Читать книгу Why Haiti Needs New Narratives - Gina Athena Ulysse - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION NEGOTIATING MY HAITI(S)

A taste for truth does not eliminate bias.

—Albert Camus

It has become stylish for foreign writers to denounce Haiti’s

bad press while contributing to it in fact.

—Michel-Rolph Trouillot

Many years ago, when I was a graduate student, a Haitian professional (also living in the United States) reproached me for identifying as Haitian-American. In the extremely intense debate that ensued, I found myself staunchly defending the embrace of the hyphen with full knowledge that because of history, my two joined worlds have not been and would never be equal. I strongly believed my identity was not reducible to its point of origin. What I did know then, and I am even surer of now, was that Haiti was my point of departure, not my point of arrival.1

At the time, a moment best characterized by what writer Edwidge Danticat refers to as the post-Wyclef era,2 the consequences of identifying as Haitian in some circles (for example, the academy where I have spent a lot of time) were less hostile or, I should say, had their particular version of hostility. Regardless, the reason I insisted on my Americanness was not shame, as this person presupposed and even verbalized, but a rather simple mathematical equation.3 If I counted the number of years I resided in my pays natal and the number of years spent outside it and in Haitian circles, they would add up to over nineteen. I lived in Haiti for eleven years. Moreover, because of several accumulated years of extensive fieldwork in Jamaica, coupled with other travels and so many different experiences, I was aghast at being boxed in personally, as well as (with notions of essentialism) socially.

The Haiti in the Diaspora

My Haitianness, if you will, was never questionable to me, because I had spent years critically investigating issues of identity as both social and personal phenomena. The social analysis confirmed the individual examination, leading me to realize and make peace with the fact that I would always be part of two Haitis. There was the one that, due to migration, was being re-created in the diaspora, and the one in the public sphere that continually clashed with the one in my memory. Or perhaps there were three Haitis. In any case, the Haiti I left behind was one that was changing in my absence, while the one I lived in, as a member of its diaspora, had elements of stasis, as it was couched in nostalgia. Hence, I live with a keen awareness that negotiating my Haitis inevitably means accepting that there are limits to my understanding, given the complexity of my position as both insider and outsider. Finally, because the Haiti of my family and the socioeconomic world I grew up in encompassed such a continuum of class and color and urban and rural referents, Haiti and Haitians historically have always been plural to me.

These contemplations not only have concrete effects on my relationship with Haiti but also the role I play as a Haitian-American determined to be of service to her birth country somehow. That said, this book, in a sense, is the result of a promise made long ago at the tender age of eleven, when I came to live in the United States. Upon first encountering the Haiti that exists in the public sphere, I had just enough consciousness to vow that I would never return to Haiti until things changed. Of course, I eventually changed my mind.

This decision to go back, which I have written about ad infinitum, reveals as much about my personal journey as it does my professional one. With more time, the two would intertwine in curious ways, never to be separated, as I embraced yet another set of hyphens, this time as artist-academic-activist. These identities would become increasingly distinct, especially as I transitioned from relying less on the social sciences and more on the arts. Moreover, irrespective of my chosen medium, I was already out there as a politically active and vocal member of Haiti’s “tenth department.”4

Out There in the Public Sphere

I often say I did not set out to “do” public anthropology,5 but that’s not exactly true. It’s also not a lie. The fact is I decided to seek a doctoral degree in anthropology for a singular reason, Haiti. I became progressively frustrated with simplistic explanations of this place that I knew as complex. I became determined to increase and complicate my own knowledge of Haiti, always with the hope of eventually sharing what I learned with others.

My plans did not immediately work out as intended; I ended up doing my dissertation research on female independent international traders in Kingston, Jamaica. Yet once I began to teach, I regularly offered a seminar that sought to demystify the Haiti in popular imagination, and to help students envision a more realistic one. Besides that course, for many years, my anthropological engagement with Haiti was off the grid of my chosen professional track. It was the subject of my artistic pursuits—poetry and performance—and the focus of occasional reflexive papers I presented at conferences. That changed drastically one day in January 2010.

My transformation was punctuated by the fact that one month before that afternoon, I did the unthinkable: I set out on a trip to Haiti for the first time without informing my family. As an artist, and a self-identified feminist made in the Haitian diaspora, I was curious about the impact of migration. I experienced it as a rupture, and I continuously wondered about my personal and professional development—whom I might have become had I remained in Haiti. The plan was to go there and see if it was possible for me to have a relationship with Haiti that was entirely mine.

Where exactly would I fit?

Three weeks after I returned, circumstances would not only force me to rethink that question, but thrust me into the public sphere in the shadow and footsteps of other engaged anthropologists who resisted the urge to remain in the ivory tower. As fate would have it, I had already taken calculated steps to get there.

“Write to Change the World”

That’s the tagline of the one-day seminar I attended in October 2009 at Simmons College in Boston. Among other things, the Op-Ed Project sought to empower women with the tools and skills needed to enter the public sphere as writers of opinion pieces. The premise was to engage the fact that upper-class white men submit more than 80 percent of all published op-eds. The project worked to change these statistics by showing women, especially, how to write and pitch to editors. I remember pondering the reality of the remaining 20 percent, inevitably white women and a few minorities. As a black Haitian woman, I wasn’t even a decimal point.

