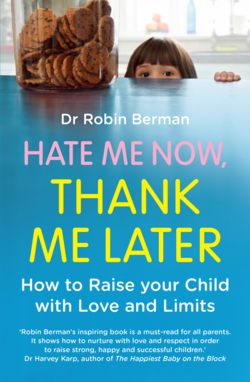

Читать книгу Hate Me Now, Thank Me Later: How to raise your kid with love and limits - Dr. Berman Robin - Страница 7

CHAPTER ONE Hate Me Now, Thank Me Later

ОглавлениеI often ask mums of this generation, “If you got on a plane and saw a four-year-old pilot in the cockpit, how safe would you feel?”

You, not your kids, fly the plane.

—Idell Natterson, PhD, psychologist

If you want to learn about parenting, head to Starbucks. You don’t have to wait too long before you see a child melting down. Oh, and there he is: an adorable four-year-old boy with curly blond ringlets. Adorable, that is, until he opens his mouth to whine and negotiate for a cookie and chocolate milk, in spite of his mum’s repeated requests to pick one or the other.

Immediately the rest of us in line transform into the parent police, secretly hoping that the mum will hold her ground, but knowing deep down that she won’t. I feel as if I am rooting for the underdog in this power struggle, and her name is Mummy.

We grow more and more uncomfortable as the tantrum escalates. “I want both, you can’t make me pick one. You are a mean mummy!” Everyone in line rolls their eyes at each other, and, at this point, I have to control my instinct not to intervene. I get up to the counter to order my latte and the boy smiles at me victoriously, holding his cookie and chocolate milk. I smile back, thinking, I will see you on my couch in twenty years.

Why is this such a common scene in today’s parenting culture? Why is this generation of parents being emotionally bullied by their children? Kids are holding their parents hostage. Children used to be seen and not heard, but now they are the center of the universe. It is clear that the parenting pendulum has swung too far, and, in between these two extremes, we just might find a graceful new middle.

Parents today seem skittish about asserting their authority. I get it. These are the parents who vowed never to hit their kids as they had been hit and not to rule by an iron fist. Great instinct, but don’t you think that we have gotten a little carried away? The parental power structure has gotten off-kilter. Parents today seem afraid to assume their rightful position as captain of the ship. If there is no captain, the ship will not sail, or, worse, it will sink.

I often want to take out my prescription pad and write: “You have my permission to parent.”

Other physicians offer similar prescriptions.

“Parenting is an autocratic system, it is not a democracy. Children need to follow rules or else they become unruly.”

—Lee Stone, MD, pediatrician

“Kids want to feel as if someone is in charge, as if someone is protecting them. Don’t be afraid to assert what you think is right for your child. Don’t be afraid to be in charge.”

—Daphne Hirsh, MD, pediatrician

“Parenting is a benevolent dictatorship.”

—Robert Landaw, MD, pediatrician

“Don’t let the inmates run the asylum.”

—Ken Newman, MD, psychiatrist

Today too many little inmates are clearly running the show. The truth is, if you pander to your child’s worst behavior, that is exactly what you will get.

At a birthday party, a seven-year-old girl went up to the host and asked if there was going to be ice cream with the cake, and if there was chocolate chip. In a frenzy of party chaos, the host mum mumbled, “I think so.”

When it was time to sing “Happy Birthday to You,” Suzie began pestering the mum: “I want that ice cream,” she demanded. The host mum’s feathers were already ruffled; there was no “please,” no “excuse me.” She pulled out a tub of cookie dough ice cream and began to scoop it onto Suzie’s plate.

“That is not chocolate chip,” Suzie yelled, growing increasingly agitated. “You said that you had chocolate chip, and this is cookie dough. I don’t like cookie dough!”

The host mum calmly explained, “I am sorry, I made a mistake. I thought it was chocolate chip. You can either have that or a Popsicle.”

Of course, you know what came next. And it is not the fantasy we all were hoping for, the one in which Suzie’s mum calmly intervenes and says she understands that her child is disappointed, but that she has two choices of desserts, and the third choice is to leave the party if she can’t contain herself. All the parents at the party are secretly rooting for the “leave the party” option.

“I don’t want a Popsicle, and I don’t like the cookie dough pieces!” Suzie screamed.

All eyes turned to Suzie’s mum as she walked over to her daughter. The drama of the scene completely upstaged the birthday boy as the mother tried to cajole her child. She began with, “Oh sweetie, my love, angel, cookie dough is really good, do you want to try some?”

The child looked angry. Her mother continued, “You love Popsicles—how about an orange one?”

“No,” Suzie wailed. “I want chocolate chip!” All eyes went back to Suzie’s mum, our necks straining like spectators at a tennis match, hoping she could lob a winner.

