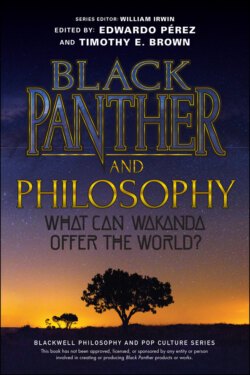

Читать книгу Black Panther and Philosophy - Группа авторов - Страница 31

Killmonger’s Imperialism and the Master’s Tools

ОглавлениеBlack Panther was a huge hit, with a $200 million opening weekend US box office on its way to staggering total grosses of $700 million domestically and $1.3 billion worldwide. And the hashtag that was trending on Twitter that spring? #KillmongerWasRight.

Killmonger wasn’t raised behind T’Chaka’s carefully constructed wall of ignorance. In many ways he knew more truth than anyone about Wakanda, about what it had done and what it could do to upend the world’s balance of power. Yet the danger of single-minded devotion to corrective justice as retribution is that it needs offenders to punish. Killmonger was able to give W’Kabi some level of satisfaction against Klaue, but what about his own claim of retribution against T’Chaka? The king who killed his brother and abandoned his nephew is gone, so who is left for Killmonger to serve justice to? “The world,” he answers, as the foundations of his claim to corrective justice erode and retribution becomes untethered from any legitimate or proportionate punishment. Killmonger’s vengeance is let loose.

Vengeance is not justice,15 but it’s not always easy to tell them apart. Perhaps no one knows this better than T’Challa, who emerges from the pain and loss of Civil War with this resolve. Having nearly killed Bucky Barnes, he tracks down the man truly responsible for his father’s death, Helmut Zemo, just as Zemo’s ultimate plan is nearly complete: he has turned Captain America and Iron Man against each other. “Vengeance has consumed you. It is consuming them. I am done letting it consume me.” T’Challa tells Zemo. “Justice will come soon enough.” It’s a hard-won lesson; if only he could share it with his long-lost cousin.

Deprived of his father and Wakandan community, N’Jadaka availed himself of the resources he did have and built himself into the mighty Killmonger we meet in the film. What resources? The Naval Academy, MIT, SEALs – “Killmonger is not a product of the ghetto,” Serwer explains, “so much as he is the product of the American military-industrial complex.”16 Many viewers see Killmonger as a damning depiction of Black American masculinity, for better or for worse. Indeed, the philosopher Christopher Lebron criticizes the film, saying that it “uplifts the African noble at the expense of the black American man.”17 Serwer sees that same tragic emptiness in Killmonger as Lebron does, but interprets this to the filmmakers’ credit rather than blame. “It renders a verdict on imperialism as a tool of black liberation,” Serwer argues, “to say that the master’s tools cannot dismantle the master’s house.”18

Whatever else is going on, that last phrase is definitely on point: against poet Audre Lorde’s warning, Killmonger is confident he can use the master’s tools to do just that. He says as much when he becomes king (“I know how colonizers think. So we’re gonna use their own strategy against’em”) and in response to T’Challa (“I learn from my enemies, beat them at their own game”) in their final confrontation. His actions show this too. Orchestrating regime change in Wakanda, he follows his training, disrupting existing leadership structures and destroying the cultivated crop of Heart-Shaped Herb. As Agent Ross says, “He’s one of ours.”