Читать книгу Hard down! Hard down! - Captain Jack Isbester - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

5 SERVICE AS AN OFFICER

ОглавлениеAt the end of his voyage to Australia John Isbester, Able Seaman, paid off in Liverpool on 18 August 1876 and seven weeks later, on 3 October 1876, aged 24, he was awarded his second mate’s certificate of competency, no. 02269. He must have enjoyed an enormous feeling of satisfaction at the achieving of his first ambition. Captain R.S. Cogle, writing nearly 40 years later at the time of John Isbester’s untimely death, wrote under the heading The Loss of the Dalgonar:

Sir,- it was with a sad heart that I read the log of the above in the Shetland Times of last week. It has been my privilege to have known the late Captain Isbester for about forty years. He passed all his Board of Trade examinations under my guidance and never failed once.1

Captain Cogle was a Shetland man who ran a private navigation school at 35 Pitt Street in Liverpool and, in retirement, lived in Hoylake on the Wirral coast, just a few miles away.

It was not until six months later, in April 1877, that John Isbester returned to sea with an appointment as second mate. It appears that he had taken a voluntary winter holiday in Shetland – in 1884 he was described as having been ‘seven years south’,2 i.e. away from Shetland for seven years – which fits with what we know of his movements. Winter in Shetland would seem like a second best when there was an officer’s job to be enjoyed, and sunlit seas, gentle breezes and graceful palm trees to be found. It may well be that jobs were hard to come by, as they certainly were two years later, or he may have decided that he had earned a break and wanted to do a bit of courting. This appears to have been the time when John Isbester ‘left his watch’ (a Shetland expression for an informal betrothal) with Maggie Smith of Strome in Whiteness, the village of his birth. John Isbester eventually joined the wooden ship Nelson, of 943 tons gross, in Maryport as second mate. She was bound for Quebec, where she spent a month discharging and loading, and was back in Ayr at the end of June to end a round trip of two and a half months. Ten days later he rejoined the Nelson in Greenock for another trip to Quebec, this time under a different master. The fact that he was prepared to travel to Maryport and to Greenock to join the ship hints at an eagerness to grab a berth on a good ship – or perhaps on any ship from a shrinking choice.

A month after leaving the Nelson in Gravesend at the end of the second voyage, John Isbester joined the iron barque Parthia, 1,063 tons gross, in Liverpool for a voyage to Valparaiso in Chile, where, after discharging they sailed north to visit Iquique and load nitrate in Antofagasta, thence to Falmouth for orders and on to Liverpool. That voyage, with its rounding of Cape Horn in both directions, took 11 months and should have convinced John Isbester, if he needed convincing, that he had a good knowledge of the work of a second mate in square-rigged sail.

Back in Liverpool in October 1878, John Isbester found that there were no second mates’ jobs to be found, and on 12 November he took a decision that could have been life changing – he enrolled in the Liverpool Constabulary as a third class constable.3 Enrolling in the same period were men with such Shetland-sounding names as John Gifford Inkster, Peter Anderson, Hector Bain, John Irvine and Magnus Irvine, so it may have been the ‘thing to do’ at that time.

