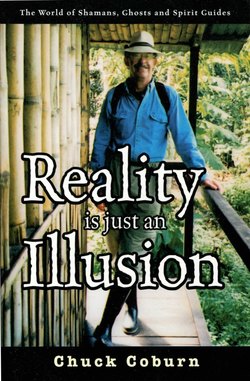

Читать книгу Reality Is Just an Illusion - Chuck Sr. Coburn - Страница 18

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

A Social Call

ОглавлениеFollowing our morning reflection with the shaman, John offered to take whoever wished to join him on a physical journey into the depths of the jungle to "do lunch" with a compadre of Juan Gabriel Carrasco, John's affable Ecuadorian partner and our guide. Whether we were to share a meal with or were to be the meal for this headhunting culture wasn't made entirely clear—but after having survived the previous evening's adventure and with the instructions of the shaman still ringing in my consciousness, I was game for just about anything.

We followed a narrow footpath made muddy by recent rain, slogging along in the knee-high wading boots we had purchased from the back of an old truck at the airport. Although it was not an easy hike, we were seemingly never out of breath, likely due to the quantity of the oxygen produced by the abundance of thick trees and plants all around us.

In addition to not being overly tired, I noticed how much more at ease I was in the thick forest, even though I was being led away from the security of our encampment hundreds of miles from anywhere, faithfully following a native guide I had met only days before. Somehow the entire environment was less fearful than it had been before consuming the ayahuasca. For some reason I had acquired a new sense of acceptance and belonging. It was as if the rain forest was observing and protecting me at the same time.

"Funny you should say that," I heard a female voice say from somewhere close behind me. I was immediately brought back to the present moment.

"That's the name of my first book," I responded, somewhat flippantly, perhaps exercising my newly found self-assurance and power.

"No—I mean funny you should have seen the eye-shaped beacon.”

I turned to realize that Lynne, my sober companion from the ayahuasca journey, was speaking to me in absolute seriousness about something I had said the previous night while under the influence of the hallucinatory drug.

"I work for a rather . . . shall we say . . . secure section of the government and there is a fair amount of literature detailing alien eyeshaped beacons buried all over the planet,” she continued. "I was interested in your description because—" She stopped abruptly, mid-sentence.

"—forget it," she finished, apparently realizing that she had said more than she should. She quickly moved several people ahead of me in the line of gringos forging the jungle path. Further attempts throughout the remainder of our trip to get her to elaborate on this subject revealed little more than a nervous smile.

As we continued walking in silence along the well-traveled but narrow, rain-soaked footpath, Juan Gabriel suddenly stopped and let out a loud hoot.

"It's the custom,” he responded to our questioning looks. "It's like the jungle doorbell."

I figured we must be close to our destination, although I couldn't see any signs of a hut or village. I couldn't believe how comfortable I had become in what was previously a frightening environment. What I formerly viewed as an austere jungle had become an inviting forest—the heavy pure oxygen became an elixir and the snakes elected to be elsewhere.

I had long given up attempting to discern how Juan Gabriel knew exactly where we were, since one tree looked quite a bit like another. But I supposed he would think the same of our hectic freeways and confusing city streets.

Referring to "the jungle doorbell,” he explained that men are gone for long periods of time, hunting or raiding another village. It is an accepted fact that their wives might "entertain" other men during this time, and a returning husband does not want to have to confront a tribal member in a compromising situation.

The reason this custom exists is because the life span of men in this environment is relatively short. The head-hunting wars, we were unofficially told, still take place. Therefore, anyone approaching a hut without first announcing their presence is presumed to be an antagonist and either the "approacher" or the "approachee" might end up dead.

"You know,” Juan Gabriel added with a laugh, "the guy with your wife might be a good friend, so you would rather not have to deal with what you can avoid."

The group let out a collective sigh when the sound was returned, indicating that it was safe to proceed. We climbed a short hill and came upon a large oval-shaped hut that probably measured about seventy by twenty feet. It was constructed from long straight tree timbers connected by smaller sticks and covered with large leaves. From the inside, one could see the truss-shaped roof design. My construction background made me question the integrity of the arrangement—it would have not passed muster by U.S. building inspectors. However, many generations of use testified to its worthiness in this environment.

We followed Juan Gabriel and John inside, where we promptly formed a single line to individually meet our host. The Shuar warrior whose house we were in was seated with his back to the only interior wall. This wall separated the larger receiving room from the family's private quarters. His wife and children remained sequestered behind the partition as we each approached to shake his hand. He was dressed in a single cloth wrapped around his waist and he sat on a log, sharpening the tips of handmade blowgun darts.

We had been coached during our hike to this destination by Juan Gabriel about proper protocol in a native home. He cautioned us that, because this culture was quite different from our own, it was very important not to make a faux pas. Juan Gabriel had repeated the three most important points over and over again during the three-hour journey:

1.Avoid eye contact with tribal members of the opposite sex, because to do otherwise is to outwardly flirt . . . and we all had a fresh recollection of Juan Gabriel's story about how these people settled their disputes.

2.Remain seated. Do not venture behind the head of the household, and certainly not behind the screen where his family is sequestered. To do so would be a major insult—we shuddered to think of what might happen if we did.

3.Do not, under any circumstances, refuse to drink from the communal chincha bowl when it was presented by the warrior's wife.

The third directive, as it turned out, was the toughest assignment.

Chincha, as you know by now, is made from a bitter-tasting manioc root that, after being chewed for an extended period of time, is then spit back into a pungent-smelling, lumpy, milky-appearing substance and allowed to ferment. John assured us that it was not at all like ayahuasca and was considered a social drink.

"Chincha,” he said, "is alcoholic—a sort of beer, but not a hallucinogenic." When asked about the potency, he replied, "Depends on how long it ferments—anywhere from about three to twelve percent. Whatever the proof, it'll knock your socks off!"

Having been cautioned numerous times that it would be a major insult to the host if we declined the oatmeal-thick bitter drink, we watched both Juan and John down the contents, smile, and hand the bowl back to the warrior's wife. Then it was our turn.

It was worse than you can imagine. We were offered the drink over . . . and over . . . and over. After about the fourth helping, I think it got to Shirl and she began to get somewhat giddy. She started to laugh . . . quietly at first, then her body began to shake uncontrollably as the fermented brew affected her. The woman seated next to me pointed out that the our tribal host had begun to sharpen the blowgun darts with a little more vigor as he glanced more than once in Shirl's direction. But then, fortunately for us, lunch was served. It wasn't bad once you got past the fish eyes and plantain.

Later, after getting to know the family (and receiving personal blowgun lessons) we began to appreciate the honesty, the beauty, the simplicity that is their lifestyle and environment. The word stress is not in their vocabulary. We began to comprehend firsthand the oneness of the people and their surroundings.

No clocks or schedules to make pressured demands on their lives, no unfulfilled egos to drive them to some unobtainable goal, no fear that death is the end of all existence to haunt them. They live the concept that we are truly one with all things. They illustrate an important lesson: we can gain a greater understanding of our true nature and the reality of all things by simplifying life, respecting the planet, and living in the present.