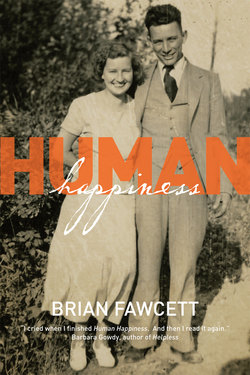

Читать книгу Human Happiness - Brian Fawcett - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHE LAST TIME I TALKED to my mother, she announced that she hated my father. This was a couple of days before the end of November; she was in Penticton, B.C., and I was in Toronto. I’d called her on the telephone to ask about a recipe for Christmas cookies, but that wasn’t really why I called. While I talked to her the week before I’d heard something odd in her voice, and I was checking to see if it had dissipated. It hadn’t.

There’s not a hell of a lot that’s wise or comforting you can say to your mother when she drops a bomb like that. Particularly when she’s 90 years old. You just let her speak her piece, and hope there are no more bombers taxiing down the runway. And of course, hating the man she’d been married to for 64 years wasn’t the only thing she had on her mind. She’d spent the afternoon making the cookies I wanted the recipe for, she’d just packaged up a batch of beef stew into meal-sized portions for the freezer, and was about to start sewing the green net “Nanny Bags” of Christmas treats that had been a favourite of the small kids in the family since I’d been one of them. Did I think the kids still wanted them?

I assured her that they did, although I suspected, in a world filled with more spectacular confections, that they didn’t care one way or another.

“Your father’s supposed to be back from Kamloops any minute,” she said, when I asked about him. That’s when she dropped her bomb. “I can’t say I’ll be glad to see him. I think,” (here was an auspicious pause as she considered what the right words should be) “I’ve finally gotten to the point where I hate him. He’s your father, but I really just hate him. So there.”

The flat finality of it was disturbing, but it didn’t exactly take me by surprise. Things hadn’t been going well between them for a long time, and to tell the truth, the rest of the family wasn’t getting along much better.

We were, at that moment, on the verge of a civil war, with several fronts.

My father had recently delivered his voting shares in the family holding company to my older brother, Ron, and the three of us were snarling back and forth at one another across the new breach it opened. My twin sisters weren’t getting along either, but their squabble, as always, was hard to read. They’re identical twins who live 50 metres apart on Vancouver Island, and to them, everyone is an outsider. When they get going on one another, no one can really understand what it’s about, let alone stop it.

I hadn’t gotten along with my father since before I was a teenager, and my brother had serious issues with my mother, who, in typical fashion, had been arguing my case against my father with Ron about the voting shares, all the while telling me I ought to back off and let my brother take control because, for god’s sake, he’s earned the responsibility. She was trying to get both of us to chill out, but the way she’d been delivering the message was a little too emphatic to soothe either of us. So while it wasn’t quite that the Fawcett family was holding one another at knifepoint, the knives were out, and the last several Family Reunions—annual events at which attendance wasn’t optional—had been very tense.

For as long as anyone could remember, my father and mother had operated a domestic system with sharply demarcated spheres of influence and a strict division of labour. My father kept his fist firmly around the money, and after he retired, he gradually took over all the gardening, which lately involved mowing the grass at high speeds on his sit-down mower, planting exotic roses and spraying them with poisonous chemicals, growing beefsteak tomatoes the same way, and doing a lot of brutal pruning of his and his neighbours trees and shrubs to prevent any obscuring of his view of the Okanagan Valley, which he believed he had a God-given right to view, without obstruction, from his favourite chair in the living room.

My mother kept the house, which she ruled autocratically, most particularly the kitchen, where she was not to be trifled with, even though my sisters and I are equally skilled cooks. She also regulated and sometimes ruled our family life, although she did this with more subtlety and diplomacy than she displayed around the kitchen—or around my father, with whom she’d been engaged in an epic contest of wills since a few years after they were married.

Keeping this family running smoothly wasn’t easy, given its size and the personalities involved. But now the toughest part of her job, since none of us lived close enough for day-to-day contact and mostly showed up at Christmas, Thanksgiving, or the Family Reunions, was my father. At his best, he’d never been easy to get along with, he hadn’t mellowed with age, and in recent years, he was rarely at his best.

He was a man who cheated at cards, practised selective deafness so he wouldn’t have to listen to anything he didn’t want to hear, and regularly pissed off the neighbours by pruning their trees and shrubs without asking. Within the family, he had a long history of offering to lend money and then imposing humiliating conditions after the fact. He had a 35-year record of fomenting Darwinian contests between my brother and I whenever he got the opportunity, and this latest dust-up, was, well, just one of many. He did it, he said, to ensure the growth of his “business empire,” which he’d cheerfully tell anyone, whether they’d asked or not, was the Most Important Thing in Life. I thought he did it to amuse himself, the bastard.

