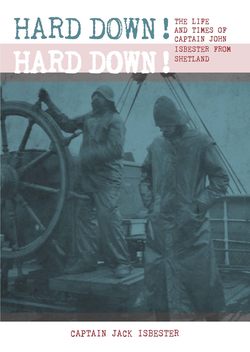

Читать книгу Hard down! Hard down! - Captain Jack Isbester - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1 CHILDHOOD IN SHETLAND

ОглавлениеOn the face of it my grandfather John Isbester could hardly have had a poorer start in life. He was born at Mailand, in South Whiteness, Shetland, on 9 February 1852 to Sarah Anderson, who was illiterate, and John Isbister, a seaman who left for the Antipodes without marrying Sarah and never returned. That my grandfather survived the further blow of his mother’s death when he was 15 to become a master in sail at the age of 32, to sail in command for 29 years, and to command for 13 years one of the largest three-masted square-rigged sailing ships flying the red ensign, is a testament to his character, ability and determination, as well as to his good fortune.

John Isbester’s first surviving words were not written until he was 32, but there is plenty of information about his family, and about his life and times, to help us to understand his background and early years.

Mailand was the home of the Anderson family, and at the time of the 1851 census the household consisted of Mary Anderson, aged 66, her sister-in-law Elizabeth, 73, and her son’s wife Catherine, 22, in addition to a farm servant, Christina Robieson, aged 20, and of course her daughter, Sarah, aged 20, who was to become my great-grandmother. Catherine’s husband, Laurence Anderson, was probably away at the fishing at the time of the census. The Andersons were a big family – my great-grandmother Sarah was the last of ten children – most of whom were born in Hogan, South Whiteness, and were by 1851 dispersed through Shetland and overseas. My grandfather’s Anderson uncles are variously described in census records as fishermen, seamen and whalers, and family tradition has it that he spent much of his childhood in the household of his uncle Laurence Anderson, a crofter and fisherman of Haggersta, Whiteness. There he was much closer than might be expected to his absent father’s side of the family, because his father’s younger sister, Catherine Gifford Isbister, had married Laurence Anderson in 1850. The Haggersta home of Laurence and Catherine Anderson seems to have been a real home to John Isbester. In later life he quoted it as his place of birth – perhaps he knew no better – and it was there in 1884 that he shared a bottle of whisky ‘with all the town of Haggersta’ at seven in the morning of his wedding day!1

Laurence and Catherine Anderson had moved from Mailand in the 1850s, most of their children being born in Haggersta, and my grandfather would have grown up in a household mainly of women. For Shetland this was very normal: the menfolk worked and often died at sea or overseas. Consequently there was at this time a marked population imbalance, with about nine women for every six men, a circumstance that made Shetland women capable and independent minded.2 Apart from his mother, Sarah, and his aunt, Catherine, there were her children, his cousins, Ann (a year his senior), Mary (three years his junior), Catherine (four years younger) and Robina (six years behind him). It wasn’t until he was ten that male cousins, in the form of Peter, Robert and Laurence, began to arrive. The man of the house, Laurence Anderson, was often away from home, the census only finding him in Whiteness twice in sixty years. The evidence of his children’s birth certificates is consistent with his being away from home for most of the summers, suggesting seasonal employment in the Shetland fishing industry, a very familiar pattern at that time.3

I rely on my father for the information that my grandfather spent most of his childhood at Haggersta and went to school in Whiteness, but there is confirmation of this from an interesting source. Writing in 1913 my grandfather describes meeting Bella Leask in Melbourne and reports ‘Bella minds a whole lot about me when we were at school that I had forgotten’.4 I think that this must be the Isabella Leask born in 1859, daughter of Arthur Leask, a merchant seaman who in 1871 was living in Hellister, Whiteness.5 The entire school, comprising the teacher with 59 children aged from 5 to 15 or 16, was housed in a single room6 but, as is so often the case, the results depended more upon the skill and enthusiasm of the teacher and the interest of the pupils than upon the pleasantness and comfort of the surroundings. John Isbester’s future career suggests that his schooling was more than adequate.

