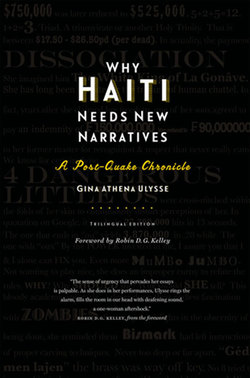

Читать книгу Why Haiti Needs New Narratives - Gina Athena Ulysse - Страница 21

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление9

Haiti’s Earthquake’s Nickname and Some Women’s Trauma

April 12, 2010 / Huffington Post @ 11:23 a.m.

The earthquake that decimated various parts of Haiti on January 12, 2010, has a name. Goudougoudou—that’s the affectionate moniker that Haitians have given the disaster. Everyone uses the term. It is as popular with radio show hosts as it is with people on the street and others in offices. There are several jokes, ranging from mild to the spicy, about what to do in the event of another reprise of Goudougoudou, especially while you are engaged in any kind of private activity, from using the toilet to making love. Whatever you are doing, stop and make a run for it to the clear.

An onomatopoeia, Goudougoudou mimics the sound that the buildings made when the earth shook everything on its surface and leveled those that were not earthquake proof. The mere mention of the word is sometimes followed with a smile or even bits of laughter. Goudougoudou doesn’t sound nearly as terrifying as the experiences that most folks will recount when you ask them where they were that afternoon when it happened.

Sandra would not tell me her story at first. I heard it in detail from her mother, Marie, whose voice rose several decibels when she recalled her horror: “Sandra was alone in the city. She went there to register for a course. She had just left the school building, crossed the street to take a tap-tap. She saw it collapse with everyone still in it.” The school was close to the Christopher Hotel (where MINUSTAH was based). Both structures collapsed. Sandra became hysterical during the entire drive home. A woman on the bus threw a piece of cloth over her eyes so she would not witness any more. Buildings were still crumbling, crushing bodies as she made her way home.

When Sandra finally spoke to me, it was an abbreviated version. She focused more on a former classmate who had been buried under the rubble for several days. Along with her family, she was bused out of the capital into the provinces. Since the classmate’s return, she has not been the same. When you look at her, Sandra says, it’s like looking at someone who is no longer there. Her eyes are open, but she is not there.

Maggie could not wait to tell her story. She was in the city with her niece. They both fell down. With her wiry frame, she used every part of her body to re-create the moment. She said, “I didn’t know what was happening. The thing dropped me on the ground, pow! flat on my belly.” As she explained it, “I tried to stand. It dropped me down again and pow!” showing where each arm landed.

Micheline was inside the house. Her father rushed in to retrieve her where he found her standing disoriented. Subsequently, with each aftershock, she became more clingy, crying, screaming, asking her father if it will happen again.

Since Goudougoudou, the women refused to sleep indoors. So the men built a tin-roofed shack in the yard, where everyone still sleeps at night. Those who dare to remain under the concrete, as folks say jokingly, call themselves soldiers. For the kids’ sake they call the shack a hotel. Micheline’s biggest thrill is going to the hotel at night. In the dark, she rushes to it, where she will snuggle next to her brother, her best pal, and a slightly older cousin. When I arrived in Haiti for my first trip since the quake, one of Micheline’s first questions to me was will I sleep in the hotel?

When I asked her about Goudougoudou, she smiled with the brazen timid defiance of a four-year-old who had no intention of answering me. These are stories of a couple of women in my family. Other folks I encountered were not as inclined to be silent. Whoever I asked began to tell their stories, often all at once—each one too often more horrid than the next. The need to speak the trauma and fright they have lived is a psychological one that must be addressed, as it is so necessary for healing.

The government is fumbling with its incapability to deliver and coordinate even the most basic needs as NGOs run amok in country; mental health needs are not a priority. While there are ad hoc efforts to address the trauma, especially among children, it is clear that what is necessary is a coordinated project at the national level to ensure that the post-traumatic stress of Goudougoudou does not remain trapped in the bodies of those who lived this moment and its continuous aftermaths.