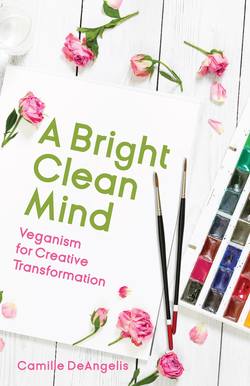

Читать книгу A Bright Clean Mind - Camille DeAngelis - Страница 25

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеWallpaper Girl

Sticking point #8: “This market is so saturated that it’s more important than ever for me to position myself to STAND OUT.”

In early 2015, I met a friend of a friend with a presence that was warm and familiar, and when I found out what he does for a living, I felt a cosmic tap on the shoulder: you need to work with him. Tim is more than a coach or a therapist; his approach is a combination of talk therapy, life coaching, and energy healing, which sounds like baloney until you experience it for yourself. I wanted to tell more meaningful stories, to write books that would truly help and inspire people (in addition to entertaining them), and I wanted to feel that I deserve to make an adequate living from my writing.

In our epic monthly sessions, we worked on all that and more, and I felt more clear-headed and empowered than ever. But when Tim would say things like “I see you becoming a voice for the women’s movement,” a small but undeniable part of me wanted to shrivel up and hide under the futon, so we had to examine that too. Tim occasionally hosts personal-growth workshops at his home—a cozy nineteenth-century farmhouse north of Boston—and during the one I attended, we paired up and sat facing one another making steady eye contact, taking turns “witnessing” and “being witnessed.” When it was my turn to be witnessed, I gave in to the urge to take off my glasses so that my partner’s face was fuzzy. This way I wouldn’t have to look at her looking at me. “This is stupid,” I whined to myself. “What the hell is the point of this?”

Alfredo Meschi, Project X. Photo by Sara Morena Zanella.

@alfredomeschix

By the end of the exercise, I was longing to remove myself from the room. I said “excuse me,” as if I were only going to the toilet, and instead I hurried down the long corridor to Tim’s dining room and ducked under his massive antique table, where I cried as quietly as possible. In my world, it doesn’t qualify as a revelation unless accompanied by copious amounts of tears and snot.

A little while later, Tim—that blessed man!—came into the dining room and sat down on the carpet beside me. “I thought it was odd that you seemed so resistant to that exercise,” he said gently. “Well, now we know you’re afraid to be seen.”

Even if you’re not a visual artist, I bet you have recurring images in your head just like I do—pictures I may someday get around to drawing or painting if I don’t outgrow them first. The most resonant of these is from my teenhood, a self-portrait in which my skin matches the pattern of the intricate William Morris paper on the wall behind me. A paradox still asking to be painted in oils.

It defies logic, I know. I wanted so badly for my novels to be “taken seriously,” yet I felt nervous and embarrassed whenever I received a glowing review or an invitation to appear at a bookstore or festival. I’d like to have a larger following on social media so that more people have the chance to read my helpful books—this one and Life Without Envy—but the prospect of having to manage the inevitable snark and trolling, perhaps multiple times a day, totally turns my stomach. I want to “stand out,” but it’s more important never to feel exposed or unsafe—or at least this has been my subconscious reasoning. When writer and cultural critic Jill Louise Busby posted a video in which she says, “We are obsessed with comfort and security, and that is not revolutionary,” I felt a sharp tingle of recognition.

There are several reasons why I haven’t been comfortable making myself “too visible,” too many to delve into here. The point is that we can’t fulfill all the good we’re capable of if we’re too afraid of being insulted or laughed at or willfully misunderstood. It’s one thing to “play small” to avoid making your partner, parents, or friends feel insecure (to the point of resentment, perhaps) that you’ve become more successful than they are; it’s an understandable impulse though it serves no one. But when you can’t find it in you to clear your throat and say what needs to be said, to stand up for those who aren’t able to stand up for themselves, you fall into line with all that is conveniently unjust in this society. Same goes if you are seeking recognition in order to feel wanted and adored—if your art ultimately benefits no one but yourself.

When we feel the drive to announce ourselves, to take up space and snatch a few precious seconds of attention for our work, it is a useful exercise in ego management to consider the forced invisibility of others. Hip-Hop Is Green founder Keith Tucker introduced me to the concept of symbolic annihilation, developed by George Gerbner in 1976 to describe how members of underprivileged groups are underrepresented and misrepresented in the media—if they’re represented at all—using stereotypes and denying individual identities in order to maintain our current system of social inequality. In 1978 sociologist Gaye Tuchman expanded on the concept, writing that symbolic annihilation manifests in three ways: by omission, trivialization, and condemnation. “That’s why you don’t see me on TV,” Tucker says. “You don’t see [hip-hop artist] KRS-One’s music playing anywhere. You don’t see other artists who are talking about meaningful things…it’s been omitted.”

