Читать книгу Human Happiness - Brian Fawcett - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe Sociological Script

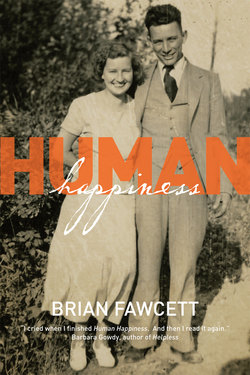

IN 1945, my parents’ marriage, then in its tenth year, was as troubled as it was solid. My father, who’d been forced to quit school in the seventh grade when he left home, had a first-rate brain, courage, and an eye for making money. He’d worked his way from the delivery trucks of a meat-packing company to travelling salesman, and by the end of the war he held the largest territory his company covered, and was looking for other ways to build up enough capital to buy a business of his own. Within the definitions acceptable at the time, he was an excellent provider, and a capable if emotionally limited parent and husband. My mother suffered from mild bouts of depression even though that wasn’t a recognized affliction at the time, socially or clinically, and she harboured profound resentments toward my father. Some were private and specific, some were generic enough that they might have been found in a sociology textbook 25 years later.

Part of the conflict between them was larger than they were. It was the product of the Second World War. Yes, the war lifted North American women’s horizons. But it had made their men heroic, whether they’d been soldiers or not. In 1945, unless you’d spent the war in a jail or under a rock, you were a hero, man or woman. Everyone’s sightlines were elevated. The just and logical gender goals of women like my mother were soon enough cancelled out by the elevated personal outlook—mostly aimed at business goals— of men like my father. This served to turn postwar domestic life, for many married couples, into small, intense contests of will and barely perceptible wars of attrition.

Yet sociology depersonalizes too much. To my mother, her situation didn’t feel like a bloodless element in a statistical formula. Her circumstances were oppressive, and she was distressed by them. By the beginning of the 1940s, she had birthed three children within 18 months of one another, and then she’d had to care for them with little help from my father. She felt abandoned by the man with whom she had chosen to make a life, and she was angry at him— angry enough to have gotten pregnant without his consent, and initially, at least, against his will. She had the right, and she exercised it, but even a fourth child, one she had time to enjoy, hadn’t cooled the anger. It was there, an undertow hidden in the calm currents of their outwardly happy life. Months and sometimes years passed without its poisonous stream reaching the surface. Yet it was there, and it would remain.

Let me try to disentangle this back eddy with a very specific vignette, one without a shred of slapstick in it. My father, in the spring of 1940, returned home late one Friday night after a week of selling on the muddy roads of mid-eastern Alberta. The next morning, he ate a hearty breakfast that my mother made for him, and then took off for the day to play golf with some business friends.

They’d only recently moved to Camrose, then a dusty farming town 80 kilometres southeast of Edmonton. They’d been married in Edmonton in 1936 and both of them had spent most of their adult lives in that city. My mother knew no one in Camrose, and she had, with little domestic help or adult companionship, three children under the age of 2 1/2: my twin sisters, born in April 1938, and my brother, born in October 1939. She wasn’t used to the isolation, and she found herself carrying a domestic load that was heavy and more than a little frightening.

Try to imagine the exchange between the two of them when he returned from the links late that afternoon.

Or rather, don’t, because it will be very unpleasant. It would begin with a young, overtired wife bickering at a young, self-involved husband who doesn’t think domestic duties, even the kind that involve very young offspring he is proud to have fathered, are his responsibility. This is the primary marital tableau of the last 70 years in Western countries, the one that produced feminism, radical feminism, millions of divorces, and uncountable hours of squalor and misery, personal, marital, and civil.

These two were civilized people, so the exchange would not have featured histrionics. No dishes would have been thrown, no one tore out their hair, no doors were slammed. My mother would likely have sulked for several hours, my father might have asked what was wrong, and she might have tried to explain, with some sharpness in her voice, that she was exhausted by the children and anxious about the isolation; not having family close by for company and help, not having close friends for companionship while he was out and about. For god’s sake, Hartley.

My father might have offered a half-hearted apology, swiftly followed by an excuse: he worked hard all week, he needed to unwind, and the Golf Club was a place to meet the local businessmen—for him, actual or potential customers. Privately he would have shrugged it off: women are high-strung, lazy, prone to be controlling—this last item was to become a lifelong theme for him. But also this. Since he knew better, he’d go golfing again next week if the weather was good. Customers to talk with, relaxing to be done. He was in charge, he was a man of his time.

My mother’s case is stronger, but only through twenty-first-century eyes. For their time and locale, neither is decisively wrong or right. Most domestic wars start here, with missed signals, lazy self-regard, and the absence of evil intentions. But the wars start anyway, and before long few combatants can remember what is was that touched off the fighting or what, exactly, they’re fighting for. But the wounds are inflicted, they bleed and fester, and half a century and then some passes in a flash.

