Читать книгу Hard down! Hard down! - Captain Jack Isbester - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

3 EARLY YEARS AT THE FISHING

ОглавлениеFamily tradition has it that my grandfather started his seafaring career at the Shetland herring fishing in 1866, when he was aged 14. Herring fishing was a summer activity, with the shoals being found to the west of Shetland in May and June before moving east of Shetland in July and August. In Whiteness, as elsewhere in Shetland in the 1860s, fishing was a major activity – there were 363 boats and about 1,500 men and boys employed in the Shetland herring fisheries in 1859, and 17 ship or sloop masters lived in the parishes of Tingwall, Whiteness and Weisdale.1

It is not difficult to guess John Isbester’s motives for turning to a life at sea. Captain Thomson of Sandness in Shetland was writing about my grandfather, but was drawing on his own experience of growing up in the same vicinity a few years later, when he wrote2

Haggersta was his early lookout station and the mouth of Weisdale Voe with its islands and the great ocean beyond, was the panorama before him. Every croft around the voe had its noost [place where a boat could be drawn out of the water] with one or more boats according to the family requirements, for fishing, travelling and inter island transit. In addition there were schooners, smacks and herring boats making their way to and from distant waters in search of those denizens of the deep, the cod and herring.

In the 1860s much of the Shetland fishing was done from open boats, sixareens, fourareens or quilleys. The sixareens, used in most parts of Shetland were double-ended boats about 10 metres in length overall with a crew of six. They were alternatively known as sixearns, the spelling and pronunciation varying from one part of Shetland to another. The fourareens, about 7 metres long, were used on the southern part of the west coast of Shetland, including Whiteness, where they were better suited to the local harbours and beaches. The sixareens were used for what was known as the ‘Haaf’ fishing, for cod and ling, up to 40 miles offshore in boats that might be at sea for up to three days. The fourareens were fished up to about 15 miles from land, while the quilleys, about 5 metres in overall length, were used by the old men and boys for inshore fishing for herring, whiting, haddock and shellfish.3 In 1869, when registration of open fishing boats was first required, there were 15 fourareens spread amongst the various Whiteness crofts, each with a crew of three or four men.4 The Whiteness boats were owned by the crofters themselves, unlike in some other parts of Shetland where the landlords owned them.5 However no fourareen was registered for John Isbester’s home at Haggersta. This supports the suggestion that his uncle, Laurence Anderson, used to go each summer with the Faroe smacks.

There would be plenty of opportunities for a local boy to find employment fishing in Shetland. In the 1860s herring fishing, like cod fishing, was often done from sixareens. John Isbester probably sailed with a sixareen from Lerwick. The sixareens were more suitable for cod fishing than for herring. For the former about six miles of line were used. This took up less space in the boat than did the six or eight nets6 required for herring. Consequently the cod-fishing gear left more room for the catch,7 a very important consideration. In the 1860s the herring fishermen fished up to about 15 miles from the coast8 and landed the catch for curing. The relevance of John Isbester’s experience of sailing in sixareens will come to mind when reading the account of the loss of the barque Centaur, 30 years later and the subsequent eight-day voyage by boat to the Hawaiian Islands.9

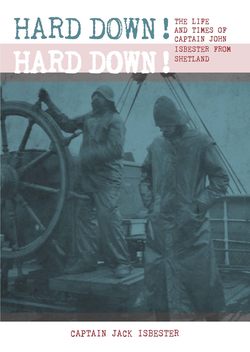

Figure 3.1 Sixareen at Unst Boat Haven, Shetland

The history of the sixareens, their construction, their use and the exploits of their crews are cherished in Shetland, with justified pride in the traditions, skill, ingenuity, courage and endurance with which they were used (Fig. 3.1). There is a Shetland name for every part and fitting of the boat, and the names hark back to their Norwegian roots. The sixareens were usually assembled in Shetland from timber imported from Norway or Scotland.10 When fishing, they were equipped for trips of up to three days. They were propelled by up to six oars with each man taking one oar, or by an almost square sail set on a yard on a mast stepped just forward of the centre of the boat. They were small – usually 9–11 metres in length overall – and every scrap of space was used. Sixareens were divided into seven working sections by six thwartship rowing benches with vertical gratings beneath them.11 The aftermost section was for the helmsman with his compass, steering with rudder and tiller when the boat was sailing. The next section could be divided with a broad shifting board, aligned fore and aft, and accommodated the catch of fish or, on the outward journey, part of the ballast – up to a ton of beach boulders – to be thrown overboard when fish were caught. Next came the section devoted to bailing. In heavy weather the boat would ship quantities of spray and quite often breaking seas, and it was the job of the bailer, equipped with a bailing shovel which could contain up to 9 litres of water, to get rid of the water before the next sea broke over the boat!

