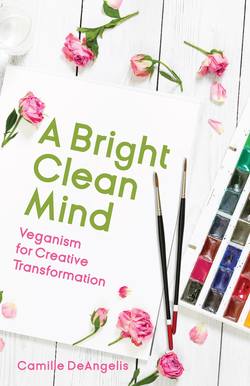

Читать книгу A Bright Clean Mind - Camille DeAngelis - Страница 21

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеLighting the Lamps in the Mind and Heart

Sticking point #4: “I hyper-caffeinate to fend off chronic lethargy. Even when there’s time to create, I don’t always feel mentally or emotionally up to it.”

Google “creativity” and “diet” and you’ll find a series of articles promising optimal brain performance if you eat from their recommended list of “superfoods.” All kinds of berries. Nuts and seeds. Whole grains like oats, quinoa, barley, and amaranth. Avocados. “Sulforaphane for the brain,” as raw-food coach Karen Ranzi says: cruciferous greens like broccoli, kale, brussels sprouts, and spinach. Cauliflower and broccoli sprouts are especially rich in this cognition-boosting (and cancer-fighting) phytochemical.

The only animal foods nutritionists ever seem to recommend for brain health are eggs and salmon (or cold-water fish in general). When I was a kid, my father often quoted a doctor on the radio who asserted that eggs are “nature’s perfect food,” but clinical researcher and professor of medicine Dr. Neal Barnard has since dubbed them “the incredibly inedible egg,” noting that one egg has as much cholesterol as a Big Mac. Eggs make the list only because they’re high in choline, a vitamin essential for brain and liver health, but you can get adequate doses of choline from collards, broccoli, cauliflower, brussels sprouts, asparagus, tofu, quinoa, and other plant sources instead.

As for salmon, the fish flesh you purchase at the supermarket most likely comes from intensive-confinement farming operations in which the poor creatures are forced to swim in their own feces. The types of omega-3s for which fish consumption is touted—DHA and EPA—actually come from the algae the fishes eat, and the human body converts a certain amount of ALA to DHA and EPA. So even if we’re not sure we’re getting all the omega-3 fatty acids we need from ALA-rich walnuts, flax, leafy greens, and other land sources, we can use algae supplements for DHA and EPA instead of fish oil, which tends to go rancid (and may be tainted with mercury).

Scientists have found that a traditional Mediterranean diet—high in vegetables, fruit, beans, and nuts—may lower your risk of Alzheimer’s and cognitive decline in general. “When researchers tried to tease out the protective components, fish consumption showed no benefit, neither did moderate alcohol consumption,” writes Dr. Michael Greger, a medical doctor who specializes in clinical nutrition. “The two critical pieces appeared to be vegetable consumption, and the ratio between unsaturated fats and saturated fats, essentially plant fats to animal fats.” Greger recommends a vegan diet in bestselling books like How Not to Die.V

When you live by the standard Western diet—with super-high cholesterol and saturated fat from red meat, poultry, eggs, and dairy—all that gunk has to go somewhere, so over time it turns into plugs in your arteries and plaque in your brain. The effect is the same even if you consume these foods in moderation. So, if you want to keep coming up with brilliant ideas well into your golden years, quitting animal products is the best decision you can make. Mind you, I am not a nutritionist, but I have been vegan for seven years now and my thinking has never been clearer.

Kerry Lemon, a very talented and prolific illustrator from the UK, reports the same since going vegan four years ago, and she also experienced a more consistent energy level. “I no longer have the three o’clock slump, and heavy feeling after meals,” she wrote me. “I used to have to plan creative activities for the mornings when I was at my best but am now able to work creatively at any time.” Artist and vegan lifestyle coach Vicki Brett-Gach concurs: “I have more creative energy (and feel it more consistently) than I had before I was vegan…now, I practically bounce out of bed in the morning and cannot wait to dive into my creative work. And I long for it like I never had before on the days when my schedule doesn’t permit [it].”

Physiological recalibrations occur whenever you make a long-term change in your diet, but when you go vegan, the cognitive shift is even more remarkable. “Not only did I lose weight, I also noticed better mental clarity,” Adama Maweja writes in her essay “The Fulfillment of the Movement.” “My mind opened up. It was as if I’d been in a dark room or tunnel, when suddenly a bright and brilliant light was turned on. I went to class, paid attention, and understood things at another level. I no longer had to labor over my books as before. I began to ask questions and make points that could not be countered. I could hear what wasn’t being said and could read between the lines.”