In 1857 or thereabouts, when he started school, my grandfather would have been taught by Robert Jamieson, whose letters were published in Shetland – a love story.7 Ten years later, when he left to go to the fishing, his teacher would have been David Hobart (Fig.1.1) who we will meet again as a teller of vivid stories and a friend of my grandmother’s family. Between Jamieson and Hobart came James Irvine and possibly other teachers. My father wrote ‘Mr Hobart was an excellent teacher of navigation – all the Whiteness boys benefited, my father included – and my mother’s Gifford cousins used to come from Busta to stay at Olligarth to get Mr Hobart’s teaching.’8 Shetland teachers who could teach navigation – a day’s work and perhaps a meridian altitude9 – were in demand by seafarers on leave because their prices were lower than those of the navigation teachers in the seaports.10 Schooling in Whiteness would have been interrupted from time to time for more immediate or, occasionally, more enjoyable matters. Few records from the 1860s remain but they were doubtless similar to later years when attendances were down when the peats were being cut or the crops harvested and when a half day was awarded for the nearby Whiteness and Weisdale regatta.11

The baptismal register for Tingwall, Whiteness and Weisdale shows that my grandfather was baptised in February 1854 as John Isbuster, son of John Isbuster seaman and of Sarah Anderson.12 The two-year delay in baptising him may have been partly due to his illegitimacy, although no baptisms were registered between December 1852 and January 1854. It seems unlikely that he suffered any serious prejudice as a child, embedded in a supportive family and with his father well known locally but absent overseas like so many other men from Shetland. Illegitimacy was rare in Shetland at this time, with a frequency of about 4 per cent compared with a frequency of 9 per cent throughout Scotland.13 It carried a stigma except when the couple were simply anticipating the wedding. John Isbister senior – my great-grandfather – eventually died aged 86 in Hokitika, New Zealand where he had lived, unmarried, for much of the final 50 years of his life.14

Figure 1.1 David Hobart, schoolmaster at Whiteness

The 1851 census in Shetland recorded the family name as Isbuster, but the 1861 census adopted the spelling Isbister for the same individuals – and in 1871 the enumerator decided on Isbester! In cases where people were unlettered the enumerators used their own judgement and different enumerators at different times reached different conclusions. My grandfather, at the age of 15, signed his mother’s death certificate boldly and clearly in 1867 as ‘John Isbester’, and that is the spelling of his name which he used for the remainder of his life. A belief within the Isbester family that my grandfather had chosen to change his name from Isbister to Isbester for unknown reasons seems to have been mistaken. While Isbister is by far the most common version of the name in Shetland it is clear that in the 1850s and 1860s the spelling was arbitrary. It seems likely that his schoolmaster decided the spelling to use.

My great-grandmother Sarah Anderson is variously described in official documents as ‘a knitter of shawls’ and ‘an agricultural labourer’,15 which doubtless reflects the life lived by crofters in the 19th century when a skill such as knitting shawls was a means of earning a few pennies to supplement a subsistence diet consisting of what could be grown or caught. She was, at the time of the 1861 census, living in South Hamarsland with her son John Isbister (sic) and his two-year-old half-sister Barbara Anderson, later known as Barbara Hunter. Barbara, like John, was illegitimate and her mother signed her birth certificate with a cross, identified by the registrar as ‘Sarah Anderson her mark’, a reminder that in the days before education became compulsory it was still common for poorer people to be unschooled. South Hamarsland is only 4 miles from Whiteness, but such is the nature of Shetland, with long fingers of sea penetrating the land, that Whiteness is on the West or Atlantic coast of Shetland while South Hamarsland, on the shore of Lax Firth in Tingwall, is on the East or North Sea coast.

Knitting shawls was, for Shetland women in the 19th century a very common activity. Shortly after Sarah Anderson’s death the Truck Report16 provided the results of the investigation into the barter system used in the Shetland shawl and hosiery industries and in the fishing industry during the years when John Isbester was growing up. The report contains some 17,000 questions put to more than 200 men and women about their lives and working conditions, and contains fascinating insights into the lives of Shetland folk in that period. The landlords and merchants who operated the barter system generally claimed that their tenants were treated fairly and reasonably and were not oppressed, while detached observers such as clergymen considered that the crofters were compelled to knit shawls and to go fishing in circumstances where, being usually in debt to the landlords and merchants, they had little alternative.

Women knitting shawls used wool from their own sheep which they spun themselves, or wool obtained from the merchants who bought their finished shawls. These beautiful, intricately patterned creations were about 2.5 yards (2.3 metres) square, and, if the wool had to be spun before the knitting the whole process of making a shawl took about four weeks of hard work. Clementina Greig17 of Scalloway, a woman with 33 years’ experience of knitting shawls, reported ‘When I spin the wool myself [making a shawl] it takes me a month, but with clean worsted I will make it in about three weeks,’ and when she was asked ‘How long will the spinning of half-a-pound [of wool] take?’ she replied, ‘It will take me a week to spin it sitting very close at it and sleeping very little.’