My mother was vulnerable and alone, and for her, there was nothing abstract about it. She did not sense any sociological currents moving around her, did not imagine that she was a part of any groundbreaking movement, and she had no revolutionary zeal. There were the long days with only the demanding company of her three toddlers, and the longer nights in the chilly little house in a cold bed. She kept things together: stoked the wood furnace, did the wash on the primitive washboard and tub, and she fed wood and coal into the stove in the kitchen. In the winter she shovelled the snow from the sidewalks, bundled up her babies and took them out into the flat and windy streets, nursed them through the croup and the mumps and whooping cough, always alone. She’d been abandoned, and she experienced the crushing loneliness of this, along with small eddies of fear that it was a loneliness that wasn’t going to be temporary. She stared at the wall, gazed out the kitchen window, didn’t read novels because they made her feel disoriented and separated from her children, the ones she couldn’t bear to be parted from even for a few hours. What could she do about her isolation?

She was resourceful, and not shy. There were other women’s husbands out on the links with hers, weren’t there? Wouldn’t they feel as she did, that things weren’t right? She knocked on her neighbours’ doors, told them who she was, and then cultivated the ones she liked, the ones who shared her situation, building a small community for herself. She joined the local Women’s Institute, found that most were farmers’ wives, more likely to be beaten up for bickering than left alone. On the radio one morning, after the radio soap Laura of Laura Limited (“a woman,” the show’s announcer explained each morning, “who lived by the dictates of her own heart”), she heard about a newfangled women’s organization called Beta Sigma Phi, which had recently formed an inaugural chapter in Edmonton. Several months later she started a chapter of her own in Camrose and when the family moved to Prince George in 1943, she started another. She wasn’t trying to change the world, but she did sweeten her life a little, and it gave a backhanded confirmation of the anger she harboured: women’s lives were hard even though they were safe and secure and the future was bright and about to be filled with washing machines and electric stoves and gas furnaces. But those bleak Monday mornings remained bleak, and the nights remained lonely.

I don’t think my father ever quite understood why his wife was angry or how deep the anger ran. But after five years of intermittent hostility and a move to a town still more isolated than Camrose, he began, slowly, to tune out domestic life and to focus his prodigious energies on the business opportunities that would enable him to make his fortune. He’d be what his wife once told her father she was marrying for: a good provider who promised to have her, one day, riding in a Cadillac.

Be careful what you wish for, I guess.

Neither of these people were dreamers. They didn’t wish they could wear velvet coats and go to the symphony. They were practical people with goals, focused on financial security and social success, not on culture or personal achievements, of which there was little to be had anyway. For them, their children’s education was an obligation, a means to an end, nothing more. I don’t think they imagined any of their children going beyond high school before going into the business world to make fortunes of their own.

After 1945 the years passed, some slowly, some momentous and swift. The ideal children grew, the ideal parents grew older. Quirks grew into fixations and neuroses, and some of their disappointments into grudges and phobias. The sunny future of Hartley Fawcett and Rita Surry turned into a stream of present days and nights that bore no resemblance to a fairy tale. The backlighting was dim and the orchestra didn’t play at all. Everything changed, and nothing did. Dreams submerged beneath the twisting currents of the world, altered and scarred by time, fouled with the debris of daily life. Rough beasts slouched across the landscape, going nowhere. The centre didn’t disintegrate, but it was often hard to locate.

Don’t get me wrong. Most days, they were cheerful and engaged, and focused on their goals. Like the majority of people lucky enough to have lived in North America in the last century, they experienced real-world happiness as a common occurrence. It was as common as oxygen, nearly as invisible, and almost as crucial to survival.

That makes them very different from their ancestors. In the deep past, my parents’ parents and more distant ancestors had spent their lives trying to keep their heads above the murky water, trying to get themselves free of other people’s treadmills, too busy surviving to offer the past a goodbye or the future much more than a shrug toward the horizon as they left to work the fields. My parents could see a brighter future than that, and were wholly focused on getting to it. They didn’t have a sense of either continuity or history because they had broken with the past and with the way people had done things in the past: families that exploited or abused one another, soldiers who had killed one another, bosses who put their boots on your neck and pushed your face in the mud, countries that invaded one another or dropped bombs on peaceful cities. That was over, and they were determined to leave it behind. Yet they didn’t see themselves as exemplary or heroic. They were ordinary people working their way toward a better future. Their world was a bright place, the future brighter still, and they were content to be who they were, and where they lived. But the sun doesn’t shine every day.

In the future they got, many things got better for them. My mother got her appliances, there was less drudgery for her, her children all grew up and married and had children of their own. Some of her wishes were fulfilled, most of my father’s were, but some of the things they wanted proved impossible or empty or preposterous. Gradually, the ideal family of 1945 descended into nuance and an ordinariness that brought pain to both my parents in different ways. The city my father predicted would have a million citizens at the millennium had barely 100,000 at the beginning of the twenty-first century, its forests depleted by logging and self-inflicted ecological catastrophe; its wealth stolen by the corporations or merely squandered; crime was rampant; and the city was losing population daily.

Imagine these two people on a wide river, not as flotsam, yet not as smug boaters on a Sunday lake. They see the river’s restless power clearly, its currents and eddies, and they accept that rapids and whirlpools might lie ahead, even though they have no deep expectations about absolute or final destinations, spiritual or tangible. Imagine them in a small blue boat drifting downstream. They are looking for ways to move their boat here and there, side to side— not to get to the shore but to avoid the hazards of the currents, and to take advantage of them. My mother leans over the water, sculling distractedly. My father sits upright, scanning the river for the means to devise a paddle—or better still, a set of oars so they can ply the currents together. It is April 1945. And, in the blink of an eye, it is December 2000.