I had briefly dabbled in this medium before. In 1999, fresh out of graduate school, I wrote “Classing the Dyas: Can the Dialogue Be Fruitful?”—a piece about returning to Haiti from the diaspora and the brewing tensions with those who live at home. It was published in the Haitian Times. Nearly a decade later, I penned another piece, this one on Michelle Obama, which appeared in the Hartford Courant days before the 2008 elections. The newspaper editor’s headline, “Michelle Obama: An Exceptional Model,” topped my piece instead of my feistier “She Ain’t Oprah, Angela or Your Baby Mama: The Michelle O Enigma.”

I was always interested in having my say; I have been labeled opinionated (not a compliment). It is a fact that black women who speak their minds have historically been chastised for “talking back.” In that sense, I am not at all special. Since I did not possess the know-how necessary to negotiate this world of opinion pages, I sought to understand it from an insider’s perspective. So I signed up for Simmons’s seminar.

I learned not only how mainstream media functions, but also how gatekeepers operate—the importance of networks and connections. Most importantly, I gained critical insights on how notions of expertise are socially constructed, what is required to increase readership, and how to expand one’s “sphere of influence.” While seminar participants were encouraged to put newly acquired skills to the test, I was not inspired to write an op-ed until early the following year. Still, this experience did motivate me to keep on learning.

To that end, in December 2009, I applied and was selected for the Feminist Majority Foundation’s Ms. Magazine Workshop for Feminist Scholars—a three-day boot camp that trained activist-oriented academics to become public intellectuals. The intent was quite specific: Ms.’s ultimate goal was to show us how to put our academic knowledge to work by making it more accessible to the public. Participants were also encouraged to write for the Ms. magazine blog, which I eventually began and continue to do intermittently.

From both of these seminars, I not only obtained critical understanding of my voice and style, but also saw how and where aspects of my nuanced perspective might actually fit in the world of fast media. Although quite scary at first, the best incentive was the knowledge that I would be restricted to limited space (five to seven hundred words maximum) and had to gain a reader’s attention quickly, often in just the first sentence. This new approach to writing meant undoing earlier academic training, eschewing professional attachment to the value of jargon-laden prose and a method of slowly developed storytelling that emphasized covering all bases. While it was challenging, it was also freeing to use my ethnographic eye and sensibilities to creatively unpack cultural complexities knowing the endpoint was to introduce readers to potentially alternative views. With more experience, I really liked this medium.

No Silence after the Quake

My first op-ed was a commentary on James Cameron’s blockbuster film Avatar. I used the Op-Ed Project mentor-editor program to get feedback before pitching my piece, “Avatar, Voodoo, and White Spiritual Redemption.” I discussed various aspects of the film, including its connection to New Age spiritualism, which hardly ever incorporates Haitian Vodou, as it is still marked as evil in interfaith circles. My op-ed went live on Huffington Post on January 11, 2010, and the next afternoon the earthquake struck Haiti. A couple of days later, the Reverend Pat Robertson publicized the infamous evangelical belief that Haiti was being punished for its pact with the devil. Similar views would find space in the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal, the two most widely read papers in the United States.

I began a writing spree that lasted well over two years. The sense that there was so much at stake was a feeling I could clearly articulate, and it was quite evident in my first post-quake op-ed, “Amid the Rubble and Ruin: Our Duty to Haiti Remains,” published January 14 on npr.org. I recounted the impact of my recent trip and the realization that indeed, I could have a relationship with my birth country as an independent adult. What I also found were people with whom I could work in solidarity and who were determined to contribute their collective effort toward transforming the Haiti they had inherited. I say “they” because as a Haitian-American living in the diaspora, I am only too conscious of the fact that I have the privilege of making my life elsewhere. I can always leave, and thus would always be akin to an “outsider within.”6 Only those with concrete knowledge of infrastructural conditions in Haiti truly understood the full devastating impact of that disaster at the time.

In the days, weeks, and months that followed, words, sentences twirled in my head at all hours. I often found myself waking in the middle of the night, driven to writing stints until I got to a point where I felt I had no more to say. Most of the pieces I penned went live. Some (not all of them were about Haiti) were rejected, and others were never submitted,7 a different kind of rejection. It was an opportunity to move away from academic settings as I learned to discern between when and where my opinion could be an intervention of some sort and where it wasn’t worth the effort or would not be effective. Those were the times when I reverted to stubborn professional maxims, unwilling to adapt to generalizations that would appeal to an even broader readership. More often than not, in these instances, my objections concerned matters related to race.

Anthropologist as Public Intellectual

My motivation to tell a different story came from a moral imperative, driven by sentiment and several points of recognition. The first was intellectual awareness that the Haiti in the public domain was a rhetorically and symbolically incarcerated one, trapped in singular narratives and clichés that, unsurprisingly, hardly moved beyond stereotypes. Second, for that reason, it was necessary that such perceptions be challenged. Third, complex ideas about Haiti circulating in the academy stayed among academics, rarely trickling outward. Finally, as a scholar possessing such knowledge, I could add a nuanced perspective to ongoing public discussions about the republic.