Suzie’s mum shocked us all. Instead of calmly asserting her parental authority, she frantically started picking out the pieces of cookie dough and putting them in her mouth, attempting to be a human pacifier. I felt as if we were being punk’d. We waited and waited. But Ashton Kutcher never came.

It is not safe for a child to have that much power. Parents seem to be tap-dancing faster and faster to try to placate their children rather than setting clear limits and asserting their authority. When you find yourself constantly bribing and negotiating, you can be sure the power structure has run amok.

The bottom line is that kids with too much power feel unsafe. Children with too much influence often become anxious because they feel like they have to control their environment, and they really don’t know how. This stress triggers a cascade of toxic neurochemistry. Creating situations in which a child’s developing brain is consistently bathed in the stress hormone cortisol is not a wise parenting move.

I have treated my share of anxious adults. One patient described it perfectly: “I felt sleazy being able to so easily manipulate my parents as a kid. It felt unsafe.”

Parents today seem to have trouble tolerating their children’s unhappy emotions. You must be able to withstand your children’s disappointments and negative feelings without rushing in to fix them, or you unintentionally will be crippling your children. If you can’t handle their negative feelings, how will they learn to?

Your task as a parent is to help your child self-soothe. You need to help your child build an emotional immune system. A vaccine inserts a little bacteria or a virus into your bloodstream so that you can build the immunity to fight the big one when it comes along. Think of helping your children work through negative feelings, rather than trying to fix them, as providing an emotional vaccine. You are arming them with an emotional booster for the future.

Parents who never want their kids to be upset with them, and who avoid their children’s disappointment at all costs, are doing their kids a huge disservice. Good parenting can make you temporarily unpopular with your kid. Keep thinking, Hate me now, thank me later. Isn’t creating a resilient adult worth enduring a few sniffles now?

Consider the message that Suzie’s mother was teaching her: “If you are unhappy, whine louder to get your way. Your needs usurp all others’ in the room.” Fast-forward on little Suzie. Would you want to date her? Her future might be a string of one-and-dones.

By being too nice, we are actually being mean. It takes courage and some gumption to do the right thing. Take comfort in knowing that Authoritative Parenting—defined as listening to your child, encouraging independence, and giving fair and consistent consequences—yields very well-adjusted children. Spoiling a child is easier in the moment than setting limits, but it is your job to help regulate and contain your children’s emotions. Emotionally wimpy parenting leads to emotionally fragile kids.

“My problem is, my kids know that my no means maybe.”

—Mother of three

“You can’t parent by the path of least resistance.”

—Marc, divorced dad

“The only way to make adulthood hard is to make childhood too easy.”

—Betsy Brown Braun, parenting educator and author

Parents today have way too long a fuse for bad behavior. Some mums seem to have an inordinate amount of patience for withstanding endless negotiations and tantrums, making them seem almost like Stepford Mums. A child whines and negotiates ad nauseam, and parents just keep on listening.

“I mean, how many more ‘if you do that one more time’s can we hear from this generation?”

—Kari, grandmother

What shocks me is how charmed parents are when their kids negotiate. They seem delighted by their kids’ smarts rather than drained by their relentless lobbying. Life’s simplest tasks, like going to bed or leaving the park, become fifteen-minute arguments. It is exhausting.

The power structure has capsized, and many kids are drowning. They are talking faster and faster to get their way, and it is stressful for everyone. Parents constantly ask me how to restore order.

The best way to stop a little debater in his tracks is a tool I call reverse negotiation. It works like a charm. Here is how it is done: you tell your child that negotiating will no longer be tolerated. If you are thinking that it’s not that simple, you would be right. But wait, there is more—you add that when your child negotiates, not only does he not get what he was asking for, but he gets less than what he started with. Let’s give it a whirl:

PARENT: Bedtime is at eight.

CHILD: I want to stay up until eight thirty.

PARENT: No, it’s eight.

CHILD: I want to stay up later.

PARENT: Now bedtime is seven forty-five.

CHILD: Fine, I’ll take eight.

PARENT: Now bedtime is at seven thirty.

You must stick to this revised bedtime. Cement it in, no parental trade-backs. Don’t be the parent who cried wolf. Aaaah . . . Silence. All is quiet, all is well. It is as if suddenly you turned off the music on a grating radio station. If you really follow through, the little debater will vanish, and in his place will be a lovely child, snuggled in his cozy pajamas and ready for bed. Poof! Magically, the endless “if you do that one more time” tune is no longer playing in your head.

“Sometimes love says no.”

—Marianne Williamson, spiritual leader, author

Ways to Think about No. Shrink-Tested and Mother-Approved

No.

No is a complete sentence.

No, that’s my final answer.

No does not begin a negotiation.

No cannot mean “maybe.”