Читать книгу Indigenous Toronto - Группа авторов - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

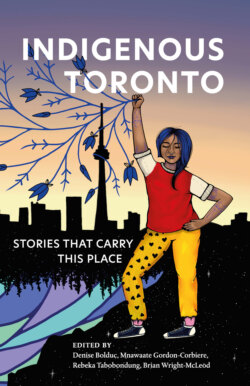

A STORY ABOUT THE TORONTO PURCHASE

ОглавлениеMARGARET SAULT

Even though this event occurred over two centuries ago, in 1787, it still inspires fascination, as there are so many documents, letters, and reports on what happened.

When the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation negotiating team met with representatives from the Justice Department in 1996, the head lawyer made a comment that remains in my mind. ‘I cannot believe there is so much written on this subject,’ he said, referring to the Toronto Purchase. The records and documentation are so abundant, and all that was needed was to find them. So this is a story about the Toronto Purchase.

Let’s start in 1787. The Crown felt it needed a secure military communication route from Lake Ontario to Lake Huron that did not utilize the current one, along the lakefront. They wanted a route that would take them out of harm’s way. The colonialists explored some routes and determined they had to make purchases with the Mississaugas and the Chippewas.

Sir John Johnson, then the head of the Indian Department, called a meeting of the Mississaugas and other First Nations to distribute ‘annual presents’ for the military alliance during the American Revolution. At the time of this gathering, Johnson talked to the Mississaugas about land he wanted to purchase from them, along the north shore of Lake Ontario, as well as the ‘carrying place’ from Toronto to Lake Simcoe. This was the route the British wanted to be safe from their enemies.

What actually transpired is that Johnson thought the British had a treaty with the Mississaugas for the passage and the land known as the Toronto Purchase. As it turned out, discussions leading to a potential treaty, and the annual presents given, settled on the amount that was said to be paid to the Mississaugas of the Credit for the land.

Life went on, and the Crown thought it had secured the land. Some years later, a law clerk was going through the files and came upon the so-called treaty, finding instead a blank deed with no land description, but with the marks, probably dodems of three Mississaugas chiefs, wafered onto the document.

However, the Crown was already selling the land and building the capital there. When the law clerk made the higher-ups aware of the situation, their initial response was to withhold from the Mississaugas that there was no treaty. The correspondence went back and forth, and the Crown decided it would be best to tell the Mississaugas in order to avoid an uprising if they were to find out later on. This was a very delicate time, as one of the Credit River chiefs, Wabakinine, along with his wife, were murdered by the Queen’s Rangers. The Credit Indians wanted to retaliate, but Joseph Brant talked them out of it.

In 1798, Johnson, when asked what lands he purchased from the Mississaugas in 1787, wrote: ‘I think it was a ten-mile square at Toronto, with two to four miles on each side of the carrying place to Lake Simcoe, where the same ten-mile square was at the end of the trail.’ It is strange that Johnson’s recollection of the land was only for the ten-mile square with two to four miles on each side of the ‘carrying place’ up to Lake Simcoe. In its wisdom, the Crown decided to treaty again with the Mississaugas for the lands. They had no choice – without a treaty, they did not own the lands they were already using, selling, and building as the Town of York.

The boundaries of the purchase were the next difficult issue. In 1788, Alexander Aitkin, Upper Canada’s surveyor general, was given instructions to survey the lands purchased from the Mississaugas. He encountered some tense moments when he was surveying the eastern boundary to the end of Ashbridge’s Bay. The Mississaugas of the Credit said they had only given lands to the Don River in the original treaty. The same problem occurred at the western boundary, where the Mississaugas protested the boundaries, saying the agreement extended only to the Humber River, and not to the Etobicoke River.

The discontent was so severe that Aitkin feared for his life. The Butler’s Rangers were brought in to watch that nothing happened, and Aitkin went ahead and surveyed west to the Etobicoke River. He had only surveyed about three miles when the Rangers left. He stopped his work and left, too, as he did not want to encounter the wrath of the Mississaugas again.

With all the discrepancies over the boundaries, only a partial survey was completed. With an incomplete survey and no description of the land, what would be the next step? The Crown believed a second treaty had to be negotiated with the Mississaugas, and in 1805, the next negotiation took place. But there were more problems around resolving the land issue.

Signatures of parties ratifying the Toronto Purchase (1805).

Johnson wanted a ten-mile square with two to four miles on each side of the carrying place. But the Mississauga chiefs who had been at the 1787 meeting and the 1788 survey attempt were now dead. The Crown had waited until 1805, as another large land surrender was being considered to the west of the Toronto Purchase, known as the Mississauga Tract, extending west to the Brant Tract. The Crown needed to get the land survey straightened out so it could proceed with the Mississauga Tract treaty.

In preparation for a meeting with the Mississaugas, the Crown created four maps: two of the Mississauga Tract and two of the 1787 Toronto Purchase. Something we did not find in our research was any evidence showing how the Crown determined the northern boundary of the Toronto Purchase. One map shows the western frontage to Ashbridge’s Bay and the eastern frontage to the Etobicoke River, while the other details the boundaries of what the Mississaugas told Aitkin in 1788 – east only to the Don River and west no further than the Humber River, and not including the Toronto Islands. The two versions of the Mississauga tracts would extend either from the Etobicoke River or the Humber River. The Crown’s only interest was to secure title to the capital, York, as well as to the rest of the Mississaugas’ land along Lake Ontario.

When the meeting took place, on July 31, between William Claus, the Crown’s Indian Department agent, and the Mississaugas, Claus asked the Chiefs what the boundaries of the 1787 treaty were. Chief Quinepenon stated: ‘[A]ll the Chiefs who sold the land are dead and gone. We cannot absolutely tell what our old people did before us, except by what we see on the plan and what we remember ourselves and have been told.’

Claus only showed the Mississaugas the map with the broader boundaries, from Ashbridge’s Bay to the Etobicoke River, with the northern boundary being twenty-eight miles inland and fourteen miles across. The total area spanned 250,880 acres (101,527 hectares).

In other words, the so-called 1805 treaty went far beyond the acreage of the ten-by-ten-mile square that Sir John Johnson had talked about in 1787.