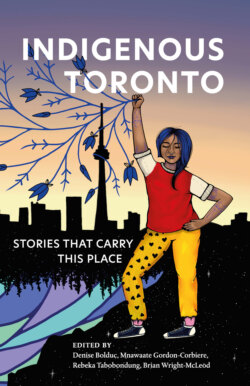

Читать книгу Indigenous Toronto - Группа авторов - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

REMEMBER LIKE WE DO

ОглавлениеANGE LOFT

The following essay includes excerpts from ‘Indigenous Context and Concepts,’ which was prepared for the Toronto Biennial of Art in 2019. This non-authoritative conceptual document was geared toward the curatorial staff and international artists’ cohort. Amidst overarching themes of collectivity and connectivity to the waterfront, I drafted a vision of the city through the lens of Indigenous alliances, governance, symbolism, and mnemonic devices.

I drew heavily on the research from the Talking Treaties project, an art-based research initiative to share and reflect Indigenous presence and knowledge in Toronto, initiated in 2015 with Jumblies Theatre and Arts. The excerpts are interrupted by ongoing thoughts, prompts for more research, and reflective activities from Talking Treaties’ forthcoming illustrated workbook, A Treaty Guide for Torontonians. Though certainly not exhaustive, these excerpts speak to the capacity of Indigenous ways of remembering in relating the agreements between our nations.

Authority around Toronto’s Indigenous narratives is a complex subject, as layered as the settlement history of the city. This was, historically, a place of bounty. It was a seasonal meeting place, a place for trade and ongoing council. It’s been a place where Indigenous Nations have come together to remember and relate going back thousands of years. Toronto did a lot of forgetting to become what it is today. All rivers were renamed, ‘requickened,’ first in French and then again in the English image. Maps were updated, stripping away thousands of years of land-based knowledge. Though the name ‘York’ tried, the Indigenous title ‘Toronto’ won.

There’s one theatre workshop I facilitate where I begin by placing a map and a small stuffed beaver on a table. It’s an old map, drafted by the French for this area, from the time period when the Seneca had Teiaiagon and Ganatsekwyagon. It will show the Carrying Place leading up to Lake Simcoe, where it says ‘Lac De Taronto.’ Why is the word Toronto based on a Mohawk word for a Wendat/Neutral fishing practice, taken from the time when there were predominantly Seneca settlements in the area? Go back to why the French marked those weirs on their maps, and to why the English sat right on top of those spots later. There was a lot to be gained here. We start there with access to beavers and the need for keeping up alliances.

Map of the Toronto Carrying Place, 1619–1793, C.W. Jefferys.‘Carte des Grands Lacs,’ 1680, Abbé Claude Bernou.

THE KNOT THAT BINDS US

To the Haudenosaunee, the term used for the Covenant Chain had a meaning associated with clasped arms. There is an arm gesture, which involved grasping the forearms, which was commonly used to mean binding friendship. To show this union at an early pact for peace on the St. Lawrence, a French priest described a Haudenosaunee diplomat who: Took hold of the Frenchman, placed his arms within his, and with his other arm, clasped that of the Algonquin, calling it the knot that binds us.1

The linkage between the Haudenosaunee and the English was originally described as hands bound together with rope. This metaphor changed over time, because the bond could break. The concept was strengthened, imagined as a chain cast in iron, but that chain would rust with time and was too common. The Covenant Chain was cast in silver. To prevent it from tarnishing, it would have to be polished. The rhetorical interpretation of the connection between them changed over time.

Canada, made up of two European nations, has some big commitments it is avoiding. Does the federal government remember the Indigenous alliances made with the French? The name carried on for the French representative is Onontio, Mohawk for ‘great mountain.’ Onontio promised to mediate quarrels and provide supplies, too. What about the agreements made with the English crown? Do they know about the roles the English took up from the Dutch?

CORLAER REQUICKENED

Chiefs were often namesakes of others, carrying forward the legacy of the previous line of name holders. The fifty Chiefs of the Haudenosaunee have each their own name and insignia upheld since their confederation. The continuity of title is related to the condoling and naming practice of Requickening. The title of Corlaer was the name of the original negotiator on the Dutch side of the Two Row Wampum agreement with the Mohawk in 1613. The name continued to be used by Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabe even after the English took New York and assumed the Dutch role in alliance. This act allows the name of the deceased to be passed on along to a successor, with the roles and responsibilities of the prior name holder.

Does Canada know the duties of the names it picked up along the way? Does anyone there have time to learn? Who are their knowledge keepers? We know that the power is going to change hands, and decision makers will forget, on both our side and on the federal government’s side. When we are in conflict with Canada, we are continually pointing to the symbols that bind us. We hold up our flags and adorn our bodies with reminders of our governance structures. In enacting unity between our nations and protecting each other, we show them that we remember our part of the story and that they are in the act of ignoring us.