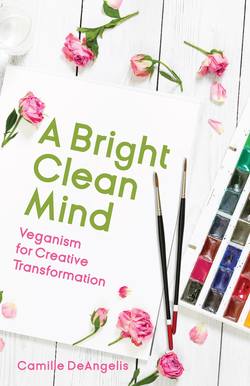

Читать книгу A Bright Clean Mind - Camille DeAngelis - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThis Life of Verve & Loathing

Sticking point #2: “Sometimes I feel totally self-assured, and other times I dislike myself so intensely that I can’t lift a finger to make anything.”

When I was a child, I loved nothing better than to draw. You could give me a small stack of typing paper and a boxful of markers, and I’d be content for hours. My parents sent me to drawing and pottery classes at the local arts center, and my teachers were very encouraging. I had ability, and I took pride in that—maybe a little too much. Our elementary school art teacher used to hang our work in the hallway outside the cafeteria, and I remember waiting in the lunch line, looking up at a row of still lifes—apples, done in pastel—and playing a game of “which drawing is the best?” I’d choose one, and when I got close enough to see the signature, I’d remember with such pleasure that it was mine.

I played this game most lunchtimes until our teacher took down the apples.

I have another clear memory of the South Valley cafeteria. Picture me: seven years old, all knees and elbows, with awkwardly cropped hair thanks to a classroom lice epidemic. I am sitting in front of a Styrofoam tray with a cheesesteak ready to be washed down with a little carton of 2 percent milk. Only this isn’t a proper Philly cheesesteak with shredded beef, onions, and peppers topped with melted American or provolone. This thing is a rectangular slab of reconstituted meat with a blister of lard studding the gray-brown surface. This is by far the most disgusting thing that has ever been presented to me as “food.” I don’t want to eat it, but I do—and then I feel disgusted with myself.

There are specific reasons why we remember what we do out of all the ever-vaster catalog of life experiences, even if these reasons never consciously occur to us. I believe that in these grade-school memories two irreconcilable attitudes about myself are encoded: the self-assurance I would need to pursue a career in the arts and the self-loathing that arises out of a sense of helplessness. Now and then I had my petty rebellions, but for the most part, I was a polite and obedient child; it wouldn’t occur to me for many more years that I could choose not to eat that cheesesteak.

Over time this bifurcated sense of myself became more pronounced. I was assigned to “gifted” classes, and I always scored in the 99th percentile on standardized tests. Yet I was defective. My parents’ acrimonious divorce and ongoing custody battles were a consequence of my inadequacy. My physical imperfections horrified me: mysterious knobs of flesh on my skull, the gap between my two front teeth, the dark leg hair that began to grow before I hit puberty. Physical symptoms led my parents to bring me to the doctor—stomach trouble, an ache in my lower back, shooting pains in my feet—and no doubt the doctor wrote them off as psychosomatic. I went to a series of therapists. I lay awake reading Nancy Drew mysteries well past midnight, the anxiety mounting that I might fall asleep during school the next day, which, of course, pushed sleep off even later.

I started high school, and the symptoms got weirder. The skin on my arms peeled off in swathes, and my fingernails fell out one by one. But I reacted to these developments with curiosity. I was molting, and I took that as a good thing, because by this point I’d become obsessed with the idea of metamorphosis. I watched the 1994 adaptation of Little Women over and over to hear Winona Ryder say of Jo’s writing practice, “I gave myself up to it, longing for transformation.” And I remember sitting in my mother’s car in the library parking lot, feeling her dismay as she noticed the title of the book in my lap: Seven Days to a Brand-New You.

“What’s wrong with you the way you are?”

“It’s fiction,” I huffed—as if I hadn’t wished it weren’t.

I was also fascinated with Sylvia Plath, as sensitive, self-absorbed white girls tend to be. For a senior year English project, I drew a sarcophagus lid with a female effigy in a blue-striped nemes headcloth inspired by “Last Words (Crossing the Water).” Phrases from various poems curved along a chest plate and covered the background: “Morals launder and present themselves,” “Blameless as daylight,” and “I shall hardly know myself,” a reference to the poet’s shining newborn self after death. In Sylvia Plath: Poetry and Existence, David Holbrook writes, “The psychotic delusion is that what is necessary is the destruction of an old self, and the rebirth of a new. In truth she won’t be there to know herself.” As I read this analysis, I wished someone could have coined “mansplaining” a few decades sooner. Oh well, I guess that makes me cuckoo too!