Euphemia Russell18 of Scalloway had knitted shawls for 25 years when she could sell them, and when she could not she worked ‘Sometimes in the fields and sometimes at the fish’ for about three months a year. Working at the fish would have been gutting herring or tending the cod spread to dry on the beaches for subsequent sale overseas.

Shawls usually sold for 17 shillings which would normally be paid entirely in the form of goods from the shop such as tea, sugar, bread, soap and cotton. The knitters preferred payment in cash, but this they say was normally refused except for the odd penny or two. They would accept more tea than they needed and would then exchange it with farmers for produce such as potatoes and meal. The possibility of selling a shawl for £1 cash direct to a summer visitor was a rare but welcome opportunity.

When asked ‘Have you often had to barter your goods for less than they were worth? ‘Mary Coutts19 of Scalloway replied:

Sometimes, if there had been 2½ yards of cotton lying [unused] and a peck of meal came in, we would give it for the meal. The cotton would be worth sixpence a yard, or 15 pence [in total] and the meal would be worth one shilling [12 pence]. I remember doing that about three years ago; but we frequently sold the goods for less than they had cost us in Lerwick.

To explain why spinning the necessary wool would take her more than a week, Mary Coutts said, ‘We have to go to the hill for our peats and turf, and that takes up part of our time,’ a reminder that the knitting of shawls was no alternative to housework, but just one more task.

It is not clear how long Sarah Anderson lived at South Hamarsland, but six years after the census she was again recorded in the same vicinity. On 4 July 1867 she died in the Garths of Easthouse, a stone-built dwelling with a single room, the ruins of which still stand about 200 metres from the ruins of South Hamarsland. Her death was untimely – she was only 37 – and terrible. The death certificate gives the cause of death as ‘Inflammation of the throat and lock-jaw’, otherwise known as tetanus. John Isbester was 15 at this time, and had already spent a summer at the herring fishing. He was home between cod-fishing voyages aboard the Faroe smacks. The death certificate records that he was present at her death and that she had no regular medical attendant.

His mother’s death and the manner of it must have been a traumatic experience for my grandfather, boy that he still was at the time. My father spoke often of my grandfather – he was proud of both of his parents – but I do not recall him ever mentioning his grandmother’s death, and it is possible that he never knew the details of this event, which had occurred more than 30 years before he was born.

So, what was Whiteness like in the 1850s when my grandfather was a boy? The crofters lived their lives at subsistence level:

It has been calculated that from 1780 to 1850 there was on average one famine year in every four and, although destitution did not reach the level of Ireland or the Western Isles in the 1840s, there were families who lived without oatmeal or bread for months on end. Fish proved to be their salvation.20

The census enumerator describes South Whiteness in 1851 as being

partly pastoral and partly agricultural … Soil mostly thin on limestone rock with a considerable portion of wild moor – precipitous towards sea shore – intersected by the voes [long, narrow arms of the sea] of Binniness and Whiteness … The inhabitants are industrious and chiefly employed in farming and in fishing and in those seasons that out of doors occupations cannot be carried on the men are engaged in repairing their boats, nets and fishing tackle – and the women in knitting hose, gloves, shawls etc.

J. O. Ross, the enumerator for North Whiteness, when describing the district as ‘Nearly divided into two distinct parts by a wild barren hill which has to be crossed east and west ere the Census could be taken making it a more difficult task to perform’, appears to be trying to justify his claim for expenses, or appealing for sympathy for the privations he had been forced to suffer in performance of his duties. He goes on to observe that

In the South part of the district agriculture is poorly attended to, in the North end of the district pasturage of sheep and cattle is more attended to than the proper tillage of the soil. The people tho’ poor and subjected to inclement weather and other casualties [attempt] by fishing and farming to provide in a measure for their families. For the past two or three seasons the potato failure so prevalent in these islands has reduced the people in circumstances and it will be some time ere they recov’d their position.21

It is fortunate that there were almost always fish in the sea. Every croft had its boat, and a few hours on the water would usually bring a catch, perhaps some herring, haddock, ling or cod.22