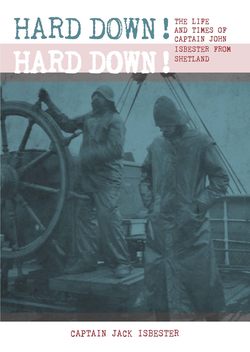

Figure 5.1 John Isbester as a young man

Photos of John Isbester (Fig.5.1) suggest that he was a man of good stature, probably a requirement for the police force. It would be good to believe that he enjoyed duty attending the crowds visiting the Walker Art Gallery, where up to four constables were posted, but it is more likely that his main concern was in dealing with the cases of drunkenness in Liverpool, which had in December 1876 risen from 15,763 to 16,859 per annum, leading to protests from prominent members of the public, insisting that the licencing laws be enforced.4 Other incidents requiring the attention of constables included dealing with the boys troubling Mrs McMillan in Balm Street and the need to apprehend Aaron Lipwitz, charged with stealing Abm. Liebenchutz’s cash box. I have found no record of when, why or how John Isbester left the Liverpool Constabulary, but he used to tell his family that he had been a policeman for about six months, which would place his departure from the Force during the summer of 1879. He finally returned to sea on 1 February 1880, joining the iron barque Cumeria, 1,336 tons gross, in Liverpool as second mate for a voyage to San Francisco. She had unrecorded problems which caused her to return to Liverpool after a day at sea, but she eventually completed the 11-month voyage with its double wintertime rounding of Cape Horn, returning to Hull to discharge her homeward cargo. That had been John Isbester’s first visit to San Francisco, a two-and-a-half-month stay in a port to which he was to return many times in later years. After four weeks’ leave John Isbester rejoined the Cumeria in North Shields for a voyage to Bombay with a cargo of coal. He must have done well on his first voyage on Cumeria because although the new crew signed on in Hull on 14 January his place was kept open for him to rejoin on 29 January.

Bombay would be yet another new destination for him, but the voyage would leave its marks on him for quite a different reason. When he came on watch at 0800 on 7 February Cumeria was south of St Catherine’s Point on the Isle of Wight and close hauled on the port tack, steering about south-west by west5 (Fig.5.2). The wind, from the south-south-east or south by east, was getting up, and there was a heavy cross sea from the west. Cumeria was carrying courses and upper and lower topsails in addition to jib, foretopmast staysail, maintopmast staysail and crojack, and Captain Evan Williams from Aberdovey ordered all hands on deck to shorten sail (Fig.5.3). John Isbester and his watch were allotted the mainmast, the hands going aloft to reef the main course and upper topsail while the mate and his watch reefed the corresponding sails on the foremast. Next John Isbester and his watch commenced furling the crojack on the mizzen mast while chief mate Gilbert Pearson from Shetland, bosun Robert Lloyd from Baltimore and four hands went forward to hand and stow the jib. The men selected were John Dodds from North Shields, John Small from Dundee, John Caygill from Whitby and Konstantine Barintizous from Italy. Captain Williams instructed them to wait for his signal before going on to the jibboom, the light extension to the bowsprit.

Figure 5.2 Barque Cumeria – tragic loss of four men

Figure 5.3 Cumeria before and after shortening sail

He then ordered Able Seaman E.G. (Johnny) Johansson from Sweden, the man at the wheel, to bring the ship’s head to starboard to steer WNW, bringing the wind abaft the beam, so that Cumeria was running free on the port tack, easing the weight on the jib and reducing the extent to which the vessel was pitching into the heavy seas from the west. This action made it safer for the men to go onto the jibboom, and when Cumeria was settled on the new course Captain Williams waved to the men to loose the halyards and go onto the jibboom to hand and stow the jib. When they were so engaged Captain Williams saw for the first time, at a distance of about 1½ miles, a sailing vessel which he judged to be on a collision course crossing on the starboard tack. Captain Williams was required by the Rule of the Road to keep out of the way of the other vessel, and to do this he would have to alter course to port, returning towards the more hazardous course so recently abandoned. Standing at the fore end of the poop, he waved to the men on the jibboom to get back inboard immediately, but they did not notice his signals, the bows being about 60 yards/metres from the poop. He waited as long as he dared, then ordered the helmsman to make a two-point alteration of course, to steer west, in order to avoid collision with the other vessel.

As Cumeria came onto the new course the foretopmast staysail sheet carried away (i.e. broke), and the vessel, now with sails unbalanced, broached to (i.e. lurched heavily, in this case with the bow swinging rapidly to port), and a heavy sea struck the port bow and swept over the jibboom, the bowsprit and the forecastle. At that instant the four men were swept from the jibboom into the cold February waters of the Channel, and the chief mate and bosun, on the forecastle, were trapped, reportedly ‘under the port tack’.6 The cry ‘Man overboard!’ was heard, lifebuoys and ropes were flung overboard and the yards were braced to port, to back the sails and stop the ship. One man in the water managed to catch hold of the mizzen vang, and another clutched the patent log line, but the vessel was at that time still travelling quite fast through the water, perhaps 6 or 7 knots, and agonisingly they were unable to retain their grip.