The late Haitian anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot, who constantly pondered over whether academics can be, or better yet, can afford not to be public intellectuals, was a great inspiration to me in that regard. In Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (1995), Trouillot made an important point concerning this that is worth revisiting. He warned us not to underestimate the fact that history is produced in overlapping sites outside academia. He wrote: “Most Europeans and North Americans learn their first history lessons through media that have not been subjected to the standards set by peer reviews, university presses or doctoral committees. Long before average citizens read the historians who set the standards of the day for colleagues and students, they access history through celebrations, site and museum visits, movies, national holidays and primary school books.”8 As I learned the broader implications of who gets to tell and write the story, I agonized over issues of social responsibility. What better way to help Haiti than by inserting my anthropological self into some of those overlapping sites to relay critical insights to the general public?

To be sure, these popular areas are particularly ripe for intellectual interventions. This would be nothing new to the discipline. Since the historical development of anthropology, its practitioners have engaged various publics in different ways. This practice can be traced back to the discipline’s “founding fathers”—less bound to academic boundaries—who actively participated in the debates of their time as they sought to explicate social evolution, human nature, and variation.

Later forebears such as Franz Boas, the notable father of American cultural anthropology, had a significant presence as an anti-racist academic who publicly challenged racist ideologies. Melville Herskovits championed the significance of cultural relativism in understanding black people in Africa and the Americas. Ruth Benedict practically redefined conceptual understanding of culture. Margaret Mead, to date, remains an icon as the quintessential example of the public intellectual who not only brought anthropology to the masses through cross-cultural analysis, but did so as host of a television show and through columns in popular magazines.9

While I was taught, in graduate school courses, this history of the influence of public presence on disciplinary traditions, the underlying understanding was that intellectually valuable work, which we were inadvertently encouraged to pursue, was that which produced knowledge for its own sake. Though this belief seemed to be at odds with my agenda (my initial interest was in development), the rigorous emphasis on recognizing how narratives are created, and the pervasive and insidious power of their representations, only made me more curious about their practical implications.

Anthropological queries that challenge the so-called divide between advocacy and analytical work abound.10 There are recurring conversations within the discipline concerning where and how to theoretically locate these “publics,”11 conversations that anthropologists engage in often in overlapping ways.12 Nonetheless, with increasing professionalization and specialization, the presence of anthropologists in the public sphere has changed, in part because academics do eschew this arena.13 In the past, public engagement was more central to the discipline. In recent years, however, the American Anthropological Association has taken to encouraging the public presence of members, to “increase the public understanding of anthropology and promote the use of anthropological knowledge in policy making”14 and its overall relevance in our times.

Still, external causes for the discipline’s obscurity in the public sphere include the fact that in popular imagination anthropology is still equated with a study of the “exotic” rather than everyday social phenomena at home as well as abroad. Moreover, prominent pundits and experts who offer insights on cultural specificities are not only more adept with the media, but their work, as Hugh Gusterson and Catherine Besteman so rightfully note, tends to “cater to their audiences’ existing prejudices rather than those who upend their easy assumptions about the world and challenge them to see a new angle.”15 Undeniably, as we were frequently informed in the op-ed seminar, the likeliness that an opinion piece will influence readers enough to change their perspective is slim, as most minds are set. Therein lies the biggest inhibition to fruitful interventions in the mainstream.

Academe is only so diverse with its set of canons, conventions, and resistances to difference. While much has changed since my days of graduate school, it must be said that the stories of public intellectuals I heard (in nonspecialized courses) generally excluded or marginalized the works of black pioneers in the United States16 who confronted racialized structural barriers that not only severely impeded their work but also determined their professional relationship to the discipline.17 The extensive breadth of their impact is unknown in the mainstream. For example, Zora Neale Hurston and Katherine Dunham both took their training out of the university system, turning to folklore and the arts to make significant contributions across disciplinary boundaries, which to this day continue to highlight expressive dimensions of black experiences. Dunham, using the pseudonym of Kaye Dunn, was actually a public writer who published articles in Esquire and Mademoiselle magazines predating Margaret Mead’s Redbook days. Allison Davis had a tremendous impact outside anthropology, as his studies of intelligence were instrumental in influencing compensatory education programs such as Head Start.18 The pan-Africanist St. Clair Drake, another influential pioneer, introduced, along with sociologist Horace Cayton, the notion of a “black metropolis” to a wide audience,19 before he even finished his doctoral degree.

Back then, black academics and artists deployed their knowledge of anthropology despite conflicted views of it as an esoteric endeavor, as St. Clair Drake put it, with little “relevance” to problems of “racial advancement” in the United States.20 They found it useful in attempts to expose and consider various aspects of black diasporic life in the broader struggle against colonialism and racism. Barred from mainstream mass media, their public interventions were documented mainly in black outlets. They managed to achieve this while differentially positioned vis-à-vis white counterparts who at times actively opposed their presence and activities not only within the discipline, but also inside and outside of universities. Indeed, what was permissible for some was heavily policed by others, including some of these well-known foremothers and forefathers.