The neighbouring district of Weisdale was in 1851 described as ‘Wholly without formed roads, the surface hilly, abounding with marsh and moor, and the houses very widely scattered.’23 In these conditions in the 1850s and for many years thereafter, most journeys were made on foot or by boat. In Shetland one is never far from water and, particularly when less active people required transportation, the journey was usually by boat. David Hobart, schoolmaster in Whiteness for a number of years in the 1860s and 70s, provides a lively description of a trip mainly by boat from Busta to Whiteness in May 1868. Both boats mentioned would have been double-ended Shetland fourareens, about 23 feet in overall length, rowed by two or four oarsmen, each with one oar. At the helm was my maternal great-grandfather, Magnus Irvine of Strom Bridge,24 Whiteness, aged 45. The passenger was Margaret Irvine, his wife, aged 41. At the oars were David Hobart, aged 26, and Robbie Tulloch, aged 43, a live-in farm worker with the Irvine family. David Hobart lodged with the Irvine family and was in love with their elder daughter, Mary Jane, for whom this account was written.

After leaving you at Busta we kept close along the shore [see Fig.1.2] making fair progress, till we came to the opening of St Magnus Bay where, the wind having increased and the sea having more space to gather way, we could with some strokes urge forward the boat scarcely half her length, and with others barely hold our own. [The wind was probably south-west.] Mrs Irvine was for returning. Mr Irvine was for going. This opinion prevailed. There was no danger he said, except that of a long hard pull, and when the boat had made marked progress across, he further remarked that patience and perseverance – I didn’t hear the conclusion of that proverb. Then came a slight lull of which we took due advantage by rowing like galley slaves. This brought us under the lee of the island [Papa Little] and our next difficulty was to get round the point [Selie Ness] on which we nearly went aground last night. We had to go out into the middle of the voe under the full force of both wind and waves and as the wind was still increasing our strength as well as our patience and perseverance was tried to the utmost. The point was slowly passed. To rest was to go backwards. Another point was ahead under the shelter of which we could rest and take in more ballast. Every nerve was strained to reach it which we at last did. A drink of buttermilk, a smoke, a few stones put in [as ballast, to prevent the boat being caught too much by the wind] and we were off, & Busta which had hitherto been in sight and from which we thought you were watching us, was lost to view. The wind and sea were now worse than ever. Robbie sometimes let the head of the boat fall down & the spray would dash over us. [From this I deduce that Robbie and David were each rowing with one oar, with Robbie on the port side.] Once the whole top of the sea came in over the quarter right upon Mrs Irvine which nearly upset her equanimity. A short time after we again got under the lee of the shore and went about as fast as we did at first. Aith was reached about four hours after leaving Busta [a distance of about 7 statute miles]. My hands were the only thing that suffered damage.

Figure 1.2 Journey by boat and foot from Busta to Strom Bridge

A rest at Aith. No thought of another sea voyage. The [second] boat was to be left at Bixter, said Mrs Irvine and likewise Mr Irvine. Not being in command I didn’t give any opinion. Little said going over the hill. A little said going down the hill & that little was to take the boat to Tresta – nothing more. [Aith to Bixter had been a walk of 2.5 statute miles.] In to see Mrs Johnson – a biscuit and a dram. The wind had shifted two points to the west – get the boat down – the boat was got down – and rowed under the lee of the opposite side – the rudder shipped and down the voe as if running a race. Tresta was never looked at. Now we again met the wind and rowed easily along the lee of the shore till we came opposite the point of Russa Ness – Then along the side of the wind, the boat rolling over the large waves – the skipper was steering, Robbie and I rowing. The point was passed and then right before the wind to old Johnny Abernethy where we landed & drew up the boat. Home at last.

It appears that the boat was headed straight across Weisdale Voe to Haggersta in Whiteness, from where it was a walk of only 0.7 statute miles to home at Strom Bridge. This second boat trip would have been of about 6.5 statute miles.

Writing a few days later,25 David Hobart remarks that ‘The boat has not yet been brought round’, which I take as confirmation that the boat had been left at Haggersta or thereabouts and was to be brought down Weisdale Voe and up Stromness Voe, a trip of 7 miles, after which it would be half a mile closer to Strom Bridge.

A further example of a boat trip in the same period is recorded by another schoolmaster, Robert Jamieson, who by coincidence also taught at Whiteness. In November 1860, when he had left Whiteness and moved to Sandness, he visited his beloved in Gulberwick. He was lame and was loaned a horse for the journey home but was forced to leave it at Cova. He records26 that he went to Clousta and took a boat from there to Sandness, a distance of 12 miles.

I had to bribe the lazy fellow of a boatman with extra fare before I could make him move. He thought it so cold and a part of the voe was frozen.

