Читать книгу Ellsworth on Woodturning - David Ellsworth - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

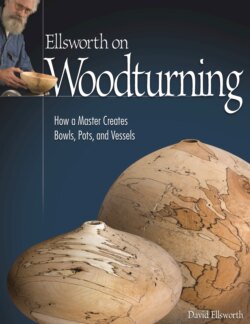

ОглавлениеChapter 1

Working with Green Wood & Dry Wood

The universal law in all of woodworking is that wood moves. Dry wood, having released most of its moisture and done most of its moving, is more predictable and stable than green wood, the fibers of which are full of moisture yet to evaporate. Naturally, the processes for working with dry wood and green wood differ, though working with a wood that is either air- or kiln-dried is no guarantee movement will not occur. Whether working with dry or green wood, you can use “wood moves” as a credo; it will help to explain your various aesthetic approaches, design styles, and methods of work.

David Ellsworth, Hickory Pot, 2006. Hickory; 7" high x 8" wide x 7" deep. The pith runs diagonally through this form, creating distortion through the piece.

David Ellsworth, Bowl, 2004. Poplar; 4" high x 9" wide x 7" deep. This rough-turned bowl shows rise in pith areas where the shrinking long grain fibers have pushed the end-grain fibers out and up.

You must consider a variety of factors when evaluating a species for your piece. This choice is affected by color, texture, personal preference, and the function of the piece. However, consideration must also be given to the wood’s inherent potential to move, as that will ultimately affect things like type of finish and choice of joinery—in fact, even whether joinery can be used at all. Additionally, magnitude and direction of movement often will be inconsistent throughout certain species. This is why you would not generally use madrone burl, eucalyptus, or lignum vitae to make dovetail joints...at least not more than once. Successful joinery depends on appropriately oriented grain, the right glue, and a functional finish. The most beautiful design might fail if the wood movement is not considered. Movement in wood is a critical influence in how you approach design and even what type of objects you design. All of these methods of work not only reflect the processes you use when making, but also accommodate movement of the materials.

Working green wood versus dry wood

It is tempting to draw a line between woodworkers according to whether they use green or dry materials. When working with dry wood, the end result is very predictable and directly reflects the original design. Drawings are almost always required, and, assuming you remember to measure twice and cut once, the finished object will most likely look just like the drawing. In this respect, working with dry materials is in most cases like color photography: What you see is what you get.

By contrast, working with green wood is like diddling with the developing process in the darkroom, trying to get that ultimate black-and-white print. When turning green wood, you can tinker and toy, but you can’t guarantee a board will stay flat from dawn to dusk, much less from season to season. You can’t make a dovetail joint. You can’t sand without gumming up your sandpaper. Finishes don’t dry, because the wood isn’t dry. Sketches are a great place to start, but detailed drawings are useless. Worse, customers don’t much care for that telltale pop when their beautiful new bureau top splits open in the middle of the night.

Why work with green wood?

So what’s the big attraction in working with something you can’t control?

Well, when I started working with green wood in the late 1970s, I quickly realized control was the wrong approach. As soon as I replaced that term with discover, I encountered an entirely new path in working with wood. The great challenge in working with green materials is anticipating what direction the movement might take and how much might occur.

In this respect, the turner of green materials works very much like the potter, the glassblower, and the jeweler, in that he must learn the intrinsic nature of his materials—and their movements—in order to become an effective designer and maker.

The distortions in the green-turned bowls shown here are predictable, and therefore, you can easily project these movements into your design. The rim movement in the poplar bowl at left is subtle, whereas that in JoHannes Michelsen’s cowboy hat in madrone burl (below) is dramatic. The hickory pot, shown on page, presents the eye with a very unusual shape: the wood movement was utilized simply by orienting the grain diagonally through the form. This sense of movement takes the form out of the realm of bowls and brings it up to the level of a sculpture.

One hazard of turning green wood is a bowl isn’t necessarily a good bowl just because its shape is distorted. I have produced a lot of dogs over the years while learning how to manage green materials so that my successes would outweigh my attempts. Each new log or root or burl becomes a challenge, and I am always seeking a balance between what I think I know and what I have yet to learn. One of my early learning experiences was the apple hollow form shown on page. At 9" in diameter and 1/16" thick, it was a real challenge just to make. After it dried, I realized how much the distortions in the surface competed with the shape. The hard-edged rim and the undulating top just made the form look strange.

JoHannes Michelsen, Cowboy Hat, 2001. Madrone burl; ¾" high x 2" long x 1½" wide. The surface distortions in this hat reflect the internal tensions within the burl during the drying process.

In truth, we “greenies” seek movement in our work, while the “plankers” seek to avoid it. Now don’t take offense at these terms, because ever since I started working with green wood, I’ve been ribbing my furniture friends about their use of dry wood. They, of course, come right back with the notion that my green chest of drawers might be a little difficult to sell. And I respond with, “Yeah, but my old man made a love seat out of green aspen wood back in the ‘40s, and I am living proof that it worked just fine.” And on it goes.

David Ellsworth, Vessel, 1978. Apple; 4" high x 9" diameter x 1/16" thick. Distortion competes with the hard-edged design of this hollow form, demonstrating that not all green wood forms end up as winners.

David Ellsworth, Vessel, 1978. Walnut; 7" high x 8" wide x 8" deep. In this piece, I made the classic mistake of trying to make the biggest hollow form I could out of a block and ended up positioning the pith right next to the entrance hole. It gave the hole an interesting lilt, but I saw these elements as competing within the form. Early experiments are sometimes the best teachers.

An extraordinary wealth of raw material

There is much to say in defense of greenies. We get to work with an extraordinary wealth of raw material that is available to us, most of which is free or very inexpensive. We get to pretend we’re real woodsmen and tromp around in the forest listening to the birds and experiencing all the other wonders Mother Nature has to offer. We get to learn what a tree actually looks like, including its shape, color, bark, and leaves. We get to pull the poison ivy vines off downed trees and choose whatever tree part we want to work with, including the trunk, limbs, crotches, stumps, and even the occasional burl. We get a chance to meet the owner of the property where the tree came from, and maybe make a nice trade for a few finished salad bowls. And if we’re really, really lucky, we’ll also do a bit of trading with our chiropractor at the end of the day.

The main problem in working with green wood, besides the fact it’s tough to make a chest of drawers with it, is you can’t go to school to learn about it. Instead, you simply have to get out there, get dirty, and do it. Once you’ve seen that raw color and smelled that fresh odor and watched the patterns of grain in the various regions of the tree—you’ll never again look at a bowl or a vessel or a finished piece of furniture without a quiet appreciation. The more you know about your raw materials, the broader your experiences will be, and the more fluid your life as a designer and maker will become.

David Ellsworth, Black Pot-Dawn (detail), 2000. 7" high x 3½" wide x 3½" deep. This piece of ash shows the effects of fire. The soft-spring grain fibers show deep etching in the surface from the flames. The result is a striated pattern showing the movement of the grain through the form. For more about using fire, see Chapter 16, “Finishing,” on page.