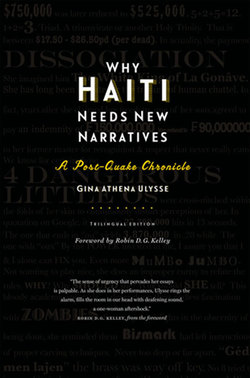

Читать книгу Why Haiti Needs New Narratives - Gina Athena Ulysse - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFOREWORD Robin D. G. Kelley

We say dignity, survival, endurance, consolidation

They say cheap labor, strategic location, intervention

We say justice, education, food, clothing, shelter

They say indigenous predatory death squads to the rescue

— Jayne Cortez, “Haiti 2004”

The longer that Haiti appears weird, the easier it is to forget that it

represents the longest neocolonial experiment in the history of the West.

— Michel-Rolph Trouillot, “The Odd and the Ordinary: Haiti, the Caribbean, and the World”

In my circles, there are two Haitis. There is Haiti the victim, the “broken nation,” the failed state, the human tragedy, the basket case. Depending on one’s political perspective, Haiti the victim was either undermined by its own immutable backwardness, or destroyed by imperial invasion, occupation, blockades, debt slavery, and U.S.-backed puppet regimes. The other Haiti, of course, is the Haiti of revolution, of Toussaint, Dessalines, the declaration at Camp Turel, of C. L. R. James’s magisterial The Black Jacobins. This is the Haiti that led the only successful slave revolt in the modern world; the Haiti that showed France and all other incipient bourgeois democracies the meaning of liberty; the Haiti whose African armies defeated every major European power that tried to restore her ancien régime; the Haiti that inspired revolutions for freedom and independence throughout the Western Hemisphere. Rarely do these two Haitis share the same sentence, except when illustrating the depths to which the nation has descended.

Gina Athena Ulysse has been battling this bifurcated image of Haiti ever since I first met her at the University of Michigan some two decades ago, where she was pursuing a PhD in anthropology, focusing on female international traders in Jamaica. Then, as now, she was an outspoken, passionate, militant student whose love for Haiti and exasperation over the country’s representation found expression in everything else she did. She had good reason to be upset. Both narratives treat Haiti as a symbol, a metaphor, rather than see Haitians as subjects and agents, as complex human beings with desires, imaginations, fears, frustrations, and ideas about justice, democracy, family, community, the land, and what it means to live a good life. Sadly, impassioned appeals for new narratives of Haiti do not begin with Ulysse. She knows this all too well. Exactly 130 years ago, the great Haitian intellectual Louis-Joseph Janvier published his biting, critical history, Haiti and Its Visitors—a six-hundred-page brilliant rant against all those who have misrepresented Haiti as a backwater of savagery, incompetence, and inferiority. With passion, elegance, grace, and wit matching Janvier’s best prose, Ulysse’s post-quake dispatches and meditations about her beloved homeland demolish the stories told and retold by modern-day visitors: the press, the leaders of NGOs, the pundits, the experts. Of course, it is easy to see how the devastation left by the earthquake would reinforce the image of Haiti-as-victim, but representations are not objective truths but choices, framed and edited by ideology. Poor refugees sitting around in tent cities, a sole police officer trying to keep order, complaints over the delivery of basic foodstuffs and water—this is what CNN and Time magazine go for, not the stories of neighborhoods organizing themselves, burying the dead, making sure children are safe and fed, removing rubble, building makeshift housing, sharing whatever they had, and trying against the greatest of odds to establish some semblance of local democracy.

Ulysse is less interested in “correcting” these representations than interrogating them, revealing the kind of work they do in reproducing both the myth of Haiti and the actual conditions on the ground. Now. The sense of urgency that pervades her essays is palpable. As she does in her performances, Ulysse rings the alarm, fills the room in our head with deafening sound, a one-woman aftershock. We need this because the succession of crises confronting Haiti throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries inured too many people to the unbearable loss of life—some three hundred thousand souls perished in the earthquake on January 12, 2010. Here in the United States, when ten, fifteen, twenty die in a disaster, the twenty-four-hour news cycle kicks into high gear. But in Haiti, these things happen. Ulysse wants to know how we arrived at this point, when Haiti is treated much like the random bodies of homeless people, whose deaths we’ve come to expect but not to mourn. The problem is not one of hatred, for who among us sincerely hates the homeless? It is indifference. As the late actor/poet Beah Richards often said, “The opposite of love is not hate, but indifference.” Indifference produces silence. Indifference ignores history. Indifference kills.