When love drove him, David Hobart was prepared to walk as well as to row. One weekend when Mary Jane Irvine was at Busta, he proposed leaving Strom Bridge at 0400 hrs, reaching Busta at 0900 hrs, leaving Busta at 1700 hrs and arriving back at Strom Bridge at 2200 hrs.27 The distance, over rough open countryside with few tracks, is about 16.5 statute miles each way. In the event he made the return journey to Strom Bridge on Monday morning, leaving Busta at 0310 hrs and reaching Strom Bridge at 0810 hrs, ready for a day in school. When enjoying the simmer dim (twilight) of late June in Shetland this was a practical proposition.

This is his account:28

On leaving you I set out not very fast but gradually my pace quickened till I went at full swing. One hour and three quarters I was passing Voe where I found innumerable fences and dykes the gates of which I never took the trouble of looking for but climbed or vaulted over them as they came in my way. Hunger also made itself felt there & I sat down and ate a piece of bread & took a good draught of water out of a spring. Then into the lee side of a dyke to smoke which detained me about twenty minutes. For the next hour & quarter I was passing between Voe and Setter plunging through mires, over bogs, leaping ditches and vaulting wire fences. Setter was reached at last. Mr M in bed not so much as whiff of tobacco and drink of milk – stingy dogs – said I. Though breakfast was offered – Breakfast took up time & time was everything to me. I found a kinder but less able entertainer in Malley of the Lea – Her tea was not ready – her cow was not calved a cup of cold water more of Mr Gs bread and butter & I was on the road again arriving in the dining room or sitting room of Strom Bridge ten minutes past eight, thus being with all my halts five hours exactly on the road.

With the leaping of ditches and the vaulting of wire fences, he sounds like a young man spurred on by love. Tragically Mary Jane Irvine, the object of his affections, died of consumption in 1870 aged 20, but her younger sister, Susie, has a major role to play in this story.

1 Isbester, Capt. John, letter J1 of 10.04.1884 (Isbester Collection).

2 Abrams, Lynn. Myth and Materiality in a Womans World. Manchester University Press, 2005. p.66.

3 Eight of Laurence Andersons nine children were conceived between September and March and he was at home between September and March to register four of their births. He was also home once in June to conceive a child and three times in June to register the birth of a child. I have found no evidence that he was ever at home in April, May, July or August which fits well with the pattern of summer fishing on the Faroe smacks (See Chapter 3).

4 Isbester, Capt. John, letter J26 of 06.04.1913 (Isbester Collection).

5 Shetland Islands Census 1871, District WW2.

6 Hobart, David, letter H6 of 03.06.1868 (Isbester Collection).

7 Jamieson, Robert. Shetland – A Love Story, The Shetland Times Ltd. Lerwick, 2010.

8 Isbester, Allan, letter CAI1 of 07.09.1966 (Isbester Collection).

9 Thomson, Captain J P OBE ExC. Captain John Isbester’s Career at Sea, Unpublished manuscript. 1971 (Isbester Collection).

10 Smith, Davie, letter DS3 of June 2013 (Isbester Collection).

11 Whiteness School Log Book, 1890–1912, Shetland Archive.

12 Baptismal Register for Tingwall, Whiteness and Weisdale. The Registrar, Shetland Islands Council.

13 Abrams, Lynn. Op.cit. P.154.

14 Isbister, John, Death Certificate, N.Z.No.1911008433, registered 27.10.1911.

15 Anderson, Sarah. Death certificate 04.07.1867 and the 1861 census.

16 The Second Shetland Truck System Report 1872.

17 Truck System Report Paragraph 11,527 et seq.

18 Truck System Report Paragraph 11,562 et seq.

19 Truck System Report Paragraph 11,585 et seq.

20 Thompson, Paul, Living the Fishing, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1981. p.313.

21 Shetland Islands Census 1851, District TWW 8.

22 Hobart, David, letters H8 dated 12.06.1868 and H10 dated 20.06.1868 (Isbester Collection).

23 Shetland Islands Census 1851, District TWW 8.

24 Strom Bridge, Whiteness, my grandmother’s family home, later known as Olligarth.

25 Hobart, David, letter H6 dated 03.06.1868 (Isbester Collection).

26 Jamieson, Robert. Op.cit. p.72.

27 Hobart, David, letter H11 dated 23.06.1868 (Isbester Collection).

28 Hobart, David, letter H12 dated 29.06.1868 (Isbester Collection).