In that vein, it must be noted that academia and the media are more congruent than dissonant when it comes to the structural factors influencing the underrepresentation of minorities. It is from this context that I emerged and learned how to maneuver as a black Haitian woman, an anthropologist, bent on issuing a counter-narrative in the public sphere in the post-quake period.

Neither Informant nor Sidekick

I began to write back, in a sense, when it was evident that Haiti was being represented in damaging and restricting ways. Nowhere was this more apparent than in the treatment of Vodou, which was repeatedly portrayed devoid of cultural meaning, and thus reinscribing the “mystical” characteristics ascribed to Haiti and barring it from narratives of modernity. Attempts to demystify this myth had their own challenges. In interviews with white colleagues (usually friends), I was often cast as the “native informant” by the interviewer, while they were seen as “experts.” Together, we not only resisted this impulse but also had to remain vigilant of the aftermath.

The morning after, I would check websites to assure that the text of this new interview actually contained the correct spelling of Vodou instead of “voodoo,” which is used in media style sheets. (The latter spelling reinforces the stereotype and is the popularly recognized term guaranteed to get more hits on search engines.) There were instances in which “allies”21 and advocates in the mainstream and other media would represent Haiti in the most deprecating ways, at worst rendering Haitians invisible and at best, one-dimensional. While awareness of and attempts to address this were excruciatingly exhausting, these misrepresentations were also ripe for critical sociocultural analysis. Enter the native as sidekick.

This is not at all surprising; as I previously stated, the face of public anthropology is predominantly white and male in certain contexts. Although writer Edwidge Danticat and rapper Wyclef Jean were the most prominent Haitians in the media, with his high international profile it was Harvard medical anthropologist and physician Paul Farmer (founder of Partners in Health) who was practically synonymous with Haiti, along with Sean Penn and Bill Clinton.22

Where, if, and how “natives” fit in this visual (economic) order,23 especially in the areas of humanitarian work and post-disaster reconstruction, given their domination by a white-savior-industrial complex, remained unanswered “burning questions,” as Michel-Rolph Trouillot would have dubbed them a decade earlier.

Such moments and insights only reinforced Trouillot’s assertions in Global Transformations: Anthropology and the Modern World (2003) about the status of the native voice in the production of anthropological knowledge. Ethnography was his site of inquiry, while I was surveying the media—in some cases, “leftist” or “alternative” branches of this world. Yet the social hierarchies and other issues were variations on a theme. Like the ethnographer, the journalist serves as mediator; in neither case can the native be a full interlocutor. Moreover, this only reconfirmed the need to address a problem I had been mulling over: “Who is studying you, studying us?”24

I stopped writing about Haiti months later, uncomfortable with speaking on behalf of Haitians, especially given that I had not been there since the quake. Although I had a specific viewpoint to offer on how Haiti and Haitians were being portrayed, I pondered its significance. I made my first trip back the last week of March and stayed through Easter weekend, spending a little time in Port-au-Prince so I could volunteer with a clinic in Petit-Goâve.

I returned feeling desperate. At the same time, I understood that not having hope is not an option for the ones left behind, for those trapped inland, because “nou se mo vivan” (we are the walking dead), as a friend said quite bluntly. Once again, thoughts of social responsibility re-emerged. My public writing entangled with my artistic work in unexpected ways. Invitations to colleges and universities meant audience members gained access to a social scientist, artist, and public commentator simultaneously.

This placed me in a position I have yet to fully decipher. I have at least recognized that with performance, I offer people a visceral point of entry from which critical conversation could develop. This overshadowed audience interest in my artistry, however, as discussions often remained content-driven. Still, the tripartite connection informed my works in multifaceted ways, making me aware of the limits of each, as well as how they complemented each other, and prompted me to reexamine their overall effectiveness in their own rights.

With that in mind and given my initial impulse—responding to a call—I had to negotiate my position within different forms of media. One thing remained indisputable: online publication provides access and extends one’s reach in ways print does not.25 Print, which entails a different process, still has merit, and it is a form of documentation that is more accessible for some, plus it meets a different professional criterion with regard to scholarship, although these writings were not in refereed journals. In any case, I found myself drawn to do more creative projects for my already unconventional career. This was work I was not only determined to do, but could not be kept from. So could it, would it, have any professional value? That remains to be seen, considering recent debates about how to evaluate nontraditional scholarship and university commitments to civic engagement.26

The Making of a Chronicle

The idea to compile these writings into a book came from Claudine Michel, a professor of black studies and education at the University of California–Santa Barbara, and the editor of the Journal of Haitian Studies. In our conversations, she mentioned she was too busy to keep up with my pace, so she had begun to put my pieces into a folder. Then, she insisted I too assemble them as a collection, given the immediacy, frequency, and scope of my purview. She said that as a native daughter anthropologist-performer situated on the margins, I offered a multifaceted insider/outsider perspective on this developing moment in Haitian history, a post-quake chronicle. (I think of it as a memoir of sorts.)

