Читать книгу Hard down! Hard down! - Captain Jack Isbester - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2 GOING TO SEA – ARTHUR IRVINE

ОглавлениеStarting a career at sea in the 1860s was tough. There are no letters describing John Isbester’s early days at sea, but Arthur Irvine, son of Magnus Irvine of Strom Bridge, Whiteness, was aged 15 when he left home in April 1867 to start his life as a seaman. He was my grandmother’s elder brother – John Isbester’s brother-in-law to be. Magnus Irvine was a farmer and landowner – a laird – his wife’s family listing doctors, army officers and clergymen amongst their ancestors, so the choice of a life at sea, starting as a boy or ordinary seaman, is surprising. It may hint at a determination to see the world, a recognition that he was not academic, or that the family did not at that time have the funds to launch him in a professional career.

Travelling from Shetland to Glasgow, where he hoped to find a ship, was in itself a major challenge. David Hobart, the Whiteness schoolmaster, a Scot returning home, described the two-day voyage from Lerwick to Aberdeen via Kirkwall and Wick also in 1867, in the following lively terms.1

We started from Lerwick before one o’clock on Tuesday morning2 and steamed at an immense rate down past Dunrossness. When we came to the Sumburgh Roost [the area of overfalls and disturbed water south of Shetland] the sea began to be rather rough and the vessel rolled and pitched a good deal but not so much as makes me sick. After that I turned in and had a sleep and awoke about five o’clock in the morning. Going on deck I saw the Fair Isle far astern looking up out of the sea with a helmet with a deep cut across the top of it. The wind was still blowing hard and the sea raging and the weather very cold. So I turned in again and slept a good while and on again going on deck the Orkneys were well in sight. And the way through them very devious. It would indeed require a man who knew them well to guide a vessel through them in the night. We arrived at Kirkwall at about eleven o’clock A.M and started at 1.45 P.M. the wind blowing heavier than ever but being in the lee of the islands we had pretty smooth water. However when the Pentland Firth was opened the vessel rolldt and stachered like a drunken man. This did not last long as we soon got under the lee of Caithness and in due time arrived at Wick where we remained till I got wearied and went to bed. When I awoke next there was a change indeed but very much to the worse. Before this we might be said to have had a tolerably good passage but now the tossing was more than ever I saw it in the Queen [a previous ferry] and the smell around me was quite sickening. So it was not very long till I also gave up what I had put down and then I was all right and went to sleep about five o’clock in the morning and awoke to hear the wind blowing as hard as ever but the vessel having now gained the lee of the shore was in tolerably smooth water and so it continued till we reached eleven o’clock A.M. on Wednesday but did not get in on account of the tide till the P.M.

On a small ferryboat, probably the 15-knot paddle steamer St Magnus, all aboard were aware of what was going on. The bridge must have been just above the saloon. After a trip in 1869 David Hobart reported3

Friday night was very dark & we nearly ran down a vessel off the coast of Aberdeen. There was an awful roaring & shouting to back the engines & port the helm – helm hard to starboard & so on which were mingled with the shrieks of the ladies in the cabin who thought something terrible had happened or was going to happen. However, we steered clear of her in spite of rain, fog and darkness held on our way till we came to Aberdeen where we landed about two o’clock on Saturday morning.

Arthur Irvine may have been travelling with other Shetland men. In his letter4 to his mother from Glasgow he mentions A. Tait.

Dearest Mother,

I arrived here safely today. I went to Moore and he said that if I would wait a week he would get a ship for me. I am very tird and therefore cannot write much but I will write when I get a ship. If I do not get one tomorrow I will perhaps go to Liverpool with A Tait. If I do get a ship it will likely be for eight months and then I will be home. Give my Love all I have not written to Granny but you can tell her that I am finely write immaditely to the Sailors’ Home Glasgow.

I remain your loving Boy

A Irvine

Don’t put C in the adres

Like many a 15-year-old boy he was concerned about appearances, and didn’t want anyone to know that his middle name was Craigie!

A fortnight later he was still awaiting a ship in Glasgow, and resisting the many temptations of a sailor’s life.5

My dearest Aunt [probably Elizabeth Gifford of Busta, his mother’s 38-year-old sister],

I am sorry that I have not written to you before but I put it off till I should get a ship. I find now that it is all very fine to be at home and speak about the sailor’s life but it is different to try it. Dear Aunt I find now that it is all true that I was told about the sailors although I have not yet been at sea The wickedness of a sailor’s life on shore here is awful Last night a steward on board a steamer came here paid off with £30. He went out and came in with only £2 & without his coat & that is the way why a sailor can’t have money but by God’s strength I sall never do that I have had Many temptations since I came out here, but I have resisted them from the first and now I find that it is easier I have been twice every Sunday at the sailor’s chapel since I came.

