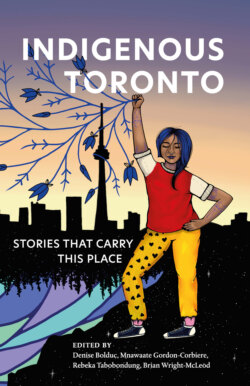

Читать книгу Indigenous Toronto - Группа авторов - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ACTIVITY

ОглавлениеDraw a rough outline of Lake Ontario in the centre of the page.

Start from as far back in time as you can imagine, origin stories welcome.

Plot the ‘Ancestral Homelands’ of the Neutral, the Wendat, the Seneca, Haudenosaunee, Mississaugas of the Credit, Anishnawbe, and any other nations you may be aware of having called this territory home.

Use the internet to research archaeological settlement sites, shifts of populations around Toronto, and forced relocations of each Nation. Plot the current locations of each Nation. Use symbols and gestural drawing to get across the spirit of the movement.

Add diamond shapes to indicate places of council and meeting.

Copy it on a fresh page without Lake Ontario present, zooming in or out to fit the shape to the page. Look at the resulting network as though it were an abstract artwork. Title it.

TKARONTO

Toronto/Tkaronto/Aterón:to/Tsi Tkarón:to roughly translates from Mohawk to over there is the place of the submerged tree or trees in the water. The word has been variously translated to abundance or a place of plenty in Wendat, then attributed to mean the meeting place. A French cartographer in 1680 wrote, Lac Taronto at Lake Simcoe, north of the city. Mnjikaning, the place of the fish fence, refers to the narrows between Lake Simcoe and Lake Couchiching, where remnants of a 4,500-year-old weir still stand. Other early French maps show variations of Toronto written along a few rivers leading through the current city into Lake Ontario, clearly indicating the frequency of weir fishing in and around the city, a factor in the founding of the French and English trade forts in the region. Hundreds of fishing camps have been located along flats of Toronto’s rivers.

The name of the city has been highly disputed. For a long time, it was believed to mean abundance or a place of plenty in Wendat, then attributed to mean the meeting place. Every nation that lived here knew about the weirs. This would have been a place where the rules of the Dish with One Spoon would have applied, I imagine. The French took note of these places to hang nets and spear fish with ease.

I learn a lot about Indigenous Toronto through social media. Layers of contemporary voices have contributed to a more rounded understanding of the city’s name and all the political complexity it carries. I picked up the Mohawk word Tsi Tkarón:to, ‘over there is the place of the submerged tree,’ from a social media post. The Seneca villages were right along the lakefront, and many of the old Wendat sites are upriver, north of Davenport Road, so ‘over there’ would make sense. This also indicated the presence of Mohawk people at the predominantly Seneca sites. It is clear to me that I will never fully grasp these descriptors without investing in my language.

When I started the research phase for Talking Treaties in 2015, I thought I’d be able to draw a clear picture for myself around the Indigenous agreement-making narratives in the city. Years later, I’m still digging my way through documents and oral narratives with more questions than answers. How much original source material must I carry with me? I know these written documents cannot be trusted alone. I worry about getting stuck on mistranslations. I can only get answers by having language speakers, knowledge keepers, anthropologists, and geo-mythologists all in one room. What essential understandings do I need first, before picking up these words? Can the Eurocentric scribe’s choices ever represent the Indigenous spirit of intent? How can anyone be so confident in their assertions of text over context? What am I doing with all this information?

AND SO BE ONE

In 1700, the Haudenosaunee were at a trade meeting in Albany, New York, where they let the English know of the Anishinaabe call for peace, and to be united under the Dish with One Spoon.

We have come to acquaint you that we are settled on Ye North side of Cadarachqui Lake near Tchojachiage [Teiaiagon] where we plant a tree of peace and open a path for all people, quite to Corlaer’s house [Schenectady], and desire to be united in Ye Covenant Chain, our hunting places to be one, and to boil in one kettle, eat out of one spoon, and so be one; and because the path to Corlaer’s house may be open and clear, doe give a drest elke skin to cover Ye path to walke upon.

