Читать книгу Art of Islam - Gaston Migeon - Страница 26

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Architecture

C–Iran and the Persian School

Ornamentation

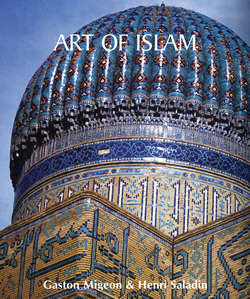

ОглавлениеFaience was the most luxurious component of architectural decoration in Persian buildings. Initially reduced to the size of enamelled bricks, contrasting with the pink background of baked bricks or the white tone of stuccos (Momine Khatun Mausoleum in Nakhchivan), enamelled decoration soon became very common in brick masonry. Then, in an attempt to create something different using drawings with rectilinear components, which is possible only with bricks, small enamelled fractions were cut and juxtaposed to create beautiful decorations of a faience marquetry, a kind of opus sectile that can be used alone or alongside baked bricks. The use of different types of enamelled terra-cotta tiles, whose juxtaposition allows for drawings or accurately glazed components in turquoise blue with reliefs, alternating with lustrous elements on a creamy white background, was initially used for sub-standard decoration, on panellings and mihrabs. In the 14th and 15th centuries, the palette of ceramists steadily improved, drawings became more complex, and finally, at the beginning of the 16th century in Ardebil, Sheik Sefi’s tomb was decorated with a wide range of possible applications of architectural ceramics: cornices with stalactites, fascia boards, friezes with inscriptions and enamelled brick domes. Buildings that were constructed or restored in Isfahan during Shah Abbas’s reign are also wonders of ceramic ornamentation, but the indiscriminate use of wall tiles is one of the main reasons for the dilapidation of these buildings. Abandoned without any maintenance and with the changing Persian climate, these coverings gradually fell off, and monuments less than four centuries old lost their adornment in a few years. Colours became more and more varied in the 17th century. Pink, light yellow, red and green added to the range of colours that were initially used: turquoise blue, brown, reddish brown, dark green, cobalt blue, white, violet and black. The decorations originally looked like carpets, then like the human figure, scenes with people, animals, and then real flowers were gradually introduced into this disarray, which quickly led to the decline of this beautiful art. Coloured stained-glass windows set in structures of cut plaster, friezes made of sculpted or moulded plaster or stuccos, precious wood inlays, precious metals, gildings, and later glass from Venice, paintings and impressive stars stitched with gold or silver – all these elaborate crafts added to the collections which we only know vaguely, either through the descriptions of travellers who did their best in describing what they had seen, or through books in which the presentation of these buildings and their decoration was often very vivid.

In Persia, whose pre-16th century edifices are known today as exclusively religious or public buildings, there are still the palaces of the Safavid kings and their successors, as well as those of the main Persian lords that date back to the 17th century. Based on these examples, we can still clearly appreciate the splendour and taste of Persian courts as they were and see these ancient luxurious wonders that we know only through history books constructed today, as it were.

We have seen the reasons that make us point to Mesopotamia as the cradle of Islamic architecture in Persia. As for monuments in Turkestan, they cannot be studied separately because they demonstrate a strong Persian influence: some buildings in Samarkand and Bukhara were erected by Persian architects from Shiraz or Isfahan. It would be very difficult to draw any kind of analogy between them, and to attribute all of them to a so-called Seljuq style, since Ottoman art is different from that of Persia, from a strictly architectural point of view.

These foreign dynasties sometimes fairly contributed to modifying local styles by encouraging more frequent interactions between the peoples they united under their rule; by introducing the taste of enamelled coatings, as did the Seljuqs of Anatolia; by seeking to find, in the monuments that they were erecting in Edirne, some of the aspects of this luxurious decoration that they had admired in Persia; or by creating substantial colonies of Chinese ceramists, whose influence is clearly established by some details of faience coating used as ornamentation and tonality for coloured enamels. This is what Hulagu and Tamerlane did for Persia and Samarkand respectively.

The Mosque of Samarra is known for its imposing minaret. It was designed on a square foundation, where the tower itself is erected with its spiral staircase, which tapers to a sort of cone. It includes six revolutions, and the tower is 50 metres tall. The pillars are rather similar to those of El-Achik, though smaller in diametre. Samarra has three huge palaces: El-Gauchak, El-Oumari and El-Waziri constructed by Montassim, el-Haruniye constructed by Harun el-Walid, an artificial hill and a hippodrome. Upon Moulaouakil’s death, his successor abandoned Samarra, and its inhabitants were forced to leave their homes, taking along their furniture, beams and the doors of their houses.

The Tikari madrasa, Samarkand.

Kalyan Minar, 1127, Kalyan Mosque, 16th century, Miri Arab Madrasa, 17th century.

Bukhara.

The Poi Kalon complex, 12th-20th centuries.

Bukhara, Uzbekistan.