Читать книгу Stepan Bandera: The Life and Afterlife of a Ukrainian Fascist - Grzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe - Страница 10

Cult, Myth, Charisma, and Rituals

ОглавлениеThe cult of the leader is a phenomenon created by and rooted within a particular society, group, or community that is prepared to accept the ideological dimensions of the cult. A leader often emerges in a time of crisis and his adherents believe that he will help the community weather it. The power and charisma of the leader derives usually only in part from him. In greater measure, it is a social product, a creation of social expectations vested in him.[1] The leaders around whom personality cults are established are therefore either charismatic or, more frequently, believed to be charismatic. Charisma might be a “personality gift, a situational coincidence, or a particular pact between leader and the followers.”[2]

A charismatic leader cannot exist without a “charismatic community,” which would accept, admire, celebrate, and believe in his “extraordinary” qualities. To achieve this state of mind and affairs, an emotional relationship between the leader and the community must be established. The community feels connected with its leader who, as his followers believe, takes care of them and leads them toward a better future.[3] One of the most effective ways to establish an emotional relationship between the leader and the community is through the performance of rituals. The practicing of political rituals is crucial for the formation of a collective identity that unites a group. Rituals influence the morality and values of the individuals practicing them, and transform the emotional state of the group.[4]

In practice, the process of creating charisma around the leader might proceed in different ways, depending on the nature of the movement. Small movements in multiethnic states—such as the OUN or the Croatian Ustaša—would use methods different from those used by movements that took control of the state and established a regime, such as the Italian Fascists or the German National Socialists. Charisma may also be attributed to a leader after his death. A charismatic community might still be under the influence of its deceased leader and therefore continue to admire and commemorate him. Not only the body of the leader but also his personal objects, including his clothing, writing desk, or pen might become imbued with sacred meaning after his death. The members of the charismatic community might treat those objects as relics, the last remnants of their legendary leader and true hero.[5]

The cults of fascist and other totalitarian leaders emerged in Europe after the First World War. Their emergence was related to the disappearance of relevant monarchies and of the cults of emperors who had been regarded as the representatives of God on earth, and whose absence caused a void in the lives of many.[6] Several fascist movements regarded the Roman Catholic Church as an important institution to imitate because the head of the Church did not need his own charisma to appear charismatic.[7] Nazi Party Secretary Rudolf Hess wrote in a private letter in 1927: “The great popular leader is similar to the great founder of a religion: he must communicate to his listeners an apodictic faith. Only then can the mass of followers be led where they should be led. They will then also follow the leader if the setbacks are encountered; but only then, if they have communicated to them unconditional belief in the absolute rightness of their own people.”[8] The legal philosopher Julius Binder argued in 1929: “The Leader cannot be made, can in this sense not be selected. The Leader makes himself in that he comprehends the history of his people.”[9] The historian Emilio Gentile observed that the “charismatic leader is accepted as a guide by his followers, who obey him with veneration and devotion, because they consider that he has been invested with the task of realizing an idea of the mission; the leader is the living incarnation and mythical interpretation of his mission.”[10] In this sense, the leader as an incarnation of a mission, or as a charismatic personality, might acquire the qualities of a saint or messiah that correspond to the community’s needs.[11] Followers of a leader believe that he comes as “destiny from the inner essence of people,”[12] because he embodies the idea of the movement and personifies its politics. Roger Eatwell observed that the leader might help people to “understand complex events” and “come to terms with complexity through the image of a single person who is held to be special, but in some way accountable.”[13]

A fascist leader is expected to be an idealistic, dynamic, passionate, and revolutionary individual. He is the “bearer of a mission,” who tries to overthrow the status quo and has a very clear idea of his foes. His mission is understood as a revolutionary intervention. He frequently presents himself as a person who is ready to sacrifice his life and the lives of his followers for the idea of the movement. His transformation into a myth is almost inevitable, and he may become the prisoner of his own myth.[14]

