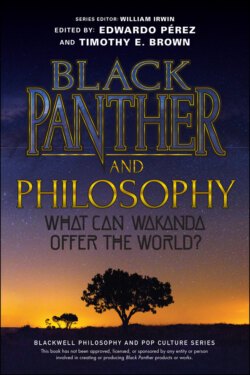

Читать книгу Black Panther and Philosophy - Группа авторов - Страница 25

“Every Breath You Take Is Mercy from Me.”

Оглавление“Ideal” needn’t assume perfection, because ideal theories of justice can recognize and account for human fallibility, selfishness, scarcity, and the like. Nevertheless, ideal theory in philosophy works by abstracting away from messy complicating contingencies to provide a generalized model of the phenomenon in question. “What distinguishes ideal theory,” the philosopher Charles Mills explains, “is the reliance on idealization to the exclusion, or at least marginalization, of the actual.”1

John Rawls’s (1921–2002) massively influential book A Theory of Justice is one such example, a careful, systematic account of what justice requires ideally speaking. Here Rawls attempts to identify “the principles that characterize a well-ordered society under favorable circumstances.”2 It’s not that non-ideal questions are unimportant, but Rawls thinks we must construct an ideal vision of what justice requires first. By stepping outside of real-world conditions, contemplating the fundamental principles of justice we’d all choose if we were ignorant of our personal (and so possibly biasing) circumstances, we might come to recognize what Rawls calls justice as fairness.3

The characters in Black Panther are not contemplating justice from behind a veil of ignorance, nor applying ideal principles of justice to govern a nascent Wakandan society. Rather, Nakia is working to prevent human trafficking and to disrupt its existing networks. T’Challa is not just ensuring Wakanda’s safety and its vibranium supply, he is working to make Klaue pay for past crimes. Killmonger is not just asserting his right of Wakandan citizenship, but avenging his father’s murder and his own abandonment. They all seek some form of Aristotle’s corrective justice,4 to restore the conditions of justice damaged or destroyed by wrongdoing. They are concerned not with justice in the abstract, but with justice in their world, a world steeped in history.

“Almost by definition,” Mills argues, “it follows from the focus of ideal theory that little or nothing will be said on actual historic oppression and its legacy in the present, or current ongoing oppression, though these may be gestured at in a vague or promissory way (as something to be dealt with later).”5 Ideal theory can be powerful, but it is necessarily incomplete. Ideally, we would never do one another wrong, so it’s not surprising if an ideal theory of justice offers scant advice on what should happen after we do. A complete theory must address the aftermath of injustice as itself a special context of action and evaluation. Among other things, it must treat the experience and perpetration of injustice as something to be reckoned with, not just avoided in the future. It also must recognize the pitfalls and other difficulties we face on the path from injustice back to justice – the challenges of getting there from here.