Kind love to Granny, Uncle, Mrs M and the children and tell them that if I am spared to come home I shall bring them something nice Write next post both you and granny

I remain your loving nephew

Arthur C Irvine

My adress is Mr Burgess Seamens Bordings 34 Brown Street Glasgow

By July 1867 Arthur was well into a voyage aboard the barque Emerald and, writing6 to his sister Mary Jane, a year older than him, was voicing his distress at the failure of his family to write to him and at the heavy demands of the work required of him while in the port of Genoa. The absence of letters from family and friends has for centuries been a problem for seafarers, and on several occasions John Isbester was distressed when letters expected after a long voyage failed to reach him. In Arthur’s case the problem was probably caused by his failure through inexperience to provide full addresses or to take account of the time required for mail to travel home and then out to the next destination. But there can be no doubt that he was frequently in the thoughts of his mother, sister, aunt and grandma! If there were any prospects of work to be found ashore he wanted to be informed. He had also decided that his name was Al or Alle.

My Dearest Sister,

What is the reason I have got no letter? I have written twice and received no answer. Is our people angry with me or what? I am sick tired of this place and ship and seeing the Shetland lads geting letters from home and me geting none.

Private Make dear sister would you write to Constantinople and tell me if I should come home in winter or what are people is thinking about me? I know that there is something up, else I would have had a letter. If any of them is dead it is gust [just] as good for me to know it now as after but if I don’t get a letter in Constantinople this is the last they shall ever have from me so I must close for want of time tell D to write Love to all I remain your loving brother

Al

Adress to all on board the Barque emerald to the care of Hild & Mathers, ship brokers Constantinople

Private Dearest Sister

I have forgot to tell you something If you see any opening on shore about the time that I come to England for this is hurting me I can agrie fine with the sea work, but this harbour work would kill a horse Write me about 3 weeks and tell me.

Alle

It reads as though he and his fellow sailors were being used to do heavy work, discharging or loading the cargo. One letter which he never received, because it was never sent, was from his mother and sister. It provides a reminder that the laird and his family lived on a working croft, planting potatoes and oats, and were aware of much of the local gossip. In 1867, when Arthur was on his first voyage, his mother writes:7

Strom Bridge Whiteness Shetland 3rd May

My own darling boy,

We were all glad of your letters last week. I hope by this time you are getting on with your voyage & I hope you have fine weather. We have fine dry days now with north wind. We finished our oats on Friday and set some potatoes on Saturday. Andrew Garrick is finished. Annie sends her love to you. That is the only one of them we have seen. Kate writes that she wishes you had come to see her

After giving news of nine family friends and neighbours, she continues:

Now I think I have told you all the news Mary Jane will finish this to you with much love to your dear self I do hope you are taking care of yourself and not fighting with anyone dear darling boy do write soon. your own Mother WM Irvine Stromebridge

Mary Jane was ready to tell him of the scandals rocking the rural community:

My dear brother, How are you getting on? We are jugging along the best way we can. Laurie Morrison was bailed out but was no sooner out than Charles Duncan put him in again for £70 which he was owing him as his lawyer when they went to law about Jane Gibbs Rhilo, so he has to sit till he pays it. Peter Jamison Stromness hens are all dead & he has gone to law, for he say Nellies folk have poisoned them. The Police have been out & taken some of the hens in to inspect I doubt it will go hard with them, they are telling so many lies with love your Mary

Arthur was feeling better about life a few weeks later when he wrote8 from Constantinople to David Hobart, his former schoolmaster and lodger in his parents’ home; or perhaps, writing to a man and not a woman, he was looking for admiration rather than sympathy.

My Dear David,

We are Bound to Odessa to load grain and then I will have more time and write you a long letter Just now I am swearing for the Mate because he wants me to throw a line to the tug & I won’t. I shall try and bring home a turk home with me in winter give my love to all I am as fat as a pig and as strong as a lion you can writ to the General Post Office her and I will get it as I come down again [i.e returning south through the Bosphorus] we are Lying under the sultan’s Palace and the Mahomedans is saying their prayers so good bye for the present I remain yours truly

Ale

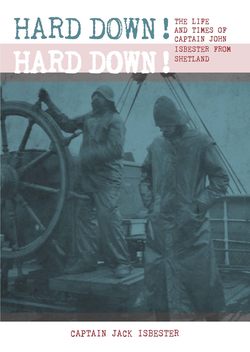

In a photo (Fig.2.1) taken about that time, Arthur does indeed look substantially built; but refusing the mate’s order after only four months’ sea service seems rather reckless. Perhaps he is really admitting that he couldn’t, rather than wouldn’t, throw the line to the tug – it’s a skilled task. What sort of turk he proposed to bring home remains a mystery to me.

Arthur did not return home in the winter of 1867–68 and the next surviving letter9 was written to his father a year later, in August 1868, from Runcorn.

Figure 2.1 Arthur Irvine

Dearest Father,

This is to tell you that I have left the New House & shipped on board this one which is called the Norwich Trader of Sunderland We are going to Peterhead with salt and expect to go from there with salt the Syran left here with salt for Lerwick yesterday I thought it very homely to hear my own native Language among the cockneys Dutch Welch and Scotch as soon as I hear it I was not long of singing out Do you belong to Shetland If I had got 20 or 30 £ I would have come with her You can tell David if he does not rube his Face well with crotin oil I shall have more whiskers than him as I can get hold of it with my Teeth

But I will send my things and then you can judge for yourselves as soon as I get to Peterhead. Give my love to all and write by return of post to peterhead so no more at present I remain your loving son

Arthur C Irvine

Adress Arthur C Irvine Care of Capt Sutherland Schooner Norwich Trader Peterhead Scotland

After 15 months at sea Arthur had grown a bit of a beard, had not saved much money, was aroused by Shetland accents and was thinking of returning home. However he did not do so, and his next surviving letter10 was, from the context, written in Greenock in April 1869, before he joined the Ratcliff.