The next section, in the middle of the sixareen, was used for shooting and hauling the fishing lines when fishing for cod and ling, or the nets when fishing for herring. The mast was stepped through the thwart immediately forward of the mid-section. Forward of the mast was space for most of the ballast and for the fire kettle, the pot and the peat fuel. The fire kettle was a large earthenware jar containing burning peat, kept lit throughout the voyage, over which a pot of food or drink could be heated. The next section contained the sea chest, a heavy box, its lid covered with a tarpaulin, containing provisions and utensils.

Finally, in the bows were stowed two water breakers, or containers, and the sail when not in use.

The sailing of a sixareen in heavy weather has been described in several Shetland books12,13 with particular reference to the terrible storm of July 1881 in which ten sixareens and 58 men were lost. A survivor14 published a gripping account15 of how, when the wind struck from north by east with little warning, three miles of fishing line were cut and abandoned, the close-reefed square sail was set and the helmsman set the boat running south east through heavy-breaking seas for the trip of some 37 miles to sheltered waters or, if they got it wrong, to founder in the stormy seas or to wreck on the unforgiving rocky coastline. The tack of the sail had been set forward, effectively making it a fore and aft sail, and two men took the halyards. What is particularly fascinating about this account is that the boat’s speed was varied, to avoid the worst of the breaking crests and, when surfing, to keep on top of the wave, by the combined efforts of the three men who controlled the sail – the helmsman with the sheet and his two companions on the halyards. A version of this technique, called ‘pumping the sail’ by yachtsmen could be seen on television in use by the Finn class yachtsmen at the 2012 Olympics. Even in the later stages, as they reached more sheltered waters, the sixareen crew had, as the boat pitched forward over a roller, to ‘keep the sail low, and ease,’ to avoid the bow being forced below the surface. There is no suggestion that John Isbester experienced conditions quite like those described above but he may have done so, and in a season of fishing in the stormy Shetland waters he would undoubtedly have met periods of nasty weather and had the opportunity to improve his boat handling skills by observing his experienced companions.

Following the 1866 season of some four months which John Isbester spent at the herring fishing, he joined the smack Telegraph on 1 April 1867.16 Aged just 15, he joined as ordinary seaman (OS). She was single-masted – a long-boomer – with an enormous sail area for her size, having been built in Barking, Essex, to run fish from the Dogger Bank to the Billingsgate fish market.17 She was over 70 feet (22 metres) in length and her main boom extended 13 feet (4 metres) over the taffrail.

The 1860s and 70s were a prosperous time for the Shetland cod fisheries in which Telegraph, like other Faroe smacks, was employed, and John Isbester had probably signed an agreement earlier in the year which required him to be ready to join on 1 April for the first of three fishing trips of six weeks or thereabouts to Faroe, Iceland or Rockall. Scalloway, the west coast Shetland seaport near Whiteness, remained the main centre where smacks were cleared by Customs, took on crew and loaded provisions.18 John would have invested in the essential knee-high leather boots, the oilskin trousers and jacket, the personal fishing line and hooks plus meagre provisions, all bought from the owners’ store against an advance taken from his anticipated share in the profits of the voyage.19

For several days he and his dozen or so shipmates would have been employed in the hectic work of storing the ship, taking aboard perhaps 30 tons of salt for curing the catch, sacks or barrels of yeog (horse mussels) for bait, provisions and fresh water, several tons of coal for the stoves, fishing gear, fish handling gear and spare sails and cordage.20 John Isbester would have had a good idea of what to expect. About 80 Faroe smacks were in service at that time21 and hundreds of Shetland men and boys served aboard them. Family, friends and neighbours could recount their experiences, and he would have been in no doubt as to the challenges that could face him in a life that was reputed to sort the men from the boys. The cod fishing was very hard work, and the crews were predominantly young men in their teens, twenties and thirties.

