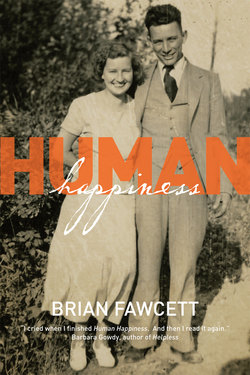

Читать книгу Human Happiness - Brian Fawcett - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеBreast Cancer

IN THE SUMMER of 1960, a few months after my parents returned from three weeks travelling in Europe because my father had won a North American sales prize for selling Pepsi-Cola, my mother found a hard lump in her left breast. Having been warned, even in those distant days, what the lump might be, she booked an appointment with our family doctor, a man named Peter Jaron I remember mainly for having skin rashes on his neck and hands. In a leisurely sort of way, Dr. Jaron arranged for a biopsy, and about a month later called my mother on the phone just as I was arriving home from school. The biopsy, he told her, “was positive.”

“Positive?” I hear her say, with such careful calm that I should have been instantly alert. “What do you mean by positive?”

Peter Jaron’s answer is equally calm. “The growth in your breast is malignant. You have breast cancer. You should come in sometime this week, so we can get the process going.”

“Process?” my mother asks, disturbed by Jaron’s matter-of-fact tone. “What process are we talking about? The process of dying?”

“The treatment process. There’s some urgency about this,” Jaron admits.

“When can I come in?” she says.

There is some fumbling at the other end of the line. “Let me see when I’ve got an open spot.”

My mother slams down the phone, and bursts into tears. I ask her what is wrong. “Nothing,” she says, gathering herself together. “I’ll be fine.”

Satisfied, I wander downstairs to my bedroom, close the door, and begin to work on the 1/25th scale model car I’ve been customizing, a late-model Ford I’ve painstakingly decorated with several coats of maroon candy-apple paint. It looks fine.

But my mother isn’t fine, and over the next several days, she does something about it. She contacts a family friend, Larry Maxwell, a doctor who has recently taken a sabbatical from the local hospital to improve his oncological expertise. He agrees to take her on as a patient, and the worst three years of her life begin.

There are several things about the above tableau you should know. The first is that it is a fabrication drawn from the wispiest shreds of fact and memory. When this reconstruction started, I had just three ciphers to work with, other than the knowledge that my mother contracted breast cancer and underwent a radical mastectomy of her left breast at some point between 1956 and 1966. I had to call my sister Nina to get the dates straight, and we were able to pinpoint 1960 by cross-referencing events in Nina’s life: the breakup of her first marriage, and the subsequent year she and her infant daughter spent living with my parents. It took us a while to sort out the few certainties we could muster between us.

One of the certain ciphers is a memory fragment of mine in which my mother is telling me that I will be going to a new doctor.

“Why is that?” I asked.

She grimaced. “I don’t think,” she said, choosing her words deliberately the way she did when something was difficult, “that Dr. Jaron pays proper attention to his patients.”

The thought of having a new doctor interested me. But maybe it was that I didn’t like Jaron’s skin rashes and the fact that his arms and neck were coated with Band-Aids. Shouldn’t a doctor be able to cure himself of something like that?

“What didn’t he pay attention to?” I said.

She thought about this for a moment. “Well,” she said, “I’ve had a bit of a problem and he didn’t catch it. I don’t want him doing the same thing with you.”

She didn’t mention the word “cancer,” and she didn’t explain what Dr. Jaron had done and not done about her “bit of a problem.” I suspect—now, not then—that he’d been slow to act when she found the lump, and then had been too laconic when the biopsy proved the lump malignant, treating it as if it was her problem and not his. Many years later she told me, out of the blue, that he hadn’t caught it because he didn’t like to touch women’s breasts.

No doubt his casualness after the fact had something to do with covering his ass, as doctors do, then and now, by acting as if everything is routine, what’s the hurry? Yet it might have been more simple. My mother may have decided that Dr. Jaron either lacked sufficient expertise, or interest—who could trust breast examinations to a doctor who didn’t like to touch breasts? So, she took matters into her own hands. When she did that, how could she continue to send her children to him?

Or maybe I just didn’t ask any questions. A new doctor? One without skin rashes? Why not?

The other datum I have is more flimsy still. When she announced that “Larry” Maxwell was her new doctor, she made a point of saying that he was a man that she trusted. I may have thought about asking why—simple curiosity. But more likely, I deduced that she’d gone to Larry Maxwell because he was a family friend with whom she and my father often socialized. I didn’t think to ask why I was now going to a third doctor, which would have forced her to explain what was really going on. When she announced that she was going to Vancouver for a trip, I didn’t ask why, either.

