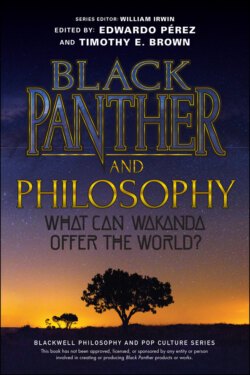

Читать книгу Black Panther and Philosophy - Группа авторов - Страница 29

“In Times of Crisis, the Wise Build Bridges.”

ОглавлениеDespite popular assumptions, reparative justice is not really about monetary payments for historical injustice; “the fundamental issue in reparations,” the philosopher Margaret Urban Walker writes, “is the moral vulnerability of victims of serious wrongs.”8 Sure, if you want to do right by me after, it matters how you hurt me – you’ve stolen my car, destroyed my garden, appropriated my culture’s artifacts to add to your museum collection. But for those who believe in reparative or restorative justice, “the harm done is only peripherally about ‘stuff.’ Instead, the harm is understood in the relational realm.”9

Thinking of it this way, reparative justice doesn’t ask us to look backwards, but to do what we can to repair our moral relationships and our communities that have been hurt by historical and ongoing injustices. Admitting and apologizing for our role in wrongdoing and making amends matter because they do the work of relational repair. The key to reparative justice is communication between those who commit injustice and those who are hurt by it. Amends aren’t charity or compensation for what’s been lost. They work because of the “expressive burden”10 they carry: their ability to convey my regret, my acknowledgement of wrongdoing, and most of all, my recognition of those I hurt as full members of our shared moral community, as deserving of respect and consideration as anyone else.

And yet relational repair is not always achievable. Some victims are unable to forgive; some perpetrators fail to acknowledge or even realize their wrongdoings, and among those who do, some cannot bring themselves to apologize or do what’s needed to make amends. There’s no real sense that the British recognize their appropriation of African artifacts as wrong, so until they do, is it reasonable to ask Wakandans or other Africans to begin working toward relational repair? Or recall the last exchange between a defeated Killmonger and a victorious T’Challa, who carries his wounded cousin into the fading evening light.11 “Maybe we can still heal you,” T’Challa offers; maybe reconciliation is still possible. But Killmonger refuses. His self-respect and dignity won’t allow him to accept the bondage of incarceration – and his colonizer’s mentality won’t allow him to imagine anything else.

Though we’ve considered restitution, retribution, and reparation one by one, these responses to historical and ongoing injustices aren’t mutually exclusive. People and institutions often react to injustice with a mixture of these – or we might find ourselves reacting to injustice in a way that doesn’t include any of them or that ignores the need for corrective justice altogether. In Black Panther, T’Chaka, Killmonger, and Nakia offer radically different visions for Wakanda after injustice, visions for our hero – and for us – to reckon with.