When they put to sea their most likely destination would have been Faroe. Rockall was unpopular, as being an isolated rock it was more difficult to find and because no supplies of fresh water and bait were available there if needed. In addition, when fishing at Rockall, a smack had nowhere to run for shelter. By contrast, at Faroe and Iceland it was usually fairly easy to find shelter in the various fjords and bays if weather conditions became too severe to remain on the fishing grounds.22 Icelandic waters tended to be ice-infested until later in the year and were, therefore, most likely to be the destination for the final voyage of the season. The Faroe smacks relied entirely upon sail, and the voyage from Shetland to Faroe could take anything from two days to two weeks.

On his first voyage John Isbester would have had to become used to a four-on/four-off watchkeeping system during which he would be trimming sails, steering, keeping lookout, tending the galley stove and doing whatever other tasks were given to the most junior hands, while coping with the cold, the smells and the inevitable violent motions of the ship. All the crew slept in a single cabin, with two tiers of bunks and a central stove. When the fishing grounds were reached the crew changed to a three-watch system with, if fish were found, two watches always on duty and one watch off, so that each man was fishing for 16 hours a day. The only exception was on Sundays when no fishing was done, and the skippers took the opportunity to close with other smacks and get news of what success they had had with the fishing.

Captain Thomson23 wrote:

Upon arrival on the fishing banks which were found usually by dead reckoning and the hand lead, sails were balanced to suit the speed required. The fore sheet was hauled hard to windward, the main boom run off and the helm was put hard-down. In this condition the vessel backed and filled, keeping the station fairly well – raching it was called. The hands line the rails, shoot their lines and the vital operation begins, sometimes with little success but the crew toil on, balancing on the slippery deck to the roll and pitch of the vessel.

The cod would be swimming at some level between the surface and the sea bed (at depths up to 165 metres when off Faroe) and would be caught with weighted lines, each armed with two baited hooks. The on-duty crew, including the captain and mate, would be distributed along the weather side of the deck, where leeway would ensure that the ship did not drift over the lines, facing into the wind, each lowering his line into the sea and, when the cod were there, quickly pulling the line back up with one or often two cod hooked on, each weighing something like 14 kg. Once the cod had been brought on deck and unhooked the hooks had to be rebaited and the line with its 3 kg weight lowered back into the sea. If an icy, spume-laced wind was blowing, as it usually was, and the decks were slippery with water and fish, as they usually were, this work became all the more painful, arduous and exhausting. It is difficult to imagine the sheer effort required to haul the heavy weight of struggling fish from the depths time after time and hour after hour with aching and exhausted limbs and with hands chilled, lacerated and stung by salt. Crew members were liable to be fined if they failed to turn-to or if they were considered to be slacking, but they did have an incentive to do their best. Individuals were required to keep a record of the fish they caught, which they did by cutting off and retaining the barbel – the whisker-like organ that hangs below the lower jaw of a cod – to provide the proof. They received a bonus payment, usually sixpence, for each score (20) of fish caught.24

When the fishing was really good it was a case of all hands on deck, working round the clock, perhaps catching 1,000 fish a day and only stopping when the shoal disappeared, the weather became foul or there was so much fish on deck that they had to stop fishing and process it.25

Processing the fish involved installing the flensing table on deck, then removing the head of each fish, gutting it, splitting it, removing its spine, washing and scrubbing it free of all blood and gut lining, salting it and stowing it in the hold. Junior hands like John Isbester were expected to do the beheading, gutting, washing and scrubbing, salting and stowing, but the splitting and removing of the spine was skilled work usually done by the master, mate, or trusted senior hand.

When the fishing was poor the cold wind seemed even keener, the icy spray more hostile and the slippery, pitching decks more treacherous. As Captain Thomson observed,26 ‘This was indeed an endurance test to make or break, yet many young Shetlanders started their sea career under these conditions.’

To sustain them, the crew were provided with ‘biscuit’ (actually bread) and with coffee which could be laced with brandy. They could also eat fish. The Shetland practice of eating cod livers, a natural source of vitamins A and D, was a healthy one which helped to prevent illness during long periods at sea. Any other food they had to provide for themselves.

There was one bonus to work on the Faroe smacks – the smuggling of duty free brandy and tobacco from Faroe, and there are reasons to believe that for much of the 19th century 80–90 per cent of the Shetland population was involved in the trade, as either smugglers or their customers. With the Shetland fishermen knowing every inch of the coastline and the Customs officers all coming from England or Scotland, it was common practice for the contraband to be landed at night in some remote spot before the smack made a public arrival in port on the following morning.27 On his first voyage John Isbester might not have had any money with which to buy contraband, but in the next three years he would have many further opportunities.