I was, in other words, oblivious to the most catastrophic event in my mother’s entire life while it was happening. My obliviousness didn’t end there, either. I remained woefully ignorant about dates, times, effects of the mastectomy and the several courses of radiation treatments she suffered through over the next several years. Worse, I was utterly without empathy about the pain and suffering she experienced. For instance, I believed that the diagnosis had come in 1958, when I was 14—thus partly excusing my indifference on the grounds of my youth. But it turns out I was 16, and the 3-year crisis from diagnosis through surgery to radiation treatment took me past the age of 18—making me a self-involved near-adult instead of an oblivious adolescent.

I have just three other memories of it to work with, and all three of them are brief and mainly about me.

The first is a vague recollection of my mother coming off the plane from Vancouver with her left arm in a sling. I’d gone out to the small airport in Prince George along with my father and sister Nina—my sister Serena was already married and living in Kamloops, 500 kilometres south, and god only knows where my brother was that day—did my father have him stay behind to deal with some delivery that needed to be made? I remember this event more because of the novelty of going to the airport than any sense of dire occasion. As she descended, very uncertainly, the steel staircase from the plane onto the tarmac, she had, I recall, her light-coloured coat half on, her right arm in the coat sleeve, the left sleeve draped over the sling that immobilized her left arm, obscuring it. I remember being surprised at the sling, and I have to imagine, now, that she was pale. Did she smile when she saw us?

What happened after we picked her up is a total blank. It is blank about the remainder of that day, and blank for months and even years after that. Now that I think of it, I have very few tactile memories of any kind from this period of my life, except for sideswiping a telephone pole with the new-from-the-Europe-trip Volkswagen when my father forced a driving lesson on me as a sixteenth-birthday present.

The driving lesson hadn’t felt like much of a birthday present even before I sideswiped the pole and had to sit through what seemed like the 650th lecture about what a boob I was. I knew my father only wanted me to get my licence so I could drive delivery vans and trucks for him. I had no objection to that, but no burning interest, either. The important thing, in my mind, was that I had no choice. I was correct about not having a choice. Three days later I took my driving test on a 1956 3-ton Chevrolet flat-deck painted Orange Crush colours. The truck, mercifully for me and for the safety of others, had been unloaded for the test. I passed, but I was a lousy driver. I had four small accidents over the next two months before I smartened up and recognized that I had to actually drive the car all the time while I was behind the wheel. In one of the accidents, I drove the Volkswagen through a supermarket window after my foot slipped off the brake pedal and hit the gas as I zipped through the supermarket’s parking lot. Bwam! The others were lapses of attention: I’d decided it was more interesting to do or think about other things. Bwam!

The second memory is wholly fabricated, because I was only told it happened, years later, and it subsequently burned into my brain as an event I’d witnessed. The night before she flew to Vancouver for the mastectomy (Did I go the airport to see her off? Did I try to reassure her before she left?) my father sat her down at the kitchen table and had her sign a dozen blank cheques.

I understood what this was about the instant I was told about it. I was in my twenties at the time, and when I asked, rhetorically, why my father would do such a thing, my mother rolled her eyes and said, “Guess.”

Nah, there was no guessing needed. He’d wanted to be able to clean out her private bank account and the several joint accounts in case . . . Well, I’m sure you get it. It was a horrible thing to do, and it was wholly in character. A sensible woman today would leave a marriage over such a stunt. My mother, a deeply sensible woman, didn’t, and not just, I think, because it was a different era.

The third memory is tactile, and not quite so spare. Several months after she returned home from the operation, she called me into her bedroom.

“It’s time you had a look at this,” she said, her voice matter-of-fact. I was standing just inside the bedroom door as she slipped her nightgown from her left shoulder to expose the vast plate of scar tissue for me to view. I was horrified, by its extent and by the incontrovertible injury of it. Not only was the breast gone, but there was a cavity in her upper chest where the doctors had removed the lymph glands from her left armpit, taking with it elements of her shoulder musculature. The scars were still red and raw-looking, the remaining muscle tissue twisted and cobbled with keloid. (Twenty years later—the next time I had a close look—the scars had changed little.)

“Come here so you can touch it,” she ordered.

