Читать книгу Ellsworth on Woodturning - David Ellsworth - Страница 21

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

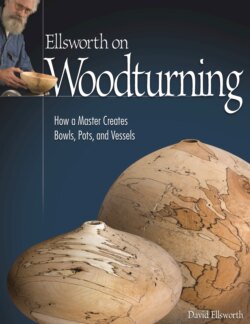

Why Turning Tools Work

ОглавлениеEvery time I pick up a woodturning catalog, the number of new tools available just knocks me out. Compared with the simple scrapers and gouges available when I started turning, today’s lot is a vast improvement. It is also vastly complicated—especially for beginning turners—trying to figure out which tool will work best for a given task. Will it work on green wood as well as dry? With balsa as well as rosewood?

Over time, most turners develop a working familiarity with their tools, or at least a certain confidence in knowing what a tool is supposed to do and how to make it work. But when it comes to understanding why a tool works (or doesn’t work), that’s when many people begin to scratch their heads. It just seems a lot easier to say, “This is my favorite tool,” instead of “This is why my tool works.” So, it’s that “why” part that I’d like to address.

Bent tools are used for hollowing. They can be made in many sizes and angles to reach any part of the interior of a hollow form.

Observe the cross sections of the razor (skew), ax (gouge), and splitting maul (scraper). Skews are sharpest, but lose their edge the fastest. Scrapers hold their edge longest, but cannot get very sharp due to the angle of the edge. The compromise is the gouge, which is not as sharp as the skew, but holds its edge longer.

Turner’s phrases defined: If you don’t “ride the bevel,” the tool can “back up on you”

The bevel is the curved area on the end of a gouge that intersects with the flute to form the edge. It’s the bevel you sharpen when you go to the grinder. When making cuts on the wood with a gouge, you rest, or rub, the bevel against the wood and advance the edge forward to begin the cuts. This is also called “riding the bevel.” In effect, the bevel stabilizes the edge as it flows through the wood in the same way a fence stabilizes the wood when working on a table saw or jointer. Without support of the bevel (or the fence), the wood would become unstable and the cut inaccurate, if not outright dangerous.

You also ride the bevel when working with a skew chisel on a spindle. And as most turners have experienced, if you inadvertently raise the bevel off the wood during a cut so that only the edge is in contact, the edge will catch and the skew will travel backward instead of in the forward direction you’d intended. While this is not usually dangerous to the turner, it does leave a rather deep, flowing spiral groove on the wood, the beauty of which is generally matched only by the intensity of the language that follows. This action can be referred to as the tool “backing up on you” or “catching the tool on the wood.”