My experience was much like Maweja’s, especially the light I saw above my head during that pivotal conversation with my friend Jamey; though in my case, it felt more like Dorothy stepping out of her black-and-white farmhouse into a world of technicolor. I felt like I’d been given a neurological upgrade: a brand-new mind, bright and clean. Ideas, good ideas, came rushing forth as they never had before—a leveling-up of what midcentury psychologist and creativity expert J.P. Guilford called the “fluency factor”: “the person who is capable of producing a large number of ideas per unit of time, other things being equal, has a greater chance of having significant ideas.” Guilford also wrote that a creative act requires a change in thought or behavior and that creativity flourishes through mental flexibility, or a willingness to consider new ideas. In researching this book, I’ve shaken my head time and again at the wisdom we’re encouraged to apply to every aspect of human life except the torture and consumption of animals.

But the clarity I experienced was primarily psychological. I began to notice all the myriad little lies we tell ourselves and each other. I only eat animals that lived good lives. May all beings everywhere be happy and free, except those destined for my dinner. My diet is healthy because I want to believe it’s healthy. Feedback loops and confirmation bias became too obvious to ignore, like a spaceship landing in a public park in broad daylight. Over the past seven years, I’ve channeled these new insights into my writing, and while one could argue that my recent work is more fully realized simply because I am older and therefore more practiced, there is no other explanation for this sustained level of productivity when I once languished in those year-long troughs.

Put another way, the quality and quantity of my output increased with the quality of my input. When poet and musician Saul Williams taught a class at Stanford called “The Muse, Musings, & Music,” he stipulated that each student had to go vegetarian for the semester in order to pass. Some were furious—they’d registered for the class expecting a famous slam poet to read their poems and pile on the praise. What the hell was this BS? Williams told the complainers,

Oh, you want me to monitor your creative output? Why would I want to dig through your shit if you’re not paying attention to what’s creating your shit? Why should I monitor what comes out of you if you’re not monitoring what goes into you? You think there’s no connection? What you read is your diet. What you watch is your diet. Channels? Dumb shit? That’s your diet. What you listen to is your diet. What you talk about, what you allow to be talked about in circles around you? That’s your diet. That’s what you’re ingesting…So you’re digesting all this shit and trying to come up with something original? You’re not surrounded by originality. How do you expect it to come out of you?

I suppose someone who cares too much for propriety might be put off by the scatological nature of this argument, but Williams is spot on, in art and in general: owning our waste means taking responsibility for what we’ve chosen to put in our mouths (or let into our consciousness) to begin with. The old notion of passively waiting for the Muse to bless your efforts is now a matter of readying oneself by eating and otherwise living well.

In a piece called “Unleashing Creativity” in Scientific American, Ulrich Kraft offers “Steps to a Creative Mind-Set,” chief among them being “Intellectual courage. Strive to think outside accepted principles and habitual perspectives such as ‘We’ve always done it that way.’” But I’m not too confident Kraft would apply his “intellectual courage” to the contents of his refrigerator. He continues: “To a degree, the brain is a creature of habit; using well-established neural pathways is more economical than elaborating new or unusual ones. Additionally, failure to train creative faculties allows those neural connections to wither. Over time it becomes harder for us to overcome thought barriers.” When people ask about my lifestyle and I reply with standard vegan logic, it’s exceedingly rare that someone will respond to any of my points with “intellectual courage.” More often than not, they ignore much of what I’ve said and walk away from the interaction thinking, “Camille loves animals. Isn’t that nice.” Those neural barriers are too reinforced.

On the other hand, we can use neural grooves to establish positive new eating habits. As vegan dietician Matt Ruscigno says, “It is really easy to stay in a rut and very difficult to get out of a rut. We forget that it takes time, and that it’s hard in the beginning… For those of us [vegans] who say it’s easy, it’s because we’ve developed new ruts.” The one true challenge is in resolving to forge that new neural pathway to start with; we just have to persevere to the point where a new habit feels as natural and comfortable as a longstanding one.

We hear doctors’ standard advice for slowing cognitive decline all the time: make a practice of doing things differently. Even good habits like cardiovascular exercise and oral hygiene should be practiced in new ways (like brushing your teeth in tree pose, for instance). Be deliberate about creating new neural pathways, they tell us—that’s how we stay sharp. What we don’t hear so often, though, is that changing your diet is the fastest, easiest way to a clear and fertile mind. It is a logical, specific change you can implement immediately.

Improving Your Input

Commit to a simple positive dietary change for at least one week: fresh juice or a smoothie in the morning (see page 195 for a list of my favorite combinations), a big salad rich in plant protein for lunch, or fresh fruit instead of cookies or ice cream (if you like to work at night). Each day make a note of what you ate or drank and how you feel, both physically and about how your work went that day (being as specific as you can in your observations). If you didn’t notice an appreciable difference, switch things up the following day: try a green smoothie instead of peanut-butter-and-banana, for example, or a three-bean salad with a tangy dressing instead of the vegan Caesar. Keep experimenting until you’ve found the foods that fuel you best.

