Читать книгу Art of Islam - Gaston Migeon - Страница 18

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

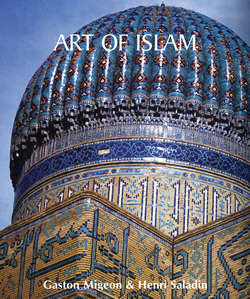

Architecture

B – North Africa and Spain

The Great Mosque of Tlemcen

ОглавлениеThe beginning of the 11th century marked a period of prosperity for Tlemcen, whose beautiful monuments, especially its mosques, are masterpieces of Islamic art. This great mosque (1135–1138) is a clear example of Maghrebian architecture. The widest of all the parallel naves, the central one, is accessible through a large gate whose matchless beauty shows the way to the sanctuary. At Mansurah, close to Tlemcen, the mihrab forms a kind of small tower. Inside the mosque is a sanctuary even more precisely highlighted than in the mosque at Córdoba. The minarets of both mosques are on a square plan. To this present day, every Maghrebian mosque is equipped with parallel naves, with a central nave, a richly ornamented porch, a turret-like mihrab and a minaret on a square plan.

The minarets are decorated with a sort of network which is logical given that the goal was to make the wall lighter and firm at the same time using this rigid brick decoration. These bricks are often glazed in order to create a delicate effect. It is quite likely that these glazed ceramic bricks are of Mesopotamian and Persian origin. The ornamentation of the Momine Khatun Mausoleum in Nakhchivan (1186) has some similarities with the one in Zaragoza). As soon as the Maghrebians discovered the manufacturing of glazed ceramics, they replaced the porphyry, granite and marble they had used for paving and casing with this bright and economic material. With regard to faience mosaics, each piece was manually cut into tiles and then filed or moulded into shape and adapted to its neighbour, following a section tilted toward the exposed face in such a way as to ensure the joint is firm; this technique is still used in Fez. It was only later that ceramists, following a slightly coarser technique, moulded the different pieces to be assembled, or better still, added lines or reliefs to the tiles to show their polygonal harmony.

The toothing of the arches in the Great Mosque of Tlemcen shows the extent of lavishness that characterised Islamic architecture. These indentations could be imitations of some forms of wooden architecture that may be understood better if one studies the consoles of great Arab canopies in the Alcázar in Seville or some monuments in Marrakech, Meknes and Fez. In my opinion, these indentations – especially those that are small and regular – are the result of using bricks in construction. Indeed, it is preferable for brick arches to have intersecting joints, and it is important to coat them by reducing the intervals that exist between the longest and the shortest bricks found in the intrados of the arch.

The mihrab of this mosque is an architectural masterpiece. Its rectangular framework suits the alternatively smooth and sculpted arch whose archivolt is beautifully silhouetted in successive lobes. The dome surmounting it is beautifully decorated with pierced shapes.

The building of such monuments also flourished during this period in Spain and Morocco under the guidance of Almoravid and Almohad rulers, who had united these two countries under their power. This was presumably a classical era. The relatively severe decoration and the simple and vigorous plans comprise the major features of a layout with excellent proportions.

Prayer hall in the Great Mosque of Córdoba, 785–988.

Córdoba.