Like many Haitians, she understands that the two Haitis do not represent polar opposites or a linear story of descent. Rather, they are mutually constitutive, perhaps even codependent. The condition of Haiti is a product of two centuries of retaliation for having the temerity to destroy slavery by violent revolution, for taking the global sugar economy’s most precious jewel from the planters, traders, bankers, and imperial rulers, and for surviving as an example for other enslaved people. The war did not end when Jean-Jacques Dessalines declared Haitian independence on January 1, 1804. Remember that the war left the country’s agricultural economy in shambles; its sugar-processing machinery had been destroyed, along with its complicated irrigation system. And even if the people wanted to return to growing cane for export, the Western powers established naval blockades and refused to trade with the new nation in a failed effort to choke the life out of the revolution. Unable to reimpose chattel slavery, they turned to debt slavery. In 1825, the French forced Haiti to pay 150 million francs as reparations for the loss of “property” in slaves and land. No Haitian families were compensated for being kidnapped, forced to work for low wages, wrongful death or injury, etc. Although the French magnanimously reduced the principal to 90 million francs thirteen years later, the indemnity nevertheless cleaned out the Haitian treasury and forced the country into debt to French banks. The banks profited from the debt and quite literally held the mortgage on Haiti’s future. Indeed, the payment to France and French banks amounted to half of Haiti’s government budget by 1898; sixteen years later, on the eve of the U.S. occupation of Haiti, the debt payments absorbed 80 percent of the government’s budget. By some measures, what Haiti eventually paid back amounted to some $21 billion in 2004 dollars.

A life of debt and dependency on a global market was not the political or economic vision the Haitian people had in mind. They owed the West and their former enslavers nothing. The land belonged to them, and the point of the land was to feed and sustain the people. They grew food, raised livestock, and promoted a local market economy. Yet the rulers of every warring faction insisted on growing for export, even if it meant denying or limiting the liberty of these liberated people. In order to realize their vision, Haiti’s rulers required a costly standing military to preserve the nation’s sovereignty, preserve their own political power and class rule, and maintain a capitalist export economy.

Crush a nation’s economy, hold it in solitary confinement, and fuel internecine violence, and what do we get? And yet, Ulysse refuses to accept the outcome of the two-hundred-year war on Haiti as a fait accompli. Calling for new narratives is not merely an appeal to rewrite history books or to interview the voiceless, but to write a new future, to make a new Haitian Revolution. As her essays make crystal clear, it is not enough to transform the state or dismantle the military or forgive the debt. She writes eloquently about the women, their resilience as well as their unfathomable subordination under regimes of sexual violence and patriarchy. She calls for cultural revolution, for the need to create space for expressions of revolutionary desire, to resist misery, to imagine what real sovereignty and liberty might feel like.

And yet, it would be unfair and premature to call this text a manifesto. She is too humbled by the daunting realities and the trauma of the earthquake, its aftershocks, and the two centuries of history in its wake to make any bold proclamations about Haiti’s future. This text is also about one woman’s journey, a woman of the diaspora who frees herself from exile, negotiating what it means to be a scholar in a world where universities and corporations have become cozy bedfellows; a woman wrestling with a society in which adulthood is reserved for men only; an activist straddling the arts and sciences in a world where “arts and sciences” usually only meet on a university letterhead. Gina Athena Ulysse, like her homeland, simply doesn’t fit. She refuses to fit. And this is exactly why we need new narratives.

We say Haitian water violated

Haitian airspace penetrated

They say kiss my aluminum baseball bat

Suck my imperial pacifier and lick my rifle butt

We say cancel the debt….

They say let the celebration for 200 more years of servitude begin

We say viva the Haitian revolution

Viva democracy viva independence, viva resistance, viva Unity.

—Jayne Cortez