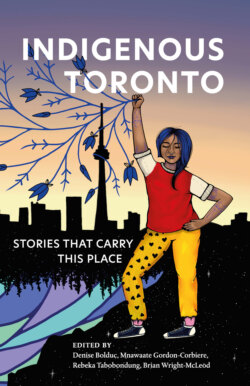

Читать книгу Indigenous Toronto - Группа авторов - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеRISING LIKE A CLOUD: NEW HISTORIES OF ‘OLD’ TORONTO

HAYDEN KING

Every year for the past few, my family and some close friends have travelled a few hours east of Toronto to Presqu’ile Provincial Park. Amid the Explorer RVs, CanRock from competing portable speakers, and smog from dozens of campsites burning green wood, we listen to the waves of Lake Ontario and watch our kids run and laugh and grow together.

The first of these trips included a visit to the lighthouse at Presqu’ile, where we also found a small historical archive of the peninsula, which is famous for its treacherous waters and shipwrecks. There is a plaque here, too, recognizing the HMS Speedy, lost in a snowstorm in 1804. The ship was transporting the accused Anishinaabe murderer Ogetonicut and his prosecutors from York (Toronto) to Newcastle (Brighton).

This incident was a devastating blow to a young colony, as members of York’s ruling class (a justice and lawyers, a royal surveyor, the first solicitor-general of Upper Canada), plus six handwritten constitutions of Upper Canada, were lost.

I’ve since spent a lot of time thinking about this plaque, sitting with the uneasy reality of colonial expansion into our territories, to places like Presqu’ile and beyond. Toronto is unique in that sense. It is the heart of empire in Anishinaabe Aki, source of the flood of colonialism that moved through time and across space, bringing a physical infrastructure with it, but also a narrative of radiating ‘progress.’ What we find in historical plaques and texts is a Toronto – and a Canada – void of Indigenous people, except as criminals or ghosts, doomed like Ogetonicut in the darkness.

But what if Ogetonicut had lived, swimming to the familiar shore his captors could not see?

A BRIEF HISTORY OF TORONTO HISTORIES

In the basement of my mother-in-law’s Mississauga home is a small archive. Carol would not call herself a historian, but she understands more about Toronto’s history than anyone else I know. When I was asked to write a chapter for this book, my first thought was of that archive: dozens of books on the history of Toronto that I had been keen for so long to crack and hate-read. Over a few weeks in the late summer of 2020, I did just that, sharing frustration with my sympathetic Torontophile mother-in-law.

I got familiar with Henry Scadding and John Ross Robertson, Edith Grace Firth and Eric Arthur, Mike Filey and Allan Levine – the noted Toronto historians across the eras, among many others. Despite works spanning 150 years, remarkably similar themes reoccurred in their telling of Toronto’s early history. I am most interested in these early years, the genesis of Toronto, because that story frames all that follows. And, by and large, it is the only era of Toronto’s history where Indigenous people appear.

The story proceeds along these lines: 1) there were probably some Indians in the Toronto area at one time, but with limited presence; 2) the actual discovery of Toronto was by Étienne Brûlé, aided by some Indians, and ostensibly on behalf of the French during their limited possession; 3) finally, the Englishman John Graves Simcoe arrived with his wife and son to carve Toronto out of the lakeshore as the Indians watched.

Between the lines, the corresponding themes revolve around the land being ‘empty’ and free for the taking; if any Indigenous people were here, they were of little consequence; and the Indians were childlike in the shadow of greatness. Taken together, this narrative serves a purpose: obscuring Indigenous presence, agency, language, and, perhaps most importantly, a contemporary existence (which reinforces all that comes before) to justify a settler colonial Toronto. This is the cycle and nature of erasure.

‘OLD TORONTO’

The grandfathers of Toronto historians are undoubtedly Henry Scadding and John Ross Robertson. Both call their reflections on early history ‘Old Toronto,’ as if the ‘pre’-Toronto history is somehow still possessed by the city. Interestingly, works by both men have been reproduced and/or edited into distilled volumes repeatedly, with mentions of Indigenous people or communities largely removed. Perhaps this editing was for the sake of more sensitive modern readers who might take offence at the language of ‘savages.’

That being said, later writers differed little in their treatment of Indigeneity. In 1971, G. P. deT. Glazebrook wrote that the story of Toronto is the story of a ‘town dropped by the hand of government into the midst of a virgin forest. For the site chosen no record exists of earlier habitation although small groups of Indians may have at one time lived not far from it.’ Meanwhile, YA author Claire Mackay in 1991 wrote that ‘this is the story of a city and how it grew: from an unknown and unpeopled place …’

Journalist Allan Levine’s 2001 take is slightly more sympathetic, if general and with an enduring ethnocentrism. ‘[T]he Great Lakes region was home to nomadic hunters whose lives were governed by the seasons and supply of animals,’ he wrote. ‘Though these hunting and gathering societies were primitive, they had developed their own traditions, culture, and spiritual beliefs …’

This theme of terra nullius – where Indigenous people may have called what became Toronto home, but only during the Stone Age – is expanded as the history goes on.

BRÛLÉ’S BABY

The hero of ‘Old Toronto’ in the consensus history of Toronto is Étienne Brûlé.

Evidence for that heroism is bolstered by stereotypes. Levine explains that as ‘Brûlé continued his explorations … he was captured by the Seneca. They tortured him, a sign of respect from the Iroquois’ point of view. He managed to win his release by convincing them that a thunderstorm was a symbol of a higher power watching over him; or perhaps the Senecas hoped that he would help them make peace with the French …’

Levine doesn’t cite his source for this childlike gullibility of the Seneca, nor their supposed respect for Brûlé. Nonetheless, the fable infantilizes the Seneca so they can be instrumentalized to venerate Brûlé.

