Читать книгу Ellsworth on Woodturning - David Ellsworth - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction – The Creative Process

ОглавлениеMy father, Ralph Ellsworth, was an academic librarian, so it was drilled into me from an early age that the reader has a right to expect a certain amount of wisdom from every book he reads. Now, this might seem ambitious for a book about woodturning, but I’ll work on that. My real problem is whether there’s an age requirement for wisdom. That said, I have taken the somewhat conventional stance that the creative process, like cell division, is ongoing. If I miss something the first time around, there is always the possibility of a second edition. And were that to happen, I promise to mount my soapbox and wave the flag of wisdom from the very first page.

This book is about developing bowls and hollow forms made from wood and turned on a lathe. This is what I do. And I specifically use the word “develop” because, while I have been a maker of objects since childhood, I was slightly past thirty when I began to establish the focus of my creative energies. Thus, while I intend to provide a complete account of my knowledge on this subject, I also expect those of you who follow my lead to fumble, mumble, and outright fail in many of your attempts at making these objects, especially hollow forms. Failing is good: It’s just part of the process. And if you don’t blow up a few pieces along the way, you’re either taking the safe way out or being entirely too serious about the whole woodturning experience.

The great value of turning objects on the lathe is not so much what you make, but the process you experience when making it. It is the power of this process—the direct engagement with a material, of making something that is within the mind’s eye, and of being totally accountable for successes and screwups—that allows you to evolve from object to object throughout the rest of your life.

What, then, does it feel like to experience a relationship with a material through a process? Can you learn to laugh, to enjoy that inner pride when something actually does come off the way you planned it, or even when you didn’t plan it? Or maybe it’s simply that you have created a block of time to be by yourself...just for the opportunity to experience the experience of making.

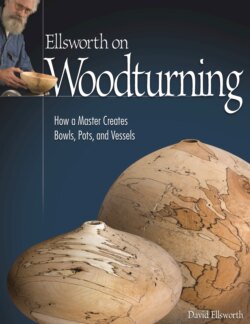

David Ellsworth, Spirit Form, 2000. Lacewood; 2" high x 6" wide x 6" deep. These low forms are some of my favorites. They evolved from hard-edge low forms I made during the mid 1970s.

David Ellsworth, Walnut Pot, 2006. Claro walnut burl; 6" high x 8" wide x 8" deep. I frequently create this type of full-volume form to let the beauty of the wood speak for itself.

To help explain what I feel when turning on the lathe, let me tell about a little boy who grew up in two worlds. The first world, his winter world, began in the middle of America—1944, in Iowa, with snowy, gray winters cold enough to chill the bones through all of the layers of a woolen snowsuit. Growing up in Iowa in the 1940s and 1950s gave a kid a solid foundation for just about everything. You learned to live by the Golden Rule, you went to church, you got a good education, you knew your friendships would last forever, and your horizons were always in view. Iowa was a good place to grow up, and once you’d moved away, you knew it was a great place to be from.

The boy’s second world, his summer world, came with his family’s annual trips to their cabin in the mountains of Colorado. This was where things really happened, where his fantasies became reality, and where there was no horizon beyond which imagination could not see. In this world, you didn’t just play cowboys and Indians; you became cowboys and Indians. His role was to make their toys of battle: bows, arrows, and quivers; tomahawks and slings; knives, spears, whips, and guns. All were created from wood and leather, using the simplest of tools: a handsaw, a knife, a hatchet, and a punch that had been a nail. Here, the boy would explore the forest and the rivers, and challenge the Chinook winds by leaning into them over rocky cliffs. The sounds and the smells, the texture of the land and the light of the darkening sky, became his teachers, and this is where he learned the value of being alone while never feeling lonely.

In the summer world, the boy heard many stories of the Native Americans from an elderly Blackfoot man named Charles Eagle Plume. The story that he enjoyed the most told how a warrior could walk silently through the forest... even at night. And so, he taught himself to move without sound by placing each downward step toe-first, to discover the rising of the earth and how to meet it with equal force. He then learned to reach with outstretched arms to the trees and the rocks, first in the daylight with eyes closed, and then in the dark, discovering their energy, the radiance of their warmth, and their smell. In his many trials, he would mostly fail. And when he finally did succeed, it was only after accepting the presence of his surroundings as an equal to his own.

That boy was my past, and though over the years most of those toys have disappeared, the memories of my childhood interactions with the natural world and of me as a maker remained. And yet, it would take many years, long after I had developed my skills as a craftsman, before I realized how these childhood interactions related directly to my experiences in turning wood.

Specifically, I learned to let the tip of the sharpened tool seek the energy of the wood not as a conqueror, but as an equal. And I realized that a successful cut occurred only when I presented the tool to the wood as if the two were shaking hands. I learned to sense the varying densities of my materials, and to adjust the energy of the cuts so that I could work as efficiently at 30" off the tool rest as at 3". Sound helped determine wall thickness, not simply because a thin wall makes a tone when being cut with a tool, but because the consistency of the wall thickness relates directly to the tones produced.

And then there are the smells: the ponderosa and piñon that always seemed to be a part of my surroundings, the fresh-cut sugar maple from the first cabinet shop I visited when I was twelve, the sugar-sweet odor of Brazilian rosewood, and the acrid smell of zebrawood that made me cough and think of camel dung (whatever that smells like).

Teaching oneself a skill without a teacher available is laborious, yet ultimately self-fulfilling. I learned each mistake one day became a learning tool for the next, and swearing was a good thing if it helped me understand that catching the tool in the wood wasn’t the tool’s fault after all...or the wood’s. I learned to make my own tools, to develop my own techniques, and to challenge the limits of my own experiences. Equally important, I learned to become a problem solver. Years later, I would realize all highly skilled craftspeople are also highly skilled problem solvers.

In looking back to my first experiences at turning hollow forms during the mid-1970s, I have come to realize something carries us daily from where we have been to where we wish to be, and it goes beyond the beauty of wood, the ingenuity of our tools, or the power, fragility, subtlety, or grandiosity of our objects. It relates to our engagement in the centering process. I have heard many other creative people refer to this same experience, whether it involves drawing, throwing a ceramic pot, blowing glass, or beading. I simply refer to it as the process of discovering that wonderful element of personal mystery. So, throughout this book, I will do my best to pass on all of my knowledge and skills, but I will not take away your right to discover for yourself the personal sense of mystery that evolves for you through the turning process. This mystery will be your gift to yourself...and so it should be.

David & Wendy Ellsworth, Collaborative Mandala Platter, 1990. Satinwood and glass seed beads; 1" high x 13" wide x 13" deep.

David Ellsworth, Natural-edge bowl, 2008. Poplar; 7" high x 8" wide x 7" deep.