I grew out of that preoccupation with the morbid poets—though I never stopped identifying with them—and, by the end of my twenties, I’d summoned enough “necessary arrogance” (as the psychologist Eric Maisel calls it) to succeed at putting out my first two novels with a Big Five publisher. In the spring of 2010, I was granted a residency at Yaddo, the artists’ retreat where Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes stayed in the fall of 1959, and every day I climbed the winding stairs at West House to the same sunlit study where Plath worked at rounding out her first collection, The Colossus and Other Poems. Some evenings my new friends and I would curl up with a cocktail on the yellow velvet sofa in the drawing room and laugh to one another, “Oh yes, they definitely did the business on this very spot.”

My time at Yaddo was exactly one year before my “vegan conversion” at Sadhana Forest, and in my journal, I mention eggs for breakfast and the Yaddo chef’s infamous chocolate mayonnaise cake. These entries are also tinged with a cheerful sort of insecurity: I think it’s a good thing to surround yourself, on occasion, with people who make you feel slightly obtuse. I told myself the writing was going well, but it wasn’t really. Maybe I’d hoped my invitation to such a hallowed literary institution would change me somehow, give me the validation I needed to silence that desperate voice inside me chirping, “Let me show you how interesting I am!”

But I also recounted conversations in which I articulated (perhaps for the first time) the conviction that artistic development is linked to spiritual growth. Plath knew it too. During her time at Yaddo, she wrote, “[G]et rid of the accusing, never-satisfied gods who surround me like a crown of thorns. Forget myself, myself. Become a vehicle of the world, a tongue, a voice. Abandon my ego.” I wish I could ask her what she meant by becoming a “vehicle of the world”—practically speaking—and I wish I could tell her how I’ve chosen to interpret those words. In letters to friends and family, Plath expressed unease at the pleasure her new husband took in fishing and hunting. One night Hughes took her out tracking in Yorkshire and shot a doe and her fawn, and though Sylvia had been cooking for him daily in his mother’s kitchen, she wasn’t willing to make a stew out of such beautiful, gentle creatures.

© Nava Atlas, The Narcissist’s Library, detail, 2017.

When I went vegan, I finally found the transformation I’d been yearning for since childhood, the natural result of a momentous shift in perspective: for what is my anxiety compared to the seventy billion land animals facing the dis-assembly line each year or the thousands of workers (many of whom are undocumented) who suffer serious injuries and appallingly low wages in order for our meat, dairy, and produce to reach the grocery store? This is not to invalidate what I or Sylvia Plath or anyone else with “first-world problems” have felt, but to suggest we turn our explorations outward and ask what logical steps we can take to alleviate the suffering of others.

I’ve come to believe that an obsession with metamorphosis indicates an impatience, an unwillingness to “do the work” on oneself—to focus on making one kinder, braver choice at a time until you evolve into the person you want to be. There can be no surefire fixes for self-loathing—particularly where mental illness is involved—but ethical veganism may very well provide a philosophical framework that prevents your emotional pain from eclipsing the world around you.

Better Self-Esteem through Emotional Hygiene

My friend Dixie once advised me to “be my own mama,” which is an effective method for managing lingering feelings of self-loathing. The concept is simple: treat yourself as you would a small child in your care. Systematize your self-soothing practice into two types of actions: daily maintenance and strategies for “emergency” situations (e.g., a negative thought spiral). For me, simple maintenance includes making the bed, writing in my journal, going to yoga class, meditating for at least five minutes, and lighting a candle or incense to set a calm and cozy mood in the evenings. (A hand, foot, or face massage would be ideal, too, though truth be told, I almost never do it.) At the top of my emergency list is “headstand for at least ten to fifteen breaths,” which is the only thing guaranteed to turn my mood around. (I would put my head on the floor of a filthy bathroom stall if I really needed to.) The idea here is to be more deliberate about caring for the softest parts of ourselves, so that we in turn can recognize the softest parts of others.