The Haudenosaunee answered:

We are glad to see you in our country, and do accept of you to be our friends and allies, and do give you a Belt of Wampum as a token thereof, that there may be a perpetual peace and friendship between us and our young Indians to hunt together in all love and amity.2

I spoke at an action blocking the train tracks for #ShutDownCanada in February 2020. I never speak publicly at those actions, but I went ahead and talked about the application of the teaching in the Dish with One Spoon to our personal relationship to resource extraction. The agreement is a gesture of regional genius born of the fact that this is a very rich territory. Everyone has the right to eat and sustain their lives, but there are some rules. I wondered, aloud, if it was too far-flung to apply the teachings of the Dish to the role and duty of the federal government in relation to environmental policy. The Eurocentric preoccupation with individual choice would be overridden by the dictates of the land.

GREAT PEACE

In 1701, the kettle was shared at the Great Peace of Montreal, orchestrated by the French. Thirty-six Indigenous nations sent representatives to negotiate a halt in fighting, including the Mississaugas. The beaver supplies had dramatically decreased due to overhunting and tensions between nations would often result in disputes in the common hunting grounds. Together, these nations confirmed an agreement: they would not kill each other if they met in common space.

At this meeting, the Mississaugas of the Toronto area were represented by Onanguice, Chief of the Potawatomi. He asked the Haudenosaunee to eat from the same kettle when they met on the hunt. Their relationship, now, when in common space, would be of trust and equality; they would look to each other as relatives. They had a shared common interest, that of the security and preservation of their way of life. The French presented a large dish of meat to the gathered chiefs. At this meeting, no specific territory was defined or rules laid out, but a common understanding was reached to share use of the hunting grounds.

And what of the French legacy of alliance with regional Indigenous Nations? Addressing the French king as Father implied a duty to protect and provide. As the English moved into the old French forts in Toronto, they also took up the task of continuing to provide gifts to Indigenous partners. With the Treaty of Paris, forged so far from Toronto, the King of England assumed the role of the dad, soon providing new rules for land cessions and trade.

The ideas in the Dish with One Spoon have been held up to bring us together in the face of European thought dominance. Odawa Chief Pontiac activated the Dish to unite Indigenous Nations against the incursion of English rules around the time of the Royal Proclamation in 1763. Seeking to solidify Indigenous alliances, English representative Sir William Johnson must have been aware of the Dish as he designed the symbolism used in 1764’s Treaty of Niagara, the wampum-based translation of the Royal Proclamation delivered from the English.

Although it’s unclear if Johnson’s Mohawk partner, clan mother Molly Brant, was involved in devising the acts of political theatre that made Niagara successful, the speeches and embodied acts of alliance-making were drenched in Indigenous metaphorical language. Was the shared vision of the Dish used to strengthen the words delivered at Niagara? How did the English understand the Indigenous conception of shared hunting territory at this time? It is still unclear to me whether the English ever saw themselves as partners in the Dish. Did we see them this way?

The Dish with One Spoon might be referenced on the 1764 Niagara belt. There is a theory that those Dish-shaped hexagons on the belt are places the English intended to ‘polish the chain’ that binds us, to return to talk. The hexagons might be representations of significant British forts at the time, one being the house of Molly Brant and William Johnson. There was a commitment made at Niagara to continue talking, to remember past agreements on a regular basis, and for the Crown to protect its Indigenous allies against frauds and abuses on their lands.

As Canada picked up the crown, did it also keep hold of these promises of protection? Could I discuss the Covenant Chain and the 1764 Treaty of Niagara in the context of the train blockades of 2020? I watched a press conference about Wet’suwet’en solidarity actions by the Band Council Mohawk Chiefs, and they remembered the agreement at Niagara. They mentioned the 1764 belt right off the top.