Читать книгу Ellsworth on Woodturning - David Ellsworth - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

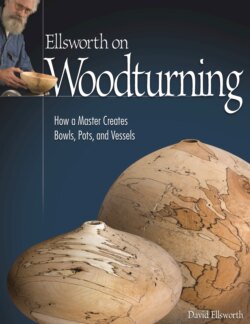

Spalting wood

ОглавлениеSpalting is Mother Nature’s way of turning trees and other organic materials into the forest floor. Spalting is a natural process in which fungi attack the living cells of organic material. This process occurs in dead or dying trees, leaves, or any other compostable material. I have been told the fungi exist throughout the earth’s surface, but they only manifest in areas where there is both heat and moisture. I guess that eliminates the Arctic and most high-altitude or desert regions.

The spalting activity decomposes the cells in wood, with the result that it also reduces the natural tensions or growth stresses within the material. The reason it's important to me is I know I will get somewhat less overall form distortion when turning a spalted piece of wood compared with a non-spalted piece. In fact, some spalted pieces are so decomposed there is no tension left in the wood and, therefore, no distortion in the finished piece, even though the wood was dripping wet when I turned it.

The reason most turners use spalted wood is that the material can be intoxicatingly beautiful. The dark graphic markings left by the spalting activity—technically known as melanized pseudosclerotial plates, but commonly called zone lines—record the progress of the spalting activity as it migrates through the wood along the long fibers. The zone lines come in various colors from brown to black, depending on species. They are also wickedly destructive to any sharpened tool edge—like those of chain saws and band saws, for example—as they are no longer part of the wood, but made of a carbonized, iron-based composition.

Dark zone lines, which are created by spalting activity, are destructive to sharp tool edges but can be very beautiful when incorporated into a piece.

Creating effects in the log

I’ve discovered a variety of ways to help Mother Nature create interesting effects in logs of my choosing. For example, some years ago, I inadvertently left a section of an ash log sitting with the end grain directly on the ground. I forgot about it until, one day a year later, I turned it over and trimmed off the mud to discover that capillary action had drawn the minerals out of the soil and turned the log from the original ash white to a rich gray–honey brown. I’ve had mixed results when trying the method with other woods like maple and oak; in most cases, I would simply get spalting activity, sometimes mixed with a little rot. The lesson is this: Don’t be afraid to experiment if there’s a certain effect you’re seeking. Who knows what Mother Nature will cook up?

Whether working with these active spores is safe is an unanswerable question. I’ve posed it to my students who are doctors and I get a very consistent answer that sounds something like this:

“The active spores in spalted wood don’t actually cause a definitive lung disease, but like all wood dust, they certainly will fill the sacs in lungs, which can lead to lung disease.” And then, “For some people, there may also be an allergenic problem with mold.” My solution is to be cautious and wear dust protection when working with spalted wood and especially when sweeping out the workspace.

Other times, when I take down a tree, I’ll cut the log into rounds with lengths corresponding to the height or the diameter of what I’d like to make. I then leave the log on the ground with just the space of the saw cut between the rounds. Depending on rainfall, sunlight through the trees, and maybe some beer, and a little yeast, I’ll get spalting entering from both ends of each round.

On the other hand, if I want spalting only on one side of the finished piece, I’ll cover one end of the round with plastic and leave the other end exposed to the elements. The effects can be interesting—sometimes quite dramatic, sometimes junk. It’s worth using your imagination and experimenting to see what comes about.

On occasion, I will turn a vessel form to a finished shape, then wrap it in plastic with a few shavings from a heavily spalted piece of wood. After a few months, the vessel's surface will begin to spalt, and I can trim the shape and hollow it out. The result is a spalted surface exactly where I want it. To stop the spalting process and kill the fungi, simply dry out the wood.

In the late 1980s, I wanted to introduce some gray tones to the sapwood of a piece of redwood lace burl I was working on. To get the gray tones, I tried to spalt the sapwood area by wrapping it with some spalted maple shavings that contained a good dose of powder post beetles. I hoped this would advance the spalting process through the holes the beetles would drill into the wood. It worked, but it took a year and a half because I’d forgotten how resistant redwood is to bug and bacterial decay. That was the longest amount of time I ever spent making a piece! (See photo on page.)

Experience becomes a huge factor when working with green wood, but I think the most important lesson is to understand the wood is going to change. By learning about changes and remaining open to them, many new design opportunities have opened up to me. I also have learned about changes in myself that have allowed my design aesthetic to grow, the most important being to keep an open mind and not to get stuck with any rules about what I think I’m supposed to do, but rather remain open to what is possible.

Spalting your own wood

Sometimes, Mother Nature doesn’t spalt in the area of the logs where you want spalting. That doesn’t mean you can’t help her out. To help your logs spalt, try leaving them outside and open to the elements if you live in a humid area. I like to leave a small space between the logs. Add beer or yeast if you wish to speed the process along. If you live in an arid climate, try bagging the logs with shavings from spalted logs.

Leave the logs on the forest floor to spalt. Allow a small space between the logs, and feel free to sprinkle yeast or pour beer over the logs to accelerate the process. Shavings from a spalted log will help, too.

After a few months, remove the ends of the logs to check on the condition of the spalting.

As you can see, the experiment has been a success; spalting has spread throughout the logs.