During this time, I had written intermittently, yet consistently, for the Huffington Post, the Ms. magazine blog, the Haitian Times (later HT magazine), and Tikkun Daily; and I was invited to do guest blogs on several niche sites by friends and strangers alike. Each one had its own benefits and challenges. The Huffington Post offered the most freedom as a less mediated space, with little oversight and a vetting process. The Ms. blog provided hard-core fact checking with phenomenal editorial supervision. This was particularly rewarding for the way it influenced me to retain a feminist perspective on issues while being action oriented, keeping the blog’s readership in mind.

The Haitian Times did offer the ultimate audience who possessed background knowledge of never-ending tales of a Haiti continuously maligned in the media. As this readership was more broadly based, the new editor, Manolia Charlotin, began a scholar’s corner to foreground more critically diverse voices on contemporary social and political issues. The Tikkun Daily’s emphasis on repair and transforming the world provided an interfaith community that allowed me to be even bolder where religion is concerned.

While I enjoyed addressing varied and smaller audiences, this compounded the likeliness that I had to keep repeating myself. Still, I enjoyed the practicality of these online blogs that required short-term, albeit intense, focus to respond and deliver. I also valued the fact that I was writing for the present moment.

During that first year, I accepted invitations to submit three different print pieces and proposed a fourth to the journal Meridians: Feminism, Race, Transnationalism—the creation of a small collection of women’s “words” on the earthquake as an archival project. These were particularly challenging, as they took me into diverse directions. The first, “Some Not So Random Thoughts on Words, Art, and Creativity,” was a meditation on several paintings and poems solicited by the curators of an art gallery in Grimma, Germany, for Haiti Art Naïf: Memories of Paradise?, a catalog for an exhibition held in March 2010. I wrote it in tears as I fawned over pictures of the selected paintings. Later, I had to decide whether to allow my writing to be included in the catalog when I strongly disagreed with the curators’ use of the archaic term naïf to describe Haitian art. A mentor encouraged me to stay, noting that more than likely, I would probably be the only Haitian and/or alternative perspective in the catalog.

The second piece was “Why Representations of Haiti Matter Now More Than Ever.” I presented it at the Ronald C. Foreman Lecture at the University of Florida, invited in April 2010 by anthropologist Faye V. Harrison. It turns out the lecture was actually an award that recognized the publicly engaged scholarship of its recipients. The month after, I updated and revised this paper for a special UNESCO plenary on Haiti at the Caribbean Studies Association (CSA) annual conference in Barbados. This panel included sociology professors Alex Dupuy and Carolle Charles, and language and literature professor Marie-José N’Zengou-Tayo, who survived the earthquake. Since I was on sabbatical, I offered to organize this panel for my senior colleagues and compatriots.

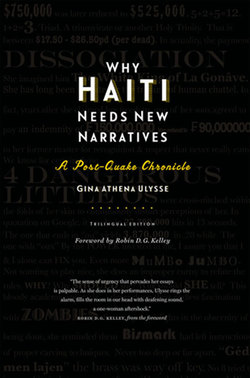

“Why Representations” was first published in NACLA Report on the Americas’ July/August issue, “Fault Lines: Perspectives on Haiti’s Earthquake.” It was among the most academic pieces I had written. At the same time, it was also heavily influenced by my public intellectual training, which encouraged clarity, sharpness, and poignancy. I did not hold back, especially since this piece actually recorded my earliest reactions to television portrayals of the quake and its immediate aftermath. It was reprinted with the title “Why Haiti Needs New Narratives Now More Than Ever” in Tectonic Shifts: Haiti since the Earthquake. This extended volume, edited by Mark Schuller and Pablo Morales, contained an unprecedented number of Haiti-based activists and writers. “Why Haiti Needs New Narratives” became something of a refrain I repeated everywhere I presented my work—hence its use as title of this book.

The third print article was a feature story I wrote for Ms. magazine, “Rising from the Dust of Goudougoudou,” published in early 2011. I went on my second trip to Haiti during the summer of 2010 and conducted research with various women’s groups specifically for this assignment—a rare opportunity for an anthropologist to work with a mainstream print outlet from the inception of a story idea. The Ms. editor encouraged me to include as much history as possible to better unpack and contextualize the complexity of the current situation women faced in post-quake Haiti. For example, ever the ethnographer, I was adamant about revealing class and color dynamics among women’s groups to expose the fallacy in abstractions such as “the poorest nation in the hemisphere.” Moreover, since women were actively engaged in their communities, I got an opportunity to reveal this along with their habit of helping each other.

I grew more and more perturbed as a representative voice for Haitians in Haiti, aghast at the politics and realities of who gets to speak for whom. I have always written and spoken reflexively about issues of position, power, and representation, especially given my diasporic privileges. While I recognize I had access that many in Haiti did not have, I strongly believe that the public still needed to hear from those based in Haiti who can speak for themselves.

