get and give it up, an argument ensued. Fred Surry heard the commotion, and arrived too late to catch the taxi owner taking the first swing at my father. But he was perfectly timed to see my father counter with a punch that put the larger man’s pipe through the side of his left cheek—and to then watch my father stand over him as he bled and threaten to do worse if he didn’t pay up, and soon.

The impression Fred Surry got from the incident was almost as inaccurate as it was dramatic. Hartley Fawcett was no thug and he wasn’t one to start fights. He just ended them, usually with a punch-line. What Fred had seen was a young man convinced of his cause— the latter trait would be a lifelong constant—and a counter-puncher able to back up his cause with a boxer’s right hand and a mouth to match.

That first impression was the only one Fred Surry was willing to entertain, and my father did nothing to alter it. When Fred found out his daughter was dating him, he tried to stop it, cornering my father when he brought her home at midnight from their first date.

“Just what do you think you’ve been doing with my daughter until this time of night?” he screeched.

“Out chasing chickens,” my father snapped back, likely sensing that he was doomed no matter what he said. “Be thankful I’ve brought her home at all.”

My mother kept dating him over her father’s objections. It isn’t clear if he kept her out all night before they were married, but there were tales about motorcycle rambles deep into the Alberta countryside, and others about sleeping in haystacks. There’s also a rumour that the two of them rode his big motorcycle to Vancouver and back. That hints at many things, not the least of which is that my mother’s youthful stamina and her zest for adventure weren’t so dif ferent from my father’s. In the early 1930s, Vancouver to Edmonton was a round trip of almost 3000 kilometres, and over roads too stony and bad to even think about.

When my parents married in August 1936, Fred Surry refused to attend the ceremony. He forbade my grandmother to go, too, but she went anyway, to hell with you. After that, he refused to be in the same room with his son-in-law and went so far as to disinherit my mother in a 1937 revision of his will. He called my father “the Indian”—it was unclear if he was referring to the motorcycle or his dark good looks—and predicted future moral and financial doom for his eldest daughter.

There’s no question that my parents were in love when they married, but there was a calculated element on both sides. It’s clear that to my father, Rita Surry was a “catch”: she was pretty if not quite beautiful; she was sensible and practical, and very organized and focused. She was better educated than he was, more cultured, and more socially adept. For her, he was a project, and of course, also a “catch”: handsome, strong, and ambitious, a man with the sort of inner drive that she sensed could be molded. My mother didn’t stray far from her common sense, even in matters of love. Romance was one thing, but as the saying goes, you gotta have something in the bank, Frank. She did not want to be poor the way her parents had been, and my father promised her that one day, she would ride in Cadillacs.

So there was romance, and love, and there was marriage, and the future, on which and in which they would work together. That was the deal; that was the ground of their love for one another.

Now, I believe that all marriages begin with a fund of goodwill that, once spent, is difficult to regenerate. If there is too much inattention or lying or if there is infidelity in a marriage, it devours a portion of the goodwill that can’t be regenerated. The marriage might survive—less frequently today than in past generations—but it will do so with reduced passion, and commensurately decreased trust.

As husbands go, my father had strong virtues. He was financially responsible, he didn’t drink or gamble or hang out with the guys unless it was business, and he didn’t chase around, come home late or not at all. He was a man focused on financial security and on business success, he saved money, and was unusually competent at the things husbands of his era needed to be good at: he could bang boards together, fix anything around the house, and he was a genius with mechanical devices. What more could a wife ask for?

Quite a lot. By nature, my father wasn’t a physically affectionate man, although he seems to have tried to be during the first years of the marriage. According to my mother, he was a clumsy and inattentive lover who grew less attentive as he got older. He also carried never-to-be-examined beliefs that men were superior to their women and that he had to be the boss. Even in the last months of his long life, he still hadn’t wavered on either.

In the 1930s and 1940s his shortcomings were hardly villainous, and they certainly weren’t unusual. But to my mother, they caused frustrations, irritations, disappointments that chipped away at both her self-respect and her affection for him. But she had settled on my father as well as settled for him, and that was not something that ever really occurred to her to reconsider. Yet she wanted a good marriage, and that meant good in the less tangible ways too: she believed, well before its time, that sexual happiness was her right. And so, subtly and unconsciously as the goodwill between them began to dissipate, she turned away from him, shifting her focus to her children, and my father’s focus shifted to business—getting her that Cadillac he’d promised her.

Understanding my father’s perspective is more difficult because he was, as most men are, less articulate about what he wanted from his wife and from marriage. I think he got most of what he wanted: a competent homemaker, a healthy mother for his children, one who cared for them as they grew up. In my mother he also got a couple of bonuses he likely found useful without being able to admit it. He got a wife with the social graces he lacked, and one with a better head for figures than he possessed. She kept the family books until she was in her mid-eighties, and during the 1950s when his business was touch-and-go, she kept her finger atop the accounts.

But what didn’t he get? I can hear my mother’s snorted answer: “Someone who’d take his bloody orders without questioning them. And it’s a good thing I didn’t take his orders. He’d have put us in the poorhouse several times with his stupid schemes.”

That’s not wrong, but it isn’t complete. He didn’t get much sweet goodwill from my mother, either, not that he’d earned it. And so he lived without it, just as she did. The marriage went on, always a functioning partnership, but it was not the stuff of sweet dreams. My mother rode in the Cadillac, eventually. But she never once got to drive the damned thing. Not even after she’d had a driver’s licence for 40 years.

And so the years begin to pass. My father quits his safe job, buys his business and begins to work 14 hours a day. My sisters grow into teenagers, get pregnant and are both married by 18, my older brother buys his first car and I don’t make the Little League all-star team. I do acquire a star-shaped scar on my forehead, which I earn by filling a small jam jar with gunpowder I collect by taking a knife and screwdriver to my father’s shotgun ammunition, poking a firecracker fuse through the jam jar’s lid, lighting the fuse, and then standing in a circle with my friends to watch the explosion from 3 metres away. A shard of glass nails me in the forehead hard enough to knock me cold for a few seconds, and my closest friend catches another shard in his leg just below the knee. Two weeks later, he and I will blow up his mother’s concrete washtubs with gunpowder we’ve manufactured from scratch.

In other people’s lives, a second railroad arrives in Prince George; politicians deposit tons of bullshit about all the wealth the railroad will bring when most of what it brought were empty railcars to haul away the trees and hungry people looking for jobs. A P-38 Lightning crashes into the sandbanks across the river at 500 kilometres per hour after buzzing the main street of town at 30 metres; the city’s population doubles, the roads improve and pavement multiplies; my father’s business prospers; and trees, many trees, come down. Life in northern British Columbia, in other words, is normal.