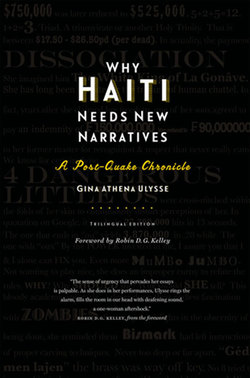

Читать книгу Why Haiti Needs New Narratives - Gina Athena Ulysse - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление7

Sisters of the Cowries, Struggles, and Haiti’s Future

March 18, 2010 / Honorée Jeffers blog / @ Phillis Remastered

December 14, 2009, the day before my last trip to Haiti, I met briefly with an old grad-school chum. P is a sister who also made it through the struggle (of being one of very few) at the University of Michigan, where she earned her JD and I a PhD in anthropology. We overlapped only by so many years as I neared the last stage of the doctorate. We held on to survive the process and now nearly two decades later are working on thriving as professionals.

P and I have more than an alma mater in common; we are also both Haitian-born U.S. diaspora dwellers. We were not close at UM, but we connected. After her graduation, she helped hook me up with an internship in South Africa, where we met up again and bonded. I will never forget upon my arrival in Capetown, P gave me a quick breakdown of local dynamics that ended with her saying “pitit [child with serious emphasis], and then you’re going to find out you are colored” as she broke into sardonic bouts of laughter. Our conversations have always been peppered with Creole words. Another point of connection was the sameness in awareness of our identities and the various social and symbolic politics of being black women.

I sat across from her that Tuesday after several years of intermittent contact. We both marveled at the obvious changes in our state of being and appearances that we recognized as coming from deep within. We did high fives to mark the synchronic moments in our conversation where without question we got each other. “Life is too short.” There were uhmms and uh-huh. “Girl, I am just tired of struggle.” “It’s all about being present.” “I want to live my life now,” we each said. Which comments belonged to either of us hardly mattered. We have been on separate journeys but seemed in many ways to be in the same spot of the crossroads we faced today.

Then I revealed the significance of this moment for me. I was on my way to Haiti and did not tell family members the details of my impending trip, nor did I plan to have or make any contact with my folks in Haiti. I needed to be there as a researcher embarking on the preliminary phase of a new project, not someone’s daughter, niece, or cousin. My reasons were quite simple, as I sought to learn whether I could have a relationship with Haiti on my own terms that were not overshadowed by family dynamics.

Then P made a most definitive statement that resonated with everything I have been struggling with around this journey. I would come back to her words again and again while in Haiti and even now as I write this. She said: “Our culture doesn’t have a space for women to mature and come into our own.” That comment led us into a discussion on what it means to be grown (resurrecting bell hooks) as women when we do not possess the primary marker of adulthood (children).

How do we transition from girl to woman to wise one? She had been married, and I remain single. Those of us who take nontraditional roads are continually reminded there is no point of reference for us. Yet we also know that who we seek to be stems from deeper desires to come to terms with ourselves as fuller beings made in our own visions. We are not like our mothers or grandmothers. We are engaged in conscious acts of self-making as we resist the urge to be crunched up into other people’s fantasies for us, as Audre Lorde has written.

The next time I saw P was several weeks later. January 12, 2010, is the day part of the earth had cracked open in the Western Hemisphere and fractured our beloved country of birth, only to reveal its most persistent inequities and vulnerabilities. We tried to squeeze every concern we had into the fifteen minutes she was available. I needed to reconnect with her before facing an audience of strangers. At times, we shook our heads in disbelief and shared continuous repetitions of the word pitit that needed no explanations.

Then our attention turned to the planeload of the very young, labeled “orphans,” who were whisked off to foreign lands. “I called my mother and even said I would take a couple and bring them home,” P said. We scrambled for words to reflect our outrage and still make sense of this desperate act. What is the value of Haitian children? The worse was yet to come as we discussed the dead. The uncounted. The mass graves.

Where are the Haitian voices on this issue? Why so many artists? How can the president remain silent throughout this moment? The conversation turned to our commitment to helping in recovery somehow, as it is our duty to do so. Then we realized we had not talked about my trip to Haiti. I gave her a brief reply in minutes and told her I had been writing op-eds for sanity and to make sense out of this moment.

The thing about P is that she too is at a point in her life wherein she refuses to be silent. Weeks later, I encountered another woman of Haitian descent, Lenelle Moïse at Northwestern University. She was scheduled to perform Womb Words Thirsting—an interactive autobiographical one-woman show that mixes “a brew full of womanist Vodou jazz, queer theory hip-hop, spoken word, song and movement.” I was there to respond to the work and write a critique for the Performance Studies Department’s project Solo/Black/Woman.

On the ride from the airport, Haiti was the center of our discussion. Status of family … friends. Where we were when we got the news. We also talked of our worries and the disconcertment of bearing witness from so far away. What of Haiti’s future since it seems that the players remain the same?

This was Moïse’s first performance since 1/12. When she took the stage a day later, it was evident that those who dare to break the structure of silence are needed now more than ever. Beyond her grace, there was rage; though this work had been written years before, it bellowed screams for a Haiti that desperately needs fierce and persistent advocates on the front line at home and abroad. Moïse took risks to stake claim to a self while determined to live a full life.

Some of our struggles here are so distant from those back there. This fullness, this idea of a sense of self as whole that we seek has historically eluded Haiti, or people’s perceptions of and representations of Haiti. As we obsess over Haiti’s future and our potential roles in it, we do so knowing we are in a place of such privilege.

Since the quake, in the tent cities that have sprouted all over the capital, women and girls are the most vulnerable. They are susceptible to sexual exploitation, harassment, and rape. Discussions concerning reconstruction efforts tend to ignore the specific situation of women. Activists here and there are trying to put women’s issues on the table. Many of us are only too aware of how crucial it is that the needs of women not be ignored. Haitian women have been known as the potomitan—center pillars of their families and communities. Without their wellness, whole selves, and protection, Haiti’s future will remain an abstraction lost in theory.