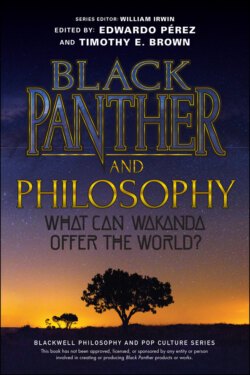

Читать книгу Black Panther and Philosophy - Группа авторов - Страница 24

3 Sins of the Fathers Historical Injustice and Its Repair in Black Panther

ОглавлениеBen Almassi

SON: Baba?

FATHER: Yes, my son?

SON: Tell me a story.

FATHER: Which one?

SON: The story of home.

FATHER: Millions of years ago, a meteorite made of vibranium, the strongest substance in the universe, struck the continent of Africa, affecting the plant life around it. And when the time of man came, five tribes settled on it and called it Wakanda.

Black Panther tells a story with history, and despite arriving in 2018 as the eighteenth film in the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU), this history is primarily its own, secondarily related to the real world, and only tangentially concerned with the wider events of the MCU.

The film’s rousing opening is a unifying creation myth every Wakandan child surely knows by heart. And Wakanda, as we first encounter it, seems like an ideal society – socially, technologically, aesthetically – triumphantly crowning its new king, T’Challa. For all its Afrofuturistic splendors, though, Wakanda’s history includes acts of injustice and wrongdoing that predate the story’s beginning and remain unresolved as the story begins. Such injustices include human trafficking in Nigeria where Nakia is undercover, appropriation of Wakandan and other African artifacts by the Museum of Great Britain, and the murder of T’Challa’s father, T’Chaka, during a terrorist attack in Captain America: Civil War.

Of course, the historical injustices really driving Black Panther are tragic deaths in 1991: the murder of W’Kabi’s parents and others by Ulysses Klaue while stealing vibranium from Wakanda, and then in Oakland, the fratricide of Wakandan prince N’Jobu by his brother T’Chaka. The first is an outrage which unites all of Wakanda in the aim of bringing Klaue to justice. The second is T’Chaka’s secret shame, which threatens to tear Wakanda apart.

Though he did not commit these wrongs, as king (and our hero) T’Challa holds himself responsible for their resolution, and so he must reckon with the conflicting responses to historical injustice of his father, his closest allies, and his cousin (and the film’s villain and tragic figure) N’Jadaka, a.k.a. Erik “Killmonger” Stevens.

Philosophy has its own rich history, one in which questions of justice figure prominently. What is the nature of justice? To whom is justice owed? What does justice require? Notice the ambiguity in this last question – are we concerned with what justice requires ideally, or what justice requires given that…?