John Isbester was sent aloft to keep a lookout for the four men in the water, but could see none of them. Captain Williams asked for volunteers to man a boat, but none was prepared to venture, one man saying that if any of the men overboard were still in sight he would have been prepared to go. Captain Williams sailed back and forth through the area of the loss for the next four hours, but then, having seen nothing, resumed the voyage, and called at Falmouth six days later to pay off Johann Baer, AB from Danzig (Gdansk) and Per Rudolf Malmqvist, ship’s boy aged 17 from Sweden and to sign six replacements – five ABs and one OS. The leavers were, presumably, unwilling to continue the voyage after the distressing experience of the first ten days.

The official log book was reported to contain an entry, signed by four ABs including Johansson, the man who had been at the wheel, to the effect that the loss of the four men had been an accident and that every effort had been made to save them.

That the foregoing traumatic events are on record is because a letter signed by H.B. Johnson and dated 26 October 1881 was subsequently received by the Board of Trade alleging that the deaths of the four men were the result of ‘A piece of wilful carelessness and unseamanlike piece of work amounting to manslaughter.’ A formal investigation was held at Westminster in December 1881, the voyage having ended at Gravesend in mid-November following discharge in Rotterdam of a homeward cargo from Bombay. Six witnesses were present at the hearing, one being Captain Williams, and another the cook who confirmed the captain’s evidence that another sailing vessel had been nearby. It is likely that John Isbester was present too. He was in the UK at the time, on leave or studying for his first mate’s certificate, which he passed in Liverpool on 18 January 1882. One man not present was bosun Robert Lloyd: he had been left behind in jail in Bombay for reasons not recorded.7 The investigation cleared Captain Williams of any blame, concluding that the broaching-to of the vessel, which increased the severity of the heavy sea striking the port bow, was itself caused by the giving way of the foretopmast staysail sheet and was the cause of the loss of the lives in question. They further concluded that proper and seamanlike measures had been taken to stow the jib and that, Cumeria being the give-way vessel, Captain Williams had acted reasonably and safely when altering course two points to port to avoid collision. It was also concluded that every possible effort had been made to save the lives of the men. The tribunal decided that the complainant was the man who had signed Articles as John Johnson (sic),8 the AB at the wheel at the time of the occurrence, now again away at sea in the Mediterranean, and that his motive for making the complaint was that Captain Williams had refused to pay him off in Bombay where he had had the opportunity to obtain a more attractive job as cook and baker on a steam ship. They considered that, as one of the ABs who had signed the log book entry to the effect that the deaths had been accidental and that every effort had been made to save the men in the water he would, if present at the hearing, have found it difficult to justify his accusation.

So what might John Isbester have learnt from these tragic events? That a mariner’s life was perilous and could be snatched away in an instant was obvious, and he had seen that previously. He might have wondered why the foretopmast staysail sheet had failed so disastrously and why the master had not sent someone forward to warn the men on the jibboom of the planned manoeuvre. He might have reflected on how easy it is to lose sight of a lifebuoy or a man’s head in a rough sea, even at 200 yards/metres. The court hearing could not fail to show him the desirability of having a statement of events entered in the official log book and signed by witnesses who could be assumed to be impartial. It would also have shown him that allegations made but not supported by a witness in court were liable to be given short shrift, and the worst of motives attributed to the absentee.