He also made a nuisance of himself at social gatherings by proselytizing right-wing political ideas barely this side of “shoot the poor,” while trying to sell anyone who moved a foul-tasting dietary supplement called Barley Max, which he claimed could solve anyone’s physical ills no matter what they were. When he got going, he’d claim that Barley Max could also cure his client-victims’ spiritual and political shortcomings, which he was fond of pointing out to them in detail as part of the sales pitch.

Given that his eyesight was worse than his hearing and its badness wasn’t at all selective, he was a public menace to everyone and everything whenever he got behind the wheel of his aging Cadillac Fleetwood. He was a still greater menace to the local newspaper’s editor, to whom he wrote long grammar- and spelling-challenged letters about once a week, denouncing the government and whoever and whatever else he thought might be trying to screw with his business empire, or his right to scare the daylights out of unwary pedestrians and other drivers whenever they strayed into the path of his Cadillac.

The family picture wall, which ran 6 or 7 metres along one hallway wall in my parents’ home, was probably the best evidence of the management difficulties my mother faced—and the way she dealt with those difficulties. It had been in flux since the first of my siblings reached puberty, and really, before even that. My father banished his father early in the marriage, and my mother, for different reasons, had banished hers. The wall grew more or less as you’d expect while my siblings and I were growing up: pictures of us in our sports teams and social groups, graduation photos, and so on. These photographs remained constant because they were, each of them, portraits of us the way she liked us best: young and if not exactly innocent, at least unscarred by experience.

When my sisters started bringing home their boyfriends, the wall began to grow. A couple of early boyfriends made it onto the wall, but were replaced by husbands by the time my sisters reached the age of 18. My brother’s wives and then mine started going up a few years later. The grandchildren began to appear, and the wall grew still more.

Getting onto the wall, for outsiders, was easy. Tenure was another matter, as was staying married to any of us. A few legal spouses lasted several years, although one or two lasted only months before they offended my mother and were disappeared. The first ones were all replaced by new spouses or partners soon enough. The live-in boyfriends and girlfriends who replaced them made it onto the wall if my mother happened to like them. New wives and husbands, legal ones, were tolerated even when she didn’t like them— until they in turn were replaced by later models, in which case they disappeared well before the divorce decrees were final. As the grandchildren grew up, they caused a further expansion of the wall, and their first partners were treated with careful democracy when my mother liked them, although a girlfriend of one of my nephews who’d yelled at several of us after we ran her beloved off the go-cart track during the family’s annual takeover of the local facility at the Family Reunion had her picture taken down before the weekend was over. The nephew dropped her soon after.

The picture wall had been moved from house to house by my parents as they got older, and in their last house, a big single-level affair my father insisted would be his last building project, he gave the picture wall its own free-standing wall, a kind of in-family equivalent of the Kremlin’s Hall of Glory. In that last house the wall grew considerably, partly because the family grew in size as great-grandchildren started to appear, but partly because there was space to be filled. It expanded, sure, but it was revised as much as it grew, always by my mother’s increasingly capricious defenestrations. Despite these comings and goings, the wall’s essential fuel remained the 14 divorces racked up by me, my brother, and my sisters.

While my mother and I chatted away that November evening, I thought about how diligently she’d kept the wall current, and I found myself wondering idly if she was now going to remove my father from it while he was still living in the house. But I didn’t mention him again, and it wasn’t very long before the emotional shorthand she and I had developed over the years reimposed the normalities she’d shattered. I copied down the cookie recipe— “Don’t forget the nutmeg”—and I mentioned the idea I’d read somewhere about soaking the Christmas turkey in brine overnight before stuffing it, which she dismissed as silliness. She had her Christmas cards done and ready for mailing, and I told her I had, too, even though I hadn’t started. We talked about some recent minor twinges she’d felt in her head over the last weeks, but said they were nothing. Then we talked about who was going where for Christmas, and then we were up to date. I assured her that everything would be all right, and she agreed that it of course would be, although that same odd note in her voice said otherwise. “I know it’s all a big mess,” she said, and sighed. “But family is important. I don’t want this one to fall apart.”

That was the last thing she said to me, ever. Two nights later, she suffered a major stroke that, among other things, rendered her unable to speak. Twelve days after that, she was dead.