But Tucker would agree that no one is less seen than animals in factory farms; as the adage (usually attributed to Paul McCartney) goes, if slaughterhouses had glass walls, most people would choose vegetarianism. When you look down at your breakfast plate, you don’t see the filthy crowded cages in the eggs or the dis-assembly line in the bacon. In your cheese or yogurt or veal, you don’t see the calf torn from his mother’s side, crying out for her milk and her warmth and comfort. It is a bizarre thing that an artist like me should want so ardently to be seen and appreciated while supporting these invisible cruelties.

Some artists look for ways to draw attention to themselves for the animals’ benefit. PETA’s been doing this for years with commercials featuring celebrities like Mya, Mayim Bialik, RZA, and Pamela Anderson, and these ads have been much more effective than their ill-conceived (and indeed racist) campaigns comparing factory farming to human slavery and genocide. You watch a talented singer like Mya twirling in a dress stitched entirely out of vegetable fronds, and when she tells the camera, “I no longer see product—I see process,” you feel inclined to consider her point. Another PETA activist, vegan chef Nikki Ford, uses her body to protest the use and abuse of circus animals. “She was a traffic stopper, for sure,” wrote one journalist in Greensboro, North Carolina. “Nearly naked with her body painted like a zebra, Nikki Ford had men craning their necks for a look as she stood at the intersection of South Elm Street and East Friendly Avenue early Tuesday afternoon. But it wasn’t her body that Ford or the two women with her wanted passersby to notice. It was the sign she held that read: ‘Get Animals Out of UniverSoul Circus.’ ” One might argue Ford is objectifying herself, but her message is far more memorable than if she were carrying it on a sign. Same goes for ANIIML, a musician, performance artist, and animal-rights activist who says, “I see the body as the most beautiful, most controversial, and yet most basic piece of art we are given to create with and from.” In her headshot, her left eye has been Photoshopped to look like a cat’s.

Even more astonishing is Italian artivist Alfredo Meschi, who had forty thousand Xs tattooed all over his body (with vegan ink, of course) to symbolize the estimated number of animals killed for their flesh each second. He regularly posts photographs of his neck, arms, and torso on social media. “Yesterday was the first sunny and really warm day of spring in Tuscany,” he wrote in one Instagram caption. “For me, it starts the period of the year when I can openly mourn the loss of our animal companions. Through public performances, peaceful vigils, bearing witness, I will offer my body to people’s attention.” Meschi was inspired by Mexican artivists who paint their bodies to protest government collusion with drug cartels, but he felt compelled to create a more permanent statement. The choice to tattoo one’s skin is an act of creative agency, and Alfredo’s decision underscores the fact that factory-farmed animals don’t have any control over their own bodies.

Instagram is the ideal resource for discovering vegan artists from all over the world, and the #veganillustration hashtag is how I found Samantha Fung (@oneheartillustration) and Kate Louise Powell (@katelouisepowell)—young animal-rights artivists who present themselves with hair and makeup and clothing that is even more vibrant and colorful than their artwork. Posts of new work are interspersed with snapshots from animal-rights marches and community outreach projects. In making their physical appearance so remarkable, artists like Samantha and Kate ensure that you will also remember what they stand for.

Artists like these are often dismissed as attention seekers, but critics of animal-rights activists tend to search for any reason, logical or not, to invalidate the message in their own minds. On the contrary, writer and Our Hen House cofounder Jasmin Singer says that when we change our lives to include all animals within our circle of compassion, we naturally become less self-absorbed. For Singer, showing up for the animals means speaking candidly of the shame and self-loathing that come saddled with an eating disorder, and sharing how she’s grown into a woman who can present herself to the world as “thick and grabbable and real.” When you watch her TEDx speech, you have the impression of someone who has distilled the best of herself into her feminist animal-rights advocacy. Singer knows that we each need to grow into who we need to be in order to do as we are destined.

© Marinksy, Better Half, altered photograph, 2017.

@marinksy.paintings

Each of the artists I interview in part two put themselves and their work out into the world in a deliberate way in order to create this book. I wouldn’t have found most of them without social media. As for me, my first big step away from the antique wallpaper is in writing these words—as Jill Louise Busby writes, “Truth fights for itself. If you’re open to it, it will use you as a weapon”—though I know I’ll need to show up online and in real life to promote this book in a bigger way than ever before.

But I’m up for it. The animals need all the help they can get.