Читать книгу Art of Islam - Gaston Migeon - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

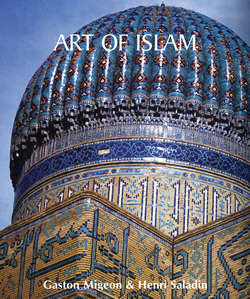

Architecture

A – The Near and Middle East

Cairo

ОглавлениеRather than the lavishness of materials used, the beauty of early Egyptian mosques sprang from painting, gilding and tapestry hangings. For example, the Tulun Mosque, one of the oldest in Cairo, is made solely of plaster-coated bricks. In Syria, Damascus and Jerusalem, however, the rich decoration does not have similar characteristics: precious marbles, metals and enamel mosaics were used in construction. Marble columns, capitals and bases, marble or mosaic coverings, bronze doors, painted and gilded ceilings, beams covered in sheets of embossed and gilded bronze… all were used both as construction materials and as decoration. It was thus an application of Roman and Byzantine methods, but with an entirely new spirit in the general layout, which was distinctly defined by lavish decoration.

The representation of human figures was not completely banned in early Muslim art. Statues, bas-reliefs and tableaux were frequently seen in the palaces of monarchs or prominent individuals. Unfortunately, all we have are documents that enable us to imagine the likely layout of these edifices: no existing vestiges can hint at the possible features of the palaces of both Ibn Tulun and his son, Khomarouyeh, of which Makrisi provides interesting descriptions.

Introduced in the 13th century, the cruciform plan became so typical that it was used even in small mosques. Syrian influence was already becoming evident in the construction of religious edifices under the Fatimids, and we will find that influence more present in the fortifications of Cairo; the architects who constructed the three large entrances of the Badr El-Gemali compound were from Edessa, and therefore Syrians.

Although the unorthodox features of this eastern influence disappeared when the Ayyubids replaced the Fatimid dynasty in Cairo in the second half of the 12th century, the influence of Syrian methods was becoming common, especially in the construction methods Egypt had adopted. The use of stone, complex devices and multicoloured decorations with marble or coloured stones, both of them of Syrian origin, spread quickly and grew to include not only religious but civil architecture as well.

This influence, which was first felt under the Fatimids and subsequently under the Ayyubids, further increased under the Mameluke-Baharite sultans (from 1250 to 1382) and reached its climax under the Mamelukes (1382–1515).

Turkish conquerors introduced the Ottoman dome-shaped mosque in Cairo to emphasise their control by imposing a stamp on religious edifices. While the conquerors were hailed as supreme caliphs and Muhammad’s assistants by all Sunni or orthodox Muslims, their rule was not absolute: many small mosques in Cairo maintained the traditional design, even after 1516. However, the Ottoman occupation had no effect whatsoever on civil and domestic architecture.

Ablution fountain, 1363.

Sultan Hassan Mosque, Cairo.

Courtyard of the Ibn Tulun Mosque, 876–879.

Cairo.