The fact is I was also ready to go in another direction to make a different kind of intervention. The “new” space was performance. As my understanding of the media’s role in persistent perceptions of Haiti expanded, my artistic expressions took an even more critical and visceral turn, breaking from linearity and narrative, which were instrumental to the earlier stages of my practice.27 Indeed, I have been engaging in public performances in professional settings consistently since 2001, when I first presented “The Passion in Auto-Ethnography: Homage to Those Who Hollered before Me”28 at an American Anthropological Association annual meeting. My commitment to making creative and expressive works undergirds a dedication to interdisciplinarity—as an embodied intellectual embrace of the hyphen as artist-academic-activist, which is fueled by the contention that no one lives life along disciplinary lines. Hence my determination to use performance to both access and re-create a full subject without leaving the body behind. While I have written about my methods and motivations for doing such work,29 in her 2008 book Outsider Within: Reworking Anthropology in the Global Age, Faye V. Harrison uses aspects of my creative work to make a broader argument for the significance of poetic and performative voices in expanding anthropological dimensions of conceptual, interpretive, and methodological praxis. In Citizenship from Below: Erotic Agency and Caribbean Freedom, Mimi Sheller (2012) has also argued that by challenging narratives of dehumanization, my work exemplifies an anti-representational strategy of resisting and returning the tourist and anthropological gazes.

My Order of Things

This book consists of thirty entries that include blog posts, essays, meditations, and op-eds written and published from 2010 to 2012. These are organized chronologically, and thematically divided into three stages that chronicle my intentions, tone, and the overarching theme of my responses.

The first part, “Responding to the Call,” includes writing done in 2010. This was my most prolific year, during which I did more macro-level analysis, paying particular attention to structural matters that have been historically rendered abstract in a mainstream media. My interest and focus on politics was a retort to the potential, however brief, that this moment represented.

The second part, “Reassessing the Response,” begins in January 2011, recognizing the first year marker of the quake. I participated in a march that was held in New York City and wrote about diasporic anxieties around this “anniversary” on pbs.org. Since writers hardly ever choose their own headlines, the piece, which I entitled “Haiti’s Fight for Humanity in the Media,” was published as “The Story about Haiti You Won’t Read.” By this time, both the scope and manner of my discursive and expressive ripostes were changing. Indeed, those of us with nuanced historical knowledge of both local and geopolitics already understood that no matter how well-meaning international efforts and developments, these were performances of progress that would ultimately uphold the status quo.

I consciously took an explicit feminist turn. I wrote more about women’s concerns and those who were breaking ground in their own ways, in part to counter my disillusionment with international and national developments. The majority of the pieces in that second phase were published on the Ms. blog. I also edited “Women’s Words on January 12th,” a special collection of essays, poems, photographs, and fiction for Meridians.

The final part, “A Spiritual Imperative,” is the shortest one. I barely wrote in 2012, having taken on another Haiti-related professional task30 that severely limited my time. By then, I had turned from political matters to focus mainly on creativity and art. I was committed to drawing attention to the religious cleansing, or the bastardization of Vodou that was now in full effect. I characterize this shift as an ancestral imperative, as it was driven by a familial move away from our spiritual legacies and responsibilities.

So the last piece, “Loving Haiti beyond the Mystique,” appeared in the Haitian Times (HT) to mark the 209th anniversary of the Haitian Revolution, January 1, 2013. It is actually an excerpt from Loving Haiti, Loving Vodou: A Book of Rememories, Recipes and Rants, a memoir written in 2006. I submitted “Loving Haiti beyond the Mystique” at the request of the editor unnerved by the irony of its relevance seven years later.

Nota Bene: Illuminating Errors

The pieces in this collection are reprinted here lightly edited, as they were originally published with the hyperlinks removed. They also contain errors (including a tendency to refer to the republic as an island) for which I alone am responsible. I came to recognize it for what it is: a subliminal signification constantly made by default.

Additionally, the more diverse my venues, the more I repeated myself. These discursive reiterations, I must admit, are also, in part, a strategic device at play. Indeed, my writing has always entailed a performative component—a purposeful orality if you will, since I actually read pieces out loud as I wrote them. Mea culpa, dear reader, as annoying as they may be to read here, compounding them is necessary to reinforce certain points that I believe are crucial to illuminating Haiti’s past and path.

NOTES

1 The ideas and extensive writings of the late cultural theorist Stuart Hall had a profound impact on my work and thinking. He insisted on the routes of diasporic experiences as opposed to the more essentializing notion of roots, which I explore in detail throughout this introduction. When I was a graduate student, I attended a seminar at the University of Michigan in 1999 where Hall stressed this point: “Instead of asking what are people’s roots, we ought to think about what are their routes, the different points by which they have come to be now; they are, in a sense, the sum of those differences.” Journal of International Institute 7, no. 1 (Fall 1999). Another primary influence on me has been anthropologist Ruth Behar, my dissertation adviser, who not only has used the personal to write culture and to cross borders in her own way within and outside the academy, but whose intellectual and artistic preoccupations with concepts of home entail meditative interrogations of her identity as a Jewish Cuban negotiating her complex diasporas. Besides her ethnographies and memoir, she has written essays, poetry, and used photography and film to better nuance answers to her questions. Her works include The Vulnerable Observer (1996) and An Island Called Home (2007).