I sat on the bed beside her, and I remember caressing her cheek—good for me!—before I ran my hand over the scars. The muscles in my groin contracted as I did, as they do to this day when I recall that moment. Probably, I asked her shyly if it still hurt, and probably, she said “no,” or, “not anymore,” or, “only sometimes.” But maybe I didn’t ask.

What I should have recognized, and didn’t, was how unnecessarily searing an experience it had been for her, both physically and emotionally, and how tough and decisive she’d been through it. My father, never much help when anyone was in physical pain or discomfort, withdrew from her with cruel swiftness the moment he found out about it.

At the end of that conversation with my sister Nina I had to have so I could pinpoint the dates, Nina recalled two extra details. She had a vivid memory of my mother looking frightened as she boarded the plane to Vancouver. The other was much darker. Dr. Jaron, when he got the results of the biopsy, had phoned my father, not my mother. He phoned on Saturday morning, but it was late Sunday afternoon before my father could work up the nerve to reveal what he’d been told. Fifteen minutes later, he left and went down to the plant. He didn’t return home until after ten in the evening. The phone conversation I recorded at the beginning of this took place the next day, and Dr. Jaron had left it to the end of the day to return the call my mother would have made that morning.

My father stayed clear of her for the duration. After the cruelty of the cheques-signings, he delivered her to the plane when she flew to Vancouver for the operation, bringing my sister to the airport to deflect any sharp emotions. He didn’t accompany my mother to Vancouver, excusing himself, no doubt, because his business needed him, and anyway, she’d be in good hands down there, right?

She’d had to arrange her treatment by herself, and now she would see it through on her own: the operation, and then the several further trips south for the radiation treatment that were then customary. I try to imagine what she felt when she arrived at the airport in Vancouver that first time, see her hire a taxi to go to the hotel she’d booked, and I try to imagine what went through her mind as she walked into the hospital with her suitcase, and approached the information desk in the hospital lobby to announce who she was, and what she was there to have done to her.

The follow-up radiation treatments likewise, a process that leaves people poisoned and exhausted for weeks afterward: the same flights on the plane alone, the same terrified entry into the hospital lobby. Each time she must have imagined what should have happened: a car ride across town with her husband holding her hand and her children to care for her while she convalesced.

In the fall of 1962, I took off to Europe with a one-way boat ticket in my pocket and $300 in American Express traveller’s cheques. My urge to get out of town had acted like a giant slingshot, and it sent me 9500 kilometres before I felt the slightest tug in the other direction. I might not have felt any tug at all, but I was in mid-Atlantic when the Cuban Missile Crisis peaked, and it scared the hell out of me. My travelling companions and I spent most of the crisis in the ship’s radio room, watching the captain agonize about whether he ought to turn the ship toward the south Atlantic. I spent several days in that radio room thinking about all the things I was going to miss if the Russians and the Americans blew up the world, and somewhere in the top ten, but not in the top five, was my mother.

When I arrived in London, there was a letter from her worrying that I was okay. I answered the letter, but I wrote just one more letter to her in the next eight months, even though I had to be bailed out of money trouble twice, once by my father and the second time, on the sly, by her. No doubt I missed one of her radiation treatments, and yeah, yeah, kids are always self-centred.

When I returned from Europe, my always-uneasy relationship with my father bloomed into open hostility. Since he’d rescued me when I was in Europe, in his mind that meant that I owed him. He announced that I’d had my fun, and now it was time for me to get serious: come to work for him, get on with my life as a businessman, his assistant CEO, like my older brother.

If I was ever tempted by that, I don’t remember it. But I was tempted by other things—money, cars, the usual things that come with money. When I decided that I needed a car, my mother stepped in.

“No,” she said. “You don’t want a car. If you need one, you can use mine. Owning a car will trap you, and soon you’ll be working for your father, and all those plans you have for your life will go up in smoke. And you don’t have to pay your father back. I will, if it comes to that. You go out and do something with that brain of yours. Be yourself.”

I did exactly what she said, and the battles with my father escalated, occasionally into physical confrontations. As the fights grew more intense, my mother interceded more frequently, and more openly on my side, even when I was just being a jerk. I had no clear idea how I was supposed to “be myself,” but I learned that if I got in my father’s face, I was able to improvise, and the results were dramatic. So when he said yes, I said no. If he said the sky was blue, I countered that it was green, or grey, or black. If I didn’t know who I was, at least I discovered that it was something to not be him, and the more I wasn’t him, the more exhilarating life became.