Dearest Mother and Father,

I have shipped for Quebec and am as happy as lary The wages is £4. No advance but we have all taken £3.15 and £2 advance. She carries all Shetlanders tell Mary that Peter11 is with me so that he will be comming home neset winter. I won’t promise to come home neset [next] winter but I will see I am in a hurry as we sail tomorrow and I have got to go up to Glasgow for my things Kind love to all. Write in about a week to Quebec. Your loving boy

Ale Irvine

That was the last his family ever heard from him. In Quebec he died by drowning on Saturday 5 June 1869, aged 17, although the record12 of his burial in the Hôpital de la Marine on 14 June describes him as aged 22. (In those days seamen in their sixties understated their ages while youngsters evidently did the opposite.) Arthur Irvine was shown in the Ship’s Articles as aged 20. The ship’s official log book records, in an entry signed by the master, the mate and one of the Shetland ABs:13

June 5th 1869 8PM Arthur Irvine while in the act of taking a rope into the boat fell into the river and sunk [sic]. The alarm was immediately given when all hands got onto the booms to use every effort to save him but the man never again rose to the surface. The body was dragged for but [they] did not succeed in finding him.

From his subsequent burial it is clear that his body was later found. Family tradition is that he fell from the ship’s gangway. It is likely that Ratcliff was at an anchorage and access to the shore was by boat. Saturday evening, after drink has been taken, is a dangerous time, and the access to the ship is often a dangerous place. Whatever the circumstances this was a tragic loss of someone at the very start of adult life and serves well to illustrate the precariousness of life at sea in the 19th century.

Arthur Irvine’s effects, after more than two years at sea, are listed in the Official Log Book14 as:

Three pair of trousers, two guernsey frocks, two red singlets, two coulered flannel shirts, 3 jumper frocks, 2 pair of drawers, 2 sleeves, 1 waistcoat, 1 black waistcoat, 1 coat, 1 blanket, 1 rug, 5 pairs of socks, 1 towel, 2 caps, 2 comforters, 3 mits, 1 pair of braces, 1 bible, 1 pann, 1 knife, 3 sticks of tobbaco, 2 handkerchiefs, all stored in his chest.

Arthur’s wages for six weeks work as an AB were £5 7s 6d, from which were deducted a £2 advance and 5/- for the tobacco, leaving wages of £3 7s 6d due to him. It is likely that his family only learnt of his death from fellow Shetland crew members as the Ship’s Articles showed simply that he came from Shetland.

David Hobart, on holiday in Scotland in the autumn of 1869, had apparently been making enquiries on behalf of the family about any outstanding wages due to Arthur Irvine. He wrote:15

James Spence gave the number of the vessel required; it is 15686 and the port she belongs to is London. The only thing wanted now is the amount of wages he received when she sailed. But that might be found out by writing to the owners Hall Brothers, Great Chare, Newcastle-on-Tyne. I shall write and ask them to send you word, or if you thought it would be too long to wait you might send in the official number & the port she belongs to at once to Mr Nicolson & he would fill up the shedule & give it to me.

Happily John Isbester, the primary subject of this book, survived and was strengthened by his early years at sea. It was not until 45 years had passed that my grandmother, a little girl when her brother died, was to be exposed to another heart-breaking maritime disaster.

1 Hobart, David, letter H3 of 03.10.1867 (Isbester Collection).

2 From the context it is clear that this was 1.00 pm.

3 Hobart, David, letter H16 of 27.09.1869 (Isbester Collection).

4 Irvine, Arthur, letter A1 of 05.04.1867 (Isbester Collection).

5 Irvine, Arthur, letter A2 of 21.04.1867 (Isbester Collection).

6 Irvine, Arthur, letter A3 of 16.07.1867 (Isbester Collection).

7 Irvine, WM & MJ, letter WMI1 of 03.05 1867 (Isbester Collection).

8 Irvine, Arthur, letter A4 of 23.08.1867 (Isbester Collection).

9 Irvine, Arthur, letter A5 of 02.08.1868 (Isbester Collection).

10 Irvine, Arthur, letter A6 of 21.04.1869 (Isbester Collection).

11 Ratcliff Articles of Agreement, 1869, The Maritime History Archive, Newfoundland, list Peter Goudie and Peter Anderson, both from Shetland.

12 Quebec, Vital and Church Records (Drouin Collection), 1621–1967 Record for Arthur Irvine.

13 Ratcliff Official Log Book, 1869. The Maritime History Archive, Newfoundland.

14 Ratcliff Official Log Book, 1869, ibid.

15 Hobart, David, letter H16 of 27.09.1869 (Isbester Collection).