Within a fortnight of obtaining his first mate’s certificate John Isbester was back at sea as chief mate of the iron-hulled ship West Ridge, 1,496 tons gross, embarked on a 15-month voyage first to Calcutta, which they reached in May after three and a half months at sea, benefitting from the south-west monsoon in the final Indian Ocean stages of the passage. That same south-west monsoon became their enemy a month later when, having discharged their cargo, they cleared for Liverpool on 20 June. Fighting their way out of the Bay of Bengal against the strength of the monsoon would have been a difficult, perhaps impossible, task, and the master appears to have had second thoughts or new instructions. West Ridge remained in Calcutta until the monsoon weakened in September, when they sailed for the lovely Indian Ocean island of Mauritius. Port Louis, the capital city and port of Mauritius, with its benign tropical climate, its gentle winds, blue seas, graceful palm trees and background of spectacular mountains, would have been a welcome contrast to the flatlands of sweaty, monsoon-drenched Calcutta. The Mauritian coconuts, bananas, grapefruit, oranges, limes, papayas, sugarcane, pineapples and guavas, available for the smallest coin would have been very welcome, there were lots of fish to be pulled from the waters of the harbour, and piglets and chickens might also have been available at a price. John Isbester might have noticed an intriguing similarity to his home port of Lerwick. In Port Louis he would see Arab dhows and Chinese junks alongside European square riggers and steamers just as in Lerwick he would see fishing boats from the Netherlands and Poland, from Portugal and St Petersburg as well as from England and Scotland. Both Lerwick and Port Louis are excellent sheltered ports situated at ocean crossroads.

West Ridge remained in Port Louis for two months before returning to Calcutta and finally back to Liverpool after making landfalls at St Helena and Ascension. On their homeward voyage they may have carried sensitive cargoes such as tea, coconut and tobacco. It is more likely that their cargoes were at the contaminating end of the spectrum – hides, horns and hoofs, crushed bones, myrabolams and amotto seed – along with neutral cargoes such as palm fibre, gunnies, hemp, and rope cuttings, as befitted slower and older ships, compelled to round the Cape of Good Hope rather than use the Suez Canal like the steamers.9

John Isbester, aged 31, now had the necessary seatime to sit for his Master’s Certificate, which he did following a few weeks at Captain Cogle’s school. On 7 August 1883 he was awarded Square Rigged Certificate No.02269. He must have felt joyful when he reflected that his years of hardship and sacrifice had earned him the reward for which he had worked with such commitment. All that remained was to obtain a command – and, perhaps, a wife.

But with no commands immediately on offer John Isbester decided that he had no choice but to do another voyage or two as chief mate. Within a month he had joined the wooden barque Queen of Australia, 1,328 tons gross, as chief mate for a voyage to Quebec. His experience would doubtless have been enriched by the events of the voyage. A report, by cable, read:

The Queen of Australia from Quebec for Liverpool went ashore at Cacouna but afterwards came off without assistance, damage if any not yet ascertained.10

Cacouna is situated on the east bank of the Saint Lawrence river, about 100 miles seaward of Quebec. A later report gave more bad news:

The Queen of Australia from Quebec 2nd Inst. and following days had greater part of deck cargo washed overboard.11

Coming from Quebec, the deck cargo was very probably timber of some sort, and John Isbester as chief mate, possibly advised by Captain Jardalla or the longshoremen, would have been responsible for the lashings which should have secured it. Loss of deck cargo is not uncommon in the most severe weather, and could be due to ferocious conditions, to poor ship handling and/or to inadequate securing. In any event there were doubtless lessons to be learnt.

1 Cogle, Capt. Robert S, Letter to The Shetland Times Ltd, Lerwick, undated early 1914 (Isbester Collection).

2 Laing, Robert. Letter to Christina L Jamieson, 17.06.1884 (Isbester Collection).

3 Liverpool Watch Committee Order Book, entry dated 12 November.1878, Liverpool City Archive.

4 Liverpool Watch Committee Order Book, entry dated 17 Dec.1878, ibid.

5 The account which follows is based upon the Report of U.K. Formal Investigation No.1171 Cumeria.

6 This phrase from the Report of the Formal Investigation 1171 Cumeria is not understood.

7 Cumeria Agreement, Voy.14.01.1881–14.11.1881, Maritime History Archive, Newfoundland.

8 The only person signed on with a name like Johnson was E.G Johansson, AB. Cumeria Agreement, ibid.

9 Isbester, Jack, HCMM Cadet Log, cargo loaded on Clan Maclachlan in Calcutta for Liverpool in 1952 (Isbester Collection).

10 Lloyds List, 24.11.1883.

11 Lloyds List, 17.12.1883.