Herbs and Spices to Light You Up

You probably already know that ginseng and gingko biloba are known to promote cognitive health, but the next time you’re at your local health food shop, look for gotu kola, which is scientifically proven to oxygenate the brain and activate neural pathways. Adriana Ayales, owner of the Anima Mundi Apothecary in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, suggests shaking a daily “herbal cocktail” with raw coconut water, 1 teaspoon gotu kola extract, and ½ teaspoon flax or borage seed oil (for omega-3s). You can also drink gotu kola as a tea by decocting in simmering water for fifteen to twenty minutes.

In a New York Times interview, Serbian artist Ana Kras shares her recipe for a morning chai latte she says boosts her immune system and brings mental clarity. Along with organic masala chai spice, ground vanilla powder, and homemade cashew cream, Kras recommends using Ayurvedic herbs like ashwagandha (dubbed the “Indian ginseng”), which several studies indicate may relieve stress and anxiety, and mucuna pruriens, a legume with anti-depressant effects; and powdered fungi like reishi and cordyceps. Kras, who is vegan, savors a cup of this “potion” along with toast and fig jam each morning before she gets to work. You’ll spend a good bit of money at the health food store, she says, but the powders last a long time, and the mental boost is totally worth it.

Nothing gets me feeling full, cozy, and ready to write like a nice hearty vegetable curry with tofu or chickpeas, and it turns out that turmeric—“king of the spices” and an essential ingredient in curry powder—may fight brain plaque and keep nerve cells active as we age. Along with cumin and coriander (which also go into curry powder), turmeric boosts digestion. Adding freshly ground black pepper maximizes your turmeric absorption, and you can also juice fresh turmeric root for a “golden milkshake” or latte. Studies indicate sage and lemon balm can also stave off cognitive decline, so use these herbs in your cooking (or drink in tea form). Ginger, juiced or added to a curry or stir-fry, is another effective digestive aid; after all, the smoother things are moving down there, the more energy and attention you have for your work!

Whatever you’re eating, make sure your meals are as colorful as possible—that’s how you know your food is rich in phytochemicals, which are powerful antioxidants. In general, as vegan “artivist” Sara Sechi puts it, “A positive and colorful diet makes a positive and energetic individual.”

© Nicola McLean, 100% MY Wool, acrylic, 2019.

Rendezvous with Fate

Sticking point #5: “I feel like I’m riding in the passenger seat of my own career (and life).”

Several years back I made a friend—a fellow writer, enormously talented—who quite enjoys her bacon and sausage, and over dinner one night, we got to talking about disease and genetics. “I already know how I’m going to go,” she announced. (She was still in her twenties at the time.) “My family has a history of heart disease.”

“People say that, but it’s not your family medical history. It’s the fact that you’re all eating the same food,” I argued. “You won’t die of heart disease if you stop eating meat and dairy.”

I’ll never forget the look she gave me: the wide puppy-dog eyes, hands palm up, an exaggerated shrug. It was a gesture of utter helplessness. No, really, it’s out of my control. Then she calmly took another bite of her shepherd’s pie.

And I swallowed my frustration. My friend is every bit as intelligent as I am. I could have offered her plenty of scientific research to support my claim, had she asked for it: depending on which source you consult, only 5 to 10 percent of all cancers are genetic, and even if you do have a genetic predisposition for cardiovascular illness, physicians like Dean Ornish and Neal Barnard have proven that eliminating animal protein will flip the figurative switch, even in cases where the disease has begun to manifest. Plant foods contain no cholesterol and tend to be low in fat. It doesn’t matter if what you’re eating is “lean,” or “white meat,” or “grass-fed free-range organic”—all animal protein promotes these diseases.

Why wouldn’t my friend listen to reason?

Because as Jessa Crispin points out in Why I Am Not a Feminist, it’s “[e]asier to think we are rendered absolutely powerless than to think we choose powerlessness because it is more convenient.” For many people, cutting out what have been comfort foods from childhood is too grave an inconvenience to contemplate. As my teacher Victoria Moran writes in The Good Karma Diet, “If you have the necessary information and you’re still saying, ‘I could never give up…,’ listen to yourself. You’re affirming weakness. There you are, created, the Bible says, in the image and likeness of God, and you’re brought to your knees by a scoop of French vanilla.” The celebrated South African novelist J.M. Coetzee elaborates on this ubiquitous phenomenon of psychological enfeeblement in the foreword to Jonathan Balcombe’s Second Nature:

Ordinary people do not need to have something proved to them scientifically before they will believe it. They believe it because their parents believed it, or because it is accepted as so in the circles in which they move, or because figures of authority say it is so. Mostly, however, people believe what they want to believe, what it suits them to believe. Thus: fish feel no pain.