Levine is not alone in this. Architect Eric Arthur is perhaps the most romantic of the Toronto historians. ‘We can stand where Étienne Brûlé stood on a September morning in 1615,’ he wrote in Toronto: No Mean City. ‘To the south he would look on the great lake, its waves sparkling in the autumn sunshine, its farther shore remote and invisible. To that lonely traveller, the first of his race to set eyes on Lake Ontario, the sight must have been no less awe-inspiring than that which, under poetic license, Cortez saw from his peak …’

The link to Cortez here is an obvious celebration and ode to the rightness of colonization. But this is all permissible because Arthur also peddled the empty-land narrative. After sparing one whole paragraph for the lives and humanity of those non-white people, nomadic fishermen and women, another paragraph is spent on the conflicts that ‘emptied’ Southern Ontario, allowing for the guilt-free exploration by Brûlé and later settlement by Simcoe, et al.

But alas, poor Brûlé, ‘after some years among the Indians of Toronto, was murdered and likely eaten by them,’ speculated the politician-pundit William Kilbourn in 1984.

SIMCOE STREET

John Graves Simcoe was a Cortez-like figure himself. The man was responsible for claiming land and erasing dozens – maybe hundreds – of Indigenous place names in much of the Toronto region and replacing them with the names of English men, many of which persist to this day. Notably, Simcoe’s renaming of Toronto as ‘York’ was one that didn’t stick.

Even without the embellishment of historians, Simcoe was a deeply colonial figure: he sailed on a schooner named the Mississauga1 and slept in Captain James Cook’s tent, E. C. Kyte notes in the 1954 edited version of Robertson’s Landmarks. How it was retrieved after Cook’s death while attempting to invade Kanaka Maoli territory, I do not know.

But like Brûlé, Simcoe gets the ‘founder’ treatment. The narrative of the ceremonial naming of the city is so similar in the Toronto history canon that multiple distinct authors appear virtually indistinguishable:

‘When John Graves Simcoe landed on the marshy shore of Toronto Harbour in 1763, there were only a few just-finished huts marking the rude beginnings of the new capital of Upper Canada’ (Bailey, 1984). But ‘amid the beat of drums and crash of falling trees’ (Innes, 2007) and ‘in front of a small audience that included Mrs. Simcoe, ready as ever to support her husband (and) their young son Francis held in the arms of an old Indian delighted with the loud noise (Glazebrook, 1971), ‘Simcoe christened his town site York. This was after the Duke of York, later Commander in Chief of the Army’ (Firth, 1962).

In this version of the story, the ‘old Indian’ is to Simcoe what the Seneca were to Brûlé: passive elements of the scenery, their silence implying a sanction of ‘civilization.’

RETURN OF THE RISING CLOUD

An accurate spelling of ‘Ogetonicut’ is Okaanakwad. The translation is ‘Rising Cloud’ or ‘Rising Cloud Man.’ It is unclear if colonial recordkeepers knew the pronunciation and translation of Okaanakwad or if they cared. Considering that he was simply a prop in the colonial story of Toronto, like so many others, it is not surprising that his life was treated with disrespect.

After all, he was merely a criminal, though one whom the ‘progressive’ historians at least acknowledge was avenging a wrong: the murder of his kin by a white trader, John Sharp. Colonial officials had promised Okaanakwad – in the presence of Pontiac, among others – that the trader would be prosecuted. But when delays made prosecution unlikely, Okaanakwad sought out Sharpe himself, according to legal historian Brendan O’Brien in his 1992 account of the case. Soon after the confrontation, Okaanakwad was arrested in Toronto, charged, and bound in the hull of the Speedy to face trial in Newcastle.

As books on the history of Toronto move out of the early ‘discovery’ years and toward settlement, the mentions of Indigenous people thin. Exceptions are cases like these, where Indigenous people are noted as criminals who must be brought to heel. This is actually common in colonial settings. Australian historian Lisa Ford, in her 2010 study Settler Sovereignty, argued that colonial authority in New South Wales (Australia) and Georgia (United States) became formalized by criminalizing Indigenous people and installing ‘law and order’ in the colonies. It appears that was the case in Toronto, too, and it is reflected in historical narratives.

In that sense, the Toronto historians are complicit. The harms of colonization occur in many registers but include discourses of disappearance and the rightness of foreign rule at the expense of Indigenous life, repeated and reprinted in volumes of self-serving text. While alternative histories are emerging in the work of Victoria Freeman and Jennifer Bonnell, among others, it has to be acknowledged that the histories of Toronto are typically histories (and historians) of violence.

We endure nonetheless. This book is a reflection of that endurance and a helpful corrective to settler fantasies. It tells a more balanced account of Anishinaabe, Haudenosaunee, and Wendat communities, then and now. It offers the space for us to reclaim our ancestors’ language and legacy, rewriting ourselves back into a landscape from which non-Indigenous historians have worked hard to erase us.

But we are there in the skyline and throughout the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), along the coast and in all directions. I’ll be back at Presqu’ile again soon, too, sitting with friends and trying to calm our wild children so we can share a new story of Okaanakwad, one about how we swam to shore.

(Thanks are owed to Carol Hepburn, Susan Blight, Angie King, Jeff Monague, and Vanessa Watts for their support, advice, and insight on this chapter.)

A NOTE ON SPELLING

Regarding terms or phrases in Anishinaabemowin, Kanien’kehá:ka, or any other Indigenous language that appears in these pages, there may be variations in spelling and grammar. This diversity is common among Indigenous authors and attributable to regional dialects or simply the result of translating orality to text. While there are standardized writing systems for most Indigenous languages, the editors have chosen to defer to the authors’ preferred spelling and grammar.