My mother let me know, never quite directly, that she approved, and I was having too much fun to think about her motives. At one level, I trusted her, so she must have had good reasons. At another, our clandestine alliance served my half-cooked agenda, and I wasn’t so dumb that I didn’t see that it served some needs she had. When she argued with my father, it usually took the heat off me, at least until the next confrontation. Their arguments escalated, as mine did with my father, although theirs never quite got to physical violence. Some of the arguments centred around me, but not all, and maybe not even most. They were at war and I’d chosen my side in it.

There is injury in life, and then there is harm. They’re different, and the distinction is important. The injury my mother suffered from the mastectomy was real and substantial. It was a radical mastectomy, of a kind not much perpetrated anymore, a vicious intrusion into a woman’s body that is both physically traumatic and permanently disfiguring. But it was an injury that successfully healed and because it permitted her to survive another 40 years, she accepted it.

Rita Surry, which is who she had to become in those three years, not the Rita Fawcett she’d grown used to being, or, still more tertiarily, my mother, was a robust woman, and she learned to live with all the physical consequences of what was done to save her life, even finding it a source of entertainment. Reconstructive surgery wasn’t really an option then, and I’m not sure she’d have availed herself of it had it been. Careful as she was about her appearance and grooming, she was not a vain person, and she didn’t for a moment want to accept that she was a victim, or remain one. She showed me the prosthetic breast that provided the appearance of physical symmetry. She referred to it, always with a laugh, as her “fake boob.” For laughs—although not in public—she sometimes would pull it out and throw it at family members. She threw it into my first wife’s lap the first time I brought her home for Christmas, in order, she explained, “to make her feel part of the family.”

But the harm done to her by cancer and its cure was another matter, and I think she sustained more harm than anyone understood, particularly when it came to her relationship with my father. Yes, she survived. So did the marriage, sort of. She survived in no small part because she was as robust emotionally as she was physically, and because in this situation, and through most of her life, she was utterly, coldly competent whenever the shit hit the fan.

“You do what you have to when there’s trouble,” she told me one time when she was in her seventies and I was mired in one of my domestic catastrophes. “You deal with the trouble in front of you, and then you can indulge your feelings. You do it in this order because there are kids depending on you, and because you have to take care of them no matter what you’re feeling. You can deal with your feelings later, when you have time. They’re a luxury, and they don’t help anyone, including you. They’re real enough, but they’re not what moves the mountains.”

She said this without bravado, and over the years I’d seen her practise it often enough that I accepted it—and more important— tried to do the same thing myself, sometimes successfully. My father, for all his ambition and foresight, offered nothing I wanted to emulate. He might have been tough on the street or at his business desk, but he was a man who vanished whenever domestic life got rough. If he responded, it was usually to lose his temper, and when that happened, it was time to get under the nearest table. He was always ready to talk at us, but he wasn’t comfortable with the give-and-take of conversation, not with anyone. If it wasn’t about him or his ideas or his products, he just wasn’t very interested. If it was about you, well, he could offer himself as a model, or give advice or lend you money, generally with so many strings attached to it that it didn’t feel like generosity or help. Then he’d order you to do things his way if you didn’t want him thinking you were an idiot. He couldn’t collaborate with anyone unless there was advantage to him, and even then, it had to be him in control, front and centre.

These are, I now realize, fairly exact enumerations of my mother’s chronic complaints about him, and the primary source of the loneliness that troubled her. The loneliness made her miserable, but she wasn’t destroyed by it. Misery and happiness can and do coexist, and for the years of that crisis, she had a lot to live for: four children, three young grandchildren, a community of people she liked, and a landscape she loved. And so the misery and pain inflicted on her coexisted with the small, intense moments of happiness you could always read in her as near-equal tributaries of her life, like the Nechako and Fraser rivers that met at Prince George. The Nechako in those days was blue and sparkling, the Fraser muddy and fouled with upstream debris from the wild MacGregor River basin, the distant Rockies, and too much careless logging.

I suppose most people’s lives are like those conjoining rivers— a composite of sweet and nasty, experience and aspiration, currents that nurture; shoals and back eddies that diminish and corrode. Or they would be, if human life was something that could be accurately judged in the abstract: overflown in plan view, say, or rendered coherent by the exquisition of physical details and symbolic dialogue, the way flowery novelists do it. Those gods we invent to explain life’s arbitrariness and misery likewise tempt me here, because the hand of God can excuse any transgression.

But this is a real life, lived by a real river, and this is a real woman in real pain. These are components of human happiness, such as it is.