John Isbester paid off the Telegraph on 10 June 1867 and was at his mother’s home, Garths of Easthouse in Tingwall, when she died from tetanus on 4 July that year. We know nothing of her death except for the bald facts recorded in the death certificate.

John Isbester had a half-sister, Barbara Anderson, who like him was illegitimate. At the time of her mother’s death she was a few days short of her eighth birthday, and her future must have concerned John and members of his extended family. From census records it appears that his aunt Philophia (or Philadelphia) Sutherland, his mother’s eldest sister, took Barbara into her own family. The census of 1871 describes Barbara as a scholar (ie a schoolchild) and annuitant and gives her the surname Hunter, which hints that the previously unadmitted father had played a role in providing for her future. That John Isbester kept in contact with his sister through the years is evidenced by a postcard,28 couched in affectionate terms, from Barbara’s daughter Susan, writing in 1913. She writes ‘We were all so glad to see that uncle had arrived safe and well’, apparently referring to his final successful passage from Newcastle NSW to Callao, Peru.

With his own career at sea launched, his mother dead, his father incommunicado in New Zealand and his half-sister provided for, John Isbester had every reason to return to sea and he did so by joining the schooner Novice, another Faroe smack, on 9 August 1867 for her final trip of the season, ending on 30 September.

1 Zetland Directory & Guide Second Edition.1861.

2 Thomson, Captain J.P, OBE ExC. Captain John Isbester’s Career at Sea, p.2. Unpublished manuscript. (Isbester Collection).

3 Smith, Davie. Personal letters Nos.DS5, DS9 (Isbester Collection).

4 The Shetland Customs and Excise Fishing Boat Register for 1869, Shetland Archives, Lerwick.

5 Smith, Davie. Personal letters No.DS5 (Isbester Collection).

6 The Shetland Book, Zetland Education Committee, 1967, p.89.

7 Halcrow, Captain A. The Sail Fishermen of Shetland. The Shetland Times Ltd, Lerwick, 1994. pp.82–83

8 Coull, Dr J.R. Herring Fishing in Scotland, A Resources for Learning in Scotland Project.

9 See this book, Chapter 11.

10 Halcrow, Captain A. Op.cit, pp.67–68.

11 Halcrow, Captain A. Ibid, pp. 69–71.

12 Sandison, Charles. The Sixareen and her Racing Descendants, pp.16–17. The Shetland Times Ltd, Lerwick. 2005.

13 Halcrow, Captain A. Op.cit, pp.75–80.

14 Johnson, Charles, of Toam, North Roe.

15 Mansons Shetland Almanac & Directory for 1932.

16 Thomson, Captain J.P, OBE ExC. Letters JPT9, JPT10 & JPT11 of 1969. (Isbester Collection). For the dates of this and subsequent voyages prior to John Isbester obtaining command I rely upon unpublished research undertaken in the 1960s. Captain Thomson writes that the information on John Isbester’s early voyages on the smacks came from Mr Manson of the Shetland News while data for the subsequent voyages was obtained from the Registrar General of Shipping and Seamen at that time.

17 Halcrow, Captain A. Op.cit. p.105.

18 Goodlad, John, PhD. Thesis: The Shetland Cod Fishery from 1811 to 1908. A study in Historical Geography, Section 5.2.4.

19 Thomson, Captain J.P, OBE ExC. Op.cit, p.2.

20 Halcrow, Captain A. Op.cit. p.99.

21 Scottish Fishery Board Records quoted by Goodlad, John, PhD. Op.cit, Section 5.2.4.

22 Goodlad, John, PhD. Thesis: Op.cit. Section 7.1.3.

23 Thomson, Captain J.P, OBE ExC. Op.cit, p.2.

24 Goodlad, John, PhD. Thesis: Op.cit. Section 9.1.2.

25 Halcrow, Captain A. Op.cit. p.101.

26 Thomson, Captain J.P, OBE ExC. Op.cit, p.2.

27 Goodlad, John, PhD. Thesis: Op.cit Section 9.1.4.

28 Postcard No.26 to Mrs. Isbester ‘from your loving niece Susie’. (Isbester Collection).