This voluntary disempowerment happens to a certain extent in our creative endeavors too. It’s so easy to fixate on factors beyond our control—who is inclined to recognize and promote our work, how much compensation we’re receiving compared to other artists—and in doing so, we fail to recognize the power we do have. If somebody whines because their novel or screenplay hasn’t sold or if they plummet into existential crisis because nobody is buying their art, we tell them to pick themselves up and get back to it. We don’t feel sympathetic toward those who don’t do the work they need to do in order to succeed. Why do we expect people to take responsibility for their decisions in every aspect of life except their personal health?

Of all our cultural taboos, this I see as the most tragic. A heavy meat eater has a heart attack or is diagnosed with cancer, and we are expected to react with complete sympathy, as if the disease chose them at random. The patient’s diet is “the elephant in the room,” even as an orderly arrives with a lunch tray brimming with highly processed, chemical-laden animal products—right down to the cherry Jell-O jiggling in the little plastic cup.

Truth is—unless the options available to you are the result of systemic racismVI—your diet can never be a “personal choice,” because what you choose to eat affects both the animals who die to become your dinner and every human in your life who will bear the burden of caring for you when you get sick. Blaming bad genes while continuing to eat food that research has proven time and again to be detrimental to our health would, in a saner world, be one definition of insanity. It makes me wish people would just come out and say “You know what? I love steak and hamburgers so much that I really don’t care if I end up on an operating table twenty years from now.” That, at least, would be honest.

And yes, there will always be anecdotes of spry centenarians who indulge in bacon and cigars on a daily basis, but as vegan dietitian Marty Davey quips, “Everybody has an Uncle Fred—the rest of us follow biochemistry.” It’s not intelligent strategy to live as if you’re destined to be one of the outliers.

This isn’t a hypothetical, either. A colleague I met at a literary festival over a decade ago, a bestselling thriller writer, recently posted on Facebook that he is facing open-heart surgery. Needless to say, he is scared out of his mind, and hundreds of friends left comments with heartfelt wishes for his swift recovery. I wanted to be one of those friends. But if I were to message him and say, “Hey, once you get through this, look into switching to a plant-based diet, okay?”, my concern might read too much like sanctimony. I can only hope this friend discovers the medical research on his own.

Kerry Lemon went vegan to help heal an illness, and looking back on that difficult period, she says, “I now feel oddly grateful that I became unwell and was forced to live a more ethical life.” So, you, the artist, have a critical decision to make—a choice you still make by changing nothing. You can take the risk of, twenty or thirty or forty years from now, logging weeks in a hospital bed awaiting triple-bypass surgery, enduring the indignities of Jell-O for lunch and your bottom hanging out of a skimpy blue hospital gown.

Or you could do what you need to do to ensure that at seventy, eighty, and ninety years of age, you’ll be at your desk or easel or microphone where you belong.

Better Choices = Better Health = Better Art

Stepping into your creative destiny requires accepting responsibility for your actions (and inactions). Open your notebook and spend some time considering how you might be giving your power away.

Part two: are you able to see your creative practice in a more holistic manner—to recognize that sound physical health results in greater productivity and artistic satisfaction?

If you don’t feel ready to eschew all animal products just yet, make a note of everything you eat for the next three days, including portion estimates. Then visit the USDA National Nutrient Database (https://ndb.nal.usda.gov) and make a note of the saturated fat and cholesterol content of each item. Tally it up. You may be shocked at what you find, especially if you like to think of yourself as a relatively healthy eater. Once you’ve switched to a vegan or mostly-vegan diet, you can use this site to tally up the protein content of everything you eat—and as long as you’re eating balanced and colorful meals, that number will be a pleasant surprise.

V Incidentally, America’s most famous pediatrician, Dr. Benjamin Spock, recommended a plant-based diet for children in his seventh and final edition of Dr. Spock’s Baby and Child Care, published in 1998 (two months after Spock passed away at nearly ninety-five). Spock himself had begun eating vegan in 1991 after a series of illnesses, and in those last seven years he enjoyed a fifty-pound weight loss and increased mobility.

VI It isn’t a simple matter of “personal choice” even when fresh produce is available, as Starr Carrington writes in “Food Justice and Race in the US,”. “Before imposing shame upon the consumer, one needs to truly analyze the difference between accessibility and affordability.” (187) Check out Madrabbits.org for solid advice on eating well in a “food swamp” and/or on a fixed income.