The interwar period witnessed the rise of a range of different charismatic leaders and personality cults. A few leaders, such as Tomáš Masaryk in Czechoslovakia, were neither fascist nor authoritarian.[15] Some of them, like Józef Piłsudski in Poland were authoritarian, but not fascist, and could best be described as military.[16] The cults sprang up in different political, cultural, and social circumstances. The most famous European personality cults were established around Adolf Hitler in Germany, Benito Mussolini in Italy, and Josef Stalin in the Soviet Union. Other cults surrounded Francisco Franco in Spain, Antonio de Oliveira Salazar in Portugal, Ante Pavelić in Croatia, Corneliu Zelea Codreanu and Ion Antonescu in Romania, Miklós Horthy in Hungary, Engelbert Dollfuss and Kurt Schuschnigg in Austria, Andrej Hlinka and Jozef Tiso in Slovakia.[17]

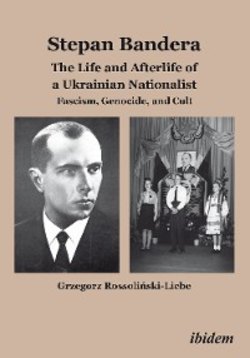

Unlike most of these personalities Bandera never ruled a state, nor was his cult institutionalized in a sovereign state during his lifetime. This changed, ironically enough, half a century after his death, when not only did his cult reappear in western Ukraine but the President, Iushchenko, designated him a Hero of Ukraine. Since the middle of the 1930s, Bandera has been worshiped by various groups, as Providnyk, as a national hero, and as a romantic revolutionary. The ideological nature of the Bandera cult did not differ substantially from that of other cults of nationalist, fascist, or other authoritarian leaders, but the circumstances in which the Bandera cult existed were specific. Moreover, the long period over which the Bandera cult has been cultivated is not typical of the majority of such European leader cults. Following his assassination, the Ukrainian diaspora commemorated Bandera, not only as the Providnyk but also as a martyr who died for Ukraine. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the cult re-emerged in Ukraine. One of the purposes of this study is to explain both the continuity of the Bandera cult, and its varieties.

The myth of a leader is related to the phenomenon of a leader cult but the two concepts are not synonymous. The leader myth is a story that reduces the personality and history of the leader to a restricted number of idealized features. It may be expressed by means of a hagiographic article, book, image, film, song, or other form of media. The myth usually depicts the leader as a national hero, a brave revolutionary, the father of a nation, or a martyr. It describes the leader in a selective way, designed to meet and confirm the expectations of the “charismatic” or “enchanted” community. Like every myth, it mobilizes emotions and immobilizes minds.

The leader myth belongs to the more modern species of political myths, embedded in a particular ideology. Such myths emerged alongside modern politics, in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. According to Christopher Flood, there is a reciprocal relationship between political myths and ideologies. Ideology provides myths with a framework of meaning, and myths are a means of visualizing and manifesting ideology.[18]

For the purposes of this study, ideology is characterized as a set of ideas of authoritative principles, which provide political and cultural orientation for groups that suffer from temporary cultural, social or political disorientation.[19] Ideology oversimplifies the complexity of the world, in order to make it an understandable and acceptable “reality.” It also deactivates critical and rational thought.[20] For Clifford Geertz, “it is a loss of orientation that most directly gives rise to ideological activity, an inability, for lack of usable models, to comprehend the universe of civic rights and responsibilities in which one finds oneself located.”[21] Ideologies are more persistent in societies that have strong needs for mobilization and legitimization, such as totalitarian states and fascist movements, than in those without such needs. Owing to their unifying, legitimizing, and mobilizing attributes, ideologies can also be understood as belief-systems that unite societies or groups, provide them with values, and inspire them to realize their political goals.[22]

The political myth of Stepan Bandera was initially embodied in the ideology of Ukrainian nationalism, which, in the 1920s, 1930s, and early 1940s, underwent a process of fascistization. This ideology produced a whole mythology, consisting of a set of various political myths, of which the Bandera myth was perhaps the most significant. Examples of other important political myths embedded in far-right Ukrainian nationalist ideology are the myth of the proclamation of Ukrainian statehood on 30 June 1941 in Lviv; military myths, including the myth of the tragic but heroic UPA; and the myths of other OUN members and UPA insurgents such as Ievhen Konovalets’, Roman Shukhevych, Vasyl’ Bilas, and Dmytro Danylyshyn. Finally, it should be added that the Bandera myth was an important component of Soviet ideology and the ideology of Polish nationalism, each of which evaluated Bandera very differently from the way the Ukrainian nationalist ideology defined him.