2 In a 1998 New York Times article by Garry Pierre-Pierre, Danticat was quoted recognizing the impact of the hip-hop star’s Haitian pride, which he professed whenever and wherever he could. She said, “When we think of Haitian identity, it will always be before Wyclef and after Wyclef.’’ Prior to his presence on the popular scene, stigmatized Haitians (youths especially) often hid their national identity to protect themselves from bullying and other negative responses.

3 I should note that this, of course, is with my full understanding of the complex impact of one’s formative years on development as a social being.

4 Up until 2003, the country used to be divided into nine geographic and political departments. With over one million Haitians living in the United States, Canada, the Dominican Republic, France, and other countries in the Caribbean and elsewhere, the tenth department emerged as an informal category in the early 1990s that has since become more established in as far as Haitians abroad continue to seek political representation, demanding the Haitian Constitution be amended to allow dual citizenship.

5 For the director of the Center for Public Anthropology Robert Borofsky, public anthropology “demonstrates the ability of anthropology and anthropologists to effectively address problems beyond the discipline—illuminating larger social issues of our times as well as encouraging broad, public conversations about them with the explicit goal of fostering social change.” From “Conceptualizing Public Anthropology,” 2004, electronic document accessed July 13, 2013. As I discuss later, this is a contested term among practitioners both inside and outside academe.

6 I have yet to decode the complexity of this position as a Haitian-American among Haitians at home, as a Haitian among blacks in the United States, and/or as an other among white anthropologists, which I have discussed at greater length in my first book, Downtown Ladies, an ethnography of female international traders in Kingston, Jamaica. To make sense of this location, I draw upon Faye V. Harrison’s work on peripheralized scholars engaged in the decolonizing anthropology project. As Harrison so rightfully notes in accord with sociologist Patricia Hill Collins, who deploys this term, “‘outsiders within’ travel across boundaries of race, class, and gender to ‘move into and through’ various outsider locations. These spaces link communities of differential power and are commonly fertile grounds for the formulation of oppositional knowledge and critical social theory”: Faye V. Harrison, Outsiders Within: Reworking Anthropology in the Global Age (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2008), 17.

7 I wrote numerous other pieces about bell hooks, Audre Lorde, President Obama, Oprah, art, feminism, performance, and other topics that went live, as well as others I wrote just for the sake of practice.

8 Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Haiti’s Nightmare and the Lessons of History: Haiti’s Dangerous Crossroads, ed. Deidre McFayden (Boston: South End Press, 1995), 20.

9 For more on Mead see Nancy Luktehaus, Margaret Mead: The Making of an American Icon (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010).

10 Building on the work of Charles Hale (2006), Michal Osterweil has argued that the notion of “activist research” and “social critique” as disparate is a falsified one since knowledge is a crucial political terrain, and both these approaches actually “emerged as responses to the increasing recognition of anthropology’s role in maintaining systems of oppression and colonization that were unintentionally harming the marginalized communities anthropologist were working with.” See Michael Osterweil, “Rethinking Public Anthropology through Epistemic Politics and Theoretical Practice,” Cultural Anthropology 28, no. 4 (2013): 598–620, and Charles Hale, “Activist Research v. Cultural Critique: Indigenous Land Rights and the Contradictions of the Politically Engaged Anthropology,” Cultural Anthropology 21, no. 1 (2006): 96–120.

11 A big issue is what exactly distinguishes applied, practicing, and public anthropology from each other. Applied anthropology has its origins in (international) development work and is policy driven. Practicing anthropology, on the other hand, often emphasizes collaborative work with communities, also with the aim of using the work to affect public policy. Public anthropology is also action driven, with the aim of transforming societies. While definitions of these approaches vary and depend on the schools of thought from which they stemmed, as Louise Lamphere (2004) has rightfully argued, in the last two decades these approaches have been converging as collaboration, outreach, and policy are becoming more common in certain graduate programs.

12 Setha Low and Sally Merry mapped out the following ways that anthropologists can be more engaging: “(1) locating anthropology at the center of the public policy-making process, (2) connecting the academic part of the discipline with the wider world of social problems, (3) bringing anthropological knowledge to the media’s attention, (4) becoming activists concerned with witnessing violence and social change, (5) sharing knowledge production and power with community members, (6) providing empirical approaches to social assessment and ethical practice, and (7) linking anthropological theory and practice to create new solutions.” See Low and Merry, “Engaged Anthropology: Diversity and Dilemmas,” Current Anthropology 51, no. S2 (2010).

13 Academics in general, including anthropologists, who engage with the public sphere are still stigmatized and are not taken as seriously by some peers. At the same time, anthropologists, especially in the United States, are concerned that, in the media, matters regarding human conditions tend to be discussed by non-specialists. For more on this issue, see Catherine Besteman and Hugh Gusterson, Why America’s Top Pundits Are Wrong: Anthropologists Talk Back (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), and Thomas Hyllan Eriksen, Engaging Anthropology: The Case for a Public Presence (Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic, 2006).

14 American Anthropological Association website, AAAnet.org.

15 Besteman and Gusterson, Why America’s Top Pundits, 3.

16 See Ira E. Harrison and Faye V. Harrison, eds., African-American Pioneers in Anthropology (Urbana: University of Illinois, 1999).

17 Indeed, my work stems from a much bigger lineage that includes Haiti’s own tradition of ethnology, which dates back to the work of nineteenth-century anthropologist and politician Anténor Firmin. The Bureau d’Ethnologie in Port-au-Prince founded by Jean Price-Mars incorporated works that not only blurred the lines between ethnology and the literary but also stemmed from a radical activist perspective against U.S. occupation and other forms of imperialism. The particularities of my training, though steeped in North American traditions, did include area studies that incorporated and recognized the impact of the Haitian school.

18 See Faye V. Harrison, “The Du Boisian Legacy in Anthropology,” Critique of Anthropology 12, no. 3 (1992): 239–60.

19 Drake and Cayton’s Black Metropolis: The Study of Negro Life in a Northern City was first published by Harper & Row in 1945 and was reprinted twice, in 1962 and 1970, with updates commissioned by the original publishers. The first printing included an introduction by the popular novelist Richard Wright.

20 St. Claire Drake, “Reflections on Anthropology and the Black Experience,” Anthropology & Education Quarterly 9, no. 2 (1978).

21 For a critique of the problems of “allyship” see Aileen McGrory, “Queer Killjoys: Individuality, Niceness and the Failure of Current Ally Culture” (Honors thesis, Department of Anthropology, Wesleyan University, 2014).

22 Prior to the quake Farmer joined the office of the UN envoy that was headed by Bill Clinton. There was a strange irony in this trio of white American men—Farmer, Clinton, and Penn—as the “saviors” of Haiti, which at times prompted me to refer to them as “the three kings.”

23 This question is answered in part by Raoul Peck’s documentary Fatal Assistance (2013), a two-year journey inside the challenging, contradictory, and colossal post-quake rebuilding efforts that reveals the undermining of the country’s sovereignty and concomitant failure of relief groups, international aid, and nongovernment organizations (NGOs) with ideas of reconstruction that clashed with actual Haitian need. It also offers insights on where did the money (not) go.

24 I raised this question during a plenary session at the twenty-first annual Haitian Studies Association conference in 2009. I also explored this issue in some detail in the 2011 Ms. blog piece “Why Context Matters: Journalists and Haiti,” which is included in this collection. I develop these ideas even further in my book-in-progress, “On What (Not) to Tell: Reflexive Feminists Experiments.”

25 Swedish anthropologist and former journalist Staffan Löfving considers the issues of temporality in these two fields. He notes that “writing slowly about fast changes constitute[s] a paradox in anthropology. The paradox in journalism consists of writing quickly and sometimes simplistically about complex changes.” Quoted in Eriksen, Engaging Anthropology, 110.

26 In the inaugural Public Anthropology review section of the American Anthropologist, Cheryl Rodriguez noted “the ways in which anthropologists are using cyberspace to create awareness of women’s lives in Haiti. Primarily focusing on the use of websites and the blogosphere as public anthropology, the review examines the scholarly and activist implications of these forms of communication”: see Rodriguez, “Review of the Works of Mark Schuller and Gina Ulysse: Collaborations with Haitian Feminists,” American Anthropologist 112, no. 4 (210): 639.

27 There was something brutal and disconcerting about the even greater presence of foreigners with means and power on Haitian soil, an “humanitarian occupation,” as these have been called by Gregory H. Fox (2008), or a neo-coloniality in the post-quake moment that intuitively brought me back to seeking solace in the work of Aimé Césaire, especially Cahier d’un retour au pays natal / Notebook of a return to the native land, and Discourse on Colonialism. Both of these texts had profound influence on my thinking as an undergraduate student and were instrumental in my decision to study anthropology to be of help to Haiti. I became more familiar with Suzanne Césaire’s work, The Great Camouflage: Writings of Dissent (1941–1945), which inspired me to finally embrace my secret attraction to surrealism as I gained a deep appreciation for her lyrical rage. These works made me even more open to the possibilities of performance as an ever-expansive space to express raw emotions. Lastly, I should add that there is another complex point, concerning the appeal of these Martinican writers to me as a Haitian, which I believe is necessary to note but won’t discuss any further.

28 See Gina Athena Ulysse, “Homage to Those Who Hollered before Me,” Meridians: Feminism, Race, Transnationalism 3, no. 2 (2003).

29 See chapter 21, “When I Wail for Haiti: Debriefing (Performing) a Black Atlantic Nightmare.” An extended version of this essay, titled “It All Started with a Black Woman: Reflections on Writing/Performing Rage,” will be published in the black feminist anthology Are All the Women Still White?, edited by Janell Hobson (New York: SUNY Press, forthcoming).

30 I was asked to serve as the program chair for the Caribbean Studies Association annual conference under the leadership of Baruch College sociologist Carolle Charles, who became the first Haitian president elected in the association’s thirty-seven-year history. My role was to organize a five-day international conference in Pointe-à-Pitre, Guadeloupe, that would eventually consist of over 150 panels and more than six hundred participants. I knew that to focus, there would be no time to commit to writing.